The Man With No Name grows a conscience in Clint Eastwood’s Oscar Winning Western

History is a funny old thing. Most of what we know is based on empirical evidence: the observation and documentation of patterns and behaviour by means of experimentation. Most of what we read is spotty at best. Since the major points in history are invariably documented by the victors, their accounts are naturally biased, motivated by vanity and the will to see their actions justified. No leader would set out to disparage their own actions, to vilify their own methods or motivations — it’s human nature. Whenever I see statues or portraits of past leaders or other noblemen, I always question the validity of their captured glory. They always strike me as cold or haughty, a celebration of privilege and power rather than of any honourable achievement. Just because a nation is victorious doesn’t make them or their objectives virtuous. Some of history’s most celebrated figures were glorified warmongers, and cries of democracy and freedom will never disguise the fact that conflict is nearly always a byproduct of greed and conceit.

Unforgiven — a movie that actor/director Clint Eastwood sat on for years while he grew ripe enough to fulfil William Munny’s wizened journey — is set during a curious period in American history, a time when civilisation had begun to tame the savage beasts of the Old West. Events occur between 1880 and 1881, two decades before Edwin S. Porter brought the Wild West to the silver screen with his 1903 silent short The Great Train Robbery. Shortly after, the real-life Wyatt Earp began hanging around Hollywood looking to cash-in on his legend, and why wouldn’t he? There was nothing spottier in the annals of history than the Old West, a time when the fastest guns were celebrated and mythologised, becoming the era’s answer to modern celebrities. Earp saw a chance to exploit the lore of gunslinger legend. He knew there was gold to be had in dem dare hills.

Such mythology fit the fantastical realms of Hollywood like a diamond-studded Smith and Wesson in a cowhide holster, the Western inevitably becoming the major defining genre of the American film industry. Pitting good vs evil, establishing familiar settings, conflicts and resolutions and utilising familiar plot lines and scenarios, it was the first to establish genre as a mainstream concept. Influential film critic André Bazin would use the Western film as an example while discussing the concept of genre during the 1950s, a term that became a significant part of film theory by the end of the following decade.

By that time, actor Clint Eastwood was already a veteran of the Western genre having appeared in eight by the end of the 1960s. Incredibly, the seemingly ageless actor was already 40 by the time he starred in 1969’s Paint Your Wagon, a bloated, big-budget musical western that critic Roger Ebert would describe as a movie that, ‘doesn’t inspire a review. It doesn’t even inspire a put-down. It just lies there in my mind — a big, heavy lump.’ The movie came as something of a shock to fans of Eastwood’s iconic run as Sergio Leone’s archetypal antihero ‘The Man With No Name’.

Did Pa used to kill folks?

Penny Munny

Leone’s grizzled protagonist was the antithesis of the traditional, white-garbed hero with inhumanly high moral standards, stepping into antihero territory at a time of socio-political upheaval in the United States, the Civil Rights Movement, punctuated by the infamous Watts riots, the closest thing to a civil war in almost a century. Post-World War Westerns of the 40s and 50s had already explored darker themes and flawed outlaw protagonists (this was The ‘Wild’ West after all) but Leone’s Spaghetti Westerns turned a corner, and by 1969 Sam Peckinpah’s ultra-violent revisionist western The Wild Bunch had truly muddied the waters, presenting us with a lawless land that played witness to the onscreen murder of women and children. It was a far cry from the simple delineations of Hollywood’s Golden Age.

This kind of moral ambiguity and genre anarchy is prevalent in Unforgiven, a movie that questions the mythologies of the Old West, presenting us with a character mired in personal regret for the unconscionable deeds he once committed. Munny, a tower of inner turmoil carved from granite, has also killed women and children, or, in his own words, ‘just about everything that walks or crawled at one time or another’, and for once Clint is paying the ethical toll.

It should come as no surprise that Unforgiven was dedicated to Leone along with Eastwood’s other mentor, director and long-time collaborator Don Siegel, but Unforgiven is also bathed in the sentiments of the classic western, blessed with the kind of widescreen compositions that capture vast, desolate plains and uninhabited landscapes. The film’s opening shot is one of exquisite mourning, a tired silhouette digging a grave beneath a sun-toasted sky. The melancholic ‘Claudia’s Theme’, composed by Eastwood himself along with Lennie Niehaus, hangs over the film like a quaint, inescapable eulogy. It’s worth noting that by 1992 the once-dominant Western had fallen almost into extinction.

When we first meet Will Munny he’s a broken-down hog farmer struggling to fend for his kids, a man mourning the passing of a wife who had once cured him of his wickedness. Munny’s half-buried past plays to the idea of mythology and historical inaccuracies, themes first broached when a cocky young chancer, the self-titled “Schofield Kid”, rides upon Munny’s seclusion and tries to coax him into a bounty-grab. The youngster pitches the assassination as retribution for the cutting-up of a woman, a story passed around like Chinese whispers with the kind of subtle humour that underpins David Peoples’ razor-sharp screenplay.

Munny’s cocksure visitor — the nephew of an old acquaintance who had painted Eastwood’s character as the ultimate purveyor of death — grossly exaggerates the woman’s injuries, as does Munny himself when relaying an already overblown story to former partner Ned Logan (Morgan Freeman) while attempting to cut him in on the deal. Having witnessed Munny flounder at the feet of a hog pen, the kid is understandably dubious of the man’s legend. There follows a wonderful scene in which Munny, having initially turned down the kid’s offer, dusts off his old pistol and attempts to shoot some cans. Having spent so long out of the game his aim is off, but his temper is quickly sparked as the sleeping beast briefly stirs with an impudent shotgun blast that sends the cans into orbit. It’s a beautiful analogy of a character who will reveal himself gradually and painfully, but also suddenly, shockingly.

Ned, you remember that drover I shot through the mouth and his teeth came out the back of his head? I think about him now and again. He didn’t do anything to deserve to get shot, at least nothin’ I could remember when I sobered up.

William Munny

Unforgiven does a masterful job of teasing the man Munny once was and whether he’ll revert to his old ways. Western novels existed long before the Western film, and Saul Rubinek’s travelling biographer W. W. Beauchamp, a man consumed by the romanticism of a bygone era, sets about mythologising whichever gun leads the path towards glorification. His journey begins at the side of a colourful character known as English Bob, an ageing gunslinger who toots the horn of British nobility like a circus huckster. Bob gloats with sophistication, goading a train of full-bloodied Americans into a wager, shooting pheasants out of the sky with a casualty that leaves his travelling scribe beaming. Bravado goes a long way in the embers of the Old West provided you can shoot straight.

Bob is also looking for a pay day at the expense of some overzealous cowboys who crossed the line with a saloon whore, the meekest of a uniquely independent rabble who defy their position as bottom feeders with an earnestness and sense of pride that was rarely portrayed by such characters. Particularly steely is Frances Fisher as Strawberry Alice, a red-headed spitfire who fights for justice where there isn’t any and protects her colleagues like a particularly feisty mother hen. Aware of the nation’s newfound civility, Bob strolls into the town of Big Whiskey with a whimsical sense of invincibility that sees him glibly stop for a shave. The majority of residents tremble at the thought of firing on another human being. Unfortunately for Bob, there’s a rather ugly surprise in store.

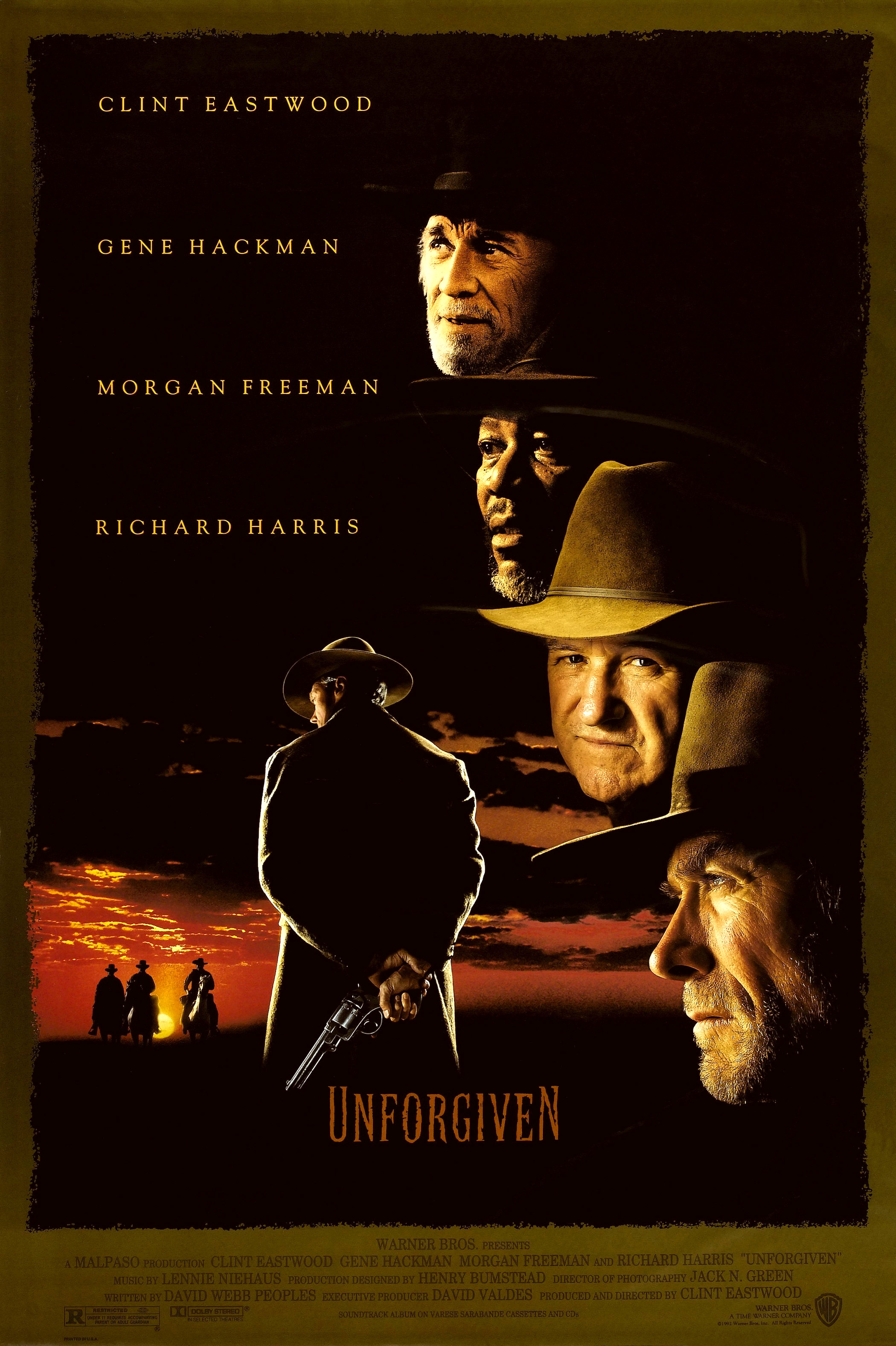

Bob is portrayed by Richard Harris, one of the many great actors who make-up Unforgiven‘s rich ensemble. In an era dominated by marquee action stars, Eastwood refuses to put himself front-and-centre, instead exploring a group of characters with an almost equal billing. It works — not only because of the astonishing array of talent on display, but because it allows Eastwood’s character time to brood, all cloak and shadows, inhabiting a grey area where feverish nightmares recall past incidents involving innocent men and shattered teeth. Munny claims to be a changed man as the memories continue to haunt what must be a very familiar journey. He refuses to drink, has no intention of taking sexual advances on his loot with the girls at the saloon. For all the self-aggrandising of English Bob and the borderline insufferable Schofield Kid, the latter claiming to have killed five men while flaunting himself as a coldblooded killer, Munny just wants to forget. He sees ‘outlaw legend’ for what it truly is.

Big Whiskey’s draconian sheriff, Little Bill Daggett (Gene Hackman), is another former gunslinger enamoured with the idea of his own legend. He wants to be remembered as a tough, honest-to-goodness lawman rather than a coldblooded killer, but the lines are tenuous. First impressions paint Daggett as the personification of America’s newfound civility. He’s (just barely) building his own house, where he romanticises about sitting on the porch and drinking coffee. Daggett once worked the big towns, the kind where serious trouble was but a whiskey hiccup away, but none of the townsfolk have experienced his reputation first-hand until the whores’ bounty attracts the attention of actual killers.

This inspires fear in the cowboys of Big Whiskey, not aggression or bravado. Peoples depicts these characters as real men with real feelings, and Bill is the elder statesman, the curmudgeon with the punitive paddle weaned on a bygone mentality. When we first meet Bill he’s actually rather forgiving, refusing to hang or even whip the cowboys who scarred-up Delilah (Anna Thomson), the purest, most traditional female character in the entire film. Bill lets them off with a fine, showing what appears to be humanity in the face of potential bloodshed, but it soon becomes clear that his mercy is more a product of disdain for the Saloon’s whores, a projection of fairness at the expense of the town’s lowest common denominator.

In reality, Bill is a colossal bully, another Wild West throwback shielded by a badge that he hides behind to fulfil a sadistic mean streak. His merciless beatings of a creaking Bob and a fever-ridden Will send a clear message to any would-be shooters looking to cash-in on the town’s recent injustice, but the beating-to-death of a captured Ned, moments after he washes his hands with the assassination, is less a controlled display of power, more an accident caused by ill-temper and overindulgence. Like Will, Daggett harbours a wolf’s instinct, the only difference being he still has a taste for raw flesh, has wound up in a place where feeding is easy and justifiable.

Well, I ain’t gonna hurt no woman. But I’m gonna hurt you. And not gentle like before, but bad!

Little Bill Daggett

The arrival of Beauchamp seems to awaken in Bill a long-dormant wickedness. First he embarrasses Bob in a jail cell, correcting Beauchamp’s account of the time he killed Corky “Two-Gun” Corcoran. Bob claims to have killed Corky for besmirching a helpless woman when in fact he’d shot him down in a cowardly act of drunken jealousy, yet another example of history rewriting itself. It’s here that Bill gets wrapped up in his own sense of romanticism, extolling the virtues of taking your time in a gun fight when all else is fevered madness; that’s the real key to a successful gunfighter, a philosophical titbit that will ultimately prove his undoing. The scene in which Bill leans on Ned’s shoulder, breathing his grisly fate into his ear, is nothing short of terrifying. Hackman is a revelation in this movie.

In Daggett, Beauchamp seems to have stumbled upon the real deal. Bill is fearless, schooled in the art of punishment and blinded by his own sense of self-esteem. During their jail cell stand-off, Bill isn’t quick to disparage his opponent’s skills, otherwise his show of masculinity will stand for nothing. He’s quick to call Bob a liar, a man of low character, but he refuses to peg him as a coward, and Bob is no coward, though his obvious fear of Bill when accosted in front of the townsfolk speaks volumes about exactly who we’re dealing with. Bill dishes out retribution with the backing of his deputies, always outnumbering his victims. He paints a fearsome picture, one partially for the benefit of his new biographer it seems, but he never walks into a gunfight on his lonesome. He revels in his role as judge, jury and executioner with a spittle-smeared indulgence that demands an audience. As far as he’s concerned, if anyone is worthy of a Wild West reputation it’s him, and in Beauchamp he seizes the chance to make history at the expense of anyone he deems worthy.

As for Will, that ruthless streak seems to have left him behind, even if it was his choice to pursue his past for the sake of children who’d surely be better off with him at home. Will is the kind of antihero so entrenched in wrongdoing that a devastating development is needed if we’re to forgive a sudden relapse. That development comes in the form of a murdered friend who had no place pursuing past deeds, a fact highlighted during a sobering scene when Ned realises he’s no longer a killer. During that scene, Will reluctantly takes over but finishes the job with devastating pragmatism, a subtle sign that his mask is finally slipping. Until that point, our trio of would-be-vigilantes have stumbled comically. The kid has long-since exposed himself as a virgin shooter with the kind of eyesight that could see a man take off his own foot. As for Munny, he can no longer mount a saddle without taking a header, something he attributes to his former wickedness towards animals. Not even a savage beating at the hands of Daggett can awaken his former demons it seems.

But then is happens. What begins as a touching scene painted in the grey watercolour of regret turns into a fateful forming of dark clouds. The so-called Schofield Kid has finally popped his cherry, proving Bill’s earlier claims to be true: it’s no easy thing to kill a man, something that forces the kid into early retirement. When a messenger rides out to meet them with the loot, the news of Ned’s death reaches Will and something inside of him snaps. Not only has his old friend been beaten to death, his corpse has been put on display as a warning to any future assassins. These aren’t the actions of a lawman, but of an outlaw with a taste for cruelty and dominance. News is, Will and the kid are next on Daggett’s list. Will finally takes a slug of whiskey, his transformation almost complete.

The climactic scene of Unforgiven is one of the great pay-offs in cinematic history. When Eastwood’s ‘Man With No Name’ re-emerges through the storm-battered Big Whiskey, not only are we rooting for the fabled monster inside, we’re willing him every step of the way. It takes a monumental heel to inspire such loyalty in a known murderer of women and children, and Hackman gives us a villain for the ages. When Munny enters the saloon, all hellfire and brimstone, Daggett is basking in the opulence of his misdeeds, laughing and promoting unity and justice as Ned, now another misconception of the Old West, lies rotting in assassin’s clothes in the ultimate ignominy. For Bill, it is yet another moral medal for his growing stature as ruthless nobleman. Tonight they drink, tomorrow they go in search of the devil. But with the killing of Ned, Bill crossed a line from which there is no coming back. He no longer has to seek out the devil. Death has come to Big Whiskey. The legend has become reality.

Deserve’s got nothin’ to do with it.

Will Munny

This is where the mythologies of yore suddenly become feasible. Bob’s wild tales have become the stuff of fiction, but art is about to imitate life. There is no romanticism to Will’s actions. He came for retribution and retribution is what he shall have. When the sound of Munny’s cocked shotgun plunges the saloon into silence, Munny is unconcerned by the odds facing him, or by the accusations of an indignant Bill after bar owner Skinny Dubois takes the barrel of a shotgun for putting his friend on display. Munny is no longer under any delusions about who he is. The clouds have parted and all that’s left is a treacherous sea of rage.

Once Dubois goes down and a misfire changes the odds, Will is calm and collected, picking off his opponents as panicked gunfire rains down among the chaos. He no longer has any hesitation when it comes to killing, it all comes so naturally to him, a fact punctuated when he casually executes a wounded foe while exiting the saloon. When Beauchamp attempts to come to terms with what he has witnessed, Munny is dismissive of the writer’s romanticism and Daggett’s claims that an experienced gunfighter will always go for the best shooter first. “I was lucky in the order,” he tells him. “But I’ve always been lucky when it comes to killin’ folks.” Moments later, a back-for-one-more-scare Bill further illustrates that notion following an incredible display of indignance that results in some of the finest dialogue the genre has to offer. The man is delusional to the dying end.

It’s a thrilling scene — the antithesis of the sweeping meadows and vast, open landscapes of the movie’s exterior shots, which have one foot in the Fordian epics of yore, but also capture a culture in transition, bidding farewell to a savage, untamed era as civilisation and all of its rules and boundaries close-in on all sides. The opening shot of the lonesome tree beneath a lush and peaceful sky, once again repeated at the movie’s end, seems to bid farewell to simpler times, Munny rumoured to have prospered in dry goods in San Francisco. Early in the movie, an isolated Munny mistakes The Schofield Kid for an assassin who has come to kill him for something he did in the old days, and there’s always a chance that another Bill Daggett awaits his arrival, that his legend has reached other plains.

Though 1990‘s Dances with Wolves can lay claim to inspiring the Western genre’s mainstream resurgence with its attentive observations and genre-free storytelling, it was Unforgiven’s post-modern twist that reinvigorated it for many. Eastwood’s Oscar-winning picture is less a sweeping epic, more an intimate tale told by some of the finest actors of a generation, one that unravels the myths of the Old West in favour of complex characters and personal conflict.

The trifecta of Eastwood, Hackman and Freeman makes you pine for the days when movies were not flawless commercial products micromanaged for immediate and perfect consumption. Unforgiven was a somewhat risky venture commercially, but also a platform for some of the industry’s finest. Visually, it is also something of a love letter from Eastwood, who, recalling his vast experiences with the genre, seems to yearn for a former love long-abandoned. With Unforgiven, he reacquaints himself with that love, and though the passing of time has altered many things, the magic remains.

Director: Clint Eastwood

Screenplay: David Webb Peoples

Music: Lennie Niehaus

Cinematography: Jack N. Green

Editing: Joel Cox