VHS Revival takes to the backwoods with Sam Raimi’s quintessential Video Nasty

When you hear the term ‘video nasty’, what’s the first thing that leaps to mind? Many words and images flash before my eyes: lurid depictions of death, cannibals, slashers, snuff, exploitation, sleazy marketing, moral panic, political skulduggery — it’s a mishmash of amorality. In terms of titles, upon which many sub-par productions were sold, some movies that leap to mind are Driller Killer, Faces of Death and I Spit on Your Grave. Those were the films that were whispered in the playground, that introduced me to the magic of fabled dread as a horror-obsessed preteen.

Driller Killer wooed me with its title alone. I knew very little about the actual plot but its savvy, Hooper-esque marketing had me from the get-go. The events in I Spit on Your Grave were explained to me in explicit detail by an older girl who took great pleasure in polluting my imagination with tales of brutal castration. Faces of Death was perhaps the most intriguing of all, about on par with the infamous missing shard-through-the-eyeball moment in Lucio Fulci’s dreamily nihilistic Zombie Flesh Eaters. Were there really movies in which people died… like, for real? The answer was yes and no. I mean, technically they did, but not in the way I’d been told by kids claiming to have seen it back in the late 1980s.

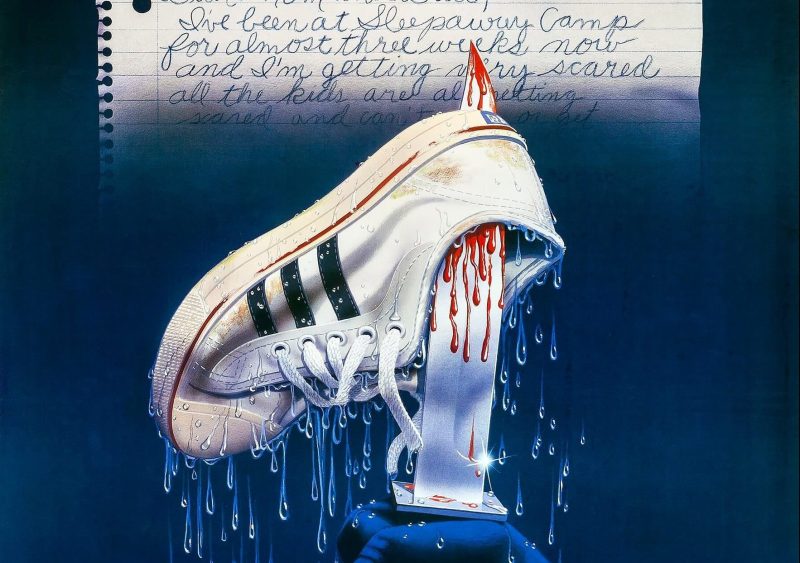

In the end, my first ‘video nasty’ was none of the above. It was a movie I’d heard things about, one whose cover I’d stared at obsessively in the horror section of the local video store at the turn of the 90s following a much-anticipated re-release. The image itself was enough to give you nightmares — not the US version included at the beginning of this article, but the much grungier UK version designed by a young British artist by the name of Graham Humphreys that scared the living shit out of me. Humphreys was twenty years old when asked to work on the design for The Evil Dead‘s UK quad — his first entry into the world of film.

Speaking of his experience, Humphreys would explain, “Steve Woolley gave me a call and asked me to come in and look at a film, which was screening then at the Scarlett Cinema at King’s Cross… it was a new print and hadn’t been cut at that point and there was one other person watching the film with me in the cinema, and they left after about a quarter of an hour. I think to be sick, probably… the whole feel of the poster and the campaign was very sort of punk anyway… it was very grungy-looking as well, and it just got away from the whole American gloss.”

There is something distinctly wicked about The Evil Dead that most ‘video nasties’, and indeed horror movies in general, fail to achieve. This is largely due to the film’s then rookie director, Sam Raimi, who put the majority of low-budget filmmakers to shame with a splash panel siege of breakneck terror that audiences just weren’t prepared for. It was clear from the beginning that Raimi wasn’t just another hack looking to cash-in on the burgeoning home video market. This was a prodigious talent who failed to yield to his financial limitations and in doing so created something quite formidable.

Author Stephen King, the undisputed king of horror back in the 1980s, famously saw The Evil Dead at Cannes and called it ‘the most ferociously original horror film of the year’. Respected critics Siskel and Ebert, who were notoriously opposed to graphic horror for the most part, admitted to disliking the movie, though Ebert was much less close-minded, admitting, “I didn’t enjoy it, either, but I think I would have to give credit to the craftsmanship of the film. It was obviously inspired by Night of the Living Dead and it’s a very pure film, and apart from all these other dead teenager knifing, slashing movies we’ve had over the past several years, this one distils everything right down to the very basic things.”

[possessed] Soon all of you will be like me… And then who will lock you up in a cellar [cackles]

Cheryl

Ultimately, that’s what makes Raimi’s small-scale masterpiece so superior. It doesn’t waste time with characterisation or dialogue. It is 85 minutes of relentless horror that never stops for breath, assaulting you with vile images and nerve-shredding sound design that is so relentless it pushes you to the edge of insanity: the creaking sounds of a semi-dilapidated cabin, the oppressive hum of a lurking presence, the twisted groans of a forest alive with evil, and that’s before we’ve even witnessed anything. Later, it’s the searing splatter of gore, the cackling insanity of the awakened dead, those moments of pure nastiness that crawl under your skin and set in like rigor mortis, exploding in a torrent of sheer bedlam. The movie pushes its characters, and its audience, to the absolute brink and then some. By the end it feels like you’ve been dragged through hell backwards.

King was absolutely blown away by the movie’s presentation, his approval bringing The Evil Dead immediately to the public’s attention. Unfortunately, it was less well-received elsewhere, particularly by those with the power to banish it to commercial purgatory indefinitely. In 1984, the British government, led by ‘Iron Lady’ Margaret Thatcher, responded to a tabloid smear campaign and the efforts of activist Mary Whitehouse to criminalise filmmakers involved with the then unregulated, pre-certificate VHS market. A puritanical individual who openly opposed social liberalism and the autonomy of the individual, Whitehouse set out on a personal crusade to quash civil liberties that played right into the hands of Conservative party politics. The cessation of the coal mines had resulted in mass unemployment in the UK, leading to abject poverty and even the loss of homes as a generation prepared for a life on welfare.

Mass protests followed, most famously the 1984 Battle of Orgreave, which saw miners and the local constabulary clash in a bloody battle that for years was blamed on the miners in a vile instance of propaganda that was described by BBC journalist Alastair Stewart as “a defining and ghastly moment” that “changed, forever, the conduct of industrial relations and how this country functions as an economy and as a democracy”. In reality, Thatcher was building herself an army as she and Ronald Reagan embraced a neoliberal model, dragging society kicking and screaming towards an increasingly globalised world with no sympathy for the casualties of occupational obsolescence. With the financial dissolution of so many working class families threatening her position, ‘Video Nasties’ became a convenient scapegoat for a “return to Victorian values”, scaring the public into voting against their best interests. It is sometimes difficult to gauge where the true horror lies.

Despite its political machinations, the furore surrounding ‘video nasties’ was very real, reaching almost puritanical levels at its frenzied peak. Whitehouse was particularly reviled by Raimi’s The Evil Dead, proclaiming it the “number one video nasty”, excerpts from the film screened at a special parliamentary session designed to publicly incriminate. It was around this time that local police began raiding distributors, confiscating and burning anything deemed dangerous. Top of that list was The Evil Dead distributor Palace Video, who were prosecuted before they were even able to assemble a legal team. It didn’t matter that video rental stores were found innocent of stocking the same film; someone had to pay, an example had to be made. Raimi was even called into court to protest the film’s innocence, the BBFC’s comparative lack of concern ultimately working in the filmmaker’s favour. The Evil Dead was finally removed from the ‘video nasties’ list in 1985 following additional cuts in conjunction with the 1984 Video Recordings Act. The fact that Whitehouse later admitted to having never seen the film was an astonishing instance of hypocrisy that typified the entire ordeal.

I first got my hands on a taped copy of The Evil Dead when I was around 10. How butchered that particular version was I can’t be sure because I didn’t make it past the first twenty minutes, but it must have been the UK’s 1990 release (that’s how long it took for distributors and the BBFC to agree on a suitable version following the whole Palace Video debacle). According to the BBFC website, the censoring body ‘was divided’ between those who felt that the film was so ridiculously ‘over the top’ that it couldn’t be taken seriously and those who found it to be ‘nauseating’. The original theatrical cut would suffer 49 seconds of cuts, including a reduction in the number of axe blows, the length of an eye-gouging and the number of times a pencil was twisted into Linda’s foot, with a further 66 seconds removed from the 1990 version. These are undoubtedly some of the most savage moments in the movie, the BBFC’s belief being that their omission would place more of an emphasis on those humorous elements, making it more palatable for the movie-going public, who were less accustomed to such flagrant violence at the turn of the 1980s.

It wasn’t until 2001 that The Evil Dead was finally passed uncut in Great Britain. By that time I was a little too long in the tooth to get frightened on any serious level, but one thing still rang true: despite the chaos and the political puffery surrounding it, The Evil Dead didn’t depend on its vile extremities. It was, and still is, filled with dread from the outset, a realisation that whisked me, rather unceremoniously, back to my childhood. As soon as Cheryl wandered into the dark recesses of the surrounding forest, I checked out completely as a 10-year-old. By that age I was already a seasoned genre fan who was fairly desensitised, but there was something queerly intangible about The Evil Dead that didn’t exist elsewhere. Whether it was the cheap reality of it all, the dizzying direction, the excruciating sound design or all three, after years of horror endurance, of bragging that I could take anything thrown at me, I had finally discovered a movie that lived up to the hype.

It was probably a good thing that I didn’t venture any further. The most notorious and talked about scene comes in the form of Cheryl’s merciless rape at the hands of the film’s sentient forest. Watching it back, I couldn’t believe how explicit and on the nose it still is all these years later. I’ve seen the movie dozens of times but it’s always new to me, as if I’m experiencing it for the very first time, and ‘experience’ is the key word here. The whole scene is painstakingly brutal, as if you’re being subjected to the whole protracted ordeal yourself. The movie may be dripping with irony and self-awareness for the most part, but then there are moments like this, the kind that sober you up like a firm smack in the mouth on a particularly frosty morning. The way Cheryl is wrestled into submission is enough to make you shrink with revulsion, and then there’s the act of penetration. Beautifully executed but utterly harrowing.

It is those scenes, juxtaposed with moments of giddy delirium, that lend The Evil Dead a seriously unique tone. The movie’s grand guignol visuals, as dated as they are all these years later, were a masterclass of resourcefulness back in 1981, and even now you can only sit and admire what Raimi and his crew achieved. It’s so easy to get that kind of thing wrong, especially for guerrilla filmmakers lacking the proper financial backing and the experience that it brings. In light of this, the comedy element is absolutely essential. There are plenty of reasons to be serious watching this movie, but when Raimi pulls the comedic trigger it has a kind of EC Comics vibe, albeit it a hopelessly possessed one.

Like the best, pre-digital indie horror outings, many of the film’s most inspired moments were the product of necessity, of thinking outside the box and acting on instinct, a process that inevitably had its share of unfortunate moments. Described by actor Bruce Campbell as a “comedy of errors”, The Evil Dead’s production was as calamitous as it was creative. On the very first day of shooting crew members got lost in the woods, several of them sustaining fairly severe injuries, the kind that were a nightmare to treat in such a remote location, and it didn’t get any more reassuring. Raimi’s eureka approach to direction called for several elaborate rigs to be crafted as cheaply as possible to substitute for the absence of a dolly, making the execution of many scenes unpredictable and precarious.

[singing] We’re going to get you. We’re going to get you. Not another peep. Time to go to sleep.

Linda

The movie’s most risky technical process, the kind that helped lift it out of the bargain-basement doldrums, was employed for those scenes where an ethereal POV presence races through the woods, a now iconic visual motif that is synonymous with a franchise with seemingly endless appeal. To achieve this, Raimi was forced to sprint through the hazardous terrain carrying one of those makeshift rigs, evading obstacles at full speed like a man leaping blindly into a gauntlet of endless booby traps. The film’s bravura final scene, which sees Ash taken out by that same pursuing presence, was shot with a camera mounted on a speeding bike that was driven through the ill-fated cabin and out into the woods. That moment, in particular, was an absolutely perilous one to capture, but boy was it worth it. Almost half a century later and it’s still as ferocious and as breathless as ever.

Other techniques were much more traditional. Possessed characters were caked in makeup, much of it rudimentary, but there’s no doubting the essence of evil captured by those pure white contact lenses, which, due to budgetary restraints, were as thick as Tupperware and immensely uncomfortable. Simple wires were employed for the animation of household objects and dismembered body parts. For special effects scenes, patience proved the crew’s biggest ally. One visual called for an actress to remain perfectly still for almost an hour while an expanding bruise effect was hand-drawn directly onto her leg. The film’s demonic climax employed already-dated stop-motion effects in an era of SFX sophistication. Hardly the basis for realism, but lovingly created and befitting of the movie’s often comic tone.

The financial and censorship limitations imposed on Raimi’s breakthrough picture would inspire his next horror splurge, a quasi-sequel titled Evil Dead II: Dead by Dawn. Two years prior, Raimi had tried his hand at straight-up comedy with 1985‘s Crimewave, a movie co-written by none other than the Coen brothers, but The Evil Dead‘s protracted banishment did not sit right with him, so he embarked on what is an almost like-for-like remake, placing a further emphasis on those comedic elements that the BBFC had pushed for. Dead by Dawn wasn’t self-censoring in the traditional sense. If anything it upped the splatter, but it did so in such a slapstick way that it was impossible to get offended. Many horror fans prefer the sequel, as well as the third movie in the eventual trilogy, Army of Darkness, which takes Ash’s battle to the middle ages in a left-field move that is in-keeping with the director’s predilection for off-the-wall creativity, but for me The Evil Dead stands tallest as both a feat of filmmaking and a cinematic artefact. In the annals of horror legend, its title is still uttered with an awed whisper.

The Evil Dead relishes in its ability to startle, to shock and exhilarate and ultimately disgust. When our cabin-bound girls suddenly leap from maudlin melodrama to pure, unadulterated evil, it absolutely floors you. The way those demons cackle and toy with the remaining survivors is excruciating to the point of giddiness, all of it buoyed by the kind of unyielding sound design that wears you down to a quivering nub. The scene in which Campbell mercilessly beats his possessed fiancé as she mocks him with her ceaseless cackling is a turning point for the previously loving Ash, and for we the audience. After that moment you yield to Raimi’s onslaught. You succumb to the feverish madness.

As an exercise in terror, very few dig their claws in like The Evil Dead. It grabs you by the throat and never lets go, Raimi force-feeding a platter of diabolical violence with the perverse delight of a hell-bound minion. The way he stalks his cast from behind pillars, an unseen presence lurking on the periphery of damnation, jumping from tracking shot to extreme close-up, and in the process transforming the super-animated Bruce Campbell into a bona fide superstar, is nothing short of breathtaking. And it’s all executed with such boldness, bravery and panache. Raimi grows in confidence as the evil does.

All of this leads to an astonishingly assured finale for a novice director. The nefarious wonderland that Raimi and editor Edna Ruth Paul create through frenetic cuts and skewed perspectives culminates in a blistering crescendo. Not only do you feel repulsed by the film’s gore-laden assault, you find yourself gorging on it like a zombie incredulously chomping on your very first brain. ‘Video nasties’ have garnered a reputation for being mostly cheap affairs that are worthless beneath their exploitative embellishments, but The Evil Dead isn’t one of them. In the realms of low-budget cinema it is a near-flawless outing; a worthy affront to anyone who considers themselves above this kind of fare. Despite the erroneous protests of portentous moralists, there is value to be found everywhere, and The Evil Dead is a grungy diamond buried deep in the recesses of censorship ignominy. I love its history, its sense of anarchy, the way it sheds the ‘video nasty’ stigma. It rose through a pile of mediocre garbage and planted a flag for independent filmmakers in the tradition of Romero, Hooper and Carpenter. It is rebel filmmaking at its finest.

Director: Sam Raimi

Screenplay: Sam Raimi

Music: Joe Loduca

Cinematography: Tim Philo

Editing: Edna Ruth Paul

I like how spooky and grimey “The Evil Dead” is; to me it has a heck of an atmosphere. The first time I viewed it I could hardly see it though, because the contrast was too low and I couldn’t do anything about it, but at the time it was an added element for me. When seen brighter, I enjoyed all the rustic details of the cabin. I like all the films in this series, but I always start in the beginning, and I hold this initial offering in high esteem.

LikeLike

Hi Eillio,

I have to agree. The Evil Dead is divinely grungy and a testament to human resourcefulness. It is rebel filmmaking of the highest order, and for me a minor masterpiece. Sure, the effects may have dated, but there’s something distinctly evil about it. Many prefer the sequel but not me. I respect Evild Dead II: Dead by Dawn but find it too overtly comical. You need that element of true horror and this one has it in spades. A grubby little artefact of cinema history that deserves all the plaudits and then some. A truly breathtaking feature debut.

LikeLike

Yeah, I agree, this film has it’s dark heart in the right place; really cruel and mean. Although I do like the sequels, I was surprised how self-aware and flip they are. All things being equal, I’d choose this Evil Dead due to the tension and what an emotional rollercoaster it is. And like you said, the effects are very good, especially considering the paucity of budget (effects aren’t the Holy Grail for me anyway, I’m more into mood, and I feel this film has some serious mood going for it).

LikeLike