Exploring America’s relationship with narcotics through the lens of Frank Henenlotter’s exploitation classic

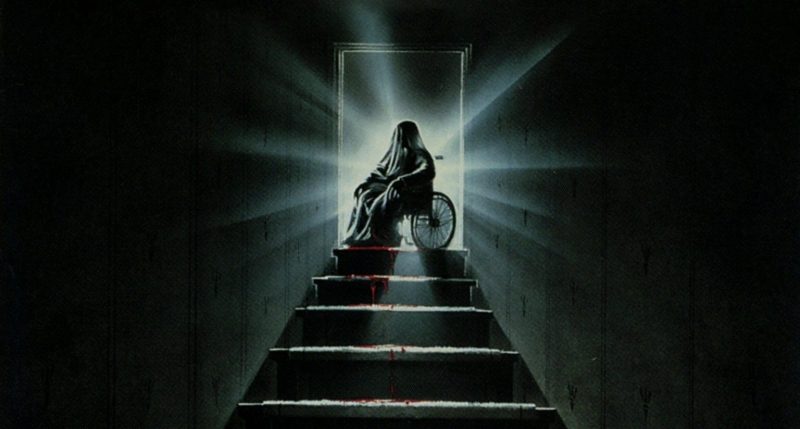

Sometimes a movie comes along that really takes you by surprise. Brain Damage is much more than trashy B-movie horror. It has all the ingredients, but behind the bad taste presentation there’s a film with a social conscience — a dreamy, often brutal commentary on the pitfalls of drug addiction which far exceeds its budget, displaying visual ingenuity one can’t help but admire. It also features one of the most endearingly devilish antagonists of the 1980s, a bona fide smart ass who rivals peak Fred Krueger with his inimitable brand of ironic sadism. The fact that parasitic brain slug, Aylmer, failed to inspire his own franchise is one of exploitation cinema’s biggest tragedies.

This is even more surprising since Brain Damage is the brainchild of exploitation legend Frank Henenlotter, a delightfully twisted filmmaker who possesses more depth and social awareness than cult movies such as Frankenhooker and Basket Case may at first suggest. Like Brain Damage, those movies are fuelled by seemingly fantastical concepts. Basket Case tells the story of conjoined twins separated at birth, one a geeky introvert with a grudge to bear, the other a murderous, basket-bound blob with a taste for women’s panties. Frankenhooker is even more out-there, the tale of a suburban sweetheart, killed in a lawnmower accident, who’s brought back to life by her genius boyfriend as a veritable Frankenstein’s Monster, one forged from the limbs of dead hookers blown-up having consumed a sinister new drug named ‘super crack’. Hardly the grounds for conventional social commentary.

All three movies take place in New York’s sleazy underbelly, represented with such grimy authenticity that it gives Henenlotter an edge otherwise lacking in not only mainstream cinema’s depiction of inner city squalor, but most exploitation fare ― think Scorsese’s stylish, anthropological Taxi Driver stripped to the budgetary bones. Due to his production limitations and eye for the city’s seedy cracks, his films possess the raw realism of crudely captured footage, the kind you might find stored for preservation in the basement of a big city art gallery. For ‘dirty, golden age New York enthusiasts they’re a real time capsule.

Henenlotter typically deals with skid row denizens who inhabit dark corners, but they’re not written off as inhuman crooks, shady nogoodniks or drug-addled wasters. Even those that carry such a stigma are colourful enough to be endearing or human enough to come across as sympathetic. “I always felt that I made exploitation films”, Henenlotter would say. “Exploitation films have an attitude more than anything – an attitude that you don’t find with mainstream Hollywood productions. They’re a little ruder, a little raunchier, they deal with material people don’t usually touch on, whether it’s sex or drugs or rock and roll.”

The beleaguered protagonist of Brain Damage, Brian — a name which, surely intentionally, is an anagram of brain — is certainly worthy of our sympathy. He’s not as colourful as some of the hookers or pimps who can be found in Henenlotter’s other movies, or as deranged or idiosyncratic as some of his other protagonists, but he’s destined for the same environment, his life in a shitty rented apartment giving way to the non-discriminatory perils of addiction. Brian’s habit begins as a form of escapism, a colourful, mind-altering retreat from the harsh realities of inner city life, but like all addicts it quickly goes south, the all-consuming abstractions giving way to a physical and emotional nightmare of inescapable slavery. The fact that Brian’s particular poison assumes the form of a living, breathing entity who revels in his ability to control and dominate is what makes us sympathise with him so strongly.

This is the start of your new life Brian, a life full of colours, music, light and euphoria. A life without pain, or hurt or suffering.

Aylmer

Those early scenes from Brian’s drug-induced perspective, though bargain-basement primitive, are very much representative of a real pshycadelic experience: the shifting brightness, those liquid sensations, the propensity to focus on a particular image and become lost in unimaginable, barely graspable details that continue to evolve, the ostensible dissolution of time and place, all of it cradled in a lullaby of audio experimentation. Everything is an unbelievable adventure just waiting to be explored. You can tell that Henenlotter and his team were no strangers to mind-altering substances. Though Brian’s trips become much darker as his addiction worsens, those earlier scenes hint at the serene, liberating effects of certain stimulants, the kind that grow naturally and have been proven to have positive benefits. Look a little closer and Brain Damage isn’t the anti-drug polemic many had it pegged for.

Not all drugs are bad, some are great, and I write that without a hint of humour. Drugs, particularly the psychoactive variety, can be absolutely liberating in terms of creativity and extremely valuable medically, despite what systems of power and pharmaceutical companies continue to suggest. Marijuana is becoming legal in more and more states and psilocybin, the naturally occurring psychedelic compound found in certain species of fungi, known to inspire emotional clarity and truth-inducing qualities, is being treated to cure depression. So indebted to marijuana was the jazz community during the early-mid 20th century that weed proponent Louis Armstrong wrote a letter to president Dwight D. Eisenhower pleading that he make the drug legal after discovering that Bing Crosby had somehow attained a waiver to cultivate it, citing the drug as his main creative inspiration. ‘Satchmo’ would have his request denied, the drug becoming a convenient form of probable cause amid Civil Rights tensions, but he would have the last laugh, later tricking staunch anti-drugs president Richard Nixon into smuggling three pounds of marijuana through customs. The State Department had made Armstrong a Goodwill Ambassador for the US, and a clueless Nixon, who wasn’t subjected to searches, was only too happy to carry his bags for him.

Of course, the State Department, and the propaganda outlets that spin their narratives, have historically presented drugs in a very different light. I’m not advocating drugs as a whole, many of them have little-to-no spiritual value and/or promote addiction, ruin families and destroy whole communities, but harmless drugs such as marijuana were tarred with the very same brush, most famously in Louis J. Gasnier’s 1936 propaganda film Reefer Madness. A ludicrously melodramatic deterrent for America’s youth that begins with a marijuana-motivated hit-and-run accident, jumping to manslaughter, suicide, conspiracy to murder, attempted rape and all-out madness which propagated the dangerously addictive qualities of a non-addictive substance, Gasnier’s wildly overblown 60-minute onslaught has since become a cult favourite among stoners for its unintentional satirical qualities. If you haven’t seen it, I suggest you do so. It’s an exquisite microcosm of America’s groundless and reactionary multibillion-dollar smear campaign against a substance that is set to become the new darling of commercial capitalism.

Aylmer’s alien super-drug or ‘juice’, a blue liquid excreted through a tiny needle directly into the brain, possesses all the spiritual benefits of non-addictive psychoactive drugs, but all the pitfalls of addiction. Due to the drug’s otherworldly powers, Brian’s appetite turns insatiable very quickly, reducing him to the kind of rube that Aylmer requires in order to feed his own insatiable habit: fresh, preferably live, human brains. Aylmer’s previous owners, an elderly couple deep in the throes of addiction, have managed to domesticate Aylmer, feeding him animal brains with a sprig of garnish like a common house cat. This keeps the creature weak, and you don’t want Aylmer growing strong, something Brian, and we the audience, quickly come to realise. One morning Brian wakes up feeling a little worse for wear, fearing he’s caught a virus. In reality, Aylmer, injecting him in his sleep, has already set him on the path to physical and emotional slavery. They say addiction creeps up on people. Never has that expression been so deliciously literal.

Brilliantly voiced by the late television horror host John Zacherle, Aylmer is the real star of Brain Damage, sadistically starving his victims to the point of insanity and consistently upping the ante, demanding more brains for less juice with a gleeful relish-come-gameshow host congeniality that will leave you scoffing at the impudence. It’s no surprise that Aylmer’s lineage goes back centuries. His juice is responsible for some of history’s most astonishing creative achievements, as well as some of its bloodiest atrocities, an indicator of drugs as a double-edged sword. He’s absolutely vicious too, leaping headlong into unabashed savagery at the merest whiff of brains and ravenously tunnelling for the sentient treats within. The notion of Alymer masterminding the fall of empires in order to feed his cerebral gluttony, leaping from brain to brain on the blood-strewn battlefields, never fails to leave me chuckling. He’s proud of his achievements, too, extolling the virtues of his dominance with a supercilious glee. His eyebrows wiggle suggestively at the very hint of human misfortune, his dry, malevolent wit delivered with a gentle irony that chimes like an insidious lullaby in the subconscious.

Like addiction, Brain Damage isn’t all fun and games, thanks in no small part to special effects artists Gabriel Bartalos and Al Magliochetti, who pile on the gore and squeamish body horror, bringing Aylmer and his psychoactive assaults indelibly to life through a winning combination of puppetry, stop-motion animation, practical effects, and rotoscoping, all of it laced with Henenlotter’s particular brand of gallows humour. One particular scene, darkly humorous thanks to Aylmer’s sinister taunting and quietly insightful dialogue, is still absolutely excruciating to behold, Brian succumbing to his tormentor’s powers of persuasion after attempting to go cold turkey. It’s all so bleak and dingy, descending into the drudgery of withdrawal with a hopelessness that temporarily wipes the smile clean off your face. At one point, deep in the proverbial bowels of sickness, an hallucination sees Brian rip a forty-foot rope of human tissue from his ear canal before vomiting his body’s weight in blood. It’s an absolutely gut-wrenching experience, both emotionally and physically.

Hey, it feels like you’ve got a real monster in there!

Girl from Nightclub

In terms of body horror, there’s certainly a hint of Cronenberg at play. Brian, retreating from the world like most junkies consumed by addiction, experiences initial pangs of sickness as the juice begins to take its toll, his hallucinations, taking on a darker persuasion, bleeding into reality like a burst blood clot (some of those pulsating, rotoscoped brain effects are positively icky). Visions of mutated orgies and brain-devouring haunt Brian’s nightmares, but the line between dreams and reality grows ever more tenuous as the high fades under the agitated banality of everyday life, his spaghetti and meatballs, ordered at a restaurant in the throes of psychological withdrawal, transforming into throbbing, breathing brains in a manner reminiscent of Videodrome. Yielding to the drug’s growing omnipotence, Brian is transformed from a semi-conscious, unwilling accomplice into a knowing accessory to murder, and nobody’s safe, not even his needy, harmless and deeply concerned girlfriend, Barbara (Jennifer Lowry), who slips further into obscurity until Aylmer smells fresh meat.

The film’s most controversial scene, though endearing for its sheer audacity, just wouldn’t exist in today’s hyper-sensitive climate. Not that it was much different back in 1988. In fact, the entire crew walked off set, initially refusing to shoot the infamous death-by-fellatio scene for ethical reasons, and it’s still an astonishing watch, a full-force smack in the face on a particularly frosty evening. While out getting his rocks off, Brian, exhibiting some of the worst dance moves this side of the Macarena, is led along the back alley of a night club by a leather-clad harlot looking for some after hours titillation. Reaching into his zipper, she instead finds a phallic-shaped Aylmer, who quickly becomes a substitute for his carriage’s penis, a drugged-to-the-eyeballs Brian simulating a full-on blowjob with the brazenness of a late-80s porno, thrusting the creature in and out of her mouth while lost in a blinding rainbow of euphoria. Seizing his chance for a late-night snack, our strangely endearing parasite finally pulls the poor girl’s brains out through her mouth in what is hands-down the most perverse instance of symbolic ejaculation ever committed to celluloid. It’s a moment you’ll be talking about long after the credits roll, the film’s money shot if you will, so approach with caution.

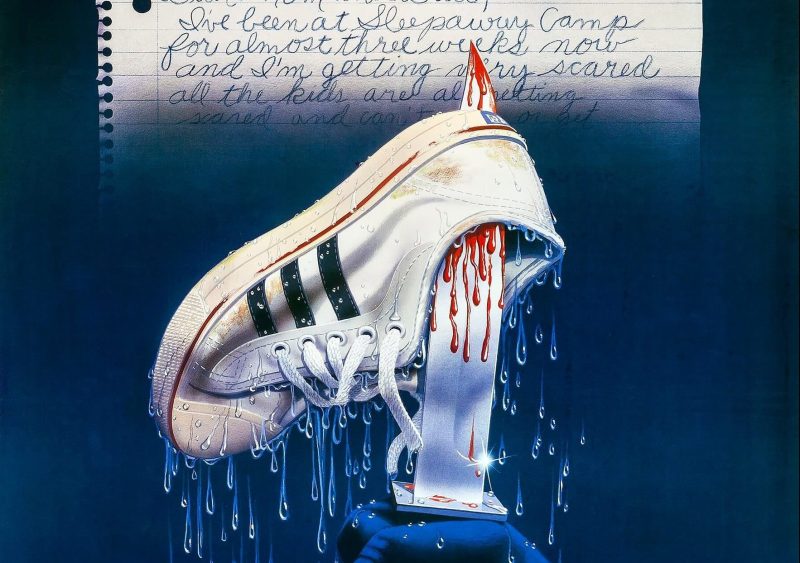

Brain Damage was released at a tenuous time for American society, especially those living on the fringes who were pushed out to sea during Ronald Reagan’s rampant privatisation model. Not only were the inner cities plunged further into poverty ― particularly late-80s New York City, a former quagmire of vice, robbery and murder that was gearing-up for widespread gentrification and corporate power’s commodification of public space ― they were consumed by the nation’s devastating crack epidemic, minority communities destroyed by addiction and gang culture as the prison construction boom sought inmates to fulfil the nation’s industrial advancements.

Rather than understand addiction, victims were demonised, tax dollars that could have been used to fix the situation instead used to enforce harsh penalties on minor drug possession, while laws on the affluent powder cocaine, a favourite of high society, were suspiciously loosened. When Reagan took office in 1980, the total prison population was 329,000. When he left office eight years later, that figure had essentially doubled to 627,000, black and Latino males constituting a worryingly high percentage of those numbers. It should also be noted that the Reagan administration overlooked the importation of cocaine during the Iran-Contra affair, a political scandal that saw senior administration officials secretly facilitate the sale of arms to the Islamic Republic of Iran, the funds of which used to back right-wing rebel group the Contras in Nicaragua. The hypocrisy was nothing short of astonishing.

Well, well… ready to beg for it, Brian? Ready to crawl across the floor and plead for my juice? No? Not yet? Well, give it a few more hours, Brian. Whenever you want the pain to stop, I’ll be here. Whenever you want to stop hurting, you come to me. When the pain gets so great you think you’re turning inside-out, just ask for my juice.

Aylmer

When it comes to addiction, it’s always easier and more convenient to blame the user. Those who fail to understand addiction tend to see it as a simple choice, a weakness that’s somehow beneath them. This was especially true during the 80s, a time when addicts were depicted as a selfish, wasteful scourge with no path to salvation. Salvation is a relevant word in this instance since those who demonised the likes of Brian were typically fundamentalist Christians towing the Republican bandwagon, flying the flag for Ronald and Nancy Reagan’s hypocritical War on Drugs. Anyone around in the late-80s will remember those deeply condescending commercials featuring an all-American Joe, a cracked egg and a sizzling frying pan. “This is your brain, this is your brain on drugs.” That’s as far as the science went.

Throughout history, drugs and drug users, many of them isolated, helpless and bereft of hope, have been targeted for scrutiny, becoming political fodder for governments looking to smear and degrade low-income minorities and cut public funds, to run people out of their homes for the sake of property-developing lobbyists, to fill their prisons and financial quotas. In an era of mindless vilification masquerading as moralistic endeavour, Henenlotter takes a more open-minded approach to the subject matter. In Brian he forges an addict who, despite the abhorrent acts he’s forced to commit, the kind that transcend those petty crimes typically synonymous with addiction, is very much worthy of our sympathy, not least because the morally reprehensible inner voice that pushes and urges and motivates assumes a living, breathing form, an extra-terrestrial scourge who remains largely invisible. It’s nothing short of amazing that such an overtly schlocky, gore-laden exploitation vehicle is capable of such empathy, the kind that would give high society’s naval gazers further ammunition. It’s a delicious irony that only adds to the filmmaker’s caustic clout.

Ultimately, disappointingly, Brain Damage is one of those movies that they just don’t make anymore, the kind conceived during the home video boom that presented directors with an almost lawless canvas, and few took advantage quite like Henenlotter. These were low-cost, low-risk productions that relied almost entirely on out-there charm, and Brain Damage is such a unique and wonderful oddity, a sweet and sour treat that’s almost worryingly satisfying. Henenlotter brings a tremendous sense of authenticity to his movies. They’re exploitative — unrepentantly so — but despite some intensely peculiar scenarios and gobsmacking instances of sleaze, they’re somehow strangely relatable, human in the most inhumane sense.

It’s rare that you find such an openly trashy movie with such a thematically compelling centre, or a character who proves as twisted as they are bewitching. Aylmer is a cruel, unforgiving mistress, one you might enjoy sharing a cigar with next to an open fire (providing you can supply the brains). He’s such an unconscionable heel, cartoon supervillainy trapped in a miniscule, borderline-adorable package. There are even times when you feel like petting the little bastard. Like all successful serial killers, you kind of dig the vaguely human façade.

As Aylmer, arguably Henenlotter’s most unique and endearing creation, a wicked, meanspirited parasite who proves so irresistible so fittingly croons, “Why are the stars always winkin’ and blinkin’ above? What makes a fellow start thinkin’ of fallin’ in love? It’s not the season, the reason is plain as the moon. It’s just Aylmer’s tune!

Director: Frank Henenlotter

Screenplay: Frank Henenlotter

Music: Gus Russo & Clutch Reiser

Cinematography: Bruce Torbet

Editing: Frank Henenlotter & James Y. Kwei

Still haven’t got around to seeing this. I was young in the Reagan-era climate but remember it alongside his alliance with Thatcher. I think I remember more the ‘war on drugs’ via the first George Bush era. I still have my copy of Reefer Madness on DVD which is just hilarious and astonishing to see, and makes a good double-bill movie night with Cheech & Chong: Up in Smoke 🙂

LikeLike

Damn! Reefer Madness and Up in Smoke. Sign me up!

LikeLike