VHS Revival locks and loads for Luc Besson’s stunningly effective, if somewhat problematic action thriller

Of all the movies to come out of the hip, dysfunctional 90s, few were as enigmatic or as thematically polarising as Luc Besson’s US debut Leon: The Professional, a film that treads a tenuous line between mildly inappropriate and severely disconcerting against a backdrop of intense, captivating, often spellbinding cinema. The first time I experienced the movie I was roughly the same age as its Nabokovian protagonist, a twelve year-old Natalie Portman igniting the kind of emotions that skip tenuously around Leon‘s troubled core. As a child myself, I didn’t see anything particularly odd about a movie that tackles sensitive themes in a strangely beguiling manner, partly because I had such a palpable crush on a character caught in a queer purgatory of adolescent naivety and world-weary adulthood, and partly because I rented the 110-minute theatrical cut, which does away with 25 minutes of footage that stumbles rather awkwardly for the most part, bringing the film’s otherwise pristine presentation to a jarringly contemplative halt.

All these years later, though equally beguiled and even more impressed from a filmmaking standpoint, I was left pondering a single question: would Besson’s film, known simply as The Professional on US shores, have seen the light of day in today’s hyper-sensitive, hyper-informed society? It’s doubtful, particularly the filmmaker’s extended version, otherwise known as the “international version”, “version longue”, or “version intégrale”, which, for reasons that will become clear, scored rather poorly during initial test screenings, turning a near-perfect movie into a somewhat problematic action thriller that undoes some of the screenplay’s indecorous but largely considered nuances like an arthritic pensioner fumbling with a pair of hopelessly frayed laces. It is worth experiencing both versions, simply as a reminder of how important the editing process is and how fragile an otherwise flawless work can be if even remotely mismanaged, but the theatrical cut remains one of the most unique, intriguing and beautifully executed films of the era.

That’s not to say those deleted scenes are completely devoid of value. From a storyline perspective they make perfect sense, but their handling is far less considered. Léon focuses on two lonely, disassociated citizens of an unforgiving New York City. Both are trapped in environments that are almost completely devoid of compassion, both are looking, unconsciously or otherwise, for a reason to live beyond unbearable routines that are fraught with tension, violence and an unyielding sense of danger. Both are caught in emotional traps that, for one reason or another, are almost completely inescapable, lives which fate would have it are occurring within five metres of each other in a rundown apartment block in Little Italy, a place where crime quietly thrives in the mobster traditions of Martin Scorsese.

There are differences, however, startling differences. Jean Reno’s Léon is a middle-aged Italian (though incredibly French) hitman living out of a suitcase, one bursting at the seams with an array of automatic weapons and the kind of skeletons that not even Narnia’s dizzyingly expansive wardrobe could contain. Portman’s Mathilda is the unloved child of a fractious family unit of crime-flirting stepfathers, ditzy stepmothers (an incredibly sexy Ellen Greene of Little Shop of Horrors fame) and abusive stepsisters, a girl old beyond her years who still retains enough naivety to make her unwilling saviour, a man more than comfortable on society’s amoral fringes, deeply uncomfortable. Their union is sweetly dysfunctional but fundamentally wrong, red flags popping up all over the place. When a concerned hotel manager, responding to a besotted Mathilda’s claims that Léon is in fact her lover, not her father as she had first misinformed, arrives to enquire about the pair’s living predicament, he echoes the concerns of an audience that continuously slips in and out of uneasiness.

Leon, I think I’m kinda falling in love with you.

Mathilda

The differences between the theatrical cut and its troubled half sister are minimal but startling, appropriate to the context of the piece yet wildly inappropriate for a movie that fundamentally sets out to entertain. It is more than believable that such a misguided and maltreated girl, racing towards the hormone-fuelled highways of adolescence, would find comfort and even a sense of unhealthy attraction in an adult saviour, but such themes are usually reserved for downbeat material that clings to the shadows of ugly, hard-to-digest realism. Here it gingerly hugs the fringes of quirky European dramedy and comic book violence, a heady brew that is as intoxicating as it is unsettling. Even the theatrical cut jars on occasion. The fact that Léon is in many ways just as gullible as his peewee companion lightens the burden, the hormonal Mathilda understandably besotted with a saviour who shows her affection in a way that is boyishly endearing, but it still touches a raw nerve, particularly when Leon gifts Mathilda a dress that she duly models, sexualising the young actress to an uncomfortable degree. Reno, who consciously plays Léon as an emotionally stunted child in a man’s body, would allow Portman to control the emotional tone of such scenes. Realising the tenuous nature of the material, he didn’t want his character to pose a sexual threat to Mathilda, and, crucially, he never does.

The extended cut is much more on the nose thanks to a selection of second act scenes that see Mathilda falling headlong into the realms of infatuation. They also place her in violent situations that prove similarly uncomfortable, somewhat marring the paternal nature of her relationship with Léon, which proves essential for ironing out the film’s vaguer elements. One particular scene sees Mathilda swilling champagne in a restaurant, her misguided sexual desire frothing to the fore like a precariously popped cork at a playdate tea party. She also broaches the subject of her feelings in no uncertain terms, forcing Léon, who typically sleeps sitting with one eye open, into sharing a bed with her, positioning him like a loving husband in a night time clinch. Mathilda has no experience with paternal affection, nor does her initially reluctant saviour. It makes for a compelling if somewhat discomposing viewing experience.

Typically speaking, extended cuts mostly affect pacing, and while that’s also the case with Leon, the problems run deeper. While the theatrical cut takes a more gentle and juvenile approach to an unfortunate situation, the extended cut reveals all of its cards in a way that sullies the narrative along with the integrity and likeability of its characters. We also follow the pair through a series of assassinations that not only corrupt Mathilda, a girl still reeling from the brutal massacre of her entire family, but place her recklessly in harm’s way. Those scenes also impact the significance of the little things. In the extended cut Mathilda wears a hat and shades that are almost identical to those worn by Léon throughout those scenes. In the theatrical cut she only dresses like a hitman during a misguided act of vengeance that’s beyond Léon’s control. It may seem like a small detail, but film, like all art, is all about the small details, and it makes a huge difference to the film’s central relationship. It’s those moments, chosen sparingly, that you remember when the narrative smoke clears.

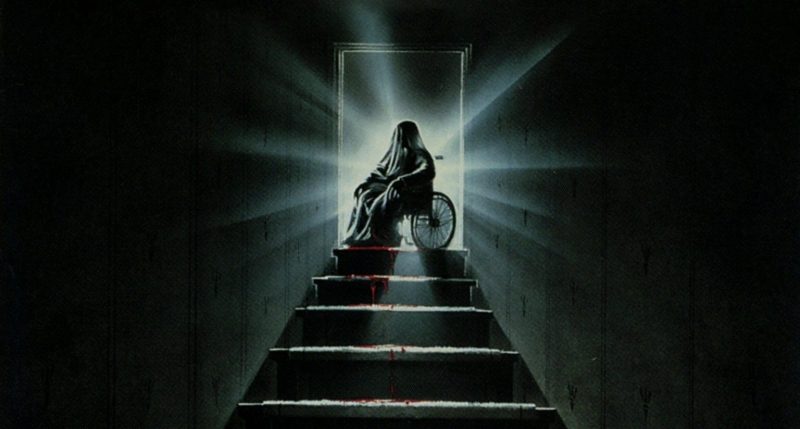

The theatrical cut is almost pitch-perfect. The opening scenes are all about Léon the meticulous killer, Danny Aiello’s contract-serving mobster reflected in the mysterious glare of his shades. That single image says a lot about Léon’s approach to working life, about his disassociation from everyday reality, common law and traditional ethics. Aiello’s savvy mobster, though clearly fond of his enigmatic employee, exploits Léon’s regular world naivety when it comes to money. He also influences his daily routine, keeping Léon on the move and friendless. The aim is to keep him sharp and focused, motivated not distracted, something we get a first-hand look at during the film’s incredible opening Salvo, Léon picking off a gang of mobsters with unflinching professionalism and emotional detachment. Dressed in his trademark hat and sunglasses, Léon has the splash panel Illusiveness of a Marvel superhero, emerging in and out of the darkness like an omnipotent slasher villain with otherworldly abilities. It’s all so frantic, claustrophobic and inevitable. When he shows up at your door, you’re pretty much done for save for an act of mercy on his employer’s part.

The rifle is the first weapon you learn how to use, because it lets you keep your distance from the client. The closer you get to being a pro, the closer you can get to the client. The knife, for example, is the last thing you learn.

Léon

Those scenes are more in-tune with Besson’s newfound American audience, but elsewhere the filmmaker relies heavily on his experience in European cinema, giving the Léon character and the environment he exists in a fantastical edge that’s absent from most US action thrillers of the era. At times Leon’s maladjusted existence plays out with the tragicomedy of a vaudevillian street performer. Away from the ruthless despotism of his rifle, he has the harmless air of a lovelorn boy from a remote French village, sporting drainpipe trousers that could be tied in place with a length of rope. Fittingly, and perhaps as a consequence, Besson is able to capture New York City from a truly unique perspective, Leon’s fish out of water idiosyncrasies beautifully at odds with a city renown for playing host to all walks of life. Léon, a character who appreciates the vastness and anonymity of life in the Big Apple, is more than just an emotional outsider. Like the Golden Age musicals that bring him so much vicarious joy, it feels like he belongs to an entirely different era.

Despite the unflinching way in which he approaches those opening moments, there’s a human side to Léon that’s glimpsed long before Mathilda’s bruised seraph drifts unceremoniously into his life, one that goes beyond the killer’s strict mantra of ‘no women, no kids’. Away from watching eyes he regresses into a state of childlike wonder, retreating to the solemn, smoky shadows of an afternoon matinee where the innocent pleasures of Gene Kelly offer a much needed dose of escapism. After Mathilda arrives on his doorstep, fighting back tears as the brutal slaying of her family unfolds, that side is only awakened further, Léon performing pig pantomimes with the gusto of a circus master or partaking in childish water fights in the confines of their austere kingdom in the murky corners of the city. Mathilda, who offers to pay Léon to take out her family’s killers, finally demanding that he train her to do the job herself, becomes both his strength and his weakness, someone to nurture beyond the solemn plant that rests peacefully on his sun kissed windowsill while raising the emotional stakes, causing Léon to break routine and become sloppy, at least by his punctilious standards. A glass of milk becomes a bottle of celebratory champagne, non-interaction with outsiders becomes a protective outburst on the doorstep of his employer, a life of self-preservation becomes the unconditional preservation of another. In short, Mathilda changes Léon irrevocably, and you fear that it’s only a matter of time before he slips.

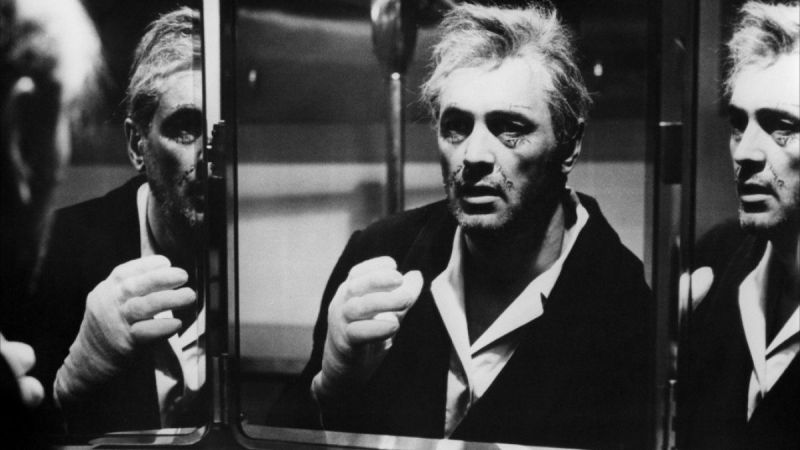

Produced by the now defunct Les Films du Dauphin on a budget of $16,000,000, Leon: The Professional‘s central cast is small but fearsome. A year on from his outlandish turn as dreadlocked pimp Drexl in Tony Scott’s Tarantino-penned True Romance, Gary Oldman plays it to the absolute hilt as the man responsible for Mathilda’s life-changing shot of misfortune, a corrupt cop who pops pills with a perverse sense of grandeur, orchestrating gruesome massacres with the whimsicality of Beethoven’s 8th Symphony. The movie’s awkward central relationship may flirt with the grossly perverted but Oldman’s Stansfield is a miscreant of the highest order, a man who guns down teenagers with the insouciance of a mildly inebriated devil, barely flinching after Mathilda’s four-year-old brother catches a fatal stray bullet. Later, after stumbling onto Mathilda’s bold assassination attempt, he asks, “What filthy piece of shit did I do now?” Showing absolutely no remorse for the death of her brother, he then says, “I take no pleasure in taking life if it’s from a person who doesn’t care about it.” Stansfield is wicked, unruly and above the law, even strong-arming Aiello’s Tony after getting wind of Leon’s impending threat. In an environment of deeply dysfunctional characters he’s a bottomless deviant with absolutely no peers.

Aiello is equally beguiling in a more understated role, effortlessly assuming the guise of savvy, world-weary gangster, a man mired in crime and motivated by greed and deception who has a half-buried affection for Léon that goes beyond man-management and personal prosperity, but a startlingly accomplished Portman steals the show with a performance so precocious, nuanced and resourceful it’s almost scary. In many ways, Léon: The Professional is a slightly tweaked variation of Besson’s 1990 smash La Femme Nikita, Anne Parillaud’s misanthropic teenage-junkie-come-programmed assassin replaced by Portman’s emotionally conflicted orphan. The notion of a preteen assassin, a concept much more at home in the realms of stylishly violent manga cinema, may have seemed fanciful, unrelatable and borderline ridiculous in the hands of a lesser actor, but Portman is never less than convincing as a child burdened by the hardships of a dozen lifetimes, walking a tightrope between instinctive adolescent exuberance and irrevocable adult corruption. The emotional range and complexity she brings to the character is nothing short of phenomenal.

If the film’s second act recalls the quirky aesthetics and ironic presentation of European cinema, then its stylish, action-packed finale is Hollywood at its finest, adding mainstream appeal to material otherwise suited to the realms of arthouse indie drama. Holed-up and under siege from a hit squad unwisely using Mathilda as collateral, Reno’s one-man army somehow turns the tables, using his particular set of skills to singlehandedly wipe out Stansfield’s corrupt rabble and reclaim the only living person who brings meaning to his life. Their final moments together and the heartbreakingly improbable proposition of reunion are absolutely palpable, Portman going above and beyond during the film’s most captivating moment, Léon’s act of heroic selflessness eradicating all notions of improper conduct. The gut-wrenching division of two co-dependent souls with no identifiable place in the world beyond each other’s company lends those action scenes, orchestrated with explosive aplomb, an extra dimension amid the conventional chaos. It’s a beautiful, tragic, emotionally fitting end to a uniquely passionate relationship that’s unseemly beyond their bubble of dysfunction, and as a consequence could never last.

I don’t give a shit about sleeping, Leon. I want love, or death. That’s it.

Mathilda

The film’s explosive pay-off is similarly tragic in a traditional sense, Léon’s crafty, almost successful escape attempt garbed in the bloody combat gear of one of his victims curtailed by Oldman’s wily predator, who fittingly shoots the film’s titular assassin in the back like a coyote gnawing on the remains. In reality, Stansfield has walked into a trap, Léon handing him the pins of a chest-full of grenades, his parting gift to the young girl who brought temporary joy to a life of unbearable solitude. That moment, which in-line with Besson’s dark sensibilities was supposed to be the work of Mathilda herself, is the cathartic release that Léon craved, the key to eternal freedom that could never be achieved on Earth. Mathilda may have given him purpose, but as his final interactions with Tony reveal, he knows it’s only a matter of time before his profession catches up with him. Like the window plant that soaks up the slithers of sunlight creeping through the New York City metropolis, Léon tasted the intoxicating warmth of human compassion but could only grow so far. Ultimately, his redemption lies not with personal growth, but with the growth of a troubled soul who still has time to blossom the right way.

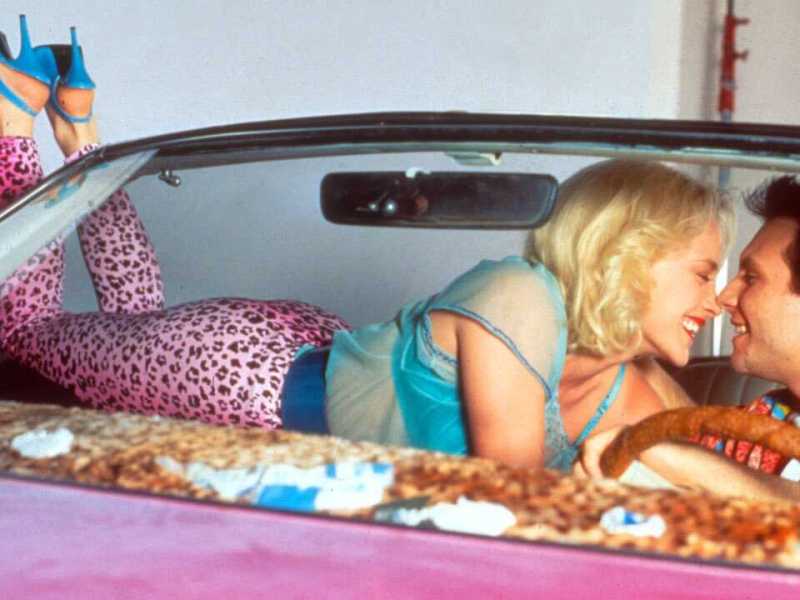

As compelling as the theatrical cut is, the extended cut, the director’s true vision, remains a deeply disconcerting watch that raises questions about Besson, particularly in light of real-life events, which seem to throw-up an unseemly instance of art imitating life. Child actress Maïwenn, who appears in the film’s opening scenes as a gangster’s call girl, was the same age as Portman’s Mathilda when she met Besson, who was twenty-nine at the time. The two would enter into a romantic relationship when Maïwenn turned fifteen (the age of consent in France), the two conceiving a daughter less than a year later. “When Luc Besson did Léon, the story of a 13-year-old girl in love with an older man, it was inspired by us since it was written while our story started. But no media made the link,” Maïwenn would claim. “I had my daughter very young, so I had fulfilled my dream, and then… he left me. Everything then collapsed for me.” Maïwenn would even write a book about her relationship with Besson and life rubbing shoulders with the stars of Hollywood, banning the publication after the publisher promoted it as the saucy exploits of a real-life Hollywood Lolita.

Portman herself, who became a teenage pin-up almost overnight, was equally candid about her early sexualisation and the effect it had on her growing up as a high-profile celebrity. “When I heard [Hollywood’s sexual allegations] coming out, I was like, ‘Wow, I’m so lucky that I haven’t had this.’ And then, on reflection, I was like okay, definitely never been assaulted, definitely not, but I’ve had discrimination or harassment on almost everything I’ve ever worked on in some way. I went from thinking I don’t have a story to thinking, Oh wait, I have 100 stories. And I think a lot of people are having these reckonings with themselves, of things that we just took for granted as like, this is part of the process.” Her star-making role in Léon also had a profound impact on the way she approached future filmic endeavours. “There was definitely a period where I was reluctant to do any kind of kissing scenes, sexual scenes. Because [for] my first roles, the reaction people would [give] in reviews [was to] call me a ‘Lolita’ and things like that, and I got so scared by it,” she said. “And I think that’s also got to be part of our conversation now: when you’re defensive as a woman against being looked at that way, that you’re like, ‘I don’t want to’ — what do we close off of ourselves or diminish in ourselves because we want to protect ourselves?”

It’s hard not to feel icky watching certain scenes from Leon’s extended cut, but in an era of cancel culture gone mad, that shouldn’t be the extent of our relationship with the film. Besson’s private life notwithstanding, Leon: The Professional, particularly in the absence of those pesky superfluities, has aged incredibly well. The story may pose uncomfortable questions, but these are deeply dysfunctional characters in uniquely desperate circumstances, and the film’s central relationship maintains an endearing sweetness that speaks more to paternal instincts. Then there’s Portman herself, a mindboggling talent who wowed a generation with an impossibly complex turn for someone so young. Reno’s character may adorn the marquee, but this is Portman’s movie. Fearlessness has rarely been so captivating.

Director: Luc Besson

Screenplay: Luc Besson

Cinematography: Thierry Arbogast

Music: Éric Serra

Editing: Sylvie Landra