Director: Michele Soavi

18 | 1h 30min | Horror, Slasher

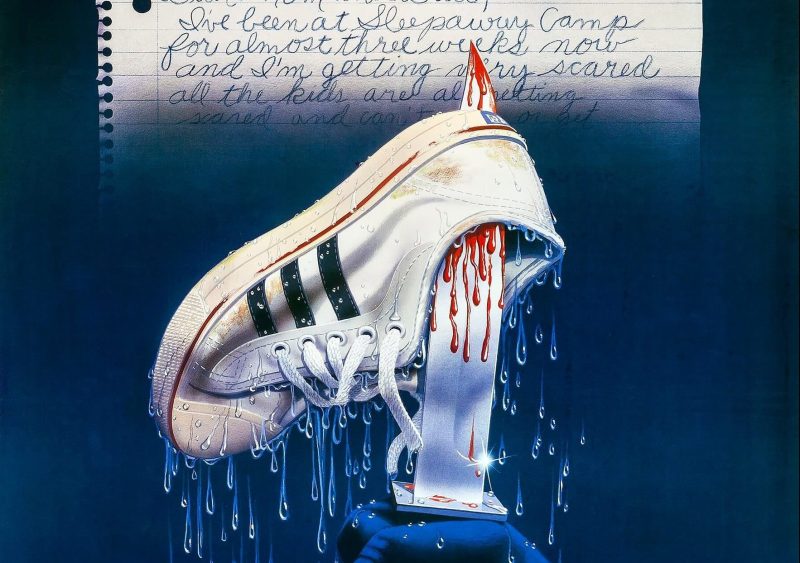

Stage Fright aka Aquarius aka Sound Stage Massacre aka… Bloody Bird?! As literal as that last title may be in relation to Michelle Soavi’s surrealist take on the tried and tested slasher villain, as was often the case with the kind of gore-laden European horror that found its way onto US shores during the infamously dead-eyed 80s, it is strikingly absurd — a cute reflection of the movie itself.

Stage Fright was produced by schlock guru Joe D’Amato, a director/cinematographer who pushed every exploitation button imaginable in a career that saw him direct and co-direct more than 200 movies, low-budget post-apocalyptic flicks such as Endgame (Bronx Lotta Finale) and controversial ‘Video Nasties’ Absurd and Antropophagus proving his commercial bread and butter. Absurd was also subjected to a plethora of titles as the filmmaker looked to market his product overseas: Rosso Sangue, Anthropophagous 2, Monster Hunter Horrible, The Grim Reaper 2, and in order to try to present the movie as a sequel to the Zombi series, Zombie 6: Monster Hunter. It should be noted that Absurd is also a slasher flick.

Another familiar face involved with Stage Fright is D’Amato go-to writer/actor George Eastman, here adopting one of an abundance of pseudonyms in the role of screenwriter, but the movie is a far cry from nihilistic affairs such as Absurd, favouring technical panache and visual storytelling over blunt, systematically controversial violence (though it isn’t afraid to go there either). In fact, if you’re able to appreciate its knowingly overblown, metaphysical fancies, Stage Fright strikes the perfect balance between artistic endeavour and blood and guts slaughter, beaming with the colourful allure of a dayglo Argento.

It should come as no surprise that first-time director Michele Soavi was the one-time protégé of Dario Argento, nor should it shock you to discover that Soavi acted as assistant director on the sublime giallo/slasher Tenebrae, as well as the cavalier but hugely charming Phenomena, a movie which shares some of Stage Fright‘s erratic tendencies. He would also act as second unit director on the notoriously explicit Opera, another performance-based giallo released the same year. What we have in Stage Fright is an audacious, broadly appealing crossover which sees the giallo and its bastard offspring, the slasher, meld together to create a cacophony of brutal murder, beguiling imagery and the kind of colourful unreality popularized by Mario Bava and mastered by Argento.

Such a tone is achieved by blurring the lines between fiction and reality, giving us a performance within a performance. Much like Lamberto Bava’s rampant gorefest Demons, a film which acted as an affront to censorship by painting a gross picture of distinct unreality, the movie rides that tenuous line in-between, and in doing so unleashes all kinds of madness. The horror-through-appliances sub-genre staked a claim during the 80s, the precipice of a new digital age inspiring an array of technophobe horror from Poltergeist to Videodrome. Here, the lines are blurred in a more traditional way, the screen becoming the stage, the supernatural giving way to the tangibly illusive.

The story is a familiar one: an escaped mental patient stalks a modern dance troupe who, under the tutelage of their demanding director, are preparing for opening night. It’s basically Michael Myers in a giant owl mask stalking a cast of underdeveloped and horrifically dubbed characters, but the storytelling is all in the visuals, the dialogue never less than witty and self-referential. The movie often resembles an acrylic painting sprinkled with the neon, cocaine dreams of the MTV generation — perhaps a by-product of Soavi’s time as a pop promo director for Bill Wyman of The Rolling Stones. Stage Fright is both erudite and vacuous, cheap yet blessed with instances of aesthetic wealth. It is full of contradictions.

Italian award-winning documentary filmmaker Barbara Cupisti plays the movie’s final girl, Alicia, her natural grace only emphasising the film’s dreamy aesthetics. Visually, it’s all very Argento, drenched in primary swathes and packed-full of technical prowess (there is even a moment in which one of the movie’s characters bows before a mirror to reveal another standing directly behind in a transparent nod to Tenebrae), but a lack of mystery and an abattoir of blunt and brutal deaths puts the movie very much in slasher territory. It’s an interesting hybrid — one of the most effective I’ve seen despite the movie’s obvious budgetary restrictions. The film’s unique mood is further driven by a wonderfully eclectic score that is one part pop fantasy, one part ethereal synth nightmare. Its sound design will stay with you long after the credits roll.

Once our cast become trapped in the theatre, which acts as our killer’s claustrophobic hunting ground, the line between fiction and reality is all but erased. Particularly inspired is a scene in which an actress is attacked by a masked individual who appears to be the show’s fictional killer. The impatient director urges the man to attack, and eventually he responds, only the throttling gets a little too rough, the repeated stabbing just a smidgen too real. It is the uncertainty, rather than the act itself, that proves unsettling, providing a lawless canvas that’s just waiting to be Jackson Pollocked.

This is one of a host of self-reflexive moments that puts the movie firmly in the realms of dreamlike fantasy, one that allows us to bask in Stage Fright‘s technical expertise and enjoy events on a level beyond our suspension of disbelief. Despite its cheapo veneer it’s all rather cerebral, expertly dissecting the boundaries between filmmaker and audience, between fiction and reality. “All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players.” I never imagined myself quoting Shakespeare when reviewing what is essentially a sordid splatter flick, and rarely have those words been used so literally, but here we are.

The movie’s finale is equally potty, featuring a veritable mausoleum of victims lined-up and positioned like mannequins in a boutique window, our thoroughly satisfied bird-man basking in his psychotic handywork. It is somewhat reminiscent of a scene in madcap Canadian slasher Happy Birthday To Me, one that sees former Little House On the Prairie princess Melissa Sue Anderson arrange the corpses of her victims around a dinner table as she attempts to get the deeply macabre birthday celebrations off with a bang, but the often inspired visuals never allow affairs to become so grim in Soavi’s airy nightmare. Beyond the madness and startlingly vicious acts of violence it’s the snow white blizzard of feathers and strains of classical music that stay long in the memory, along with a killer whose very disguise belongs in the rich tapestry of a surrealist painting. By incorporating the lowbrow traditions of the slasher genre, Stage Fright manages to uncover art where you don’t expect to find it.

Ultimately, the movie is one that you experience. Its setting is more than just a cute plot device. You often feel like you’re sitting in the front row of a real-life theatre, drenched in the movie’s striking colour palette as if burning under the intense glow of the coliseum spotlight. It is lavish and exuberant and often elegant, but dressed in enough butchery and debauch to fulfil the lusts of those unconcerned with such delicacies. It also features some truly divine photography and a sense of visual wit that would provide a creative shot in the arm for the flailing slasher genre, which by 1987 was stumbling towards temporary obsolescence, the tween-led antics of the once fearsome Fred Krueger nailing the coffin shut by the decade’s end. Soavi may be more synonymous with subsequent features Cemetery Man and The Church, movies that would almost single-handedly continue the traditions of Italian horror during the barren 90s, but this underseen, late-80s slasher should not be overlooked.

Bird of Prey

Stage Fright isn’t afraid to embrace the bloody extremities with a series of kills that will please slasher fans no end.

Cornered by our marauding killer, demanding director Peter (David Brandon) has his arm unceremoniously chainsawed off but is momentarily relieved to see the weapon’s motor cut fortuitously dead.

His unlikely reprieve comes in the form of a nearby axe, but our owl-headed purveyor of death is quicker on the draw, swinging the implement and chopping his latest victim’s head clean off his shoulders.

Ouch!

Holy Feathered Grace

Asides from the obvious gallery of deaths presided over by our killer during the movie’s hyper-tense, out-there finale, there are several moments of inspired visual composition to indulge in too.

Perhaps my favourite comes during that same finale, when a crouching Alicia (Barbara Cupisti), hiding beneath that very stage, listens tentatively while a blizzard of feathers showers her graceful form.

Truly gorgeous.

Choice Dialogue

In a cute nod to censorship hysteria and the cynical ways of the slasher, the always unscrupulous Peter has no qualms about shooting from the hip when challenged on the spurious content of his production.

Ferrari: I don’t see what the business of the victim seducing the killer has to do with anything.

Peter: All right, it doesn’t have anything to do with anything. But can you imagine the effect on the public? The victim rapes her own murderer. It’ll be sensational.

A heady blend of cynical slasher and giallo elegance,

Edison Smithdrips with visual splendour, reminding us of the then flailing sub-genre’s true potential. A delirious concerto of grandiose horror with the wit and technical bravura to match.