Director: Sandor Stern

18 | 1hr 43min | Horror, Thriller

Let me put it out there right off the bat: Pin is one hell of a messed-up movie. This may be old news to long-time fans of Sandor Stern’s delightfully twisted Canadian horror, which, having struggled to find an audience, has become something of a cult favourite in the darker, more obscure corners of horrordom, a place where it resides, much like the film’s impenetrable antagonist, with a disquieting patience that will not be denied. But despite my peewee horror obsession peaking that very same year, I didn’t stumble upon Pin‘s toe-curling charms until this past week, my only regret being that I failed to discover it sooner.

Pin‘s relative obscurity was due to unfortunate timing. New World Pictures were in the process of dissolving its film division as production wrapped, and though Pin was intended as their final theatrical release, executives decided against it following a negative test screening that saw them pull their resources at the last minute. The movie was instead released direct-to-video on May 28, 1989. Interestingly, it was already considered an underrated and overlooked film in 1991 after successful screenings in Manhattan and San Francisco. Watching it, you definately get that impression.

Glibly chosen as yet another late-night YouTube freebie to fall asleep to, I wasn’t expecting much from Pin, which made it all the more impactful. Sometimes you find a silly gem that keeps you up a little late, that you resume the following evening out of morbid curiosity, but mostly it is lights out during the first act of movies that are so strewn with pace and coherency issues that you quicky fall prey to the inevitable slumber (there’s typically a reason why these movies are free and remain that way unchallenged). Contrarily, Pin defied all lazily acquired expectations with its distinct lack of silliness, in spite of a concept that, handled even remotely poorly, could have gone that way rather quickly. Despite its obvious lack of budget and in some ways because of it, Pin is a very well executed movie that rarely takes you out of the moment.

This wasn’t the first time I’d heard of Pin. I was quietly aware of the movie, had been from a very early age, but the details were sketchy, and the film’s innocuous title, a rarity that no doubt contributed to its relative anonymity, did little to encourage. I’d stared at Pin’s equally disquieting promotional poster in the cobwebbed crannies of my old VHS rental haunt, but in an era of bloated slasher killers, waning horror franchises and practical effects burnout (the A Nightmare on Elm Street series, I’m looking at you), it never qualified as a reasonable pocket money investment. It just rested there, quietly collecting dust with a queer, if somewhat formidable ambivalence, the kind that permeates Pin‘s every sordid whim.

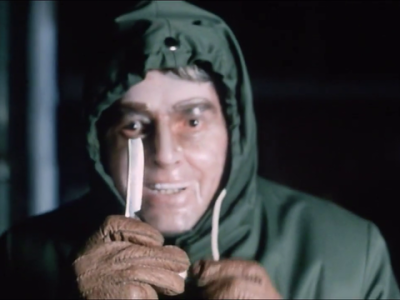

Made in the uneasy, psychological traditions of Ealing Studios Dead of Night favourite The Ventriloquist’s Dummy and William Goldman’s deftly orchestrated chiller Magic, Pin, adapted from Andrew Neiderman’s 1981 psychosexual novel of the same name, revolves around a seemingly inanimate, anatomically correct medical dummy that is initially brought to life by the flawless ventriloquist skills of a doctor and father, a mild authoritarian who uses Pin as a conduit for life lessons, forging an imaginary friend for his besotted outcast of a son and unaturally curious daughter. Thanks in large part to the effortlessly sinister aura of The Stepfather‘s Terry O’Quinn, making the most of a cameo as the dad in question, the movie plays with expectation by setting him up as the film’s deranged villain in the Antony Hopkins mode, a character with a loosening grasp on reality who will succumb to the growing powers of his own delusions, but Pin quickly distances itself from such derivative aspirations, and to its credit.

Some of those earlier moments, sexualising kids who are yet to reach double figures, are truly disconcerting. They certainly wouldn’t exist in today’s hyper-informed climate, riding a tenuous wave that poses deeply uncomfortable questions. Had we not segued early on, leaping forward to the kids’ teenage years, it may have proven a problem, but when a 15-year-old girl, pregnant and lambasted for whoring herself out to the high school football team, is the cooler side of the pillow, you know you’re in for a rough ride morally. By that time Leon (David Hewlett), played with an introverted madness that Psycho‘s Anthony Perkins would have been proud of, has convinced himself that Pin is real, taking sister Ursula (Cynthia Preston) to see the apparently lifeless model for some parental advice.

This is the first of several creepy scenes involving Leon, Ursula and an increasingly obtrusive Pin, who soon inhabits a prominent place at the bequeathed family mansion, becoming a ruthless confidant for our ferociously controlling patriarch, particularly when a well-meaning aunt shows up in a misguided attempt to establish some stability. Ursula is understandably convinced that Leon, a loner who forms a formidable bond with Pin, has taken over ventriloquist duties, but thanks to the film’s understated craftsmanship, it is somehow never clear, even when O’Quinn’s doctor discovers his son’s psychotic tendencies and attempts to remove Pin from his life, only for he and his wife to suffer the fatal consequences. At the hands of the dormant Pin? Surely not. Though there’s an utterly convincing case for definitely maybe.

More conflict rears its ugliness when a mild-mannered high school jock takes a liking to Ursula, now working part-time at the town library to escape her brother’s increasingly erratic behaviour. This often extends to manic bouts of domestic violence stemming from Ursula’s rejection of Pin, bibbed and dressed to look more human at the head of the dining room table, as a sentient member of the Linden homestead, or ‘brother’, as Leon suggests following one of several searing smacks across the face. Though their well-meaning yet cold and creepy father certainly played a part in Leon’s worsening condition, especially when demanding that he reveal Pin’s genitalia to his younger sister (using Pin’s voice no less), research has led Ursula to believe that her brother is in fact a paranoid schizophrenic. Supernatural forces or no supernatural forces, I could have told her that for free.

Thanks to a few formative moments that I will expand upon, both offspring are messed-up mentally, operating at opposite ends of the psychosexual spectrum, be that Ursula’s wanton promiscuousness or Leon’s slasher-like aversion to anything even remotely carnal. Naturally, the latter of whom, while refusing to partake in physical contact with the opposite sex, opting to terrify a local teen who he initially invites over for intercourse, is far more destructive, the threat of violence and torment festering in an obsessive manner reminiscent of Peeping Tom‘s unquenchable voyeur Mark Lewis. Leon even decides to share some of his precious poetry with Ursula’s beau Stan, the theme of which, mercifully eluding an increasingly worried and protective Ursula, coming a little too close for comfort. Taken literally, it appears that Leon has a burning and barely repressed desire… to rape his own sister.

While Pin is nothing short of brazen in its relationship with the uneasy, tackling perverse themes head-on, its calculated, stripped-back presentation, a throwback to the suggestive horror of yesteryear, is an absolute pleasure, the complete antithesis of late-80s excess. It’s all so skilfully delivered too, featuring comparatively formidable performances from young actors who would have been reduced to undeveloped fodder in the latest Friday the 13th instalment. Despite its financial limitations, there is little room for laughable melodrama here. Fine performances aside, the themes, tone and deliberate, convention-dodging nature of the screenplay don’t allow for it. Pin is the very definition of an underappreciated gem that has to go down as one of the best underseen horror movies of the decade.

Though not dependent on it, much of Pin‘s power lies in its ability to convincingly blur the margins, to maintain doubts about our eponymous villain’s possible sentience and the complexities of its relationship with an increasingly worrisome Leon. A lesser movie, particularly in a CGI-heavy climate, would likely have rushed to such a reveal, descending into a popcorn frenzy of wild slashings that would have quickly unravelled the patient foreplay of a much more interesting and tricky approach, but Pin embraces the concept to the bitter end. On the surface, it is far better suited to the literary format, suggestion and imagination the key ingredients, but Stern, who also handled the screenplay, does a wonderfully convincing job of recreating it for the screen. It’s really quite the achievement.

If all of that wasn’t enough, Pin ends with a superlative bang that, despite Stern’s convention-swerving efforts to lead us along a familiar path that simply doesn’t exist, I just didn’t see coming. That movie’s final image is the perfect swansong for a surprisingly competent low-key treat, a microcosm of Pin‘s ability to disturb, unnerve and keep its audience deliriously in the dark. Sometimes you discover a film, quite by chance, that delights in its ability to curb the lazy preconceptions ground into us by countless low-budget duds with derivative aspirations that border on the derisive. I just didn’t expect Pin to be one of them.

Growing Pains

As previously stated, Pin treads seriously touchy ground during those earlier scenes, the most notable of which occurring in the soon-to-be-late Mr Linden’s doctors office.

After a preteen Ursula is caught with pornographic material, her father takes she and her brother to see Pin, using his ventriloquist act to relay to them the facts of life and the inevitability of human reproductive urges.

While knowledgeable and informative, the Pin/father axis is also gobsmackingly inappropriate when discussing ‘the urge’ and ‘the need’, demanding that Leon remove a towel concealing Pin’s reproductive organs. Queerly enthusiastic, Ursula announces that she can’t wait to be old enough to get ‘the need’.

“I think I’m REALLY gonna like it,” she concludes.

This after a not-so-humorous suggestion that her mother “washes father’s penis with Spick ‘N’ Span” before intercourse.

Formative Years

Pin’s power to infatuate is not confined to the naïve and mentally ill, though given our next character’s actions, a padded cell might not be too far out of reach.

Early in the movie, while a pewee Leon secretly confers with Pin, he suddenly finds himself hiding in his father’s office when a middle-aged nurse lets herself in after hours, gazing amorously at the viscera-veneered dummy with the vaguely human eyes staring back at her.

Confident she is alone, the woman then simulates sex with Pin on the doctor’s table, orgasming to a powerful climax as Pin thrusts lifelessly on top of her. But who is in control here?

Fine Margins

Dealing with a seemingly inanimate evil in films can be tricky (just ask the creative teams behind some of those ludicrous Amityville sequels), but Stern has no such troubles, presenting events with a deftness that keeps us guessing to the very end, despite overwhelming evidence of Leon’s mental instability.

While totally improbable, Pin’s possible sentience continues to claw away at your suspension of disbelief, be that through creepy dialogue, potential acts of murder or unfettered sexual exploits.

I certainly wouldn’t want it anywhere near my house.

Interesting Titbit

The horrendously creepy Pin was voiced by 80s mainstay Johnathon Banks (Beverly Hills Cop), who many of you may know as Mike Ehrmantraut from TV hits Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul.

Choice Dialogue

Though Pin is littered with several instances of mind-blowingly creepy dialogue, I thought it appropriate to concentrate on an excerpt from the seriously batshit Leon’s book of prose:

Leon: [to Ursula and boyfriend Stan] “In these lines, [the character] is contemplating rape for the first time. ‘The closer she came to him, moving, it seemed in silent motion. His heart beats steadily within the caverns of his bosom, driving hot blood, thick, down into the depths of his loins. He lunged from the deepest, darkest passions in us all. She turned without sound. And faced him. He stopped abruptly. It was as if a knife had performed an instant castration. He was looking into the eyes of his sister.'”

Talk about choosing your moments!

A seriously twisted psychosexual thriller that shows admirable constraint where is counts,

Edison Smithis a superbly made, surprisingly convincing gem that punches well above its potential, putting many of its conceptual peers to shame. Do proceed with caution, however. It’s what Pin would have wanted.