Dissecting Brian Yunza’s delirious commentary on Reaganite elitism

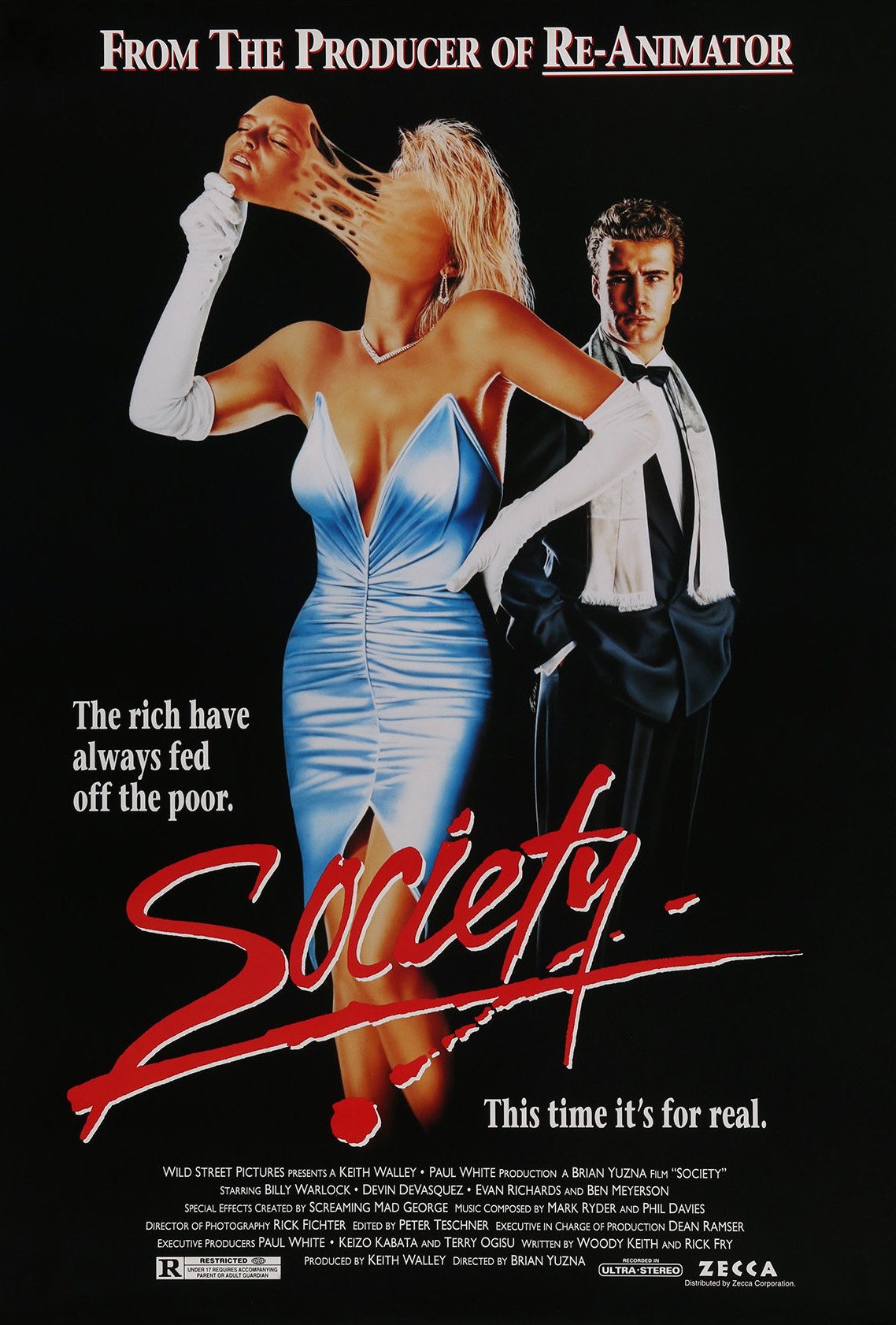

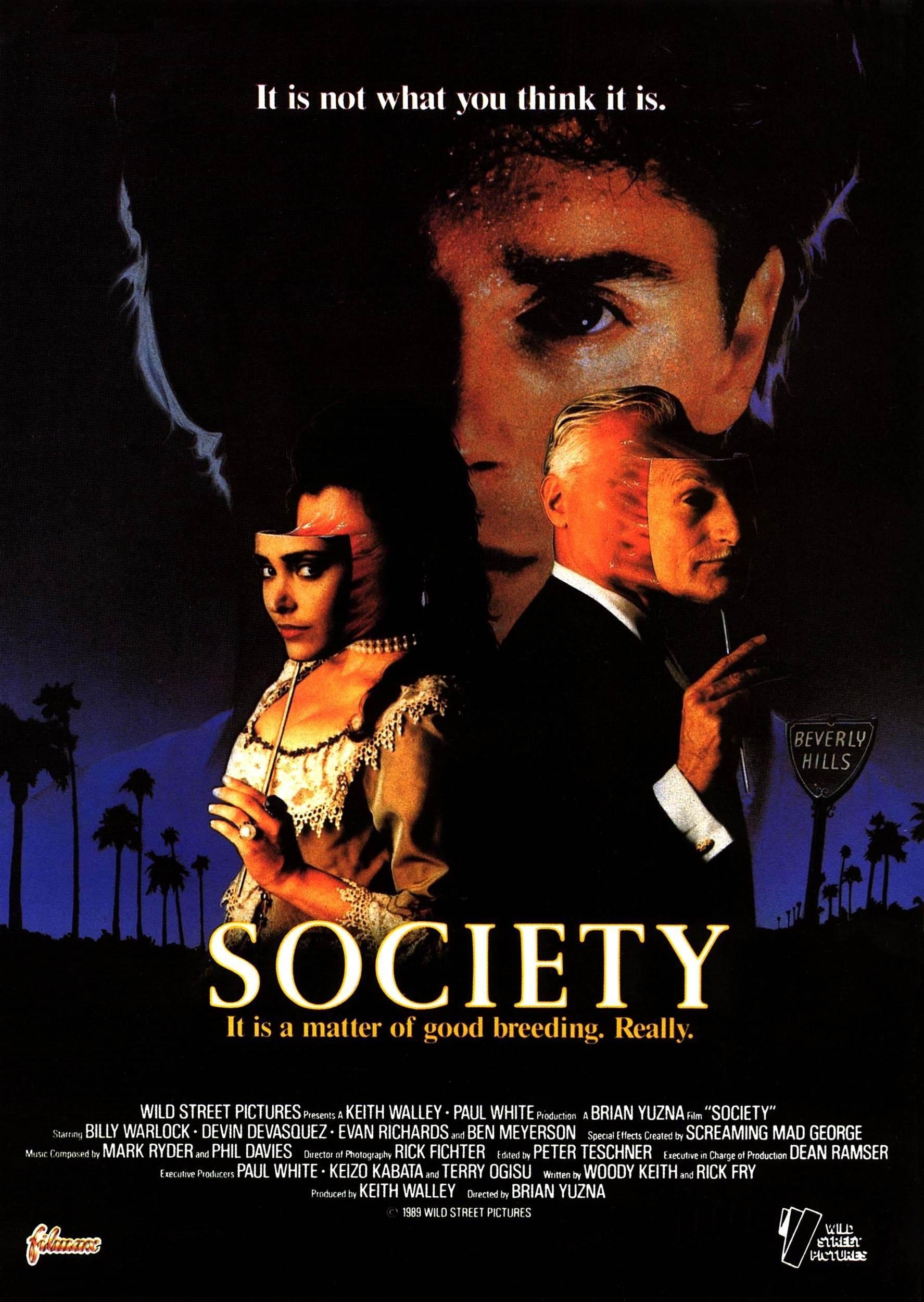

In 1989, Brian Yuzna, the producer responsible for shepherding Stuart Gordon’s seminal Lovecraftian body horrors Re-Animator (1985) and From Beyond (1987) to the screen, set to work on his directorial debut, the wildly OTT social satire and cult body horror classic Society. Taking on a spec script in the shape of Woody Keith and Rick Fry’s Society after a science-fiction project with genre legend Dan O’Bannon, titled The Man failed to manifest, Yuzna set to work. The finished product would ultimately comprise a sordid mash of genre leitmotifs and lasciviousness that would draw influence from a wide range of horror mediums to execute its tale of societal corruption.

Bill Whitney (Billy Warlock) is a paranoid teen living in the super-rich, over privileged, Caucasian environs of an ultra good-looking, status-obsessed Beverly Hills enclave. He’s incredibly handsome, buff, tanned, sporty and popular. In spite of all this he is struggling to fit in. Dissaociative, paranoid, alienated to the point of questioning his own parentage, Whitney is adrift in a kind of pre-adult limbo, sexually uncertain, hormonal and angst-ridden. His family are weird, his psychiatrist is weirder, and then there’s former Playboy pin-up Devin DeVasquez as sexual predator Clarissa, exotic to the point of being alien, who we first encounter uncrossing her legs for Whitney’s viewing pleasure in a scene not dissimilar to Sharon Stone’s police interview in Basic Instinct.

Whitney, having failed to break into society’s preppy, shoulder-padded youth contingent at the behest of cheerleader clone and casual girlfriend Shauna (Heidi Kozak), remains directionless. This continues right up until he is provided with evidence of his family’s extracurricular gratuitousness, via his sister’s ex-boyfriend-turned-stalker, Blanchard (Tim Bartell), who provides Whitney with a tape recording that seemingly confirms his worst fears: that his family are incestuous and involved in a sex cult.

For the most part, Society is an uncouthly executed, broadly satirical Rosemary’s Baby knock-off that attempts to fuse its Ira Levin inspired social paranoia and ambiguity with the mucilaginous, sexually deviant body horrors of David Cronenberg. Although it does not, for the most part, reach the lofty heights of peak Polanski/Cronenberg, it does manage to rise above the B-movie quagmire of standardised 80s horror fodder by addressing a series of similarly contemporary themes in an unconventional and disturbing manner.

Uhm… nothing. I mean, I don’t think about them, they don’t think about me. We’re just one big happy family… except for a little incest and psychosis.

Bill Whitney

The film starts life as a teen melodrama, though it quickly morphs into a cheesy, paranoid, psychosocial thriller as previously discussed. Then, in it’s final act, it veers wildly off course, and rather than giving us the sacrificial cult ending the writers originally envisaged for the script, which would have been more in keeping with Ira Levin and Dennis Wheatley adaptations for Hammer Horror, the film goes full Yuzna, opting for a more subversive conclusion composed of an elasticated morass of fused body parts that causes the jaw to slacken and the brain to shriek in nauseated bewilderment. It’s this sudden, unexpectedly messy deviation from mainstream 20th century horror tropes that elevates the film. Society revels in its clumsily rendered, though nonetheless effective, ruminations on the excesses of elitist societies in which the vulgarities of privilege, capitalism, perfectionism, and the resulting ambivalence they engender are lampooned to disgusting and comical effect.

Sexuality in all its many splendoured forms has always been a key theme in horror, from the impotence of the male vampire incapable of traditional intercourse in most early incarnations of the sub-genre, to the more conservative ‘final girl’ obsessions of exploitative slasher trash, to the body horror oeuvre of David Cronenberg in which dysfunctional, mutating sexual appetites, intrusive technologies and violent tendencies commingle and intertwine to alarming effect.

From the incestuous relationships of parents and siblings and the surreal, hair-munching antics of secondary characters, to the post-coital multi-jointed manoeuvrings of Clarissa and the lolloping synth soundtrack by composers Mark Ryder and Phil Davies, Society is a veritable smorgasbord of absurdity. Then there’s that final scene in which Japanese effects maestro Screaming Mad George’s latex runs amok. The writhing mass of moaning, stretchy, slime-coated meat and flesh on display leaves limited work for the imagination to do. Suffice it to say, there are truly shocking visual images to grapple with that remain with the viewer long after the final credits.

Society’s climactic atrocity exhibition calls to mind Hassan’s Rumpus Room in William Burroughs’ cut-and -paste classic Naked Lunch, any number of JG Ballard books containing sex, transmogrification, violence and technology, the artwork of Francisco Goya, the rubbery fleshiness of David Cronenberg’s seminal cult hit Videodrome, and Rob Bottin’s unforgettably stretchy work on John Carpenter’s The Thing. It also works as a sort of lowbrow forerunner to the erotic dreamscape of Stanley Kubrick’s hallucinatory upper-class orgy in Eyes Wide Shut. Though it lacks the artistic detachment of the Kubrick film or the technical mastery of its seamless execution it works marvelously as a grotesque metaphor for the consumerist depravities of a feral elite. To quote Debbie Harry’s Nicki Brand in Videodrome, ‘I think we live in over-stimulated times. We crave stimulation for its own sake. We gorge ourselves on it. We always want more, whether it’s tactile, emotional or sexual.’

You know the schedule; first, we dine. Then, I fucked your sister. Then, everybody else got so turned on, they fucked her too.

Ferguson

In terms of the drama on offer, it’s safe to say there isn’t a single actor in the film who gives anything near to a decent performance, though whether this is because they’re in on the joke is difficult to fathom. Billy Warlock would go on to a career in Baywatch, where his flawless tan and sculpted hair would compliment the tone of the show perfectly. Devin DeVasquez, meanwhile, hit her commercial peak in Society, before fading from the industry via a surfeit of z-list support roles, only to return later in her career as a TV producer on The Bay.

Thankfully, in this particular instance, rather than hampering the film in any way, the unwieldy dialogue and dire acting is advantageous. Character interactions have a contrived sheen about them, which, whether intentionally or not, adds to the surface vibe of the community under scrutiny. The upper echelons of society are characterized by their affectation. Beneath the surface, a rottenness prevails, represented at the film’s commencement by the putrescence of Whitney’s apple.

Ultimately, for a film that deals primarily in blackly-humorous social satire, it ends on a bit of a bum note. Whitney’s stand against the homogenous blob-like horrors of the status quo results in a Pyrrhic victory of limited significance. Society will continue unhindered, following a bump in the road that is easily negotiated. The rich will continue to eat the poor, quite literally, in order to perpetuate themselves and sate their venal appetites.

However, although it concludes somewhat nihilistically, the film’s warning retains pertinence. In an era that has given us David Cameron’s Pig Gate and Donald Trump as possibly the most morally repugnant, ethically bankrupt president in America’s history, looking back, Society’s prescience is unquestionable. As a blackly humorous, libidinous, and distasteful assault on greed and corruption it retains its impact, and is oddly enjoyable as a glutinous, viscera-strewn horror picture.

Director: Brian Yunza Screenplay: Woody Keith &

Rick Fry Music: Mark Ryder &

Phil Davies Cinematography: Rick Fichter Editing: Peter Teshner