Exploring the legacy of one of horror’s great commercial coups

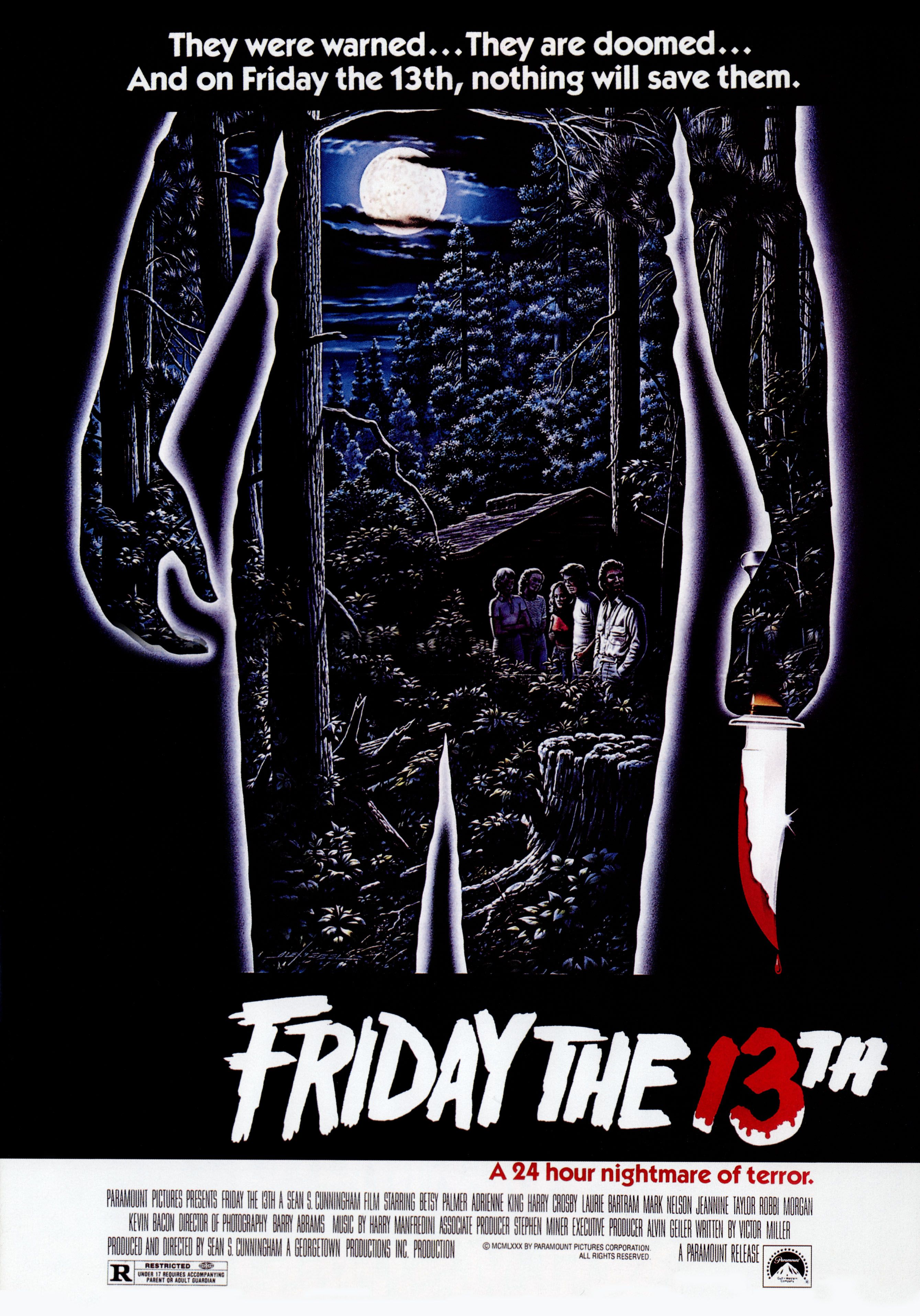

I find it telling that, whenever Friday the 13th rolls around, Sean Cunningham’s original summer camp slaughterhouse is one of the last instalments I consider reaching for. The reasons for this I will explore, but the one that stands a decapitated head above the rest is Jason Voorhees. Jason would first emerge as a secondary character, the victim of a tragic camp tale that proved fatal for a group of unfortunate teenagers looking to get their rocks off almost a quarter of a century after his supposed death. Thanks to the negligence of some highly-sexed camp councillors, a peewee Jason would succumb to the hazardous waters of Camp Crystal Lake, sparking one of the slasher sub-genre’s most memorable killing sprees.

That particular spate of murders was undertaken by someone that most people, at least back in 1980, would not have expected. The gender landscape has shifted rather dramatically in the decades since Friday the 13th‘s release, but the idea of a female slasher killer was still relatively anomalous at the turn of the 80s, particularly when cries of moralistic foul play put women firmly in the victims category. The concept of a female killer wasn’t exactly new. Strait-Jacket (1964), Frightmare (1974), Deep Red (1975) and Alice Sweet Alice (1976) had all featured female antagonists to name but a few, but when most people think Friday the 13th, they have only one killer in mind, and he’s wearing a hockey mask, not a knitted sweater.

Of all those female killers, Betsy Palmer’s Norman Bates-in-reverse, Mrs. Voorhees, is arguably the most memorable. Wild-eyed and deceptively vicious, the faux-motherly pretence used to lure final girl Alice (Adrienne King) into a false sense of security is still as creepy and perversely satisfying as ever, as is the savage, one-swing decapitation that abruptly curtails the madness ― a more than a fitting end for a woman pushed far beyond the realms of human compassion. Cries of sexism and protestations regarding the degradation of women would stalk the genre’s golden age like an unrelenting POV presence, so it’s ironic to think that one of the sub-genre’s most successful and universally recognised outings actually cast a middle-aged woman as the movie’s mystery antagonist. Along with the campsite setting and gimmicky title, it was Palmer’s against-type appearance, however brief, that made her the subject of nightmares across America and Friday the 13th one of the most talked about and financially fruitful entries in the entire genre.

“The imagination of the audience was teased nearly the entire time. You almost never see me kill anybody,” Palmer would say of her most famous role. “You only see the aftereffects of the murders. It’s your own imagination. That is what titillates and stimulates the viewer. When people visit me at autograph conventions and signings, they always say, ‘You just don’t know how you scared me!’ These people are grown up. They say, ‘When I was a kid, I just couldn’t sleep at night.’ Sometimes they will have babies with them. And they give me their babies, and they take pictures of me holding their baby. When we were shooting, I wore a sweater. I didn’t realize that it would become the iconic Mrs. Voorhees sweater. I have one now that is white, that is very reminiscent of the one in the movie. I wear it, and everyone thinks they are seeing the real Mrs. Voorhees. The audience just loves this woman. I have never been able to understand that. I ask them, ‘Why do you love her so much? Why?’ And they tell me, ‘We understand why you did it.’ My little background story leading up to my little boy drowning has affected these people. But this lady was psycho to begin with, I think. She just couldn’t deal with what was happening to her, and the death of her son pushed her over the edge. But she did it so that other children wouldn’t be killed. Or die.”

The movie itself has a similar effect on moviegoers of a certain age and predilection. The slasher was around in one form or another long before Friday the 13th, but it was certainly the film that popularised and ultimately genericised it, triggering a whole host of clones as the genre exploded in an abattoir of contrived nudity and creative slaughter. Some proto-slashers of note are 1960’s Peeping Tom (the first to utilise a POV killer), Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (the first instance of a weapon appearing to penetrate flesh, the result of George Tomasini’s deft editing process), 1971’s A Bay of Blood aka Twitch of the Death Nerve (the first to utilize a partial summer camp setting), and 1974’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (the first to feature a clearly delineated final girl). Though such movies were no doubt influences along with the giallo genre in general, they don’t tick all the boxes, either lacking some of the tropes or including others that discount them. For example, though A Bay of Blood features a mystery killer, a summer camp esque setting and a series of graphic kills with a blunt or sharp object, the killer is motivated by greed rather than a psychological twitch. When it comes to Americanised slashers, those murder mystery elements take a firm backseat.

Did you know a young boy drowned the year before those two others were killed? The counsellors weren’t paying any attention… They were making love while that young boy drowned. His name was Jason.

Mrs. Voorhees

Golden age slashers can be identified by the fact that the killer is typically a human, even if, like Michael Myers, they often possess a ubiquitous air which borders on the supernatural. Their motives, as mentioned, are usually pomological and/or triggered by notions of revenge/vengeance. Killers carry a deadly object that isn’t a pistol, typically racking-up an extraordinary body count in a number of extraordinarily violent ways. They typically stalk their victims in an identity-concealing point of view fashion and edge towards a final revelation involving a final girl. With this in mind, both Sergio Martino’s Torso (1973) and Bob Clark’s Black Christmas (1974), the latter becoming a direct inspiration for John Carpenter’s Halloween, might be considered the first out and out slasher. Halloween, which managed a whopping $70,274,000, was the one that made audiences and producers sit up and take notice, but it was Friday the 13th that made imitation a commercial artform. So successful was Cunningham’s original instalment that it famously sparked a bidding war upon completion, and was the first independent film of its kind to secure distribution in the US through a major studio. That’s no mean feat.

In the ensuing years, Friday the 13th would acquire a legendary status, standing shoulder-to-shoulder with superior mainstream efforts as one of horror’s giants, mainly because of the masked villain that was ultimately forged and the relentless run of sequels released during the 80s, but after all these years, does it really hold-up to such plaudits? There’s no doubting the film’s commercial status. The movie was easily the most profitable instalment of the series, managing an incredible cumulative worldwide gross of $59,754,601 on a budget of approximately $550,000. Much of the film’s success can be attributed to Halloween, a similarly low-risk venture that paid dividends, inspiring a struggling Cunningham to call up screenwriter Victor Miller and unashamedly suggest, “Halloween is making incredible money at the box office. Let’s rip it off”. The budding filmmaker/producer barely had a premise at the time, just an incredibly marketable title in the holiday horror mode. One thing that wasn’t necessarily considered in an era of franchise naivety was the possibility of a sequel. There was no way Cunningham could have gauged just how successful the film would be. When Mrs. Voorhees died, it kind of killed the series from a narrative perspective, but the mayhem was only just beginning.

Though Jason had supposedly been dead for many years (how he was able to survive in the wilderness for so long is anyone’s guess), Paramount were looking for a marquee killer that they could unleash on a regular basis, dredging him from the legend of Crystal Lake on May 1, 1981. After the comparative box office failure of My Bloody Valentine, released as a stopgap to cash-in on the genre’s popularity earlier that year, the company’s goal was to forge a masked killer very much in the Myers mode who teenagers could buy into. Jason’s initial outing, as memorable as it was, was very much a transparent derivative that stuck stringently to the golden age slasher formula, but as the years transpired the character would become an entirely different entity, an amoral antihero more concerned with clocking up a kill count than offering any genuine scares. With Jason as the sub-genre’s poster boy for moral outrage, horror was no longer about peeping through your fingers in fear. It was about getting loaded and cheering on the murderer, buoyed by the thrill of seeing just how brutal affairs could get. By the time Jason was in full swing, dear old Pamela was but a distant memory.

The Mrs. Voorhees character would make other appearances down the years. Part II would display her mutilated head in Jason’s backwoods hideout, final girl Ginny Field slipping into the now world-famous jumper and impersonating her as a means to bamboozle a cockheaded Jason, leading to the first of many supposed deaths for our soon-to-be indestructible brute. Part 3 would feature a bizarre dream sequence-come-homage that saw Pam’s mummified corpse leap from the muggy waters of Crystal Lake, supposedly dragging final girl Chris Higgins (Dana Kimmell) down with her in a nod to the original film’s false ending jump scare. More recently, Fred Krueger would assume her form in the dreamworld as a way to confuse the hulking brute cherry picking all of his victims in 2003’s Freddy vs Jason. This time Palmer herself would return to the role in a movie that very much thrived on nostalgia, but the character was already a distant memory barring everything but the occasional reference by 1982.

It’s a rare occasion that the first instalment of a series slips so far down the pecking order since they’re typically the most memorable and critically relevant. That’s not to say it’s no longer a favourite among fans, but the property has been stuck in legal limbo for years, the most recent instalment of the franchise, a 2009 reboot which reinvented the Jason character as a more realistic survivalist killer, alluding only briefly to the Mrs Voorhees character. The original Friday the 13th will always be the go-to instalment for a certain generation, introducing a summer camp setting redolent of campfire urban legends that they could fully relate to, but in all honesty it hasn’t aged too well. Some of those sequels haven’t aged too well, either, but the genre would grow self-aware by the middle of the 80s thanks to the censorship impositions of the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), and Jason’s instalments were never more than trash cinema while the original instalment remains one of the most famous horror movies in the history of the genre.

The original Friday the 13th is held in such high esteem that you can’t help but feel just a little disappointed. At the time of its release it was still somewhat fresh and unique, at least in the US mainstream, but the sheer deluge of like-for-like slashers forged in its wake has left it floundering all these years later. There’s very little to distinguish it as an innovator asides from its influence as a successful imitator, and unless you experienced it first-hand back in 1980, it’s pretty unremarkable in the realms of slasherdom, which would produce zanier, more violent, more creative films, particularly after the genre embraced the censor-dodging realms of the supernatural (though the onscreen mutilation of a real-life snake with a machete makes for quite uncomfortable viewing well into the 21st century). I still enjoy the movie, but it doesn’t possess the elusive mystique of Halloween, the game-changing qualities of A Nightmare on Elm Street, the startling violence of The Prowler or even the unreserved madness of a more traditional golden age slasher like Pieces. It has a nostalgic charm with its throwback aesthetic and a series of memorable kills dreamed-up by the inimitable Tom Savini, which were absolutely brutal for the time, but Jason has become so synonymous with the series that it almost feels like there’s something lacking. I’m sure younger generations who came to the franchise late were surprised to discover that Jason wasn’t the killer from the beginning.

Ironically, the original Friday the 13th remains one of the goriest instalments of what would prove a mostly bloodless series. Those who are familiar with Jason’s exploits will understand exactly what the majority of the franchise represents. The blueprint slasher would suffice for two instalments, director Steve Miner opting for the peephole pillowcase as an interim mask as the series further defined itself. Friday the 13th Part III, which would resort to the short-lived Reagan-era 3-D fad to combat waning returns, would prove both the bloodiest and silliest instalment to date, procuring the iconic hockey mask and bringing Jason out of the POV shadows towards antihero territory. While every instalment suffered at the hands of the censors to some degree, Friday the 13th Part IV: The Final Chapter, though reneging on its series-ending proclamation less than a year later, would prove just that in terms of creative violence. All these years later, we can see those first four instalments in their uncut forms. Beyond that, Paramount became self-censoring, much of the edited material that followed lost forever.

Beyond Part III’s ludicrous flirtations with ‘A New Dimension of Terror’, Paramount would turn to all kinds of gimmicks to keep the series relevant: a fan-dividing copycat killer, telekinetic Carrie clones and even a brief, cost-cutting trip to Manhattan in what proved the death knell for Paramount’s shameful love affair with stalk and slash returns. Some of those later instalments, for reasons creative and financial, were really scraping the barrel, directors running into all kinds of problems with executives whose only goal was to squeeze every last drop of blood out of their fruitful, low-cost venture while simultaneously condemning it to the cutting room floor. When New Line Cinema, having long-flirted with the idea of a Freddy vs Jason crossover, eventually bought the rights to the series with a view to producing a horror icon death match, body-swapping journeys to hell and space-bound slayings would be added to the menu of bizarre hors d’oeuvres designed to keep the punters coming back. Which they did. Barely.

Perhaps even more of a draw than the annual gimmick was seeing just how creative Jason would get with his favourite pastime, and as the series narrative became more and more dubious, exploring multiple timelines and bumbling through all kinds of continuity issues, how in the hell he’d manage to return from the brink this time around. During his tenure, Jason was stabbed, hung, slashed, shot, melted, set on fire, blown-up and buried alive, and each time writers found convenient and highly dubious ways of explaining his return. Because of the seemingly inexhaustible longevity of the franchise, silliness had become a part of Jason’s charm, the character transformed into a mindless meta villain for the MTV generation.

Come, dear. It’ll be easier for you than it was for Jason.

Mrs. Voorhees

When Wes Craven revived the moribund slasher in 1996, our relationship with the sub-genre was all but confirmed. The hugely popular Scream would not only revamp stalk-and-slash depravity for a new generation, it would shine a self-reflexive light on events, sending a not-so-subtle wink to those weaned on the likes of Jason Voorhees. Those audiences were now approaching middle age, could appreciate a cast of informed characters foreshadowing their own deaths based on the predictability of the genre. Tellingly, there’s a moment in Scream that reaffirms the theme of this article. When Drew Barrymore’s character, Casey Becker, is forced to answer a series of horror movie questions in order to prevent the death of her boyfriend from the slasher-obsessed fury of the genre’s latest marquee killer, she’s asked to name the killer in Friday the 13th. In her haste, she calls out, “Jason!” By the time she’s realised her mistake, it’s too late.

The fact that Friday the 13th took such precedence in a movie about the horror genre at large proves the extent of its legacy, but its place there is rather tenuous. As a textbook stalk-and-slash, the movie is a fairly tense affair, with patient POV builds and a genuinely refreshing twist. It also features a superior Herrmann-esque score that plays with your nerve endings like a rusty cello, the world-famous ‘ch ch ch, ah ah ah’ soundbite, later confirmed as ‘ki’ and ‘ma’, an abbreviation of Palmer’s line “Kill her, mommy!” whispered into a microphone and fed through an Echoplex machine. If it wasn’t for that creative eureka, inspired by the consonant-heavy Polish scores Manfredini was studying at the time, it’s unlikely that the original Friday the 13th would have been half as influential. Manfredini would tinker with the ‘Friday’ theme throughout his tenure, even producing a whacky, disco-infused variation for Part 3, but this is the version most entrenched in conventional horror, often elevating events above low-budget mediocrity.

Ultimately, Friday the 13th shares a lofty vantage with films that are much more unique and inspirational. That inspirational summer camp setting, a staple of the sub-genre going forward, notwithstanding, it is less an innovative filmmaking exercise, more a feat of commercial chicanery that borrows sparingly from just about everything. As well as taking cues from A Bay of Blood and Halloween, the shadow of Hitchcock looms large. The imagined connection between Pamela and her fallen offspring, though a transparent imitation of the one Norman Bates shares with his deceased mother, is executed rather wonderfully, and in local ‘lunatic’ Crazy Ralph, Cunningham even throws in the fabled Hitchcockian harbinger of death, a character whose vocabulary seems to stretch no further than cliched forewarnings such as, “We’re doomed, I tells you!” With a plethora of horror ingredients hand-picked from the tree of established success, what Cunningham delivered was a pastiche that ticked all the commercial boxes for rebellious, post Civil Rights teenagers flocking to the theatres in their droves. However second-hand Cunningham’s master plan, he stole from the best and managed to pass it off as something fairly original. For such a low-budget and transparently derivative outing, the movie has achieved an incredible degree of stature.

[high voice] Kill her, Mommy! Kill her! Don’t let her get away, Mommy! Don’t let her live! [normal voice] I won’t, Jason. I won’t!

Mrs. Voorhees

Friday the 13th does have its own strengths other than the ability to steal. The film benefits from a superior cast at a time when acting ability was still fractionally more than peripheral, the likes of Kevin Bacon getting his start here. There’s also some admirable cinematography from the late Barry Abrams, who helped create the kind of desolate, leafy retreat generations could relate to, but the movie’s real strength lies with Tom Savini and a series of grisly, largely uncut murders that would set the tone for a decade of Jason-led brutality. Axes in the face, spears through the throat, arrows protruding from every orifice imaginable; it was all quite the novelty back in 1980, and for American teenagers a taboo outlet that provided vicarious thrills with an anarchic twist. According to Making Friday the 13th: The Legend of Camp Blood by author David Grove, Cunningham wanted his picture to be ‘shocking’ and ‘visually stunning’, and for the most part he succeeded.

As a traditional exercise in slasher filmmaking, the original Friday the 13th is more effective than the majority of the franchise, but despite their shameless lack of artistry, those Jason-led instalments are much more distinctive. With Jason, Paramount created a marquee attraction who would outlive the era that forged him. A Nightmare On Elm Street and Halloween would both tread similarly farcical ground as the genre lurched towards early 90s inanity, the latter ironically borrowing from its biggest imitator by upping the kill count to adapt to commercial trends, but ask anyone for their favourite entry in those franchises and most will opt for the original. Conversely, nothing divides opinion quite like the Friday the 13th Franchise. Ask fans to give you their favourite instalment and see how surprised you are. This was only confirmed by the response we got to our own series ranking. Our readers may not have agreed with the final order, but there were no complaints either, even when the original Friday the 13th came in at a lowly fifth.

For all the reasons explored, the original Friday the 13th has become something of a series outlier. This is less to do with traditional notions of quality, more with the evolution of an inexhaustible series that would grow into a very different entity with our masked attraction at the helm. The original may have been a box office titan that dwarfed even the most successful Jason-led instalments (adjusted for inflation, the movie would have raked in somewhere in the region of $190,000,000 on a budget of $1,500,000 in 2022), but Pamela’s initial killing spree doesn’t immediately leap to mind when you think of the Friday the 13th series. It was enough to get Cunningham’s foot through the door, but for a producer with aspirations of establishing an annual, money-spinning franchise, something more was needed, and that something came in the form of Jason.

Characters like Freddy and Jason are so beloved, are discussed in such scholastic detail by genre die hards, that producers would pit them against one another long after the slasher craze had settled, fully aware of the concept’s box office power. The likes of Mrs Voorhees could never qualify in that regard, but next time someone asks you which of horror’s commercial behemoths would win in a fight, please spare a passing thought for Pamela, because without her there would be no Jason, and who in the world would want that?

Director: Sean S. Cunningham

Screenplay: Victor Miller

Music: Harry Manfredini

Cinematography: Barry Abrams

Editing: Bill Freda

Fantastic and very insightful retrospect about Mrs. Voorhees. It is strange how the character, indeed the original Friday 13th, has become so ingrained in Pop Culture yet also bizarrely overlooked now in so many ways. Mrs. Voorhees remains a pivotal aspect to the franchise, however the characters hardly been revisited much at all. The original Friday 13th film is one of my all time favourite horror films, its a classic, and a movie that helped define the genre – and in many ways its influences are still felt even today.

LikeLike

Thanks, Paul. And thanks for taking the time to read as always. It’s a bit of an anomaly, isn’t it, that such a high profile movie would become something of an also-ran, along with Pamela, because of Jason’s iconic status.

I’m still waiting for the Mr Voorhees sequel. She was clearly demented beyond the vengeance she sought. Just imagine the possibilities. Who knows what she’d get up to in her youth on the fringes. And what about Jason’s father, presuming she didn’t kill him first.

Hopefully when all the legal nonsense it sorted out we’ll get a fresh and unique take on the series. And who better than the maniac in the knitted jumper who started it all.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I certainly hope all that legal red tape can get sorted and we see more of Mrs. Voorhees, there’s such a wealth of possibilities to explore with the character.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Here’s hoping. I can definately see it happening in today’s horror climate. The only question is casting. Who would you cast as Pamela?

LikeLiked by 2 people

Oh blimey, that would be some difficult casting indeed. The role is so iconic, it’d take someone really special to capture the same kind of menace.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Palmer was so against type too, having been America’s smiling darling beforehand. That would be almost impossible to replicate.

LikeLiked by 1 person