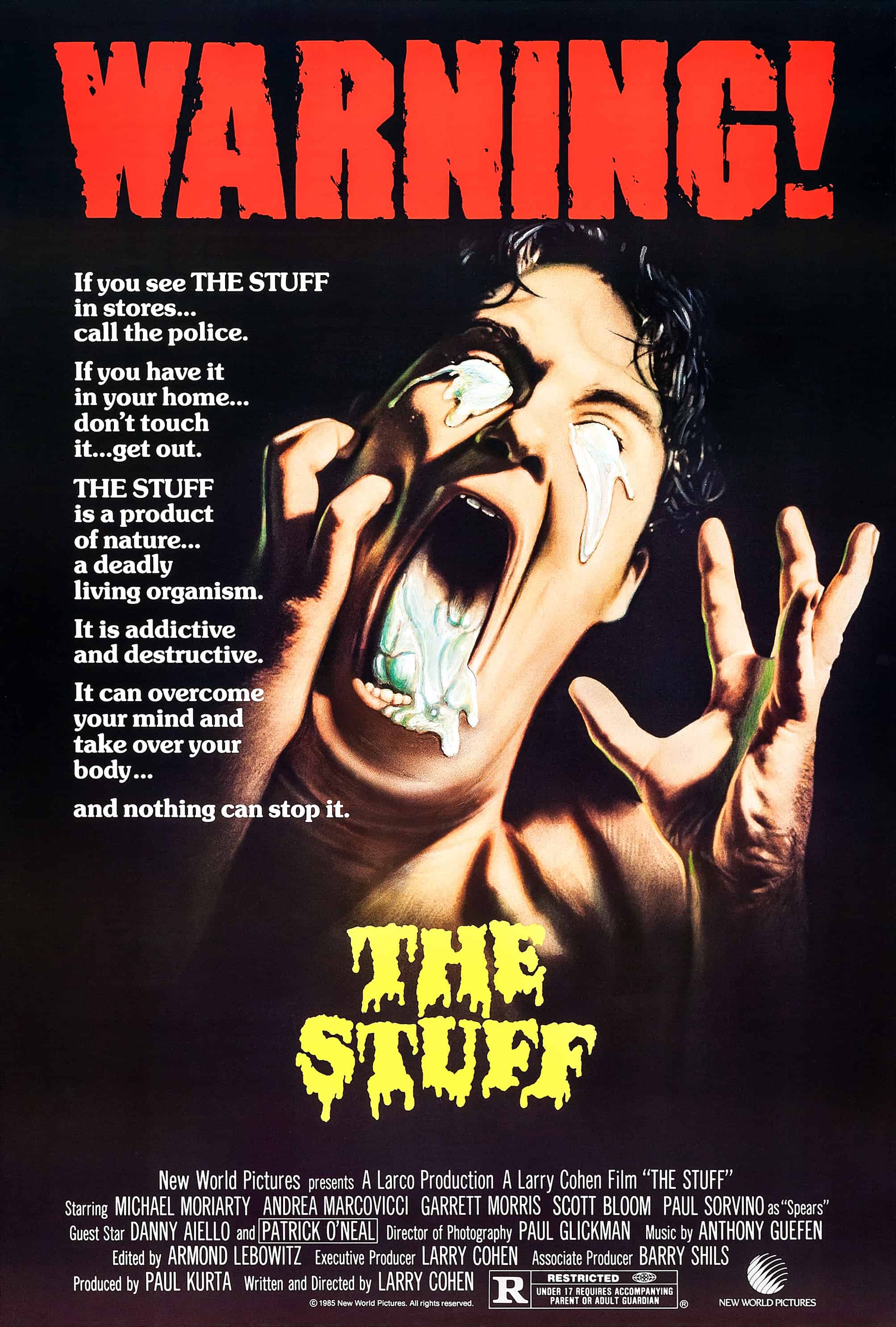

Director: Larry Cohen

15 | 87 mins | Horror

We’re all guilty of lusting after stuff we don’t need, of craving stuff we must have. In a consumer society fuelled by big business, we sometimes depend on that stuff to lend us purpose, to blind us from the often thankless realities of everyday existence. As modern citizens we are slaves to consumer products. We are addicted to fast food, subsisting on a diet of additives and preservatives. We are worshippers of the brand name. You could even say that the stuff we consume, at least in a figurative sense, has begun to consume us. In the wonderfully madcap world of writer/director Larry Cohen, that sentiment becomes something much more literal, and infinitely more fun.

The Stuff isn’t your average horror flick. At its core it’s a cute nod to the Cold War B-movies of yore, the kind that unleash an unidentified, all-consuming threat on everyday suburban America, only this time it’s capitalism, not communism, that comes under attack. Much like George A. Romero’s zombie classic Dawn of the Dead, a movie that sees the braindead denizens of mall life instinctively descend upon their consumer stronghold for a bout of mindless window shopping, the movie lampoons our ingrained willingness as brand loyalists and our inclination to submit to any old craze we’re systematically spoon-fed. As a species we’re attracted to trends, susceptible to peer pressure — something multinational conglomerates and their armies of ad executives are only too eager to exploit.

There were many 50s throwbacks in an era when directors leaned on their nostalgia for the decade, remakes such as John Carpenter’s The Thing and Chuck Russell’s The Blob given high-tech updates with modern sensibilities, but none of them lampooned the Reagan 80s as ruthlessly as The Stuff. The Thing, while retaining the fear and paranoia central to Cold War movies at a time when nuclear armament was considered a serious threat to humanity, was mainly a platform for practical effects advancements, as was The Blob, which presented us with an upgrade on the gelatinous red threat that was more in sync with the nation’s AIDs epidemic than the hysterical notion that a foreign ideology might consume the hearts and minds of American citizens. That kind of thing may have flew in the 1950s, but there’s a reason why those movies were considered kitsch by late-20th century standards.

Of course, Cohen being Cohen, he went the other way, retaining those kitsch qualities in a way that highlighted the absurdity of it all. He would also ditch the thinly-veiled propaganda for social critiques on surreptitious threats that were much closer to home. The avoidable horrors of the Vietnam War had left America’s post-Watergate generation more suspicious of their own leaders than any foreign threat, something that had to be corrected. The Civil Rights Movement and the optimistic idealism of hippie counterculture was a blow to big business, their “no work, no possessions” mantra a threat to the compliant society of happy consumers cooked up on Madison Avenue. That’s where globalization came in, a process that lowered standards and increased our capacity for consumption, introducing threats that not only went undetected, but unreported.

As well as highlighting our weaknesses as modern consumers, The Stuff acts as a commentary on the surreptitious nature of manufacturing and the unseen hazards we’re so willing to overlook. This subject has never been more relevant than it is today. There was a time when dangerous items were produced based on our ignorance as an evolving society — asbestos for example — but today additives and preservatives are everywhere. Thanks to the growing demands of capitalism and mass production, even our most basic and natural foodstuffs are swimming with cancer-causing agents, new-age products such as diet soda, promoted as being part of a healthy lifestyle, containing both aspartame and acelsufame-k. In short, manufacturers are ignorant to the long-term effects of what we are consuming, but as long as their products sell they couldn’t give a damn it seems; and, perhaps more worryingly, nor could we.

There is similar abandon in the business practices of those behind The Stuff, the kind of product that becomes a self-fulfilling institution after quickly wrapping the nation in a candy cotton cloud of sweet-tasting commercialism. After stumbling upon a mysterious white mush erupting from the earth, a petroleum refinery worker thinks nothing of popping it in his mouth and is immediately hooked. Soon enough, this unexplained gook is everywhere — a creamy, delicious dessert which is practically calorie-free and comes pre-packaged in a family-friendly pot, an added bonus for the aerobics-obsessed housewives genuflecting at the alter of Jane Fonda workouts. For the plainclothes suburbanites of modern America, The Stuff is a dream come true.

For peewee protagonist Jason (Scott Bloom), that dream quickly becomes a nightmare as he watches his family succumb to The Stuff’s addictive qualities. As well as gorging on the nation’s latest ubiquitous delight, they’re transformed into a real-life food commercial, aggressively pursuing his allegiance and becoming physical when he fails to cooperate. The boy is initially conflicted. He’s never had a reason to doubt his parents, but as events grow progressively weird Jason remains unconvinced, particularly when he opens the fridge to see the product moving of its own accord, freaking out in a supermarket of wall-to-wall Stuff and fleeing his home as the wholesome nuclear family gets set for meltdown.

Jason isn’t the only one suspicious of the mysterious gunk sweeping the nation. Corporate bigwigs, who naturally view the product as an ingenious creation that is lethal only to their wallets, are beginning to feel the financial burn as consumers shun junk food of the less sentient variety for The Stuff’s sweetly addicting taste, and when they fail to reach those bribeable folk at the Food and Drug Administration, they turn to industrial spy Mo Rutherford (Michael Moriarty), a cynical southern dandy who’ll stoop to pretty much anything if the money is right. While investigating, Moe runs into ousted cookie king Chocolate Chip Charlie, a blatant parody of Wally Amos of the popular Famous Amos cookie brand.

Charlie is played by comedian and former Saturday Night Live regular Garrett Morris, who described the movie’s production as “crazy”, not taking too kindly to Cohen’s notoriously maverick ways. In fact, Morris, who battled a cocaine habit for close to thirty years, has since admitted to regretting his entire B-movie run, films such as The Stuff, Children of the Night and Santa With Muscles helping to fund a habit that only worsened after the actor was robbed in broad daylight and seriously injured. Morris was shot in the intestines on February 24, 1994 and remained in a wheelchair for the best part of a year, an arduous period of rehabilitation putting his acting career firmly on hold. On working with Cohen, Morris, who would rediscover success on TV shows such as Martin and 2 Broke Girls, would joke, “Oh my god, I hope you never see [The Stuff]. That was my horrible period… I don’t get into all of that.”

According to renegade filmmaker Cohen, the original cut of The Stuff was far more “dense and sophisticated,” before being sacrificed for the sake of pacing, and you can almost taste the acid satire of those lost entrails. As highlighted in a quote taken from Larry Cohen: The Stuff of Gods and Monsters, The Stuff was something of a personal crusade against the unseen hazards of an increasingly global market. “My main inspiration was the consumerism and corporate greed found in our country and the damaging products that were being sold,” Cohen would recall. “I was constantly reading in the newspapers about various goods and materials being recalled because they were harming people. For example, you had foods being pulled off the market because they were hazardous to people’s health.”

The most obvious comparison to be made is of course McDonald’s, who have undergone something of a 21st century makeover, focusing on calorie counts and providing healthy alternatives to the triple-fried nuggets and heavily-sugared soft drinks that have transformed the fast food chain into a worldwide brand of oppressive proportions. Instead of Chocolate Chip Charlie, we have the universally recognised Ronald McDonald and the ironically named Happy Meals to entice children into a lifetime of nutritional enslavement. After all, is there really much difference between a tub of The Stuff and a large, creamy helping of McFlurry? Remember to check your fridge at night to see if it’s moving.

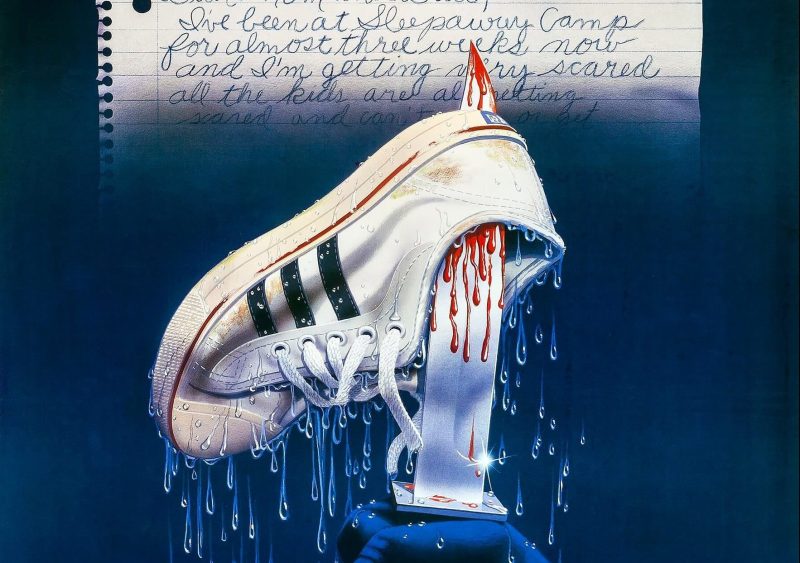

A step up from the Nike products we willingly pay top dollar for in order to become walking billboards, The Stuff takes brand loyalty to a whole new level, the kind that would make McDonald’s chiefs green with envy (let’s just hope they’re not taking notes). Not only does society’s sweet new sensation create unconscious advertisers and purveyors, it turns addicts into ruthless guardsmen who sacrifice their lives for the continued prosperity of the product. There’s no longer a need to convince naïve rubes with multi-million dollar ad campaigns. Thanks to The Stuff, commercial hysteria has taken on a life of its own. No wonder those bigwigs were so hellbent on stealing the formula!

When entire families begin disappearing, Rutherford’s investigations lead him to a production site in Georgia where The Stuff has developed into something rather more insidious. Subjected to a savage attack by a furtive batch hiding in his pillow, Rutherford realises that the product is more than just a benign organism. It’s a parasitic entity that inhabits the body and mind before leaving its human carriage dead and empty (insert latest consumer fad here). Recruiting the help of resplendent ad exec Nicole and the commie-bashing Colonel Spears (Paul Sorvino), Moe takes to the airwaves in an attempt to recapture the minds of America, but even if successful, this is surely a case of winning the battle and not the war.

The Stuff bombed at the US box office, partly because it received only a limited theatrical release from New World Pictures, who were unhappy with the fact that Cohen had produced a Cohen movie and not the kind of blood-and-guts horror that was dominating the video market (they obviously had no idea who they were dealing with). Critically, the film fared much better, though thanks to a rather unfortunate turn of events, potential audiences were none-the-wiser. As Cohen would explain, “The day The Stuff opened in New York a hurricane hit and the newspapers were not delivered. Of course, we had received all these great reviews, but it didn’t matter because nobody ever got to read a single word of them.”

Perhaps there were other forces at work.

Cookies and Cream

The Stuff may not live up to the madman-in-the-hockey mask trends of early-80s horror, but there are some truly icky practical effects on display in a movie that cost little more than a million bucks, the most grotesque coming in the form of the newly-recruited Chocolate Chip Charlie’s physical meltdown.

After agreeing to lend his voice to the Stuff-denouncing airwaves, the supermarket celebrity suddenly regurgitates a huge load of the sinister goop, which uses him to infiltrate the base of the resistance before reducing his head to a quivering pile of chunks. Yuck!

Food for Thought

Food usually falls into two categories: mass-produced, store-bought garbage and pricey, organic produce enjoyed by the few, but sentient food that can plot and execute world domination has never been on the menu. Until now.

Having had his sleep interrupted by a batch of vengeful goo, Rutherford is left helpless as it clings to his face and attempts to suffocate him. Luckily, girlfriend Nicole is at hand with a jar of oil and some matches.

Okay, honey, try to stay calm. This might burn a little.

Choice Dialogue

Forced to eat shaving cream as a way to convince his wild-eyed family of his allegiance to The Stuff, Jason has a little accident in the back of Rutherford’s car.

Jason: Excuse me, sir. I kinda just threw up in your car.

Rutherford: I know!

Jason: I’m sorry. I mean, I just ate shaving cream.

Rutherford: It’s alright. Everybody eats shaving cream once in a while.

Beneath the eye-catching special effects and commie-bashing, B-movie nods,

Edison Smithis a razor-sharp satire on the perils of consumerism — the kind that has never been so relevant — and by the end of the movie I wasn’t so much concerned with exploding heads or polluted torsos. I was instead troubled by a solitary question: if capitalist strongholds such as Walmart could get away with selling The Stuff, would they? The answer is yes, they probably would.