VHS Revival contemplates the night HE stayed home and its ramifications on the series at large

When is enough enough? In an era of reboots, prequels and expanding cinematic universes, it seems that the answer is never. Horror sequels have been around in some capacity for almost as long as the genre has existed. The golden age of horror would open the proverbial coffin, monsters such as Dracula returning time after time to meet popular demand. If something is successful, let’s make more of it. It’s standard business practice.

Inevitably, people would tire of Universal’s revolutionary monsters, horror becoming commercially passé by the end of the 1940s, but the sequel template had been set, and Hammer Horror would soon take up the mantle, re-packaging Dracula and co and indulging us in a new era of returning characters as horror embraced the lure of gore and onscreen violence. Dracula, The Brides of Dracula, Dracula: Prince of Darkness, Dracula Has Risen From the Grave, Taste the Blood of Dracula, Scars of Dracula, Dracula A.D. 1972, The Satanic Rites of Dracula — coming up with a new title must have proven quite the headache for the decision makers over at Hammer.

Rather than continuing to think up an abundance of titles for returning characters, a new creative direction would become standard sequel practice, and I use the word ‘creative’ in the loosest possible sense. I’m writing, of course, about the dreaded numbered sequel. Excluding 1957’s Quatermass 2, a movie also known as Enemy From Space, the numbered sequel would begin in the 1970s, catching fire the following decade as the emergence of video tape led to a greater output of films. Interestingly, the first of those numbered sequels, Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather Part II (1974), is one of the few sequels that is actually considered to be superior to the original, a trend that would die a quick and brutal death as studios looked to cash-in rather than offer something new and rewarding. Throughout the years, a handful of sequels would be considered equal to or better than the original, but on the whole they are the exceptions that prove the rule.

By the late-1980s, sequels were not only everywhere, they were a given, particularly in the action and horror genres which dominated the home video market. For many low-budget filmmakers, sequels were a way to slash expenditure by saving on promotion and advertising. Thanks to the unbridled success of genre high-point Halloween, every Tom, Dick and Harry with a video camera was getting in on the act, investors queuing up at the prospect of stumbling onto their very own commercial goldmine. For those who were lucky enough to make a connection with the movie-going public, sequels were the next natural step, be that making a sequel yourself or catching the eye of a major studio and reaping the financial benefits.

You don’t know what death is!

Dr. Samuel Loomis

Perhaps the most plentiful franchise to come out of the VHS boom was the Friday the 13th series. A straight-up derivative of Halloween that would genericise the soon-to-be-ubiquitous slasher, the original movie would tell the story of Pamela Voorhees, a vengeful Norman Bates in reverse who slaughtered a gaggle of promiscuous teens after her son, Jason, was left to drown by a group of negligent camp counsellors. The movie was an unmitigated financial smash, raking in a whopping $59,800,000 on a budget of only $550,000, but for slasher fans it was the invincible masked killer who would prove the real breadwinner, a fact that saw Paramount dredge up the presumed-dead Jason for a copycat slaughterthon only a year later. For viewers who had been led to believe that Jason had drowned, this development was rather perplexing. Where had he been hiding since 1957? How did he eat, purchase clothes that fit his adult torso? How on Earth did he manage to suppress his pent-up bloodlust for almost a quarter of a century? All good questions, none of which were answered, but it didn’t matter. Paramount had the makings of their own money-spinning colossus, one who would slash his way into the hearts and minds of a generation.

Prior to mid-80s censorship hysteria and Jason’s descent into meta self-awareness, the slasher’s Golden Age, led by Paramount’s masked poster boy, would up the ante in regards to gore, relinquishing the patient foreboding of its biggest influence for who can top this bloodbaths that made the original Halloween commercially passé in the eyes of thrill-seeking teenagers, who embraced the era’s practical effects indulgence as a form of rebellion against disgusted parents across North America. In a post Summer of Sam, mid-serial killer boom environment of media-led desensitisation, kids had no problem with embracing human killers of the more relatable variety, and it didn’t matter how ridiculously generic the slasher became. Characters were applauded for their idiocy, their barefoot-in-the-woods contrivances allowing for the kind of commercial abattoir that kids flocked to see in their droves. For movie fans weaned on horror of previous generations, the slasher was indicative of the industry’s creative and moral decline, but money talks and evil walks, and so would the character who unwittingly sparked the dead-eyed killer revolution.

Carpenter, who would branch out into dystopian sci-fi with 1981’s Escape From New York, initially had no intention of making a Halloween sequel, despite the film’s ominous cliffhanger ending, but producer Irwin Yablans, looking to strike blood while the slasher’s commercially propulsive vein was still pulsating, managed to twist his arm. By the time the movie was released in 1981, Jason had already been unleashed on the cinematic wilderness, as had a seemingly endless parade of masked or heavily-scarred killers looking to make a dent in the market. Arguably the peak year for the slasher, 1981 would mark the release of My Bloody Valentine, The Prowler, Happy Birthday to Me, The Burning, The Funhouse, Hell Night, and a whole host of sub-genre cash-ins that would saturate the market and plant the seeds for late-80s censorship. So overwhelming was the sheer multitude of slashers at the turn of the decade that Student Bodies, released that same year, was a straight-up spoof which crudely lampooned the genre. Halloween II, it seemed, was somewhat late to the party.

Tonally, it certainly had a lot of catching up to do. Halloween‘s inspired use of space and shadows, particularly those foregrounds that are intrinsic to thrillers, resulted in a movie that is still considered one of the all-time classics of the horror genre, its slimline presentation and handling of the omnipresent ‘Shape’, along with Carpenter and Alan Howarth’s blood-curdling score, making the movie as terrifying in the drab palettes of the daytime as it is in the darkness of night, but much to the chagrin of Carpenter and collaborators Debra Hill, Dean Cundey and Tommy Lee Wallace, such an approach would no longer cut it. In order for Carpenter to keep pace with his imitators and meet audience expectation, Halloween II was forced to up the violence considerably, a scene in which Michael emerges from the darkness to plunge a hypodermic needle into the temple of an unsuspecting nurse being a case in point. Like much of the movie, it is rather well executed. It may pale to the original for a multitude of reasons, many of them unavoidable, but if you’re comparing Halloween II to the overabundance of like-for-like slashers that were flooding the market back in 1981, it ranks up there as one of the finest.

But this is Michael Myers we’re dealing with, and for many the bar should be set just a little higher, especially after it was decided upon that the sequel would be a direct continuation of the original movie in which events occur on the exact same night ― a risky move given Halloween‘s sparse, trimmed-down perfection. The film was originally set to take place a few years after the events of Carpenter’s original, Michael tracking Jamie Lee Curtis’ Laurie Strode down at her new home in a high-rise apartment complex, which in hindsight wouldn’t have been a bad idea. An apartment complex, as well as providing Michael with many victims of all descriptions, dodging the inherent contrivances of slasher storytelling, would have given the character plenty of places to hide, proving the perfect stomping ground for such a stealthy killer. In the end, Carpenter and company settled on Haddonfield Hospital during script meetings that Wallace, who would direct failed Halloween spin-off Season of the Witch a year later, claimed that “no one was all that excited about”.

Despite being a convenient by-product of Halloween II‘s decision to pick up where Halloween left off, the disconcertingly sterile and detached corridors of a hospital at night time is actually an inspired setting. After all, that’s where people generally go to die, allowing the film a degree of the irony that made Michael’s initial spree so rewarding, and there are plenty of nooks and crannies for the inimitable ‘Shape’ to inhabit as he looks to finish the job. Halloween II is also the closest we ever got to recapturing the POV style and mood of the original, thanks in large part to returning cinematographer Cundey, a budget that avoided the slick, realism-defeating sheen of later sequels, and the unwilling involvement of Carpenter himself, who though turning down directing duties in favour of first-time director Rick Rosenthal, would re-shoot several scenes after being left unhappy with what he later called “an abomination” and “a horrible movie”. Carpenter’s heart clearly wasn’t in the project from day one, and the final product did little to alleviate his fears it seems.

Despite a concerted effort to increase the violence, Halloween II also manages to retain Halloween‘s mood to some extent, but the ceaseless sense of foreboding and unrelenting tension are sadly absent. The main problem is that, in its heart of hearts, the film just isn’t necessary, and sequels in the same vein, particularly direct continuations of pitch-perfect movies, have sequelitis in their freely spilt blood. Unless you’re able to reinvent to some degree, those issues will quickly become apparent. This is especially true when you’re dealing with a mysterious character like Michael. In the original Halloween that sense of mystique was forged, purposefully and due to budgetary restrictions, with a distinctly less-is-more approach, and try as they may to stick to that formula, sequels are more by their very nature. As proven by decades of mostly underwhelming sequels across all genres, it is almost impossible to capture that original magic, especially when you’re dealing with movies like Halloween, an indie underdog that sprung up out of nowhere like a masked killer on the fringes of a wholly unprepared suburbia, quickly catching fire after an initial limited release exceeded all expectation.

One of the major downsides of a direct continuation is that, inevitably, characters from the original movie are unable to learn from their mistakes. In order for the screenplay to provide us with another 90 minutes of the same stalk-and-slash formula, familiar faces are forced into derisory predicaments. In the case of Halloween II, our cast senselessly isolate themselves in the aftermath of the worst multiple murder in Haddonfield’s history, which kind of puts you in Michael’s corner in a ‘you’re only getting what you deserve’ sense, offering an early glimpse at the killer-as-antihero formula popularised later in the decade. It is also necessary for the cops to become more negligent (just why was Laurie left unguarded at the hospital and drugged with Michael still on the loose?). Of course, if every character learned from their mistakes and applied just a little logic, the movie would be over before it even got going.

Then there’s the movie’s decision to suddenly make Laurie Michael’s sister, a development that was dropped from 2018’s reboot and subsequent sequels. It is hardly surprising given Blumhouse’s aim to restore credibility to the franchise, something that they failed to do in the eyes of many, particularly with the left-field shenanigans of Halloween Ends, which made Halloween 6‘s ‘Cult of Thorn’ debacle seem almost restrained by comparison. It just feels so unnecessary and tacked-on, a decision made in haste to sharpen the narrative blade and allow the sequel an added sense of bite. That kind of thing may fly with Friday the 13th, a gimmick-laden series that was transparently trashy from the outset, but Myers has too much lore to survive the same treatment, and there was already enough at stake given the original movie’s events. Surely a character like Michael, a borderline-supernatural entity drawn to murder as an inquisitive child, is scarier without extra motive, something that Carpenter and co were no doubt aware of from the beginning.

The characters that became so dear to horror audiences in Halloween also suffer in Halloween II. Initially unkeen on starring in Carpenter’s original until outstanding alimony payments forced his hand, Pleasence’s initial fears are realised to some extent in the sequel, even if his financial aspirations were more than met over the course of the series. Dr. Loomis is forced into regurgitated monologues that dilute not only Michael’s sense of fascination, but his own credibility as the movie’s harbinger of death. He’s not phoning in his performance. His heart seems to be in it even more given his familiarity with the cast and characters. It’s simply the nature of the commercial beast. There are only so many times you can hear that same old spiel before it becomes just a little repetitive. In Halloween II, it was passable, but by the time of Michael’s belated return in 1988’s Halloween 4: The Return of Michael Myers, the whole Myers/Loomis dynamic was verging on self-parody.

I also found it harder to invest in the Laurie character this time around, a fact that has less to do with Jamie Lee’s performance, more to do with the ingredients that combined to make her original struggles so heart-stopping. Halloween was imbued with a sense of community, a relatabilty that only added to the film’s troubling sense of reality, but the suburbia here is largely peripheral. Replacing Laurie’s ordinary, everyday friends are a cast of questionable doctors and nurses, the kind of groundless eye candy you would expect to see wandering around the set of Jason’s latest, and when a nurse takes time out from her shift to free her gigantic bosoms for a bout of late-night Jacuzzi frolicking, you may as well be back at Camp Crystal Lake. The teenagers from the first movie may have been thinly sketched and experimental in a way that damned them to the graveyard of slasher convention retrospectively, but they were identifiable, a fact that made the Myers character a more believable, vicarious threat. The absence of Tommy and Lindsey, the two questioning tykes whose ‘irrational’ fears about the film’s suburban boogeyman inevitably came true, also detracts from the Myers mystique. It was through that community and those characters that we were able to imagine those events happening in our very own neighbourhood, a killer like Michael appearing on the barely-lit fringes of our own suburban stronghold. It was fantastical yet tangible, fictional but not beyond the realms of plausibility.

Ultimately, it all seems just a little laboured. Technically, Halloween II has a running time of only 92 minutes, but since we’re dealing with a direct extension of the first film, it leaves you with a very different impression. The original narrative was horror perfection without an ounce of fat. It gave us just enough of Michael, a series of departing shots of seemingly innocuous Haddonfield locations forging the same unease that the character’s omnipresence and otherworldly sense of elusiveness inspired throughout. But three hours is too long for any horror movie, and that is essentially what we get when the two are combined. Despite the movie’s sense of restraint and adherence to the original Halloween formula in some instances, how long can we watch the same character being pursued on the same night before it all becomes meaningless?

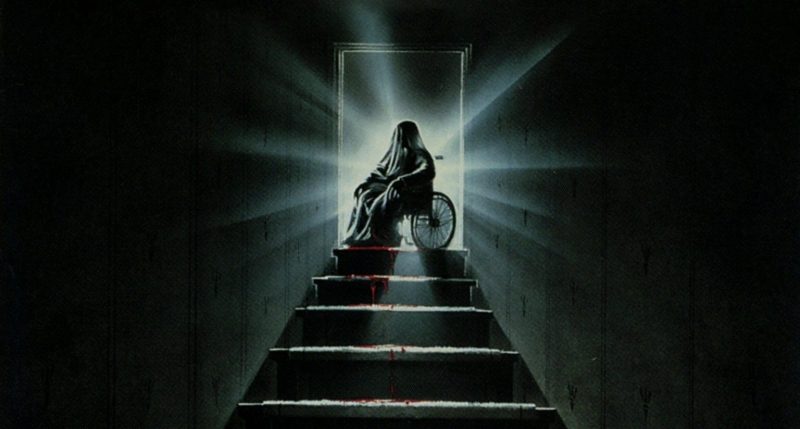

Even if you are a staunch admirer of Halloween II, and I do enjoy the movie as a fun, throwaway slasher, you have to question the logic of extending Carpenter’s original narrative in a way that transforms the whole experience into what could easily be viewed as a two-part mini series, such a direct extension and its impact on Halloween as a singular entity surely contributing to the sequel’s lowly status in a broader, mainstream sense. If the key to a rewarding sequel is maintaining certain elements while offering something fresh and unique, such a direct extension is the death knell for creative aspiration, Halloween II looking to finish what had already been achieved and then some. They managed to strike that balance with the equally brilliant promotional posters that were attached to each movie, which were similar yet strikingly distinct, it’s just a shame that the enthusiasm ended there. Maybe the original high-rise concept would have been more productive from a creative standpoint. Maybe Carpenter was simply past caring.

Why won’t he die?

Laurie Strode

As a standalone slasher Halloween II is an admirable effort in comparative terms, but the more we see of Michael the less engaging it all becomes, and this movie is entrenched in the original’s formidable shadow. Compare any slasher to the original Halloween and you are bound to dissect it to a pedantic degree, but this one doesn’t wind up in that shadow based on our affection for the first movie alone. It is submerged in it by being so closely related in terms of timeline. In the end, Rosenthal, Carpenter and Hill did all that they could to make a Halloween sequel to be proud of, but the act itself is enough to tarnish the Myers character, and in the end it just wasn’t necessary for any other reason than the financial, a point that Carpenter has been at pains to communicate ever since the movie’s release. There’s no getting away from the fact that Carpenter, a distinctly indie filmmaker who delivered his most inspirational work on the fly, never intended to revive his most famous creation. In Halloween, he made a movie that was supposed to be definitive. There’s a reason why he seemingly killed-off both Myers and Loomis so early on in the series.

But these things take on a life of their own — once a character or series enters the public domain it becomes public property. Myers is a force of super-nature beyond the realms of mere creative stalkery. People want to see the character in spite of the consequences. Producers tried to ditch him on two separate occasions, first with the delightful but commercially misguided Season of the Witch, which was set to become an annual event under the Halloween brand, but audiences just didn’t buy into it. Six years later they brought Michael back from beyond the grave for Halloween 4, another Jason-inspired effort that once again looked to replace Carpenter’s marquee killer with niece Jamie Lloyd, only for producers to backtrack with 1989’s Halloween 5: The Revenge of Michael Myers, leaving the character stumbling through the self-defeating alleyways of bizarre reinvention. Whenever they tried to push Michael out of the door, fan expectation and box office logic came knocking with a butcher’s relish.

For me, Halloween works best as a standalone film, and everything else, barring digressive anomaly Season of the Witch, proved superfluous, but do I resent the existence of Halloween II? Absolutely not. In the forty-plus years since its release, there have been plenty of instalments that have proven much more ridiculous and poorly devised/handled than Halloween II, the majority of them in fact, and, 2002’s wretched reality TV debacle Halloween Resurrection notwithstanding, I’ve enjoyed them all on some level. Even when the series fell into the bargain-basement doldrums during the mid-90s, I retained a degree of fascination for one of horror’s most emblematic characters. Halloween II‘s Michael is still a blast for the most part — single-minded yet patient, animalistic yet quietly intelligent. He is still the POV killer we know and love, still possessing some of the mystique that set the original Michael apart. We hear him breathing on the periphery. We see him dissolving into darkness or lurking in open spaces where he should be identified but isn’t. He is still an omnipotent force, effortlessly elusive and seemingly everywhere at once. There are moments here that could belong to the original instalment, but everything around him seems to falter.

In an alternate universe free from sequels, Halloween would still be considered a seminal, all-time classic, one that plays audiences like Hitchcock at his drollest and most technically inspired, but there’s no way Michael would have cut such a prominent figure in horror’s rich and storied history without them. We may have scoffed, we may have cringed as the character hacked his way through pagan cults, celebrity-based shenanigans and various other mythological weeds in the decades since the original film’s release, but many of us were first in line to see exactly how the character would evolve time and time again, even the most passive horror fan giving into curiosity eventually. That’s the beauty of a character like Michael. No matter how poor his handling, regardless of how impossible some of us are to please, we keep coming back for more, some with the quiet hope that a residue of that original magic will be recaptured, others merely to see their favourite horror icon unleashed on yet another unfortunate cast of characters who simply refuse to learn from past mistakes.

Director: Rick Rosenthal

Screenplay: John Carpenter &

Debra Hill

Music: John Carpenter &

Alan Howarth

Cinematography: Dean Cundey

Editing: Mark Goldblatt &

Skip Schoolnik

Likable Literary Treatise on Halloween II & sequels.

LikeLike

Thanks, Dale. Very kind of you. The Halloween series is a long (endless?) and intriguing saga, for better and for worse. I’ve committed myself to a marathon of the whole franchise once Halloween Ends hits theatres. Should be interesting. Particularly the order.

LikeLike