Proton packs, bachelor parties and wizened martial arts masters, VHS Revival brings you all the retro movie news from June 1984

June 1

In terms of 80s cult classics, June ’84 is a hard month to top, but gangster epics were also on the menu, and I don’t use the word Epic lightly. Sergio Leone’s almost mythical saga Once Upon a Time in America, edited down to a still-whopping 269 minutes for theatrical release on June 1, was taken from more than 10 hours of footage shot over 9 months. The film was chopped by a further 40 minutes for its Cannes Film Festival premiere and then by a further 90 minutes by American distributors Warner Brothers, who rearranged the film’s events into chronological order, making them incoherent and borderline unintelligible. Nobody has ever laid eyes on Leone’s complete version.

The story of a former Prohibition-era gangster who returns to the Lower East Side of Manhattan to confront the ghosts of his unconscionable past, the film is based on Harry Grey’s semi-autobiographical 1952 novel The Hoods and follows the rise of protagonist Noodles (Robert De Niro) from Jewish slum tough to notorious bootlegger and mafia boss. The brutal, often savage story of Noodles and gang members Patrick “Patsy” Goldberg , Phillip “Cockeye” Stein and little Dominic is told through flashbacks that were edited from the American theatrical cut entirely, laying waste to the intended version’s complex construction. The film, which boasts an incredible all-star cast that includes James Woods, Rusty Jacobs, Elizabeth McGovern, Joe Pesci, Burt Young and William Forsythe, also marks the feature-length debut of a young Jennifer Connelly.

Despite its titular promise, hardly any of Leone’s Italian-American production was filmed in the US, the majority of the movie shot in Rome at the world-famous Cinecittà Studios, with additional sequences filmed in Montreal, Paris, and St. Petersburg, Florida. With such a vast and temperamental cast, tensions flared in what would prove to be Leone’s last film owing to ill health. De Niro seriously contemplated turning down the role almost immediately after Leone urinated on his toilet seat after meeting the young star at his New York hotel suite, telling producer Arnon Milchan, “I can’t do the movie… Can’t you see that he pissed all over my toilet seat?”

What a diva!

Leone, who first approached De Niro about starring in the movie way back in 1973, wasn’t the only one to annoy fellow cast and crew members. James Woods became incredibly frustrated with De Niro’s intense style of method acting, describing the actor as something of a prima donna. “It’s just a bunch of old shit,” he would claim. “If it’s a great script and you’re working with good people, what’s the problem? I’m tired of the Actors Studio bullshit that has ruined movies for 40 years. All these guys running around pretending they’re turnips – they’re so fucking annoying. It’s 4 a.m. and you’re trying to get some shot done and they’re with a coach moaning about how they can’t feel this, can’t feel that. Just say the lines and get on with it!”

Leone, who first became interested in adapting the film’s source material as early as 1967, was also a notorious perfectionist renown for dragging out productions and exceeding budget, and Once Upon a Time in America was no exception, one scene on a crowded street shot a total of 36 times. The filmmaker would go above and beyond for a movie that he envisaged as his opus. As well as personally scouting for locations and overseeing rewrites, he would personally meet with over 3,000 actors between 1980 and 1982. So protracted were his plans that he even turned down the chance to direct The Godfather way back in 1972, a film that eventually went to Francis Ford Coppola.

Thanks in large part to distribution restraints, the movie flopped at the US box office with paltry returns of $5,500,000 on a budget of approximately $30,000,000. Though the stress and strain of such a mammoth production, and the many executive conflicts that ensued, no doubt contributed to Leoni’s dwindling health, his heartache over the film’s commercial and critical reception is believed to have been a factor in his downfall. Leone would die from a massive heart attack on April 30, 1989 in his native Rome. He was 60 years old.

Developed from a treatment by writer-producer Harve Bennett titled Return to Genesis, Star Trek III: The Search For Spock, devised only days after the release of 1982’s Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, was released in 2000 theatres across America on June 1 to the delight of Trekkies across the globe. The film was the first of two instalments directed by Dr. Spock, himself, Leonard Nimoy, something co-star and future Star Trek V: The Final Frontier director William Shatner was initially uncomfortable with owing to their long-time friendship. ‘Wrath of Khan’ director Nicholas Meyer was originally set to return but declined, later co-writing Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home (1986) and 1991’s Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country, a film he would also direct.

Starring a cast of veterans and newcomers in key roles, including the Oscar-nominated Dame Judith Anderson as Vulcan High Priestess T’Lar, Future Doc Brown Christopher Lloyd in an impressive dramatic role as Klingon Commander Kruge, and rookie Robin Curtis, who replaced future Cheers star Kirstie Alley in the role of Saavik, the movie picks up shortly after the events of its predecessor, undoing one of the most iconic moments in the series. ‘The Search For Spock’, which many consider to be the finest entry in the series, sees Admiral Kirk and his crew risking their careers on a quest to find Spock’s body. Spock, who famously died in Star Trek II, saving the Enterprise from certain destruction, was resurrected thanks to an altered ending that saw the character transfer his Katra (the Vulcan equivalent of a soul) to the body of an unconscious Dr. McCoy.

This unexpected cliffhanger displeased Meyer, who felt that Spock’s resurrection detracted from what many believe to be the finest scene in the entire series, which may explain his reluctance to continue on as director. Ironically, Nimoy was initially reluctant to continue on in the role of Spock beyond the second instalment, especially after a lukewarm reception for the first movie, which with a considerable budget yielded only moderate returns, but his experience working with Meyer saw the actor become even more involved as the sequels rolled on.

Nimoy, who cut his feature directorial teeth with ‘Star Trek III’, was less happy with his experience the next time around. “I did feel that I was being quite controlled, I guess is the word,” he would recall. “I was made to justify everything that I did and explain everything that I was doing, which took a lot of energy. And I resented it. It bothered me that I was being so carefully monitored because I really felt that I knew what I was doing. I thought the script was workable and did what it had to do, which was to find Spock and get him back on his feet. I thought it was an interesting idea, the whole idea of the Genesis planet evolving and Spock’s remains evolving with the planet. It may not have been as much fun a film as some would like, but I thought it did the job. It did it what it set out to do.”

Hoping to make a film that was “operatic in scope”, with characters who were more grounded and relatable, Nimoy would work with George Lucas’ Industrial Light and Magic, who produced the film’s impressive special effects, model work and live-action sequences. ILM, who despite working on ‘The Wrath of Khan’ were only approached after the film’s effects storyboards had been completed, were involved from the planning stages this time around, increasing their input in the film’s design and execution.

As Chicago Sun Times critic Roger Ebert would write, Nimoy’s grounded approach and ILM’s increased input would achieve a balance somewhere between the first two movies, “[The Search For Spock] is a good but not great Star Trek movie, a sort of compromise between the first two. The first film was a “Star Wars” road company that depended on special effects. The second movie, the best one so far, remembered what made the Star Trek TV series so special: not its special effects, not its space opera gimmicks, but its use of science fiction as a platform for programs about human nature and the limitations of intelligence. “Star Trek III” looks for a balance between the first two movies. It has some of the philosophizing and some of the space opera, and there is an extended special-effects scene on the exploding planet Genesis that’s the latest word in fistfights on the crumbling edges of fiery volcanoes.”

Faring marginally worse than its predecessor on an increased budget of $4,000,000, Star Trek III: The Search For Spock would manage a domestic box office gross of $76,471,046 and a worldwide gross of $87,000,000.

Walter Hill returned to the director’s chair with a film that proved something of a departure for a man who wasn’t exactly afraid of taking risks. Hill’s formidable 10-year run, beginning with 1975’s dazzling Charles Bronson-led debut Hard Times and ending with neo-noir rock musical Streets of Fire, would fizzle out with 1985’s mediocre screwball comedy Brewster’s Millions, a movie that Hill described as “an aberration in [his] career line”. Lauded for a diverse series of films that includes cult, splash-panel action thriller The Warriors, genre-reviving western The Long Riders and buddy-cop innovator 48 Hrs., Hill’s seventh picture was received rather poorly by critics for its misogynistic screenplay and lack of story, but has since been reappraised as a visceral classic and cyberpunk innovator.

Landing somewhere between The Warriors and Grease, Streets of Fire centres on the kidnapping of rock ‘n roll singer Ellen Aim (Diane Lane) and the efforts of ex-boyfriend and enigmatic mercenary Tom Cody’s attempts to rescue her from William Defoe’s villainous gang leader Raven Shaddock. The film also benefits from a rare, against-type turn from perennial wimp Rick Moranis as a sleazy band manager. Much like The Warriors before it, Hill’s abstract world, a thrilling siege of style and colour emboldened by an astonishing 80s soundtrack that includes former Fleetwood Mac vocalist Stevie Nix, The Fixx and Tom Petty, would also provide a platform for legendary songwriter Jim Steinman, who would pen “Tonight Is What It Means to Be Young” and “Nowhere Fast” specifically for the film. “[Hill] wanted to create his own “comic book movie,” without the source material actually being a comic book,” co-writer Larry Gross would recall. “And, from there, we started talking about Tom Cody.”

With Paramount eager to work with Hill following the success of 48 Hrs., he and Gross were determined to aim high, Tom Cruise and Daryl Hannah originally sought for the roles of Cody and Aim. “There was always the idea that we were going to discover a new Steve McQueen, you know? A young, white guy who would ride a motorcycle and have a carbine over his shoulder and be a mainstream icon,” Gross would continue. “And we saw them all. I mean we saw everyone. Eric Roberts. Tom Cruise. Patrick Swayze. Everyone, everyone, everyone, everyone. And we wanted Tom Cruise. But he got another job the day before we made him an offer. Our dream cast, who we met and we wanted, were Tom Cruise and Darryl Hannah. And we couldn’t pull the trigger on either deal in the right moment of time and we lost them.”

Rookie Michael Paré, who was eventually cast as Cody, was deeply unprepared for the ways of Hollywood, which led to onset conflict with comedian Moranis, who seemed to recognise the actor’s lack of savvy and set about exploiting it for his own amusement. It didn’t help matters that Moranis was one of producer Joel Silver’s dearest friends. “Rick Moranis drove me out of my mind,” he would lament. “There’s this whole wave of insult comedy. In the real world, if someone insults you a couple of times, you can smack them. Or punch them. You can’t do that on a movie set. And these comedians walk around, and they can say whatever they want. I’m just not that handy with that. Comedians are a special breed. They can antagonize you and say whatever they…want, and you can’t do anything to stop them…He’s this weird looking little guy who couldn’t get laid in a whore house with a fistful of fifties. He would imitate me. The first thing he says to me is “Do you just act cool, or are you really cool?” That was the first sentence out of his mouth to me in Joel Silver’s office. And I was like, “Oh…this is not going to go well.”

The film’s title was actually taken from a song written and recorded by Bruce Springsteen for his 1978 album Darkness on the Edge of Town, which seriously delayed a production that was later affected by adverse weather conditions. The song was initially scheduled to appear on the soundtrack until Springsteen pulled the plug, his main issue being that the track was set to be re-recorded featuring other vocalists.

Hill, who had always placed an emphasis on music, would struggle with the process of shooting to music, an element that was typically added in post-production. “This was tough stuff to shoot,” he would later recall. “I already had a great respect for people like [Liza] Minnelli. I just couldn’t seem to work it out without just putting up multiple cameras and shooting an awful lot of film… I later realized or talked to people about this and MGM in the old days everybody was on contract and they would rehearse for weeks. We don’t get that. We would stage it and shoot it. We got the songs a lot of times just a few days before we shoot.”

Despite Paramount’s enthusiasm, audiences didn’t take to Hill’s unique musical endeavour, the film managing disappointing domestic returns of $8,100,000, just over half of its $14,000,000 budget.

June 8

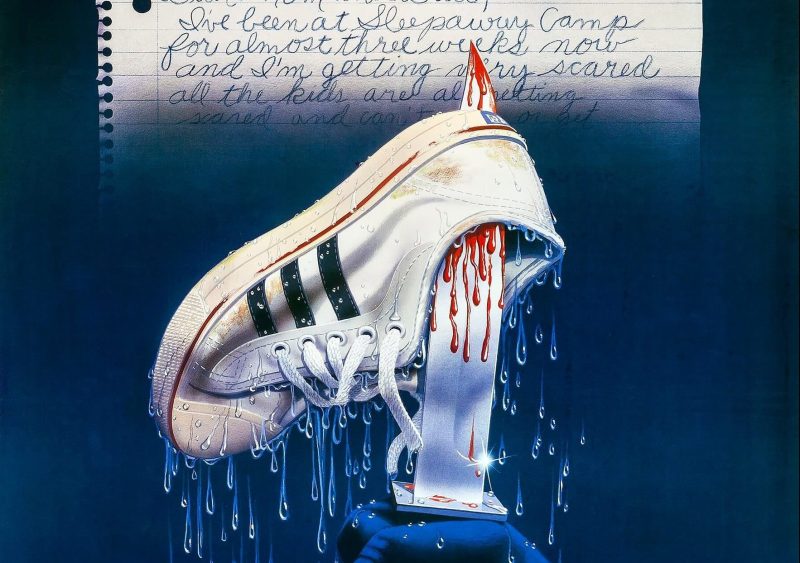

Breakdancing culture reached its mainstream apotheosis in 1984, though Stan Lathan’s American dance drama Beat Street was beaten to the dance by cult schlock purveyors Golan-Globus, who would rush rival film Breakin’ into production in their latest attempt to tap into popular trends. Afraid that hip-hop culture would be a short-lived phenomenon, Orion Pictures had also rushed their film into production, but Cannon Films went one better, purposely releasing their own pop culture derivative a month prior. They even made it to the Cannes Film Festival, where Beat Street was forced to share equal billing with not only Breakin’, but lesser-known efforts Body Rock and Prison Dancer. By the time Breakin’ was released, mainstream enthusiasm for breakdancing-based movies had already begun to wane.

Though Beat Street, largely owing to Cannon’s modern-day cult status, is now the least famous of the two films, it was certainly the more prestigious, setting events in the birthplace of the nation’s latest dance movement, New York City, while Cannon chose the relatively cost-effective Los Angeles. Songwriter and Civil Rights Movement advocate Harry Belafonte was also brought on as the film’s co-producer. Cannon’s unscrupulous tactics even led to the rushed-into-production sequel Breakin’ 2: Electric Boogaloo, initial Variety ads for the movie released before Beat Street had even hit theatres, further relegating the film to commercial antiquity.

Beat Street‘s story, which in many ways reflects the film’s commercial endeavours, revolves around aspiring South Bronx Disc Jockey Kenny Kirkland’s efforts to expose hip-hop music culture to the mainstream, something both films managed at a time when movies and music albums were becoming almost inseparable. In an era of ‘Dance Films’ that used pop-oriented soundtracks in a new and successful form of cross promotion, one that had landed Irene Cara an Academy Award for Best Original Song (“What a Feeling” from the film Flashdance), sales for both albums were much more even due largely to Atlantic utilizing a cluster release strategy for Beat Street’s singles, which flooded the airwaves long before the movie was set for release.

Headlined by future Commando actress Rae Dawn Chong, Beat Street, shot in The Bronx, Manhattan, Brooklyn and Queens, would take influence from the New York City-based graffiti documentary Style Wars released the previous year, several scenes staged inside the City’s subway system. Early hip-hop innovators Grandmaster Melle Mel & the Furious Five, Doug E. Fresh, Afrika Bambaataa, Soulsonic Force and the Treacherous Three, and Kool Moe Dee all performed or appeared in the film, which would manage healthy box office takings of $16,595,791. Cannon’s Breakin’ would almost double that with a domestic gross of $38,700,000 million on a budget of only $1,200,000. The fact that Beat Street was the more expensive production only added insult to injury.

On the subject of pop music cross-promotion, Ray Parker, Jr. would reach number one on the Billboard Hot 100 on August 11, 1984, thanks to the unmitigated success of Ivan Reitman’s offbeat, supernatural comedy Ghostbusters, the highest domestic box office earner of the year with a gross of $234,760,478. For those of you who thought Martin Brest’s innovative action comedy Beverly Hills Cop was the highest-grossing domestic film of 1984, it was, based on in-year releases. Ghostbusters was the highest-grossing based on what’s known as calendar gross. There’s a difference apparently.

Key to the movie’s power, asides from its potential from a peewee cultural marketing perspective (hands up who had a Ghostbusters lunch box), is its joyous propensity to deviate from the script and enter ad-lib territory, particularly with the ever-wonderful Bill Murray, who plays the part of cynical parapsychology professor Peter Venkman to the bone-dry hilt. After their research is dismissed and they’re fired from their jobs at Colombia University, Venkman, Ray Stanz (Dan Akyroyd in equally scintillating form) and Egon Spengler (Harold Ramis) set up a paranormal investigation and elimination service, which, at least initially, doesn’t attract much business. Who would have thought?

That’s until sexy singleton and professional cellist Dana Barrett (Sigourney Weaver) experiences some rather peculiar paranormal shenanigans and the whole of New York City comes under threat from shape-shifting god of destruction Gozer the Gozerian (talk about perfect business timing!). When Dana is possessed by evil demigod Zuul (there are few sexier than a possessed Weaver), it is up to our boys in beige and new recruit Winston Zeddemore to save the day, putting slimy green ghosts and even giant marshmallow men to the figurative sword with their trusty, and really rather dangerous, nuclear accelerator-powered proton packs. No wonder the Environmental Protection Agency was on their asses.

Ghostbusters was the brainchild of Aykroyd and was originally meant for himself and former Saturday Night Live co-star John Belushi until his premature death from combined drug intoxication on March 5, 1982 at the age of just 33. Original drafts, which were very much in the surreal SNL mode, featured protagonists who travelled through space and time to battle demonic and supernatural threats. The idea was put on hold due for financial reasons until Ramis came on board to help re-write the script and make affairs a tad more practical.

Elsewhere, practicality went out of the window. Backed by Columbia Pictures and a budget of approximately $30,000,000, Ghostbusters was the first comedy to indulge in expensive, high-tech special effects courtesy of Poltergeist‘s Richard Edlund. Edlund, who wasn’t exactly the studio’s first choice, was hired as the industry’s biggest players were otherwise engaged, including first choice Industrial Light & Magic, who were busy working on blockbuster sequels Return of the Jedi and Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. Edlund had recently left the company to start his own business Boss Films. Not a bad start for a company that would work on such fan favourites as Big Trouble in Little China, Die Hard and Cliffhanger.

Edlund initially struggled with the unprecedented task of making creatures that were simultaneously playful and terrifying. The creation of the iconic ‘Slimer’, which took six months to complete at a cost of approximately $300,000, was particularly tricky, not least because of relentless executive interference regarding the creature’s aesthetics. In the end, special effects artist Steve Johnson completed the design based on Aykroyd and Ramis’ wish to create some kind of visual homage to their late friend Belushi. The fact that Johnson admitted to consuming at least three grams of cocaine during the final stages of the design might be considered the ultimate homage to the fallen star.

With the likes of Ghostbusters and The Temple of Doom dominating the US box office during the summer months, Warner Brothers and Amblin entertainment, who lacked a vehicle to compete during blockbuster season, moved the release of Joe Dante’s alternative Christmas cracker Gremlins, originally scheduled for theatres in November, forward to June. It was a risk that paid off, the Spielberg-backed production grossing an incredible $212,900,000, which, while making it only the third highest-grossing domestic movie of 1984 (calendar gross that is), cost only $11,000,000 to make.

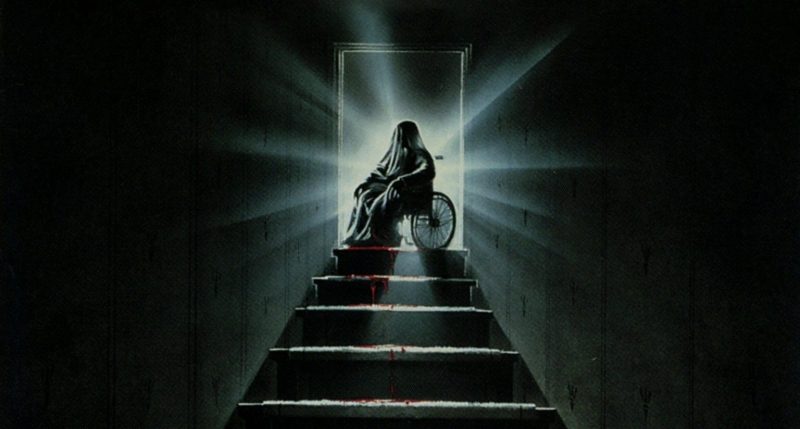

Dante’s deliciously dark homage to It’s a Wonderful Life caused something of a stir among parents groups for its seriously macabre content and anti-Christmas spirit, including an astonishing monologue during which Phoebe Cates’ American as apple pie princess Kate Beringer recalls the time when her father, impersonating Santa Claus for the silly season, slipped and broke his neck navigating the chimney. The movie, which sees an elderly woman shot through an upstairs window on a souped-up stairlift, also features a scene with a knife-wielding Mrs. Peltzer that wouldn’t look out of place in a slasher movie. Ironic since censorship hysteria, headlined by giallo’s morally bankrupt bastard child, reached its apotheosis that same year, festive slasher Silent Night, Deadly Night pulled from theatres shortly after its release in November ’84 for its murderous portrayal of jolly old St. Nick.

Initial drafts of the Gremlins script were actually much darker, treating audiences to the grisly decapitation of Mrs Peltzer and the eating of Billy’s pet pooch, Barney, who was instead hung from Christmas lights. “Steven was very instrumental because I was a young writer and I was like a kid in a candy store getting to work with Steven Spielberg, and he steered me into,” screenwriter Chris Columbus would later recall. “He said, ‘This needs to reach a wider audience.’ He goes, ‘What you’ve done could be great, but it’s an R-rated horror film. There’s a way that what you’ve written can reach a much wider audience.’ So we worked on several drafts of the script.” Along with The Temple of Doom, Gremlins contributed to the founding of the PG-13 rating, something else Spielberg was central to.

In pure Spielbergian fashion, Gremlins tells the story of a hopeless inventor who, struggling professionally, brings home a new family pet just in time for Christmas, a musical creature known as the mogwai. As cute and as harmless as the mogwai is, he comes with a few provisos, rules that must be abided by at all costs: 1) Don’t get them wet. 2) Don’t expose them to bright light, and 3) Don’t feed them after midnight. You see, mogwai multiply when they get wet, and the newly-named Gizmo’s offspring aren’t quite so adorable. Feed them after midnight and you’ve got serious problems.

Despite the usual moral naysayers, Gremlins was a huge hit with some critics. Roger Ebert, while showing a degree of concern for the film’s often vicious content, would praise the movie’s willingness to twist convention while staying true to the cinematic traditions of yore, writing, “The movie exploits every trick in the monster-movie book. We have scenes where monsters pop up in the foreground, and others where they stalk us in the background, and others when they drop into the frame and scare the Shinola out of everybody. And the movie itself turns nasty, especially in a scene involving a monster that gets slammed in a microwave oven, and another one where a wide-eyed teenage girl (Phoebe Cates) explains why she hates Christmas. Her story is in the great tradition of 1950s sick jokes, and as for the microwave scene, I had a queasy feeling that before long we’d be reading newspaper stories about kids who went home and tried the same thing with the family cat.”

Others were less enamoured. Leonard Maltin, who would later repeat his criticisms in meta-sequel Gremlins 2: The New Batch as an insider joke in one of the film’s many cameos, would lament the movie’s violence, dismissing Gremlins as “icky” and “gross”.

Audiences clearly had a different opinion. As Dante would recall in a 2017 interview with The Guardian: “At the preview, after the scene where one Gremlin explodes in a microwave, a mother watching with her kid came storming up and shouted at me that it was totally unsuitable for children. The Warner Brothers studio didn’t get it at all, didn’t think it was funny. But the picture became a phenomenon, one of the biggest of the year. It came out of nowhere. It was just one of those things you’re lucky to have once in your career.

June 22

In a delirious month for blockbusters, the summer’s true commercial champion, at least relatively speaking, came in the form of Rocky director John G. Avildsen’s low-key smash The Karate Kid, which on a budget of only $8,000,000, and without the creative and commercial powers of one Steven Spielberg, went on to gross a spectacular $130,400,000 dollars domestically, making a star out of a young Ralph Macchio and even landing former Happy Days comic relief Pat Morita an unexpected Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actor. The movie would only grow in popularity from there, becoming the top US rental of 1985 and winning the hearts of a generation.

Despite its hokey, child-friendly title and its connection to one of the decade’s biggest fads among young boys, The Karate Kid is the timeless tale of a fatherless teenager who finds solace in the teachings of a wizened karate master, a native Okinawan who not only learns him how to defend himself, but also how to find balance in all aspects of life. Faced with the anti-karate philosophies of troubled Vietnam Veteran John Kreese and his band of impressionable Cobra Kai bullies, Morita’s iconic and hugely endearing Mr Miyagi, a similar fish out of water, unleashes his long-dormant combat experience and all that it entails.

In reality, Morita was no stranger to difficult childhoods having spent almost a decade in a sanatorium after contracting tuberculosis at the tender age of two, a condition that left him encased in a body cast and unable to play with other children. At the age of eleven, Morita was sent to an internment camp along with 110,000 Americans of Japanese heritage following the conflict at Pearl Harbour. By the time he was a teenager, all he understood was life’s propensity to isolate, something that no doubt influenced what remains an absolutely spellbinding performance.

Thanks to Macchio’s newfound stardom among teenagers, The Karate Kid was quickly given the cultural marketing treatment with a quickfire sequel, a hit record, a best-selling videogame and a range of popular action figures, though the belated third instalment The Karate Kid Part III, released when Macchio was 28 and finally looking his age, proved a crane kick too far. Miyagi would star in one more sequel alongside future Oscar-winner Hilary Swank in 1994’s long-forgotten The Next Karate Kid, but by that time the magic was long gone… or was it?

In 2018, Macchio would star alongside former nemesis Johnny Lawrence (William Zabka) in the hugely popular series Cobra Kai, a nostalgic-heavy return to form that cleverly flipped the script by making former rich kid Johnny, a deadbeat now living in the shadow of an adult LaRusso’s success, as the sympathetic character. Now gearing up for its fourth series, Cobra Kai further solidified The Karate Kid‘s cult status, introducing the film’s fictional world, and the movies which preceded it, to a new generation of fans, each season reintroducing various characters from the original saga.

The only actor missing from Cobra Kai‘s formidable roster is the late Morita, though the show pays him due homage at every turn. On his working relationship with Morita, Macchio would recall, “It was truly the definition of magic when we did those scenes there was a give and take. It was like the perfect tango and without effort. It was effortless that’s the word. I didn’t know about how much richness it had I just knew it was easy to do so therein lies the truth for me. There was something otherworldly or whatever you want to call it.”

Let’s just call it Balance.

Box office powerhouse Sylvester Stallone experienced something of a blip in-between commercial juggernauts First Blood and Rambo: First Blood Part II, movies that raked-in a combined $425,600,000. While directorial debut Staying Alive (1983), the belated follow-up to Saturday Night Fever, did healthy numbers despite middling critical reviews, Stallone’s next acting role, a comedic deviation starring alongside country singing sensation Dolly Parton, bombed commercially, failing to break even with a paltry return of $21,000,000 on a budget of $28,000,000.

Creatively, Black Christmas director Bob Clark’s Rhinestone, an odd couple tale about a country music star who transforms Stallone’s obnoxious New York cabbie into a singer for the sake of a bet, didn’t fare much better, bagging an eyewatering nine Golden Raspberry Award nominations, including Worst Picture, Worst Screenplay, and, perhaps most ignominious of all, Worst Musical of Our First 25 Years. It would even bag two ‘Razzies’ for Worst Original Song and Worst Actor (Stallone himself). Stallone would turn down lead roles in Robert Zemeckis’ hit adventure comedy Romancing the Stone and Beverly Hills Cop to star in Rhinestone, which bagged him a $5,000,000 fee and a percentage of the film’s gross. Still, not the smartest move in hindsight.

Parton, who under fitness fanatic Stallone’s guidance completely change her dietary lifestyle while shooting the film, didn’t do quite as badly out of the whole ordeal, landing two top ten country hit singles in “Tennessee Homesick Blues” and “God Won’t Get You”. “Even though the movie did not do well and didn’t get good reviews, if you listen to the songs I wrote for it, they hold up,” she would later write. “I enjoyed writing that as much as anything I’ve ever done.”

The famously gregarious Parton, who would publicly defend Stallone’s culpability for the film’s lack of success, was certainly a hit with her muscular co-star, who spoke of the musician-come-actress in glowing terms. “The most fun I ever had on a movie was with Dolly Parton on Rhinestone,” he would say. “I must tell everyone right now that originally the director was supposed to be Mike Nichols, that was the intention and it was supposed to be shot in New York, down and dirty with Dolly and I with gutsy mannerisms performed like two antagonists brought together by fate. I wanted the music at that time to be written by people who would give it sort of a bizarre edge. Believe it or not, I contacted Whitesnake’s management and they were ready to write some very interesting songs alongside Dolly’s. But, I was asked to come down to Fox and out steps the director, Bob Clark. Bob is a nice guy, but the film went in a direction that literally shattered my internal corn meter into smithereens. I would have done many things differently. I certainly would’ve steered clear of comedy unless it was dark, Belgian chocolate dark. Silly comedy didn’t work for me. I mean, would anybody pay to see John Wayne in a whimsical farce? Not likely. I would stay more true to who I am and what the audience would prefer rather than trying to stretch out and waste a lot of time and people’s patience.”

Put succinctly, it was a bit of a mess.

In 1982, creative trio Zucker/Abrahams/Zucker, fresh off the back of hit spoof movie Airplane!, approached the ABC network with a novel idea. In tow was former straight actor-come-deadpan-revelation Leslie Nielsen, the potential star of a TV show that would become known as Police Squad!, which followed the eternally confused employees of a woefully inept law enforcement precinct. That show would one day evolve into the gloriously puerile Naked Gun Trilogy, but audiences weren’t quite ready for an offbeat show free from canned laughter cues, Police Squad! cancelled after just 6 episodes.

Police Squad! would garner something of a cult following during copious re-runs on US television, but with the show’s cinematic incarnation more than a half-decade away, Zucker/Abrahams/Zucker kept their inimitable formula alive with several lesser known spoof vehicles, including the 1984 spoof action comedy Top Secret!, which parodied everything from camp Elvis Presley musicals to classic Cold War spy films. As you may have come to expect from Zucker/Abrahams/Zucker productions, the film’s surreal action makes the plot somewhat peripheral. Let’s just say it involves a rock and roll singer, a resistance plot in East Germany and some of the most absurd visual gags of the era.

Taking Nielsen’s place as the film’s star was a young Val Kilmer, who actually performed the movie’s musical numbers himself, songs which were later released under character name Nick Rivers on the film’s soundtrack. Kilmer, who was dating singing sensation Cher at the time of filming, was a huge fan of Zucker/Abrahams/Zucker, and was delighted to work on their latest project in what was his first feature-length appearance. “I was a huge, huge fan,” Kilmer would recall. “I saw their theater in Pico [Kentucky Fried Theater] about 50 times. Once my kind father even rented the entire show for a party full of classmates, so I really knew their stuff.”

Kilmer is a revelation as the film’s lead, adapting surprisingly well to a still relatively new and difficult-to-grasp style of humour, something that his enthusiasm, commitment and willingness to learn certainly helped with. These were traits that would endear the youngster, who was still only 22 at the time of filming, to the writer/director trio. “I think Val was great in the movie,” Jerry Zucker would say, “and we were lucky to have found him because we read a lot of actors who gave it their all, but it just wasn’t quite happening.”

Jim Abrahams was also impressed with what Kilmer brought to the table, explaining, “[Val] seemed like a nice young kid who was absolutely devoted to the role. When most people come in to audition for a part, they kind of prepare the line and get an idea of the character and stuff like that. But Val actually came in to read for the role, he had prepared some Elvis song and sang it like Elvis with all of those moves. He gave the character and the part a lot of thought and work even before he came in to audition.”

Cut from approximately two hours to 90 minutes, Top Secret! was initially scheduled for release on the 8th of June, but the daunting prospect of going head-to-head with the likes of Ghostbusters and Gremlins saw the date moved to June 22. Despite their efforts, the unexpected cultural impact of The Karate Kid meant that the movie bombed anyway, at least in the minds of Paramount Pictures, who initially had high hopes for Top Secret!. Rumours that the film was actually pushed back because executives were disappointed with the final cut have never been confirmed.

Top Secret! managed a US domestic return of $20,500,000 on a budget of approximately $8,500,000.

June 29

For many young moviegoers the pinnacle of the sex comedy sub-genre, Neal Israel’s cult box office hit Bachelor Party, Tom Hank’ second breakthrough role in the space of a year along with Ron Howard’s fantasy romcom Splash, cemented the actor as one of the brightest comedic prospects of the era. So synonymous with the genre would Hanks become during the 1980s that his career was touted as being over as early as 1990 after the actor attempted to reinvent himself in Brian De Palma’s woeful Tom Wolfe adaptation The Bonfire of the Vanities. Hanks, who was seriously miscast as New York City pawn and Wall Street WASP Sherman McCoy, was later snubbed by Nintendo chiefs after the actor showed interest in the equally maligned Super Mario Bros: The Movie, feeling that his career had run out of steam. Boy, are their faces red!

Conceived off the back of commercial homerun Police Academy at a real-life bachelor party attended by producers Ron Moler and Bob Israel, as well as many of the the film’s original cast, Bachelor Party tells the story of… well, a bachelor party, namely party animal Rick Gassko (Hanks), a Catholic-school bus driver who decides to settle down and marry main squeeze Debbie Thompson (Tawny Kitaen). Shocked by his sudden desire to abandon the party life, Rick’s friends decide to throw the party of a lifetime, and I don’t say that lightly.

Rick promises to remain faithful, but like most bawdy teen comedies of the era, the stifling stench of conservatism threatens to ruin everything. Displeased that their daughter is engaged to an uncouth commoner, Debbie’s affluent parents set out to ruin her plans by having former boyfriend Cole Whittier (Robert Prescott) sabotage her relationship with Rick and attempt to win her back.

Top Gun‘s Kelly McGillis and Paul Reiser (Aliens) were both tied to the movie early into production but ditched due to a lack of chemistry. McGillis was also considered too unsexy for the role of Debbie at a time when female objectification in the mainstream had reached an all-time high. “Penthouse” Pet of the Month, Monique Gabrielle, who would appear fully nude in the film as Rick seductress Tracey, would enjoy a brief spell as a cult B-movie star before settling into a career as a porn star-come-producer. Let’s just say she fits right in.

Released during the sub-genre’s mostly woeful period of oversaturation, Bachelor Party was held in relatively high esteem by some critics thanks mostly to Hanks’ prodigious talents. The film also featured future Cannon favourite Michael Dudikoff as Ryko, a role that was turned down by original casting choice Ted McGinley due to prior commitments on another teen comedy favourite Revenge of the Nerds.

In his review for the Chicago Sun Times, Roger Ebert would write, “Is “Bachelor Party” a great movie? No. Why do I give it three stars? Because it honors the tradition of a reliable movie genre, because it tries hard, and because when it is funny, it is very funny. It is relatively easy to make a comedy that is totally devoid of humor, but not all that easy to make a movie containing some genuine laughs. “Bachelor Party” has some great moments and qualifies as a raunchy, scummy, grungy Blotto Bluto memorial.”

With Gen X teenagers flocking to cinemas in their droves, Bachelor Party did favourable numbers for such a low-risk production, distributor 20th Century Fox boasting returns of $38,400,000 on a budget of only $7,000,000.

Burt Reynolds returned to the wacky world of illegal cross-country racing in Hal Needham’s much anticipated but poorly received comedy sequel Cannonball Run II on June 29, a movie described by Roger Ebert as “one of the laziest insults to the intelligence of moviegoers that I can remember.” At the Movies co-host Gene Siskel was just as damning, calling the film “a total ripoff, a deceptive film – that gives movies a bad name.” Ouch!

In a trend that was reflective of the film’s content rather than the hype that preceded it, Cannonball Run II opened strongly, with a top ten opening weekend gross of $8,300,000. In the wake of a series of bad reviews, the film’s momentum sputtered to a crawl, however, becoming only the 32nd most popular film of 1984 in the US and Canada, with a total gross of $56,300,000 on a budget of approximately $22,000,000.

The film’s plot centres on Sheik Abdul ben Falafel’s attempts to win over his father after failing to write the Falafel name (really?) into the history books having lost the previous movie’s race. Though the film’s gimmicky roster of stars weren’t enough to save it from creative ignominy, Cannonball Run II is notable for being legendary crooner Frank Sinatra’s final silver screen appearance, the actor starring alongside fellow Rat Pack buddies Dean Martin, Sammy Davis Jr. and honorary member Shirley MacLaine, who all lived a notoriously wild lifestyle during the 60s and 70s. The movie would also feature a young Jackie Chan in only his third Hollywood role.

Sinatra, who appeared in what was little more than a cameo, caused quite the commotion when arriving on set, many of the cast and crew rushing to see the Rat Pack members reunited. Despite appearing in only two sequences, Sinatra, who was still one of the biggest stars in the world, received second top billing after Reynolds in what was something of an unprecedented move. The late Sir Roger Moore, who would famously parody the James Bond character in the original Cannonball Run just prior to the release of For Your Eyes Only, would decline the chance to return for the sequel as he geared up for his final appearance as 007 in the much maligned A View to a Kill. A then 57-year-old Roger, who had been criticised for outstaying his welcome as Bond, felt he could take the role of Seymour Goldfarb no further. How ironic!

Reynolds, famous for other car and stunt movies such as The Longest Yard, Gator, Smokey and the Bandit, Hooper, Stroker Ace, The Dukes of Hazzard and Driven, would say of his fascination with daredevil risks and automobiles, “One of the things that few people realize is that cars all have unique personalities; I know your readers understand that. The Oldsmobile Anniversary Edition we had made up for W.W. was as critical to that film as was the General Lee in Dukes, but neither one could have played the part of the Bandit car, and it could not have worked in Driven. Why did I get “enticed” to do the parts? Probably more due to my background in stunts on the pictures you mentioned–in The Longest Yard, the Maserati [a Citroën SM with a Maserati engine] was only a minor role, but a great car. I chose that picture because I had played halfback for FSU, and wanted to get paid to play football. Chase scenes are a good addition to any picture, whether it’s the speedboats in Gator or the chariot in Hooper, and I always had fun doing them, so that’s what it’s really about–the fun!”

Months prior to his star-making turn in James Cameron’s influential sci-fi classic The Terminator, Arnold Schwarzenegger would once again put his Teutonic accent to use in Richard Fleischer’s swords and sorcery epic Conan the Destroyer, released in theatres across America on June 29. The sequel to the surprisingly well-received Conan the Barbarian, the film would co-star fellow 80s icon and future Bond villain Grace Jones as muscular bandit warrior Zula, who, indebted to Conan, offers to join his quest to escort Queen Taramis of Shadizar’s virginal niece, Princess Jehnna, who is destined to restore the jewelled horn of the dreaming god Dagoth.

Eventual director Fleischer was suggested to producer Raffaella De Laurentiis by father and famous Italian producer Dino De Laurentiis after original choice and Conan the Barbarian director John Milius declared himself unavailable. Fleischer, who had already made the 1961 religious epic Barabbas and 1975’s American historical drama Mandingo, a movie described by Quentin Tarantino as a, “full-on, gigantic, big-budget exploitation movie, was only to happy to accept the role.” Interestingly, the term “Mandingo fighting” was later used in Tarantino’s revisionist western Django Unchained.

Ditching the darker tone of the original movie in an attempt to replicate E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial‘s phenomenal box office success, Universal demanded that Conan the Destroyer adopt a more family-friendly tone against the wishes of both Fleischer and marquee star Schwarzenegger, who was busy establishing himself as an intimidating commercial presence in fictional terms. Though the film, described by Roger Ebert as “sillier, funnier, and more entertaining” than its predecessor, received mostly positive reviews, American audiences were less enamoured with the sudden tonal shift, a fact that was reflected at the box office. Schwarzenegger and Dino De Laurentiis immediately ditched the series as a result.

Jones, who was an unprecedented physical specimen in the Schwarzenegger mode, was typically committed to the role of Zula, undergoing intensive combat training over a period of 18 months, though that didn’t stop her from becoming just a little over-zealous, the star putting two stuntmen in hospital after an accident involving a fighting stick. She also did approximately 90 percent of her own stunts. By all accounts, Jones was one tough son of a bitch.

Notorious workaholic Arnie was just as committed to the cause, his loyalty to Conan the Destroyer impacting The Terminator‘s own production schedule. Ultimately, this turned out to be a blessing. Not only did the delay allow Cameron to redraft and improve initial drafts of the film’s script, he was able to pen blockbuster sci-fi sequel Aliens, a film that was also stuck in production hell following several changes in management over at 20th Century Fox. Originally brought on as screenwriter only, Cameron would also land the director’s role for Aliens based on the success of The Terminator. The fact that Cameron and Arnie returned for Terminator 2: Judgement Day, a film that capitulated them to new levels of superstardom, only adds to Conan the Destroyer‘s importance to both of their careers.

Despite turning his back on the franchise, Arnie has often professed a desire to return to the Conan role, and almost did for the long-mooted The Legend of Conan, a project that was ultimately abandoned by Universal Pictures. “I was hoping to do another [Conan film], and I was hoping that the idea of Conan having been King for a long time and then just [throwing] it all away and [going] into retirement, off into the mountains…” the actor would reveal in a 2015 interview. “That whole idea always appealed to me. Then of course he gets asked back, because of some hideous and unbelievable things that happen in the kingdom.”

According to Arnie, The Legend of Conan is still on the cards pending re-writes.

He told you he’d be back.