Burning skyscrapers, horror icons and 80s robots, VHS Revival brings you all the retro movie news from July ’88

July 6

In a decade crammed with Brat Pack teen comedies, Greg Beeman’s License to Drive was somewhat late to the party, and watching it you certainly feel the fatigue of oversaturation.

Thanks in large part to the films of John Hughes, the 80s were awash with growing pains dramas that would one day become nostalgic pillows for a generation. Movies such as The Breakfast Club, Pretty In Pink and Weird Science tapped into teen alienation through a pop video lens as the MTV revolution caught fire. Such a formula proved key to countless childhoods, Hughes speaking the language of teenagers in a way that was rarely inauthentic or condescending.

License to Drive is still a fair ride, a similar staple for thirtysomethings high on nostalgia for all things 80s. The story of a smitten teenager who decides to cruise the city in his grandfather’s prized 1972 Cadillac Sedan de Ville despite failing his driving test, the movie speaks to the heady allure of adolescent romance and the thrill of teenage rebellion as the responsibilities of adulthood begin to emerge. Reuniting Corey Feldman and Corey Haim of The Lost Boys fame, License to Drive co-stars the impossibly beautiful Heather Graham as the aptly named Mercedes, who, much like Alicia Silverstone’s clueless Beverly Hills socialite Cher Horowitz in the 90s, would send teenage hormones racing across America.

Feldman, who once again played second fiddle as best bud Dean, has since admitted to being devastated when Haim, his real-life best friend and fierce rival, beat him to the lead role of Les Anderson. This was the fourth time Feldman had been ousted following similar casting experiences in Murphy’s Romance, Lucas, and The Lost Boys.

Feldman’s 2020 documentary Truth: The Rape of Two Coreys, a film about exploitation and abuse in Hollywood, largely focuses on the pair’s time shooting License to Drive, an experience that directly contributed to Haim’s tragic drug addiction and subsequent death at the age of just 38.

As suspected, a movie about driving, girls, booze and the perils of being grounded ticked all the right commercial boxes in 1988, a fact proven by the film’s domestic box office gross of $22,433,275, a tidy sum for a production which cost somewhere in the region of $8,000,000.

In an era of severe sequelitis, robotics comedy sequel Short Circuit 2 was also released on July 6, a movie that Vincent Canby of The New York Times was particularly unimpressed with, writing, “For anyone over the age of 6, [Short Circuit 2] is as much fun as wearing wet sneakers”, and it’s difficult to argue, director Kenneth Johnson delivering an unbearably mawkish outing which expands on a story that quite frankly didn’t need expanding on.

Regardless of Canby’s scathing assertion, children under the age of 6 (and probably some who were a tad older) would have lapped up the continued adventures of Johnny Five at a time when Nintendo’s Robotic Operating Buddy, R.O.B., found itself in millions of homes across America, and to a lesser extent Europe. With his vaguely human characteristics, puerile wisecracks and a plethora of pop culture references, cinema’s most energetic technological fancy was quite the draw for audiences unconcerned with predictable screenplays and studio money-grabs, though I do remember being deeply underwhelmed by Short Circuit 2, one of my first lessons in the horrors of anticlimax.

This time our mechanical scamp is manipulated by a gang of criminals who wouldn’t last five minutes in New York City’s real underworld, a fact punctuated by their plan to utilise a highly conspicuous, smart-alecky robot for a high-profile jewel heist. I’m sure it’ll all go swimmingly.

Surprisingly, the Short Circuit films were never given the modern reboot treatment, though it did come close, actor Fisher Stevens even showing an interest in reuniting with old buddy ED, though the project never made it past the development stage. Rumours are that the proposed remake was much darker in tone. That wouldn’t have been difficult.

The figures were a fair reflection of the movie’s shortcomings, Short Circuit 2 managing a US domestic gross of $21,630,088 — disappointing numbers for a high-concept movie with a budget of approximately $15,000,000. Producers were initially keen on rehiring Steve Guttenberg as Newton Crosby from the first movie, though the actor declined, later admitting that he regretted turning down the role after his mainstream stock plummeted.

Still a bullet dodged as far as I’m concerned.

July 8

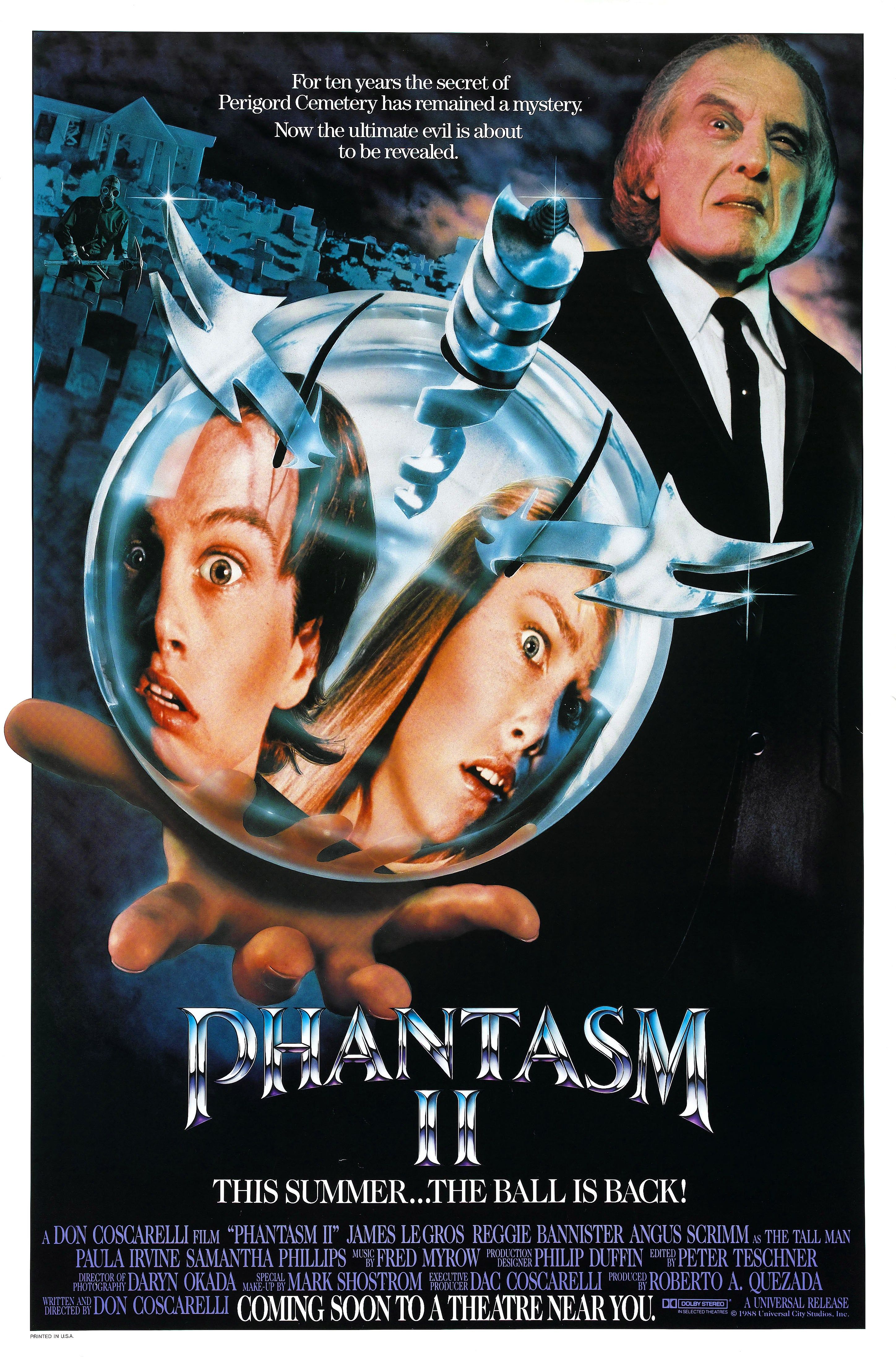

July 8 would see the emergence of an unlikely sequel almost a decade in the making in Don Coscarelli’s action horror Phantasm II. Released way back in 1979, the original Phantasm was something of a head scramble, a barmy slice of hokum which plays out like a wild fever dream that has garnered a huge cult following in the decades since its release.

Phantasm II would also mark the return of one of horror’s most overlooked icons in Angus Scrimm’s gaunt and distinctly treacherous ‘tall man’, a lurching ogre who once again leads a gang of bizarre minions through a plot of nonsensical treachery, utilising some rather nifty killer spheres that careen through the hallways of the infamous Morningside Cemetery, embedding themselves in the skulls of unsuspecting victims and drilling for brains the way barons drill for oil.

This time protagonist Mike, unforgivably recast, is released from a mental asylum and immediately looks to put an end to the evil misdeeds of his nemesis in a sequel that incorporates a buddy element and is bigger, louder and gorier than its predecessor, taking its cue from popular action sequels of the era.

Initially reluctant to make a sequel to a movie that he regarded as being conclusive, writer-director Coscarelli eventually bowed to pressure and was rewarded with a $3,000,000 budget by Universal Studios, a former horror giant who desperately wanted a franchise on their roster, and who ultimately took creative control of the project, rejecting the kind of ethereal ambiguities that made the original so unique. Greg Nicotero and Robert Kurtzman, who would later join the wizards over at K.N.B. EFX (From Dusk Til Dawn), were put in charge of the film’s practical effects.

Phantasm II did reasonable numbers for such an obscure sequel, more than doubling its outlay with a US gross of $7,282,851, which speaks to the movie’s dedicated cult following. The series would spawn two more direct-to-video sequels, as well as a fifth movie as late as 2016, the latter even managing a small theatrical release. I imagine it’s quite the journey.

Dudley Moore and Liza Minnelli would reprise their roles as Arthur and Linda Marolla Bach in comedy sequel Arthur 2: On the Rocks on July 9, though the two probably wished they hadn’t, particularly the Emmy, Grammy, Oscar, and Tony Award-winning Minnelli, who would earn the title of “Worst Actress” at the 1988 Golden Raspberries.

The follow-up to 1981‘s Oscar-winning Arthur, the tale of a billionaire alcoholic who falls for a working class girl from Queens, New York, while on the cusp of an arranged marriage to a wealthy heiress, the film co-stars Kathy Bates and features a returning Burt Bacharach, who would compose the Oscar-winning Best Original Song “Arthur’s Theme (Best That You Can Do)” for the original movie, a wistful track performed by 80s pop star Christopher Cross.

In the sequel, Arthur and Linda are desperate to adopt a child, though their plans are plunged into jeopardy when the jilted heiress’ father seizes Arthur’s inheritance, leaving him broke, jobless and facing sobriety.

The Washington Post’s Rita Kempley would criticise Arthur 2: On the Rocks for being, “…about as funny as the plight of an alcoholic,” adding, “It’s not a sequel, it’s a relapse.” Thanks in no small part to the release of Robert Zemeckis’ innovative and hugely successful live-action/animated comedy Who Framed Roger Rabbit? the previous month, Arthur 2 fared equally miserably commercially, managing a domestic box office of £14,700,000, which, compared with the original film’s unbridled success ($95,500,000), was considered a monumental disappointment.

The Arthur character famously began to encroach on Moore’s real-life persona, a series of falls, outbursts, domestic upsets and car crashes leading to unwanted press coverage that accused the actor of real-life alcoholism. In reality, Moore was suffering from the onset of Progressive Supranuclear Palsy, a rare neurological disorder related to Parkinson’s Disease. “It’s amazing that Arthur has invaded my body to the point that I have [seemed] to become him,” the actor would explain in a 1999 interview. “That’s the way people looked at me. But I want people to know I am not intoxicated and… that I am going through this disease as well as I can. But I’m trapped in this body and there’s nothing I can do about it.”

Arthur 2: On the Rocks was dedicated to the memory of the original film’s director Steve Gordon, who died from a heart attack shortly after the release of Arthur. A nice touch, but a film that was hardly worthy of his legacy.

July 13

“Dirty” Harry Callahan would return to theatres on July 13 in The Dead Pool, many critics citing the fourth and last sequel to the hit Dirty Harry series as the best entry since the original back in 1971. That’s almost two decades of precinct rebellion from the dirtiest cop in the business. Quite the survivor! The late Pulitzer Prize winning critic Roger Ebert would even go as far as to call The Dead Pool, “As good as the original. Smart, quick and made with real wit.”

For those who are familiar with The Dead Pool, the movie’s stand-out scene comes in the form of a novel car chase reminiscent of the Steve McQueen classic Bullitt that sees our gruff, no-nonsense protagonist pursued by a suped-up RC10 electric race buggy modified to explode when triggered, a scene elevated by the musical contributions of iconic composer Lalo Schifrin. Director Buddy Van Horn would hire 1985 off-road world champion R/C driver Jay Halsey to execute the scene, the results of which proving an absolute treat that was more in line with the gimmick-hungry 80s than the sobering, urban vigilante leanings of the original movie.

The Dead Pool is also notable for an early Jim Carrey cameo, a future comedy headliner who makes the most of his brief screen time doing his best Steven Tyler impression as a rock star filming an Exorcist parody pop video. I’m sure this scene wasn’t intended to be as funny as it is in hindsight, but Carrey’s rubber-faced potential is there for all to see.

He certainly made an impression on veteran actor Eastwood. Instead of auditioning his scene, Carrey would instead perform his Vegas Elvis Presley act, a comedic splurge that left Clint and his colleagues in hysterics, resulting in the young rookie’s immediate hiring. It was a sign of things to come for an actor who dominated mainstream comedy during the early 90s with headline turns in Ace Ventura: Pet Detective, Mask and Dumb and Dumber.

Though derided by many as the worst in the series, The Dead Pool, a crowd-pleasing adventure stripped of the gritty sociopolitical aspects of previous instalments and the kind of movie Eastwood swore he would never subject Harry to, became the sixth highest grossing movie released in July with a total US box office gross of $37,903,295. Eastwood still retained a fondness for the film, later explaining, “It’s fun, once in a while, to have a character you can go back to. It’s like revisiting an old friend you haven’t seen for a long time. You figure ‘I’ll go back and see how he feels about things now’.”

July 15

July 15 marked the release of two of the decade’s finest movies, though each would receive limited theatrical releases initially, which explains their paltry opening weekends.

The first of those movies was John McTiernan’s innovative action spectacular Die Hard. The story of a New York cop trapped in a corporate skyscraper with a gang of international terrorists, the film was originally set to star Arnold Schwarzenegger until Moonlighting star Bruce Willis turned a corner with his performance as John McClane, defying the typical late-80s, muscles-to-burn template with his proletarian wit and everyman persona. As much as I love Arnie, imagine him in Willis’ place! I’m sure we wouldn’t be talking about the movie in such seminal terms.

Die Hard was high-tech action at its absolute finest, putting much of the bloated genre to shame, McTiernan directing affairs as if wielding a camera-shaped rocket launcher. More than three decades later, it’s still one of the genre’s high points, with believable action and heart by the burning elevator load.

Part of Die Hard‘s success was down to its impeccable casting, characters such as Bonny Bedelia’s steely matriarch Holly McClane and conflicted cop-turned-desk jockey Sgt. Al Powell connecting on a human level that was alien to other action vehicles of the era. Even lesser characters such as cocaine-snorting ‘white knight’ Harry Ellis and happy-go-lucky limo driver Argyle were unusually engaging, providing just the right amount of comic relief while never descending into the realms of pure stereotype. It was because of Willis’ fatigue from such a heavy schedule that screenwriter Steven E. de Souza was forced to flesh out the film’s more peripheral characters, a development that was worth its weight in gold.

Perhaps even more important are the movie’s bad guys. Granite henchman Carl is as memorable as most central antagonists, his side issue with McClane over the death of his brother adding an extra level of tension to an already claustrophobic screenplay. We’re also treated to arguably the finest villain in action movie history in the late Alan Rickman’s Hans Gruber, a smug sophisticate with the slick roguery of a wiry Disney swindler.

Rickman would experience a degree of misfortune while filming what was then the 41-year-old theatre veteran’s first ever Hollywood role. During his first day of shooting, the actor jumped off a three-foot ledge during the iconic Bill Clay scene, damaging some cartilage in his knee. Told not to put any weight on the injured limb by a doctor, he was forced to use crutches for a week, eventually completing the scene by standing on one leg with a brace under his pants. The term ‘break a leg’ has perhaps never been more appropriate.

Die Hard was the most successful movie released in July with a US gross of $83,008,852 and a worldwide gross of $141,278,197 — incredible numbers when you consider that Willis was a relative unknown in Hollywood. One thing you can be sure of: nobody left theatres feeling short-changed.

The second of those movies featured a much more recognisable cast, though it was the film’s least-known comic performer who stole the show. Directed by veteran British filmmaker Charles Crichton, lured out of retirement by the movie’s writer, John Cleese, A Fish Called Wanda is a madcap crime caper that pits American ostentation against British pomposity and absolutely revels in both. Fellow former Python Michael Palin also treats us to a Python-esque series of sketches involving the accidental assassination of three unfortunate Yorkshire terriers in one of the film’s most memorable and disturbing developments.

On the American side of things, Jamie Lee Curtis puts in an incredibly assured comedy shift as a money-crazed harlot who pulls every trick in the book to escape with the swag following a seemingly botched robbery, even going as far as to charm buttoned-down barrister Archie Leach (Cleese) into a long-overdue divorce, a move that results in one of the most unlikely and rewarding romantic pairings of the era.

Despite the endearing chemistry of the movie’s fated romantics, very few will argue that Kevin Kline’s lunkheaded assassin, Otto, a quasi-intellectual who believes the London Underground is a terrorist movement, steals the show. It’s not every day that a typically dramatic performer receives a Best Supporting Actor Oscar for such a ludicrous role, besting the likes of Alec Guinness, Martin Landau, River Phoenix and Dead Stockwell. Quite the achievement.

In Otto, Kline gives us a true comedy icon, a heartless assassin with a penchant for emotional torture who’s as vacuous as he is pretentious. A scene in which he eats stuttering animal lover Ken’s fish as a form of torture is comedy gold, as is his habit of getting high on the smell of his own armpits and bursting into sex-driven bouts of faux-Italian. The fact that a hired killer believes that the central message of Buddhism is ‘every man for himself’ is the ultimate irony.

The movie’s unsung hero came in the form of director Crichton, a veteran filmmaker put out to pasture by an evolving industry that saw no place for his antiquated methods. Crichton’s previous movie, British crime drama He Who Rides the Tiger, had been made all the the way back in 1965, and at 78 the notoriously ruthless film business was hardly likely to give him a sentimental swansong based on past achievements. Cleese, who was a big admirer, felt differently, even crediting himself as co-director in a move that allowed Crichton to produce arguably his greatest work.

A Fish Called Wanda was the third most popular movie released in cinemas in July with a US gross of $62,493,712.

July 20

After a decade of mostly serious roles, Robert De Niro would try his hand at comedy during the late 80s and early 90s with typical aplomb, starring in such classics as Martin Scorsese’s deliciously dark The King of Comedy and John McNaughton’s overlooked crime caper Mad Dog and Glory, a movie produced by Scorsese as a way to bring back the long-ostracised filmmaker (McNaughton would struggle to find work on American shores thanks to debut picture Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, a grubby character study that wowed critics but failed to break through certain commercial barriers).

Of all those comedies, 1988’s hugely endearing buddy movie Midnight Run is arguably the most enjoyable, thanks in large part to the immediate onscreen chemistry of De Niro and comedy actor Charles Grodin. The tale of a former cop-turned-bounty hunter tasked with bringing a thief to justice, only to be faced with an increasingly tough-to-swallow moral dilemma (Grodin’s Jonathan ‘Duke’ Mardukas actually turns out to be something of a philanthropist), the film also benefits from memorable secondary turns from Dennis Farina, Yaphett Koto, a young Joe Pantoliano, and Beverly Hills Cop‘s John Ashton as a bumbling bounty hunter looking to cash-in on rival De Niro’s latest target. Ashton was purportedly astonished by how seriously De Niro approached the role, particularly when his co-star became so involved with a scene that he actually punched Ashton for real.

De Niro may never have starred in Midnight Run if he’d had his way. Having just completed work on Brian De Palma’s prohibition crime drama The Untouchables, the actor would approach director Penny Marshall about starring in Big (imagine that!), and though she was interested in working with arguably the greatest actor of his generation, producers decided on Tom Hanks, and the rest, as they say, is history.

Producers were also keen on the much more high-profile Robin Williams for the role of Mardukas, director Martin Brest ultimately insisting on Grodin based on his chemistry with De Niro (it’s hard to believe that the frenetic Williams could have pulled off the subtle, likeable irritation that Grodin manages to conjure, which is key to the movie’s magic). Due to his often manic attention to detail, De Niro convinced Grodin to wear real handcuffs as opposed to the usual plastic props during certain scenes. To this day, the actor still has the scars to show for it.

Interestingly, Grodin’s character almost became a female. Still craving a more universally recognised actor, Paramount Pictures pitched the hugely popular Cher as the film’s slippery fugitive, also feeling that a female foil would open the film up to “sexual overtones”. Though the screenplay is somewhat bloated, the film boasting an unusually long running time of 126 minutes, Midnight Run would become the fifth highest grossing movie released in July, with a healthy domestic return of $38,413,606.

July 22

July’s third and final sequel is regarded by many as being one of the worst committed to celluloid, a feeling no doubt exacerbated by the fact that it’s antecedent is one of the best-loved cult comedies of the decade.

Caddyshack II was panned by audiences and critics alike for its uninspired screenplay and mundane direction, though the fact that the follow-up to such a bawdy classic was shackled with a PG rating certainly didn’t help. Not even an all-star cast that included such comic royalty as Randy Quaid, Dan Aykroyd and a returning Chevy Chase could save this one from the bunkers of mediocrity. No wonder Bill Murray is notable by his absence.

This time around, the daughter of a self-made millionaire hooks up with a silver spoon WASP, who convinces her and her crude father (Jackie Mason) to join their country club. Needless to say, the other members are unimpressed by his straight-shooting attitude and intrusive sense of good cheer. I’ve leave the rest up to your imagination; you won’t need very much of it. As you can probably guess, Dan Aykroyd is given gopher disposal duty in the absence of fellow Saturday Night Live alumni Murray, but not even the driving force behind Ghostbusters can save this one from Mulligan territory.

The late Harold Ramis, director and co-writer of the original Caddyshack, would begin writing the sequel before ultimately dropping out. As he would explain in an interview with AV Club, “…with Caddyshack II, the studio begged me. They said, ‘Hey, we’ve got a great idea: ‘The Shack is Back!” And I said ‘No, I don’t think so.’ But they said that Rodney [Dangerfield] really wanted to do it, and we could build it around Rodney. Rodney said, ‘Come on, do it.’ Then the classic argument came up which says that if you don’t do it, someone will, and it will be really bad. So I worked on a script with my partner Peter Torokvei, consulting with Rodney all the time. Then Rodney got into a fight with the studio and backed out. We had some success with Back to School, which I produced and wrote, and we were working with the same director, Alan Metter. When Rodney pulled out, I pulled out, and then they fired Alan and got someone else [Allan Arkush]. I got a call from [co-producer] Jon Peters saying, ‘Come with us to New York; we’re going to see Jackie Mason!’ I said, ‘Ooh, don’t do this. Why don’t we let it die?’ And he said, ‘No, it’ll be great.’ But I didn’t go, and they got other writers to finish it. I tried to take my name off that one, but they said if I took my name off, it would come out in the trades and I would hurt the film.”

We still love you Harold.

July 29

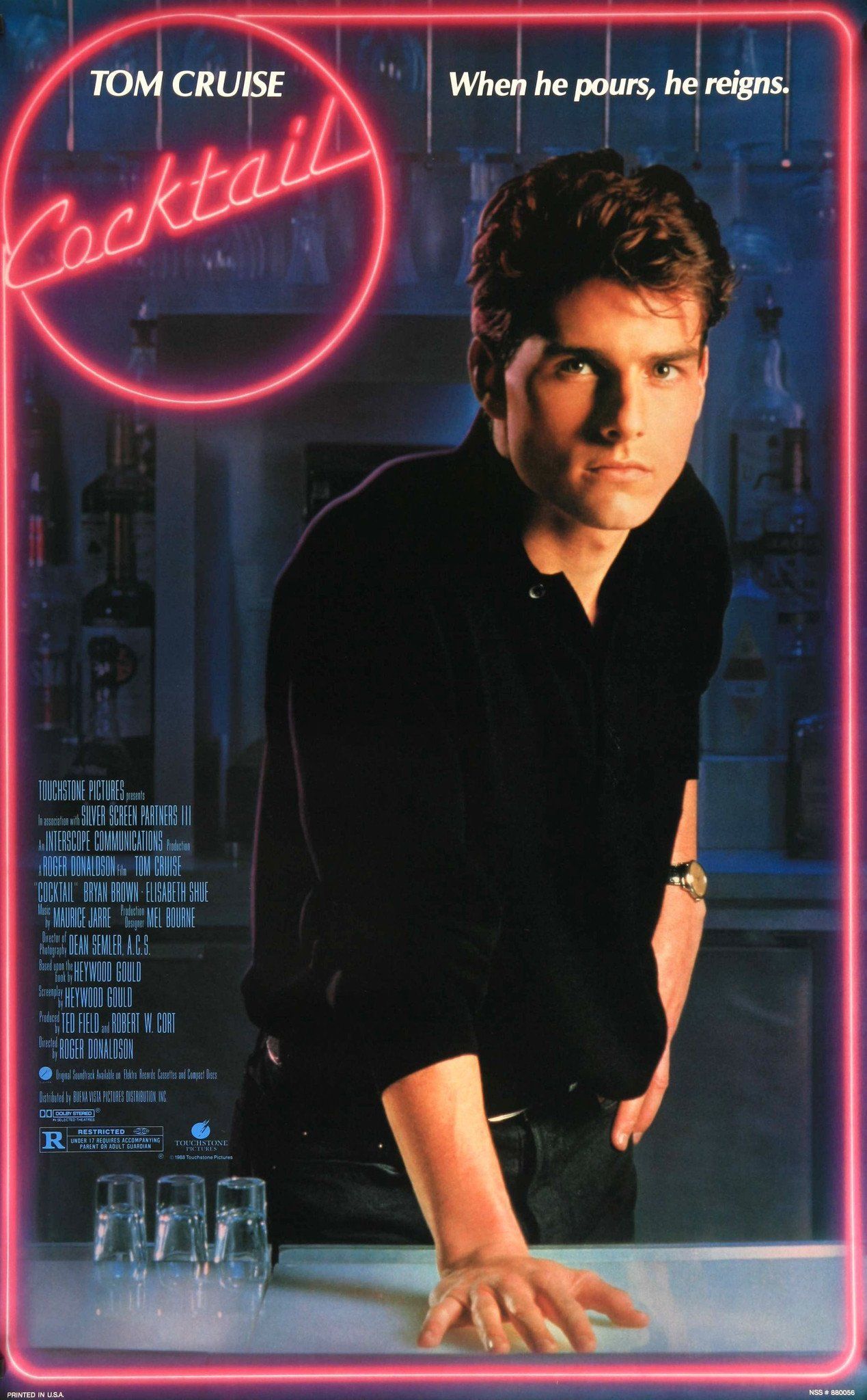

Things would get marginally better on July 29th with Tom Cruise vehicle Cocktail. Co-starring Aussie import Bryan Brown as a ruthless shyster and dubious mentor to Cruise’s wet-behind-the-ears business student looking to make a million, Cocktail is the rather curious tale of two ‘flair bartenders’ who use their skills to pick up loose women, eventually moving to Jamaica, where wealthy spinsters mean big bucks. That’s until love interest Jordan Mooney (Elisabeth Shue) drifts into protagonist Brian Flanagan’s life to spoil the party.

Though the movie turns out to be surprisingly dark, it was criticised for its shallow screenplay and inability to tap into Cruise’s mainstream charms. It’s hard to disagree. Only in the 80s could such a shallow concept be given the blockbuster treatment and exceed all commercial expectation. In fact, the movie was only financed after Cruise showed an interest.

As emotionally stilted as Cocktail is, there’s no doubting its credentials as a kitsch time capsule for 80s excess, an era when bigger was better and personal glory was the name of the game, but you may need rose-tinted wayfarers and a hollowed-out pineapple libation to get through this one. It’s lacking that certain spark synonymous with Cruise for the most part.

Ironically, the late Robin Williams, a known manic-depressive who would take his own life on August 11, 2014, was once again considered for a prominent 80s role that ultimately went elsewhere, this time Brown’s Doug Coughlin, a character who also chooses suicide after years of conman philandering and booze-soaked decadence inevitably catch up with him. It’s fairly powerful stuff, though somewhat out of place for a movie that’s headlined by a young heartthrob like Cruise.

Surprisingly, a film that was based on screenwriter Heywood Gould’s semi-autobiographical novel of the same name was originally set to be much darker until distributor Disney got involved and pushed for Cocktail to be more cinematic, something Gould was resistant to but ultimately agreed was the correct decision. “They wanted movie characters. Characters who were upbeat and who were going to have a happy ending and a possible future in their lives,” Gould would explain in an interview with the Chicago Tribune. “That’s what you want for a big commercial Hollywood movie. So I tried to walk that thin line between giving them what they wanted and not completely betraying the whole arena of saloons in general.

Cruise was one of the hottest young stars in Hollywood in July ’88 following a spate of blockbuster hits that included cult teen sex comedy Risky Business, MTV-styled power surge Top Gun and Martin Scorsese’s uniquely conventional pool hall drama sequel The Color of Money. It should come as no surprise that Cocktail was second only to Die Hard in the Box Office charts for July, bringing in a cool $78,222,753, with a rather impressive opening weekend of $11,789,466 — the best by some margin. Never underestimate the pull of star power.