VHS Revival enters the darkly sensuous realm of one of horror’s bleakest creations

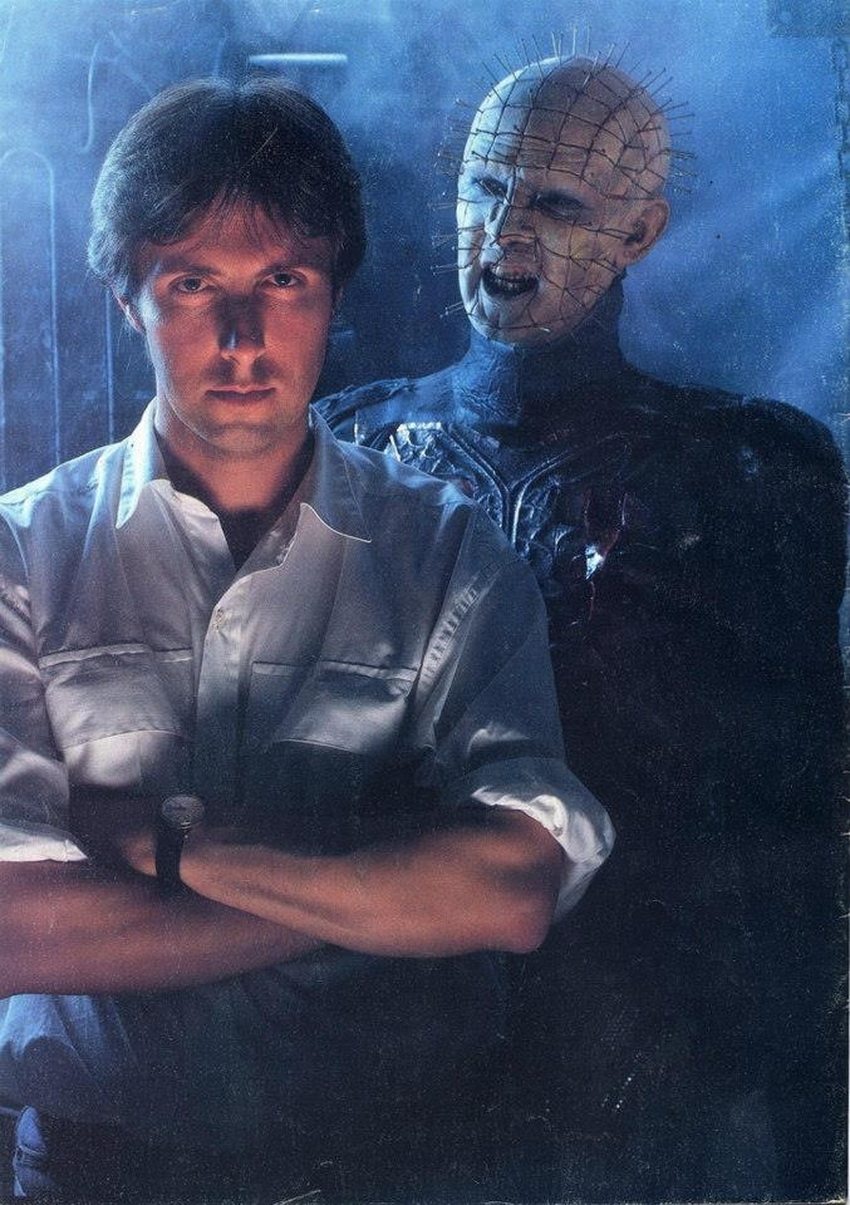

One of the most striking elements of Hellraiser is that the cenobites, a brethren of malformed demons who introduced audiences to a new dimension of terror back in 1987, are essentially secondary characters — at least that was the intention when producer Christopher Figg and New World Pictures backed cult author Clive Barker’s refreshingly dark directorial debut. When it comes to modern horror’s most notable figures, Pinhead is one of the most iconic, but he wasn’t planned as a franchise player in the Michael Myers mode. In fact, Pinhead wasn’t even intended as the lead cenobite, the character a mere passenger who’d grow in prominence due to make-up difficulties that prevented other cast members from delivering their lines.

Initially, it was lip-licking monstrosity, Butterball, and the receding-gums eyesore known simply as Chatterer who took centre stage, the two bequeathing their dialogue duties to Bradley’s black-eyed demon and Grace Kirby’s wire-headed monster, Open/Deep Throat, whose aura of femininity makes her arguably the most perverse creation of all. A series of steadily diminishing sequels would expand on the cenobite legacy, Pinhead becoming more central to proceedings as the series unfolded, but the original instalment kept the cenobites largely in the shadows. In terms of screen time, they were very much outsiders looking in.

Commercially, it was a very different story. If the 80s taught us anything, it was that a memorable horror villain is key to franchise immortality, and it was Pinhead who ultimately found his way onto the film’s press material with his deathly blue cranium of nails, a startling image that leapt out of the video isles like a real-life monster in a realm of fanciful fiction. For many low-budget distributors, canvas art was a form of promotional chicanery that disguised a film’s deficiencies. In an oversaturated home video market it was important to simply stand out. It wasn’t like today when all you have to do is search Google for a mountain of reviews and opinions on any given movie. There were no fully loaded streaming devices to turn to if your choice proved a bad one. Most of the time you relied on impulse, and great cover art, however inferior the film, played a huge part in that.

With a meagre budget of around $1,000,000, you could have forgiven Barker and New World Pictures for taking a similar approach, but Pinhead needed no disguising. In fact, it would have been silly to not use his image as the film’s main selling point. So startling was Pinhead’s look back in 1987 that portrayer Doug Bradley went unrecognised when out of make-up at an after-shoot party, the actor regarded as a stranger by cast and crew members he’d previously spent hours working with. He wasn’t offended. The make-up process was such an image-altering hardship that each application took a gruelling 6 hours to complete, and Bradley was hardly a familiar name back then, the fledgling actor almost cast in the small role of removal man, one he initially opted for over that of the film’s most notable creation as he didn’t want to have his face hidden. Talk about monumental decisions.

All these years later, it’s hard to imagine Pinhead as anything but the leader of the cenobites. What made him most interesting was that, despite his visual extravagances, he wasn’t your typical masked killer. There was something distinctly human about his appearance, which made his disfigurements all the more unsettling. When I rented the movie as a kid, I figured it was just another in a long line of throwaway slashers, though for once I wasn’t disappointed when I discovered it was something else entirely. I didn’t fully understand what I was witnessing, but it was all so morbidly fascinating, particularly the film’s icky visuals, which were a far cry from Fred Krueger’s eye-catching, yet distinctly comedic practical effects set-pieces. Who were these creatures and why would they self-mutilate in such a manner? It was a concept that was completely alien to me. I would later discover that Cenobite is a word meaning, ‘a member of a communal religious order’, their aesthetic inspired as much by Catholicism as it was punk fashion and underground S&M culture, a sacrilegious hybrid that would likely have sparked moral outrage if not for the movie’s lack of obvious iconography.

Explorers… in the further regions of experience. Demons to some, angels to others.

Pinhead

Six years earlier, supernatural tech horror Evilspeak was banned outright for an overtly blasphemous finale that saw a priest impaled with a nail from a crucifix, and that film wasn’t half as graphic as Hellraiser. By 1987, the Video Nasty scandal, a tabloid-driven indictment of modern horror that saw 72 titles banned in the UK in accordance with the Video Recordings Act of 1984, had served its political purpose, but horror had adopted a self-aware approach that relied on humour and gimmickry to appease the censors and swerve the costly re-editing process imposed on content deemed too violent or sexual. In the US, poster boy for moral outrage Jason Voorhees had been transformed from a dead-eyed killer into a meta cultural icon. Horrifically scarred child killer Fred Krueger was on the verge of becoming an unlikely role model to kids the world over with his money-spinning brand of eye-catching SFX, cute one-liners and questionable merchandising power. Sam Raimi was even forced to remake banned horror classic The Evil Dead, 1987’s Evil Dead 2: Dead by Dawn an almost straight-up re-tread with a bigger emphasis on humour.

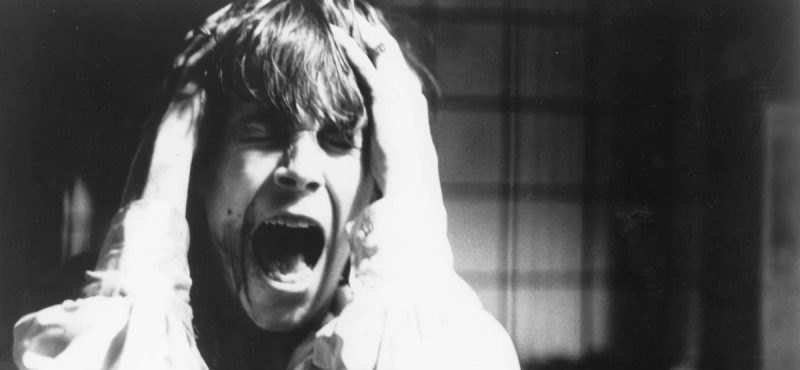

At a time when violent horror with genuine scares was on the verge of extinction, Hellraiser was a completely different entity, a relentless exercise in dread that was unique, intelligent and deeply disturbing. Significant cuts were still required after the MPAA burdened the film with the dreaded X rating, most notably a trimming-down of Frank’s deliriously graphic ‘tearing apart’ at the hands of our vengeful demons, an insidious rabble who approach their work with an amoral pragmatism that defies notions of good and evil, allowing Hellraiser a richness typically lacking in the realms of graphic horror, but it was a far cry from the puerile antics of some of the genre’s most prominent names. The film’s erotic scenes also came under fire, which was more problematic from a narrative perspective because many of the movie’s characters are driven by lust, sexuality, and sadomasochistic acts that, at least for some, make pleasure and pain indivisible.

A dark literary phenomenon like Barker was no doubt troubled by such impositions, but in reality he was relieved to finally have a sense of control after clashing with producers on two other adapted works in 1985‘s Underworld and 1986’s Rawhead Rex, experiences that inspired him to pick up the camera himself. Hellraiser is based on Barker’s novella, The Hellbound Heart, which was actually written with an adaptation in mind and published in November 1986, less than a year before the release of its cinematic incarnation. Previously, Barker’s work had been disfigured beyond recognition, particularly in George Pavlou’s aforementioned ‘Rex’, which would eschew much of what made Barker’s creation so unique, ditching themes of paganism and Christianity for a straight-up monster movie and transforming the eponymous Rex from a creature of substance into a dumb beast with basic stalk-and-slash tendencies. With Hellraiser, Barker was finally able to deliver a loyal adaptation that captures the essence of his unique literary exploits, giving us monsters with purpose, and it’s an experience to behold.

Fellow author and genre wizard Stephen King once proclaimed, ‘I have seen the future of horror and his name is Clive Barker’, and Hellraiser is a debut of startling accomplishment. It’s not particularly innovative from a technical standpoint, but its colourless nihilism and almost ceaseless sense of dread saturates you to the bone. Some might point to the cheapo special effects featured towards the end of the movie — animation that was hand-drawn by Barker in a single weekend after the budgetary rivers had run dry — but overall there’s nothing kitsch or ridiculous about Hellraiser, a movie that wades neck-deep through swamps of viscera and never strays too far from darkness.

Barker’s vision is relentlessly bleak and remarkably violent, exploring humanity’s taboo desires in a way that exposes our own capacity for evil, all of this heightened by the cenobites and the queer aura of sensuality they exude. The way Barker unleashes them upon the movie’s suburban house of horrors, all self-assured omnipotence and creeping lights, leaves you feeling like there’s no escape, a sense of futility punctuated by Christopher Young’s colossal score of impending doom. Young’s musical accompaniments are an absolutely vital component of Hellraiser‘s power of seduction. They add such a richness and sense of otherworldly magic. There’s a reason why Barker’s film seems much bigger and bolder than its budget would suggest.

Interestingly, our rabble of sadomasochistic minions are not the movie’s main source of malice. That title belongs to Frank the Monster (Oliver Smith), whose vindictive spirit and incessant self-regard puts our cast of malformed monsters to shame. The cenobites are not strictly evil. Sure, they belong to the realms of hell, a place to which they cannot return without a victim to subject to the kind of torture that makes them angels to some and demons to others, but their deeds have boundaries; in some ways, their wickedness is relative and tied to necessity. Though it would inevitably become Pinhead’s adopted moniker, ‘Hellraiser’ actually refers to Frank, a self-serving sadist so devoid of empathy he feels immune to the perils of evil — at least the Earthly kind. His callous, grand guignol regeneration at the expense of a plethora of everyday schmoes is positively horrifying, as is the quite astonishing moral transformation of Claire Higgins, who steals the show as Frank’s ethically ambiguous and hopelessly lustlorn lover Julia.

Higgins forges a character who treads a tenuous line between good and evil, much like the cenobites themselves. Julia is bored with her domesticated life and dutiful husband, dreaming of the illicit affair she had with Frank until the day he re-emerges from the recesses of Pinhead’s realm to reignite her sinful desires. Julia begins as a somewhat fragile figure, a person repressed by the memories of the miscreant who once lit a fire under her mundane existence and who’s irrevocably drawn to danger like a moth to a flame. When Frank sends Julia out to lure victims to his attic-bound trap so he can feast on their flesh, she is initially horrified, withering at the very prospect, but once that line has been crossed she’s a very different creature, as prone to frantic hammer attacks as she is to retreat.

It’s clear from the outset that Julia’s suburban life is alien to her. Much like the fictional puzzle box, known in Barker’s stories as The Lament Configuration, that opened the gateway to some elaborate hell, Frank opened Julia up to a wickedness that altered her disposition irredeemably, one that’s tied to her undying attraction to him. By the movie’s final act she’s fully embraced that wickedness, the stimulation of the kill becoming almost sensual as Frank’s total regeneration draws ever nearer. Julia takes the phrase ‘do anything for someone’ to levels rarely glimpsed, though a female crew member had a rather blunt take on her motivations while Barker searched for a title other than The Hellbound Heart that would suit the studio, suggesting What a Woman Will do for a Good Fuck. Quite the mouthful for a marquee title, though I’m sure there were other, more pressing reasons why that particular suggestion was overlooked.

Watching Hellraiser, I was surprised by how little we see of Pinhead and his mutilated brethren. This is a horror movie, and such monsters thrive on mystique, making their screen time all the more memorable, but Frank and Julia are the real stars of the show, delivering the kind of profoundly disturbing performances that encapsulate the director’s despairingly amoral vision. The evolving Frank is a miracle of practical effects. His initial emergence from wimpish brother Larry’s spilt blood is still awe-inspiring, as is the skeletal tower of sinew who clings to the shadows awaiting his next victim — an astonishing achievement considering the budget at hand. After escaping the box-bound torture of the cenobites, his character revels in the process of parasitic regeneration, feeding on his victims as if slurping pulp through a straw. On some level, he seems to enjoy it too. This is a man so motivated by sadistic acts that nailing rats to the wall and needlessly revealing himself to his horrified niece are the kind of small pleasures he relishes in. Frank is a user of the worst variety, a feeder on emotions who delights in the very process, and the movie’s purest source of evil.

[voice-over] I thought I’d gone to the limits. I hadn’t. The Cenobites gave me an experience beyond limits. Pain and pleasure, indivisible.

Frank the Monster

Also strangely on the sidelines is quasi final girl Kirsty (Ashley Laurence). She has all the requirements for the role, but she seems more of a commercial necessity than an essential character. That’s no slight against the actress. Laurence does a fine job as the cenobite decoy toiling with hellbound dominions, though the movie is arguably at its weakest whenever she takes centre stage. If you compare her role to that of Laurie Strode in Halloween or Heather Langenkamp in A Nightmare on Elm Street, Kirsty is less central to proceedings, a character who stumbles onto the movie’s central narrative rather than being at its core. Like the cenobites, she wanders on the periphery of the film’s tragic love triangle, disconnected from the excruciating emotional conflict that makes Hellraiser such a gruelling experience.

There’s a reason for this. In the book, Kirsty isn’t the moral princess of a morally bankrupt tale. In fact, she isn’t even Larry’s daughter. She’s a friend of Larry’s who’s secretly in love with him and attempts to unfurl Julia’s illicit affair partially for her own benefit. She’s still the heroine of the story, the purest of a stifling rabble of miscreants, but she isn’t the teenager in peril that became a prerequisite for horror in the 1980s. The fact that she is still one of the genre’s most fondly-remembered final girls is indicative of the movie’s unconventional allure.

Like most low-budget horror movies looking to make a commercial impact, Hellraiser is not without its flaws. Scenes in which we glimpse the domains of some hellish realm, while setting up 1988’s visually sumptuous and conceptually intriguing sequel Hellbound: Hellraiser II, see events briefly lose focus, audacious sequences involving monster animatronics proving somewhat superfluous. They’re fast-paced and exhilarating enough, offering a little respite from the movie’s almost ceaseless sense of brooding, but Hellraiser works best as an intimate exploration of the power of seduction, proving that we don’t have to look far beyond ourselves to identify the world’s real monsters.

Of Stephen King’s glowing admission, legendary critic and perennial horror detractor Roger Ebert would write, “Now there’s a blurb Stephen King should have written under one of his pen names. He may have seen the future of the horror genre, but he has almost certainly not seen “Hellraiser,” which is as dreary a piece of goods as has masqueraded as horror in many a long, cold night. This is one of those movies you sit through with mounting dread, as the fear grows inside of you that it will indeed turn out to be feature length.” A scathing criticism, but one that works just as well as a compliment; angels to some, demons to others.

As a horror-obsessed youngster who was likely more desensitised than most, there were very few films that affected me so deeply. Halloween, The Evil Dead and Amityville II: The Possession were three that did a fine job of keeping me awake at night, and Clive Barker’s Hellraiser fell into that same category. Halloween just had that aura about it. It didn’t matter if the action was unfolding in the blackness of night or in the drab palettes of the daytime, it had me by the throat. The Evil Dead was a distinctly wicked experience that left me running for the proverbial forests before I’d even reached the second act, and Amityville II was an ugly little movie that left a bad taste in the mouth and a vile bug in the brain.

As for Hellraiser, I was more perplexed than anything. Though its sheer morbidity saturated my senses, it just wasn’t conventional enough for me to fully grasp. Were the cenobites evil? They certainly looked and sounded evil, but when Pinhead banished Kirsty from the attic with the immortal line, “This is not for your eyes!” I had them pegged as the good guys. Only years later did I come to understand that such delineations do not exist in the further reaches of experience.

For me, Pinhead is a character who will always be shrouded in mystique. Unlike Krueger and co., he isn’t motivated by the urge to commit evil deeds. Instead, evil is his duty, a fact that makes the abhorrent acts undertaken on his watch all the more unsettling. It’s one thing to fear an irrational evil, but the kind that is preordained, reasoned and even logical is a much more unsettling prospect. It’s this kind of strange philosophy that sets Hellraiser apart, giving us not a clearly delineated monster but blurred margins, exploring the idea that pleasure and pain are determined only by the beholder, while notions of good and evil are often subjective.

Director: Clive Barker

Screenplay: Clive Barker

Music: Christopher Young

Cinematography: Robin Vidgeon

Editing: Richard Marden

Tony Randel

Fantastic write-up! Clive Barker is my all-time favourite writer, and he did create something special with Hellraiser. The cenobites design was a feat. He was a true artist, with such fascinating ideas on pain and pleasure too. I’ve always thought it a shame that he stopped directing films, but am thankful we still get to read his phenomenal novels.

LikeLike

Hi Jade. Thanks for the kind words! Barker is such a unique personality who never fails to impress me conceptually. Maybe he’ll return to directing one day, though the industry has moved on since 1987 in so many ways. Plus, he’s 67. 67!! Hard to believe.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The original Hellraiser is a fantastic, frightening and visceral horror movie. The mystery around Pinhead and the cenobites is compelling, the main story is thrilling, and the special effects are excellent. A great horror film, always enjoy watching it.

LikeLike

I agree. There’s nothing quite like Hellraiser. Absolutely stifling dread throughout and a queerly engrossing experience. Oliver Smith is pure evil as ‘Frank the Monster’ and Claire Higgins is just superb as the lovelorn and deeply troubled Julia.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Its the dark, warped characters like Frank and Julia that make Hellraiser such a riveting film. The Cenobites are scary and mysterious, I like how the mystery builds, and the gory finale is stunning. I still think Franks resurrection and eventual demise via Pinheads chains are some of the best practical effects I’ve seen in a horror film.

LikeLike

Hi, Paul. Agreed on all accounts. I think the movie works better as an intimate portrayal of seduction. For me, Frank is the movie’s true evil and Julia’s transformation is terrifying. As for Frank’s regeneration, I’m amazed they were able to pull it off on such a tight budget. Easily one of my favourite practical effects sequences. Absolutely stunning.

LikeLiked by 1 person