Checking in with Chuck Russell’s franchise-reviving practical effects spectacle

In hindsight, the third instalment of the A Nightmare on Elm Street series did as much bad as it did good. It raised the bar for practical effects artistry, re-embracing the conceptual motif that made Wes Craven’s original such a refreshing twist on the creatively moribund slasher. It also transformed Robert Englund’s Fred Krueger, now exclusively referred to by the much more familiar name ‘Freddy’, into a child-friendly rock star, leading the franchise along commercial avenues from which, at least creatively speaking, it would never fully recover. When Krueger emerges from the TV set at the Westin Hills psychiatric unit and utters the immortal line, ‘Welcome to prime, bitch!,’ a quip that was ad–libbed by an actor who lived and breathed the character, he may as well be referring to himself. He could also have been giving something of a meta shout-out to indie production company New Line Cinema, who would become such bona fide Hollywood players after the character’s original run that they were later dubbed ‘the house that Freddy built.’

It almost didn’t happen for New Line honcho Robert Shaye, who initially took a punt on a game-changing screenplay that had been passed on several times as the oversaturated slasher genre became synonymous with a period of censorship hysteria, an era of moral outrage commercially derailing genre peer Jason Voorhees as horror’s surest bet. The original A Nightmare on Elm Street was plenty violent, Craven pushing the horror to mind-bending extremes thanks to a concept with a seemingly endless canvas, but crucially it veered towards the supernatural, Freddy’s frazzled visage something of a throwback to the Universal monsters of yore. That fantasy element allowed the film to swerve the censors somewhat, and Shaye knew he was onto a winner commercially, but Craven always envisaged A Nightmare on Elm Street as a one-shot deal. The two would settle on a sequel-setting ending that many feel tarnished the film’s overall presentation, but Craven, whose first big studio movie Deadly Friend was tampered with to capitalise on Krueger’s immediate popularity, wanted no part of 1985’s Freddy’s Revenge. Like John Carpenter before him, he wanted to branch out rather than fall into the financially sweet but creatively stale realms of horror franchise.

Enter Alone in the Dark director Jack Sholder, who was more than happy to light the taper on New Line’s cultural powder keg. Freddy’s Revenge, which has garnered a huge cult following in the years since its release, certainly has its charms. There’s the fantastic lead performance of actor Mark Patton, ‘final boy’ Jesse Walsh proving one of the strongest protagonists in the slasher pantheon. Krueger himself has arguably never looked more terrifying, his borderline-feral make-up a truly gruesome sight, and Englund really begins to find his feet as the “bastard son of 100 maniacs”, further refining the nuances that made the character so fresh and unique.

Freddy’s Revenge also features one of the most eye-watering instances of practical effects wizardry in the series courtesy of Kevin Yagher and his team, Krueger shedding Jesse’s skin like a silk gown before downing Robert Rusler’s immensely watchable Grady ― a glimpse at the increasingly elaborate visuals that would follow. Then there’s the subject of the movie’s controversial gay subtext, something that was flat-out denied for many years by director Jack Sholder and writer David Chaskin, presumably due to the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s and the stigma it created in Hollywood circles. All-in-all, an interesting movie, whatever you may think of it critically.

Freddy’s Revenge also managed to rob its predecessor of its groundbreaking concept, ditching the refreshing dreamworld angle for a straight-up possession story that tread more familiar ground. A by-product of its conceptual digression, the sequel would also rob Krueger of Charles Bernstein’s iconic theme, a scathing lullaby of chimerical highs and gut-wrenching lows that sinks to the pit of your stomach. Future Hellraiser composer Christopher Young did a fine job in his own right, but few themes represent the essence of a character quite like Bernstein’s. For many, separating the two was borderline-sacrilegious. Amazingly, the penny-pinching New Line, who figured any bozo in a mask could play Krueger, even ditched the legendary Robert Englund for a mercifully short-lived replacement, quickly reneging after realising that without the actor there was no sequel. Freddy’s Revenge did great numbers at the box office, thanks in large part to the success of the original, but it left the series in a kind of creative limbo. As ‘Dream Warriors’ director Chuck Russel would explain in a 2017 interview with Bloody Disgusting, “The studio rightfully felt that Nightmare 2 was a bit of a misfire… At that point, they were uncertain [the series] would continue. I thought in Nightmare 2 Freddy became almost less personable… more of a typical slasher than a dream demon.”

Ain’t gonna dream no more, no more. Ain’t gonna dream no more. All night long I sing this song. Ain’t gonna dream no more.

Roland Kincaid

By 1986, Craven was champing at the bit to be involved with a second sequel as he looked to rescue the Krueger character and end the series the right way. Ironically, Craven’s original idea was to have Krueger cross over into ‘reality’ and stalk the cast of the original film, a meta-infused pitch that New Line, at least for the time being, rejected. Almost a decade later that concept would come to fruition thanks to Scream progenitor Wes Craven’s New Nightmare, a film that was lost on audiences less than three years after Shaye had run the series into the ground in favour of jumping the shark and securing his company’s financial future. New Nightmare may have been too much too soon, but the film would garner plaudits years later, skilfully undoing the mystique-crushing antics of those later sequels and once again making Krueger a serious threat.

Similarly, Craven’s original script for The Dream Warriors was much darker, something more in line with the original A Nightmare on Elm Street. Other ideas were duly passed around. Actor John Saxon wrote a treatment for a prequel called ‘How the A Nightmare on Elm Street All Began’ (surely a working title) that revealed Freddy’s innocence à la 2010’s pitiful reboot, his supposed misdeeds actually committed by the Manson Family. Robert Englund also wrote a treatment titled ‘Freddy’s Funhouse’ with Tina Gray’s older sister as the protagonist, part of which was used for the pilot of TV spin-off series Freddy’s Nightmares. Luckily, New Line and director Chuck Russell saw things differently.

It’s amazing that Freddy’s Revenge embraced such a tonal digression off the back of the original film’s success, but Russell was determined to set things straight, and with Craven back on board as co-writer the script was in good hands, those mind-bending delineations between dreams and reality once again at the forefront. Learning from the mistakes of his predecessor, Russell decided to embrace the unpredictable realms of the subconscious and then some, producing a movie that, while very much engaged in the realms of fantasy, stayed true to its internal logic. Craven’s original sleight of hand slasher had teased the creative possibilities with skill, wit and resourcefulness, Krueger’s form pushing through a latex wall above Nancy’s bed and a rotating room for Tina’s ceiling-bound slashing just two of several ingenious visuals that set the film apart. With the field of practical effects becoming increasingly sophisticated and the dream concept still relatively untouched in terms of what was possible, The Dream Warriors was an unusually exciting prospect as third instalments go.

Speaking on the wonderful franchise documentary Never Sleep Again: The Elm Street Legacy, Russell would relay his intentions in no uncertain terms, “The original script for ‘Elm Street 3’ was darker and actually profane. I think Wes was trying to take it in an even more horrific place, and I was more interested in the imaginative elements of the piece.” Fortunately for Russell, he was able to convince the money men that his way was the way forward. “I convinced New Line we could do bigger, wilder dream sequences and make Freddy more of a devilish ring master… make it both more frightening and more fun. I was interested in going deeper into the imagination of the characters and I saw the potential to get Freddy talking and literally morphing in fantastic ways in the different dream scenarios. I felt I could keep it scary but infuse a dark humour that Freddy had the potential for… and I knew Robert England could handle it. That element of bringing Freddy into a full characterisation had New Line concerned, but they let me run with it. They took a chance on my vision.”

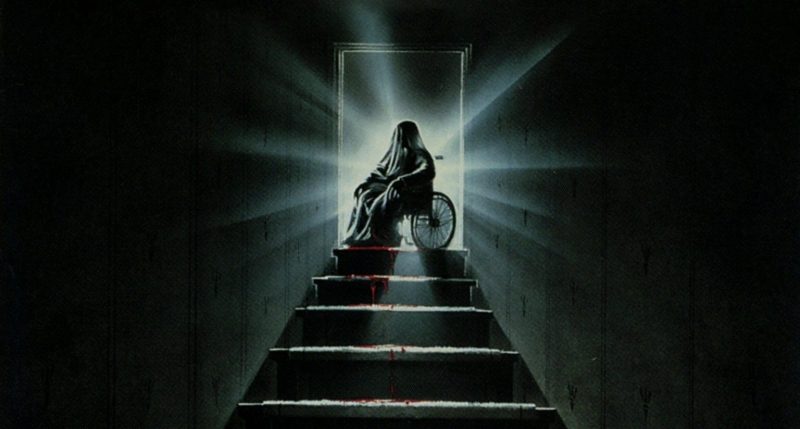

From a visual perspective The Dream Warriors doesn’t disappoint. Protagonist Kristen Parker (an 18-year-old Patricia Arquette in her debut role) leads us wandering through Krueger’s ethereal funhouse in spectacular fashion, 1428 Elm Street acting, as Craven himself would put it, as “an architectural portal” into Freddy’s dreamscape. Art directors C.J. and Mick Strawn work wonders alongside set decorator James R. Barrows in making Krueger larger than life, transforming the character into a veritable circus master who is capable of adopting multiple forms, hunting his prey in the guise of a sexy nurse with an incredibly skilled tongue, a vicious puppet-come-malevolent puppeteer, and in one of the film’s most audacious set-pieces, a giant ‘Freddy worm’ that attempts to swallow poor Kristen whole. While the first two movies saw Krueger invade the suburban fringes, his influence slowly bleeding into reality, the kids of Westin Hills, outcasts in the real world, are invited to explore the recesses of the character’s twisted imagination. Thanks to SFX artist Peter Chesney and his crew, it’s jaw-dropping stuff at times, even by today’s standards.

Of course, as proven by the entrenched in formula A Nightmare on Elm Street 4: The Dream Master, visuals aren’t everything. They’re a fantastic commercial draw but we still need characters who are more than just fodder for a series of heavily-staged set-pieces that determine the action. While ‘Dream Master’ director Renny Harlin consciously made Krueger the film’s hero and pantomime villain, his box-fresh cast deflatingly one-dimensional, Craven and Bruce Wagner’s screenplay, further refined following a late Chuck Russell and Frank Darabont re-write, gives us a cast of relatable characters who prove the perfect targets for Krueger’s twisted antics. The teenage cast of The Dream Warriors are billed as the ‘last of the Elm Street children’, the very same whose parents burned Freddy to death for his perverted misdeeds. This gives Englund’s fritter-faced miscreant a sense of vengeful purpose that was lacking in Freddy’s Revenge, returning to the original film’s narrative and everything that it stood for.

Vital to the film’s retrospective approach is the addition of two legacy characters, particularly the re-casting of original final girl Heather Langenkamp as Nancy, here returning as an intern therapist and dream specialist wielding the kind of radical answers that threaten to alienate both her and love interest Dr. Gordon (Body Double‘s Craig Wasson). B-movie icon John Saxon also returns for the inevitable non-meta swansong (see New Nightmare for that particular delight), his death scene and a plot development involving Freddy’s bones embracing the spirit of Jason and the Argonauts in seriously camp fashion, but his brief appearance as a broken-down alcoholic living with the stench of regret proves far less integral. Conversely, Langenkamp is once again central. The original final girl of the series, Nancy was a heroine we could all get behind, and if you count the tacked-on false ending of the first movie, she and Krueger still had some unfinished business to attend to.

[pointing to Kristen’s model] I used to live in this house.

Nancy Thompson

Nancy wasn’t your typical, run-of-the-mill slasher heroine. She was steely, resourceful, erudite; perhaps second only to Jamie Lee Curtis as the sub-genre’s most iconic conqueror, and in many ways more formidable since the odds were stacked so heavily against her. Nancy had defeated Krueger once, understood his cackling brand of sadism and the torment of those he pursued better than any living person. If anyone could put him down for good, it was her. Many see Freddy’s Revenge as a series oddity that can be enjoyed as a standalone feature outside of the franchise mythology, an outsider that didn’t exactly feel like a traditional Nightmare instalment. That’s understandable since the film was left out in the cold by those later sequels, but if one ingredient was decisive in giving the series back its identity it was the returning Langenkamp, and the same can be said of New Nightmare. Craven knew the importance of Nancy to his vision. Freddy is undoubtedly the main attraction, but every dastardly supervillain needs a worthy foil, and Langenkamp, marred by a cosmetic grey streak and convincingly matured only three years on from her original performance, is as good as it gets.

For fans of the original film, it was nice to see Freddy and co return to their narrative origins, even if Freddy’s Revenge vaguely touched upon the events of A Nightmare on Elm Street via Nancy’s dubiously left behind diary. Back in 1984, Robert Englund’s most famous creation changed the way we looked at slasher villains. Far from the seek and destroy barbarian audiences were used to, for him the thrill was in the foreplay, the character literally drawing his power from the sense of fear his dream world antics instilled. He was more cerebral than the likes of Jason Voorhees, flaunting his otherworldly powers in the most manipulative of ways. In the original instalment he framed delinquent-with-a-heart Rod for the murder of Tina. In Freddy’s Revenge he literally put the glove on Jesse’s hand as he set about possessing his Earthly incubator. The Dream Warriors sees Freddy let loose on a teen psychiatric ward, the ideal stomping ground for a sadistic malefactor who preys on weakness as a means to gain strength. The film’s opening moments result in Kristen being shipped off to Westin Hills following a supposedly self-inflicted wrist slashing, but if you believe Freddy isn’t the culprit I’ve got a filthy striped sweater to sell you.

Unfortunately for Krueger, Kristen has the power to draw others into her dreams, which levels up the playing field somewhat, especially as each patient acquires a special ability that belies their real-world weakness. As well as her group-uniting abilities, Kristen develops incredible gymnastics skills that leave Freddy physically impotent, and our villain’s troubles are only just beginning. Ken Sagoes’ short-tempered ruffian Roland Kincaid develops heroic physical strength; mute Joey Crusal is given the rather fitting gift of a supersonic scream; as well as being able to walk, paraplegic and geek outsider Will Stanton acquires magical abilities relating to his favourite Tabletop RPG, The Wizard Master, and reclusive former drug addict Taryn becomes a super confident, switchblade-wielding badass. Nancy even flaunts her ability to pull objects out of dreams, something first realised in the original movie. This results in a series of suitably ironic deaths that transform Freddy into a wisecracking antihero in the Schwarzenegger mode that would set the template going forward, though such a formula would be watered down to a thin gruel by the turn of the 90s. The irony of Freddy tying a sexually repressed mute to a bed using tongues is a hoot, as is the quite ludicrous image of our killer symbolically ejaculating while injecting Taryn with syringe-tipped gloves. It is completely absurd, even a little perverted, but it works a treat. When it comes to dream psychology and gallows humour, The Dream Warriors is a cut above all that it would ultimately inspire.

It is from this sub-narrative that The Dream Warriors is able to draw its true strength. While the original movie successfully examined the mind-bending slights of the subconscious, Russell’s visually audacious outing goes above and beyond, maintaining those universal properties while exploring the vast and endless possibilities of a domain in which the laws of traditional physics no longer apply. In A Nightmare on Elm Street, Craven smartly tapped into those universal ambiguities that we’ve all experienced while inhabiting the realms of the subconscious mind: our inability to escape a pursuing menace or find our way out of a seemingly familiar place, sudden changes in identity and our incapacity to delineate the dream world from reality to name but a few. It may lack the dead-on dream psychology of Craven’s original, but thanks to its gorgeous set design, some audaciously realised SFX magic and a spellbinding 80s colour palette, Russell creates an environment where absolutely anything goes, forging a visual realm that is truly fantastical.

As wonderfully as the plan is executed, there is a downside, the film proving somewhat problematic for fans of Krueger’s short-lived darker incarnation. Englund is nothing short of brilliant, approaching the material’s particular brand of comedic sadism with a devilish relish that’s impossible to resist, but the mostly comic book presentation and commercially calculated characters step out of the darkness in favour of the horror-sappingly fanciful as the film wears on, Krueger caught between teenage pinup and ruthless child killer in a way that can be tonally confusing. The opening scenes, including Kristen’s so-called suicide attempt and puppeteer Phillip’s vein-ridden slashing err on the darker side, but overall it’s clear where the series is heading. Compared to those later sequels, which completely neglected the horror for increasingly asinine wisecracks and commercial gimmickry, The Dream Warriors is a veritable masterwork, retaining just enough darkness to remind us exactly who it is we’re dealing with, but the writing is on the wall in big bright lights, a tone solidified by the use of title track performing American hair band Dokken. It was an inspired commercial move to target the MTV crowd, but if you’re looking for a more traditional horror experience you’re better off sticking with the original A Nightmare on Elm Street, New Nightmare or even Freddy’s Revenge. There are unsettling moments in The Dream Master, but the horror is often secondary.

The Dream Warriors also wanders into sequalitis territory like a sleepwalking teen ripe for the slaughter. Krueger’s credibility would plummet after 1989’s The Dream Child and 1991’s desperate 3-D debacle Freddy’s Dead: The Final Nightmare, the character lampooning everything from The Wizard of Oz to Road Runner in New Line’s relentless pursuit of puerile comedy, but it was those pesky backstories that truly tarnished the character’s sense of mystique, and it all began with The Dream Warriors. The film may stop short of The Final Nightmare‘s revelation that Krueger once fathered a child, but it commits the same crime suffered by the Halloween series and countless other horror franchises, adding convoluted origins stories to characters who work best as mysterious supernatural entities. Here we discover that Krueger’s mother gave birth after being accidentally locked in a room with a gaggle of mental patients who repeatedly raped her, a heavy-handed, almost laughable sub-narrative that threatens to derail the whole movie. The fact that Krueger’s child killer and implied paedophile was burnt at the proverbial stake was all that was required. The less we know about a miscreant of his variety for the purposes of mainstream entertainment the better.

Elsewhere, events can be curiously light-hearted and openly playful, particularly during a gallows humour fantasy segment involving Dick Cavett and Zsa Zsa Gabor that would pave the way for future comedic cameos from the likes of Alice Cooper and Tom and Roseanne Arnold, who would all grab an undeserved ride on the Fred Krueger gravy train as the series chased the ever-dulling flicker of creative aspiration (Johnny Depp gets a pass for obvious reasons). It’s a startling indication of the crippling celebrity highs that the character would soon reach, Englund’s ever-priceless theatricalities marred by New Line’s relentless, youth-oriented pantomime, but for a brief period The Dream Warriors breathed new life into the series both creatively and commercially, the instalment’s mega fandom unsurprising and largely deserved. Krueger fans tend to fall into two categories: those who appreciate his darker incarnation and those who embrace the whimsical antics of those later sequels. Of all the movies in the franchise, The Dream Warriors strikes the fairest balance between the two, which is perhaps why it proves somewhat divisive between diehards who are typically all or nothing.

What’s wrong, Joey? Feeling tonugue-tied?

Freddy Krueger

While the original A Nightmare on Elm Street announced Krueger as horror’s latest conceptual player, The Dream Warriors, which managed a whopping $44,800,000 on a budget of only $4,600,000 in the US, transformed him into a global megastar. By the time The Dream Master came to fruition, he was far and away the genre’s hottest property, the now flourishing New Line even backing out of the chance to take part in a potentially money-spinning Freddy vs Jason crossover with former kings of the slasher sub-genre Paramount Pictures, whose own horror attraction Jason Voorhees was experiencing something of a downturn in popularity. While the Carrie-inspired Friday the 13th Part VII: The New Blood floundered at the box office, The Dream Master became the most successful instalment to date, raking in $49,369,899 from an estimated $13,000,000 in the US — unheard of numbers for a slasher movie during the late 1980s. New Line had taken Russell’s vision and run with it, and for a brief, hyperbolic period of unabashed commercialism, it continued to bear fruit.

But such monumental success can create its own problems, and the more comedy-driven Freddy that The Dream Warriors helped spawn would catch on like wildfire, especially with the kids, an irony that wasn’t lost on those who were less than enamoured with the character’s almost universal influence. Soon Krueger was making guest appearances on TV shows, embracing more commercial tie-ins, performing absurd rap songs in an attempt to appeal to more calculated demographics. New Line would also lend the Krueger name to a whole bunch of crappy merchandise aimed primarily at children, something that would lead to protests from religious groups, who would describe one particular doll as, “the product of a sick mind,” further opining, “The fact that a major toy manufacturer would promote this doll is tragic”.

With their futures at stake and a less-than-secure financial history, you couldn’t blame New Line for indulging in their newly discovered mascot, but there’s no doubting the fact that Russell’s commercially astute instalment jeopardised the integrity of the franchise going forward. While The Dream Warriors trod a comparatively delicate line between horror and fantasy, later instalments would shed creative perspective like a Freddy-shaped shuttle hurtling towards the sweltering shores of hyper-commercialisation. The Dream Master would lay waste to the survivors of Westin Hills within the first ten minutes of the movie, replacing them with a cast of paper-thin characters who took a backseat to Freddy’s increasingly ludicrous, horror-defying antics, and by the time the series had entered the barren 90s, one of the genre’s most reprehensible creations had become little more than a commercial sideshow, flogging his increasingly tired act like a circus bear being poked and prodded by the very kids that his character had supposedly molested. When it comes to commercialism, there really is no sense of decency it seems.

The Dreams Warriors is by no means perfect, but for all its plot distractions and future crimes, it touches a unique sweet spot that for many fans of the franchise has never been bettered. It may swerve the darkness in a way that displeased many more, but Russell’s franchise-reviving vision was an audacious and highly effective exercise in imagination that expanded on the original movie’s concept while staying true to the staple ingredients that made Krueger such a deliciously unique character. Though it pales next to Craven’s opus as an exercise in terror, it both redesigns and rediscovers, which is as much as you can hope for from any sequel, its largely rotten legacy further testament to its profound influence on one of horror’s most universally recognised characters.

Director: Chuck Russell

Screenplay: Wes Craven,

Bruce Wagner,

Frank Darabont &

Chuck Russell

Music: Angelo Badalamenti

Cinematography: Roy H. Wagner

Editing: Terry Stokes &

Chuck Weiss