Fred Krueger embraces the realms of celebrity, but at what cost?

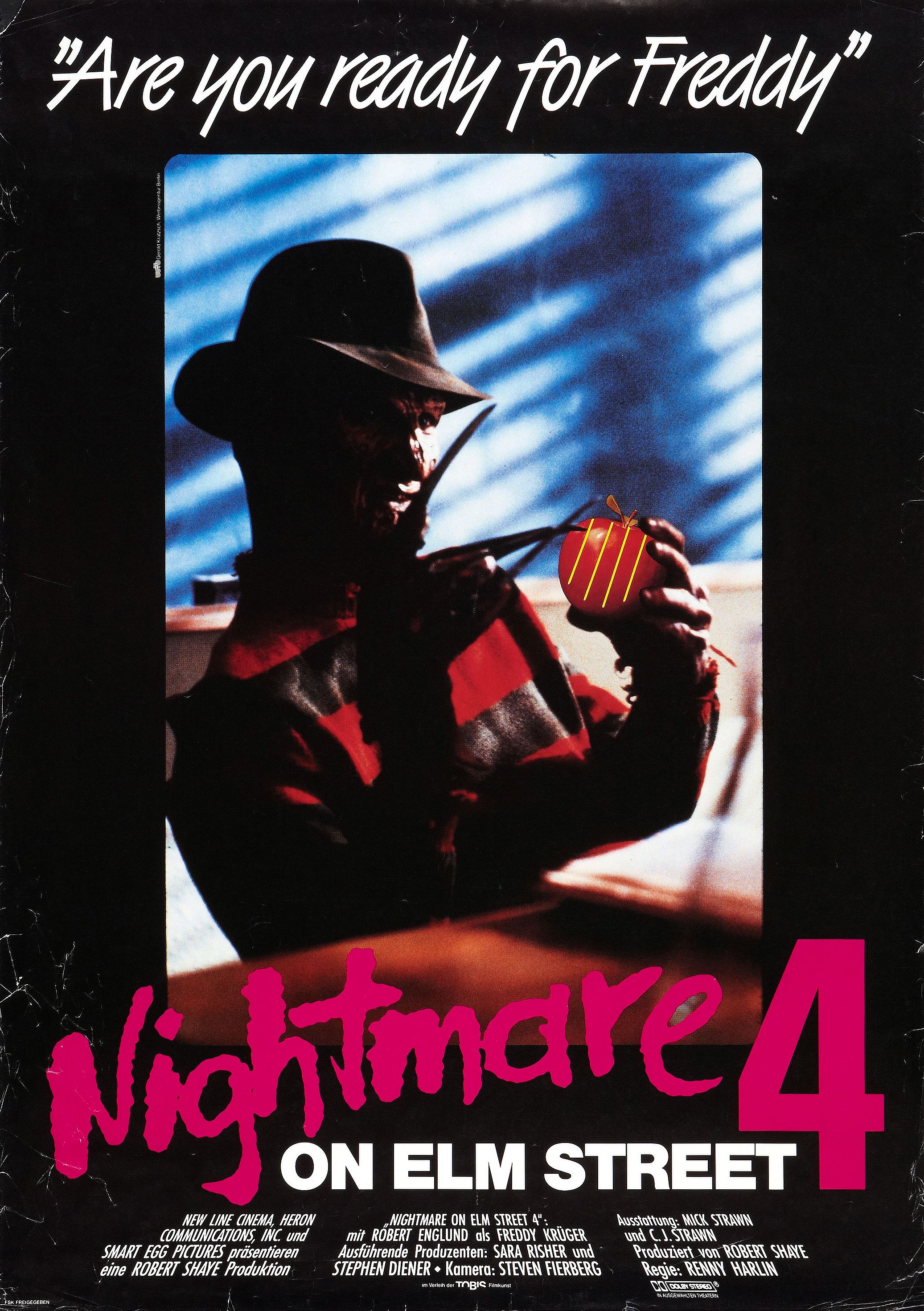

New Line’s Cinema’s fourth instalment of the A Nightmare on Elm Street franchise is the one that many fans remember fondest. Thirtysomethings cherish this movie like a precious childhood toy, a dead-on irony that will soon become apparent. Though I feel rather differently, it comes as no surprise. Freddy fever exploded in a powder keg of hypercommercialism following The Dream Master‘s much anticipated release in the summer of ’88, our once-wicked killer transformed into the kind of pop culture phenomenon that was unprecedented in the realms of mainstream horror.

Late-80s Freddy was a truly postmodern creation who crossed ethical boundaries in ways fans could never have envisaged just four years prior. Back when Krueger first emerged from the shifting shadows of A Nightmare on Elm Street‘s opening boiler room salvo, the slasher movie was marketed exclusively at older teenagers, taking a familiar setting ― summer camp, high school, everyday suburbia ― a masked killer with a unique weapon, and a cast of hormone-fuelled characters that older kids could relate to. And there was usually blood to be had. Lots of it.

Censorship hysteria brought an end to all of that, so much that by the late-1980s horror was no longer a sure thing for indie producers looking to turn a profit. Slashers had thrived on blood and guts notoriety, on the whole had little else to offer. When creative violence was left to sluice through the cutting room floor like so much rotten flesh, filmmakers were left with two choices: they could carry on making cold-hearted slashers, knowing their vision would be jeopardised almost completely, or they could turn to the supernatural, crank up the self-aware humour and sidestep the censors. No character represented that tonal shift quite like Krueger, the immoral poster boy for a generation of horror-obsessed tykes.

I remember acting out scenes from The Dream Master on the school playground, particularly the film’s infamous karate scene, which for reasons that will become clear was the most practical scene to imitate. One of my friends had a replica glove with plastic blades, and we would tussle for a turn in the 30 minutes of playtime allotted, our imaginations alive with visions of sadistic murder. So enthusiastic were we about portraying our unlikely hero that sometimes fights would break out. We were seven years old at the time. Just imagine what those teachers, weaned on horror of the more traditional variety, were thinking. Back then, kids were scared of rubber bats.

The A Nightmare on Elm Street films were never slashers in the purest sense, their supernatural persuasion making them immune to the necessity for realistic violence. In fact, by the end of its original run the franchise barely resembled horror, taking on an almost fairy tale façade. The story of a notorious child killer burnt at the proverbial stake by a mob of vengeful parents, the series would rely on the kind of concept that allowed Krueger a devilish edge ― the ability to pick-off his persecutors’ kids in the one place they couldn’t protect them: their dreams. It was a deceptively simple, yet groundbreaking deviation brought to life with dazzling ingenuity by creator Wes Craven, the film’s popularity, coupled with the promise of increased budgets down the road, offering endless possibilities going forward.

Wanna suck face?

Freddy Krueger

There was a stumbling block: 1985’s Freddy’s Revenge, which took the baffling step of ditching a concept that had wowed audiences only a year earlier, settling on a straight-up possession story that touched on themes of homosexuality during an AIDS epidemic that saw it criticised in many corners. The film still did great numbers at the box office, based largely on the success of its predecessor, but New Line Cinema were on the verge of scrapping the series before it had even got going.

All of that changed when director Chuck Russell got his hands on the property two years later, convincing executives to flesh-out the Krueger character and his ethereal stomping ground, leading to a series of practical effects set-pieces that altered the direction of the franchise and its star attraction forever. This was a more playful Krueger, still relatively dark and motivated by cruelty, but more in the wisecracking action mode, the iconic line, “Welcome to prime time, bitch,” a self-fulfilling prophecy that saw the character catch on like a particularly nasty boiler room fire. It’s no coincidence that The Dream Master was the first film in the franchise in which Robert Englund received top billing. The movie was so successful it would even inspire a two-season TV show hosted by Krueger called Freddy’s Nightmares, a role the actor typically relished in.

It’s hard to convey just how popular Krueger was back in 1988, though horror fans who lived it will remember all too well. At six I was already a Freddy fanatic suckling at the teat of the Krueger merchandise machine, and for a short time The Dream Master was my absolute favourite movie in the whole world. The set design and practical effects were like nothing I’d seen before, a fanciful, kaleidoscopic experience that scorched the collective imagination, playing out like a Lewis Carrol novel dunked in 80s decadence. I lapped up the character’s comedic repertoire, which was the height of wit to a boy so young. When kids were imitating Robert Englund’s most celebrated character, they weren’t trying to scare people. He was no longer the villain beset on gruesome murder sprees, notions of paedophilia all but suppressed.

Freddy (not Fred as he was originally named) was like an amusing chum, a glorified stand-up act reeling off one-liners like Arnold Schwarzenegger at his most self-aware. You wanted to be him, not flee him, and according to Harlin, that was the intention all along. “At this point ― the fourth movie in the series ― people who have been watching the films know, basically, the rules of the game at this point,” Harlin would explain. “It’s hard to scare them with, you know, a surprise: Freddy comes around the corner. Wow! I felt that we had to make him the hero. He is like the good guy of the story ― in a way though, he’s the bad guy ― but he is kind of like the person we root for. He is Rambo. He is James Bond. And why I use James Bond as an example is, he was not only heroic but he was like… really cool. He’s like the guy who has the Martini and the cigarettes and the women. I wanted [Freddy] to be like the coolest guy there is.”

For me, Freddy was the coolest, more so since the series was savvy enough to tap into the MTV market, transforming Krueger into a mainstream celebrity and certified rock star who transcended the horror genre with his fanciful presentation. The Dream Warriors had already recruited American metal band Dokken to perform the film’s theme song a year prior, and The Dream Master soundtrack took it to the next level, adding a whole host of pop star royalty, including the movie’s very own Tuesday Knight, who as well as replacing Patricia Arquette as the returning Kristen in a classic soap opera switch would also perform the film’s title song ‘Nightmare’. Ceaseless TV appearances and celebrity tie-ins increased Freddy’s stock no end. The bubble would quickly burst but the character had never been so relevant. When my generation thinks of Freddy Krueger, the majority think of The Dream Master, especially casual fans who were merely caught up in the character’s peak hype. The likes of Michael Myers and Jason Voorhees had both cleaned up at the box office at one time or another, but neither reached the commercial heights of Krueger in terms of international exposure. The guy was everywhere.

Former slasher kings Paramount certainly took notice, approaching New Line Cinema with the prospect of a Freddy vs Jason crossover, but the two parties couldn’t come to an agreement and the idea was shelved for an incredible fifteen years. Paramount may have been the major studio to New Line’s indie production minnow, and it must have been tempting to take the bait, but while Jason was experiencing something of a downturn in popularity, Krueger was ascending to the commercial stratosphere. While Carrie knock-off Friday the 13th Part VII: The New Blood resulted in Paramount’s lowest returns to date ($19,170,001), The Dream Master became the most successful in the franchise, grossing a whopping $48,000,000, almost $5,000,000 more than its predecessor. Only a few years prior the original A Nightmare on Elm Street was rejected by almost every major studio in Hollywood. It was more than New Line could ever have hoped for.

All these years later, it all seems just a little dated; watching The Dream Master as an adult, it’s hard to imagine ever being so bedazzled by what is essentially a horror sitcom on a Hollywood budget. Many fans still regard The Dream Master as the pinnacle of the series, and not just from a commercial standpoint. There’s a huge element of nostalgia involved. Not only does the movie inspire warm memories of the character, Freddy was the first figurehead of the cultural marketing machine for many youngsters, and for some The Dream Master has all kinds of personal and collective connotations attached to it, from hit singles to favourite toys to friends and childhood experiences. Krueger was everywhere in 1988: on talks shows, in pop videos, mingling with celebrities like a horrifically scarred peewee Herman. He was also the subject of controversy from religious groups horrified by the fact that a child killer and implied paedophile was being so ruthlessly marketed towards the tween demographic, calling the release of a Krueger doll “the product of a sick mind” and “tragic”. Though we’ve since become desensitised to such cynical commercial endeavours, it’s hard to disagree.

There are still reasons to admire the fourth instalment of the hit franchise. Harlin took the Chuck Russell template and plunged headlong over the ravine, cranking up the humour and ditching the darker elements still prevalent in The Dream Warriors. Some of those set-pieces, though dominant in a way that detracts from pretty much every other aspect of the movie, are still mind-blowing, despite their often camp nature. The set-piece everyone remembers sees bugphobe Debbie (Brooke Theiss) transformed into a human cockroach and squished into a splat of sallow goo, one so brilliantly and expensively conceived that Harlin and co quickly exceeded their estimated $13,000,000 budget, an indicator of the film’s creative imbalance. This meant that other set-pieces had to be altered or culled entirely, with less time afforded to plot and characterisation. In creative terms, Krueger became a victim of his own success.

Thanks to Debbie’s bone-crunching, flesh-flopping demise, Rick, who was originally set to succumb to a runaway elevator, would instead take on an invisible Freddy in a farcical Karate showdown that is basically the horror equivalent of Die Another Day‘s Brosnan-crushing invisible car. The scene is incredibly lame, even more so for Freddy’s repertoire of cod-Oriental philosophies, but those moments that helped exceed budget more than make up for it, including a rather nifty Krueger resurrection and a chest-bursting finale that banishes the character to commercial purgatory for at least another year. There is also an inspired touch featuring a dream loop that taps into the uncontrollable nature of dreams by trapping two of the film’s characters while another heads for their grisly demise. As a reminder of the believable dreamworld delineations that set the original movie apart, it’s a nice touch worthy of Craven and his most enduring character.

The Dream Master placed such an emphasis on dreamy visuals due to a writers strike that saw parts of the script written immediately prior to shooting, and it shows. The film begins with the quickfire demise of the previous instalment’s survivors, making fickle fare of the surviving Dream Warriors, something that shocked actors Rodney Eastman (Joey) and Ken Sagoes (Kincaid), who understandably expected bigger roles upon their return. The two are quickly offed following a deeply disingenuous ‘reunion’ with Arquette replacement Knight, who was widely disliked on set due to a romantic fling with Harlin and the favouritism that went with it. Again, it shows. There is absolutely no chemistry between the three, no sentimental feelings of reunion for audiences to buy into. It’s all so hasty and fickle.

Welcome to Wonderland, Alice.

Freddy Krueger

The Dream Warriors are replaced by a cast of paper-thin characters who are almost impossible to invest in, many of whom holding no other purpose than to be lined up for the slaughter. That’s the kind of thing that’s expected from a bog standard slasher, but when you’re dealing with a character who preys on emotional weakness, the screenplay requires a little more meat on the bones if we’re to fully invest. Take Debbie’s death ― the movie’s money scene ― for instance. All we know about her character is that she’s scared of bugs. We know because she steps on a cockroach early on, but is this really enough for us to sympathise with her demise on any serious level? Pre-The Dream Master, the A Nightmare on Elm Street series had always given us richer, more conflicted characters in order to set Krueger apart as a monster who transcended your typical slasher villain. Craven’s original gave us a child of divorce living with the stink of her alcoholic mother, wild child Tina, bad apple Rod. Even Freddy’s Revenge, for all its indecisiveness, excelled at delivering a confused and alienated protagonist who the film’s antagonist could manipulate. The Dream Warriors went even further, giving us a whole cast of troubled kids for Freddy to tenderise on a psychological level. Barely a year on and the difference is palpable.

Harlin has already established that Freddy is The Dream Master‘s true protagonist, so the idea was clearly to move away from what the character had been traditionally, but if you’re going to turn the film’s monster into a hero, surely there has to be some kind of satisfaction taken from the deaths of his victims. We’re all aware of the unspoken rules of slasher movies (if not, watch Wes Craven’s delightfully self-reflexive Scream). You can’t drink, do drugs or have sex if you’re expected to survive a slasher. You also can’t be a bitch or a douchebag or screw anybody over. That’s why we’re able to root for Jason Voorhees as an antihero. His victims are usually rulebreakers or jerks or annoying, anything that makes their fate deserved. In The Dream Master there’s none of that. The characters are mostly good, likeable kids who don’t hurt anyone. The same can be said of previous Nightmare instalments, but with Freddy as the hero it no longer applies. It’s all so confusing. “I started storyboarding the dream sequences, sometimes without any kind of screenplay,” Harlin would recall, lamenting the film’s hectic production. “And a lot of the scenes kind of evolved during lunch breaks and morning hours and a lot of times we had no idea what we were gonna shoot. We knew that we have a scene about Alice being really scared. In her house. And something happens the next day. So we know that we will need a house and we’ll need Alice, but then we didn’t know anything else.” Maybe that explains it.

Despite Tuesday Knight’s preferential treatment, protagonist Alice is the movie’s most engaging character, a pallid introvert lost in her own private wonderland who daydreams about finding the strength to stand up to her ill-tempered father or make moves on “major league hunk” Dan (that line always tickled me). Thanks to her dead mother’s parting gift, a nursery rhyme about a fabled character who learned how to control dreams through positive visualisation, Alice is able to confront Freddy head-on, though our villain’s jovial antics and lack of scares make the movie’s finale just a little underwhelming, even with the lure of Freddy’s blockbuster demise. The rest of the film’s characters, asides from the previously established Joey and Kincaid, are vapid stereotypes, mere accessories to Freddy’s one-man carnival. If prancing, cackling Krueger is your bag, you’ll bask in this movie’s prankster opulence. Harlin has fun with The Dream Master, but oftentimes it needs reigning in.

Alice replaces Kristin as the movie’s final girl, who, having lost the power to draw people into her dreams at will, suddenly begins bringing them in against her will. Why she passes this now cursed ability over to Alice is anyone’s guess, but attempting to understand this movie’s fundamentals is an often fruitless endeavour. When Dan, attending new squeeze Alice’s brother’s funeral days after watching her best friend sucked to death in class, asks if she’s okay, you can only shake your head in disbelief. “Not really,” she replies without a hint of self-awareness. Thanks to Kristen’s incongruous parting gift, Alice soon begins drawing kids to their deaths left, right and centre. Freddy also develops a rather worrying penchant for fancy dress, assuming the guise of a nurse, a teacher, a surgeon, and even a pornographic model during the movie’s 90-minute running time, playing life-draining tonsil tennis with one victim and posing for a real-life Polaroid with another. Say cheese, bitch! The Dream Master even begins referencing other movies, most notably Jaws, Freddy’s claw taking the guise of the legendary shark’s fin in pursuit of a sunbathing Kristen. He even sports a pair of Wayfarers as he gloats with sadistic opulence, the transition to mystique-crushing caricature almost complete.

Incredibly, the movie was almost a whole lot sillier until New Line stepped in and made significant cuts to a version that was described as, “Too camp and silly.” Harlin, who was so intent on landing the film that he hung around the New Line offices until producer Robert Shaye took pity and hired him, based the nightmare sequences on dreams he’d experienced throughout his life, and at times the movie is a runaway train of imagination, beguiling and absurd in equal measures. Other times it’s just silliness for the sake of it. While writing the film, Harlin would run into James Cameron, who facetiously enquired about how they intended to bring Freddy back to life this time around. Matching the filmmaker’s glibness, Harlin replied, quite randomly, “a dog pisses fire on him,” and low and behold, that very idea made it into the movie. Harlin would even name the dog Jason in a transparent nod to Paramount’s waning marquee killer.

In visual terms, the infamous dog urination scene is rather impressive. Freddy’s total regeneration, from broken bones to fully fleshed-out fritter, is one of numerous visual triumphs from the mind of special effects giant Screaming Mad George, the brains behind Brian Yunza’s satirical body horror Society. He does a hugely impressive job that’s more than befitting of the material, but for me the practical effects featured in The Dream Warriors are infinitely superior, mainly because the mood is so much darker, creating a dichotomy that prevents the movie’s villain from becoming overbearing in comedic terms. Ironically, Harlin initially wanted special makeup effects artist John Carl Buechler to head the project, an Empire Pictures alumni who would land the director’s seat for Freddy vs Jason substitute The New Blood, a movie so censored the special effects team may as well have stayed at home. Buechler was actually behind the film’s infamous dead souls pizza, which for me is the standout visual attraction in The Dream Master, but other than that the film’s surreal flourishes are pure Screaming Mad George, for better and for worse.

The Dream Master‘s unbridled opulence was the death knell for the film’s young cast on the mainstream stage, most of them relegated to bit-part TV outings or simply disappearing altogether, but one actor who remained unscathed by the movie’s calculated hi-jinks was the man responsible for delivering them: the inimitable Robert Englund. Whether you like your Freddy evil or more on the silly side, it’s hard to criticise his portrayer’s unyielding enthusiasm for the role. Englund is typically enigmatic as the movie’s marquee attraction, making the most out of material that may have killed a lesser actor. I’ve never been a fan of Krueger’s slapstick incarnation, at least in my adulthood, but Englund embraces the role like never before, even citing The Dream Master as his absolute favourite instalment. For the first time in the series he looks less like a horror demon, more a fancy dress villain high on valerian tea, and boy does he ham it up! He thrives on the self-referential silliness, stalking his prey like a cartoon crook with a swag bag slung over his shoulder. You can see he’s having a total blast in his new role as antihero. Freddy isn’t your typical horror villain, and that’s down to the man beneath the latex. To say that Englund is one of a kind in the annals of horrordom is a gross understatement.

Rest in hell.

Alice Johnson

As far as I can gather, future Die Hard 2 and Deep Blue Sea director, Harlin, is much more comfortable in the realms of action cinema, something made apparent by a gloriously overblown production that often throws explosions into the mix for the sheer hell of it. In terms of horror, this is tired, frivolous fare, but you can’t deny the fascination of seeing Robert Englund in drag. Nor can you deprive yourself of the opportunity of watching his crater-faced alter ego picking at a past victim pizza, one that will strike fear in the hearts of practising vegans the world over — though likely no one else. Most dizzying is an absurd Freddy rap buried somewhere in the end credits, a slick production with a troupe of soul sisters backing the character’s every brazen boast, and with rhymes like, “With a hat like a vagabond; standing like a flasher; Mr Big Time; Fred Krueger, dream crasher,” the rap industry certainly had nothing to fear either.

The Dream Master knows exactly what it is. It is horror for the MTV generation: shallow, brightly coloured and lacking any real depth or logic, so those who came for the visuals will certainly get their money’s worth. Elsewhere, not so much. The Dream Master features the kind of screenplay that makes disposable pawns of its characters, and when a girl of sixteen manages to turn up for school each morning, seemingly unaffected by the brutal and relentless deaths of her friends and family, you find it hard to care very much about anyone. You can’t knock some of the film’s aesthetic indulgences, but when kids begin walking around their homes in store-bought Freddy pyjamas, you know the magic of the original character has been drained beyond all recognition. Perhaps because of this obsession with all things Krueger, The Dream Master became the most successful horror movie of 1988. Some may prefer the character’s more jovial antics, but for fans of Krueger’s darker incarnation, this is the one where the rot truly set in.

When it comes to characters who inspire horror, overexposure is a killer, and on that level The Dream Master buries Krueger. We see so much of Freddy that he quickly becomes impotent, reborn as New Line’s class clown for millions of watching schoolkids. The only time the film is even remotely scary is when Bernstein’s iconic score creeps in. Beyond that there’s no tension to behold, no attempt to even forge any. Harlin doesn’t try to build any kind of suspense or drama. It’s all spectacle, and as gorgeous as the set decoration is, it all feels just a little flimsy. Much of the film takes place in the dream world, but unlike previous instalments it never really feels like a dream. Even a nifty scene at the world-famous Rialto Theatre, one that sees Alice sucked in through the screen, is fundamentally lacking in the authenticity department. It’s all very Wizard of Oz, though infinitely less terrifying. There are no cute tricks or blurred boundaries to forge that sensory void between dreams and reality. Beyond the eye-watering visuals there’s no real craft to speak of. It’s pantomime, not theatre.

The Dream Master is less a bad movie, more a calculated attempt at tapping into the teen (and tween) demographics. It’s silly because of some unfortunate production obstacles, but also because that’s what the mainstream wanted, and in that regard it’s nothing short of a triumph. But take off the neon-tinted spectacles, cast aside the childhood memories and The Dream Master can be a tough watch at times. It’s all so hopelessly shallow, drugged to the eyeballs on corporate ambition as a then indie New Line looked to capitalise on their once in a lifetime creation. They succeeded too, going on to produce the $2.9 billion dollar Lord of the Rings trilogy before ultimately merging with media giants Warner Brothers in 2008, something that wouldn’t have been possible without the success of the A Nightmare on Elm Street series. New Line Cinema was once dubbed “the house that Freddy built”. If the original movie laid the foundations, The Dream Master turned it into an oversized mansion of spectacularly grandiose proportions.

Director: Renny Harlin

Screenplay: Brian Helgeland,

Ken &

Jim Wheats

Music: Craig Safan

Cinematography: Steven Fierberg

Editing: Michael N. Knue,

Jack Tucker &

Chuck Weiss