Tony Scott’s Tarantino-penned pop culture fantasy still rocks three decades later

The fact that Quentin Tarantino honed his craft while working as a VHS rental clerk has long been a part of Hollywood lore. That a movie-obsessed geek managed to transform himself from a minimum wage lackey into the medium’s newest prodigy, all in less than a decade, is such a romantic notion — the kind of unlikely success story that you don’t see too often. Variations of that story, some suggesting that Tarantino’s tenure at Video Archives in Manhattan Beach, California, transformed him into the veritable encyclopaedia of film knowledge that we know today, are a little wide of the mark (he was actually hired back in 1985 because of that knowledge), but seven years watching in-store movies certainly broadened his horizons, allowing him the time and experience to dream-up some of the most iconic movies of the late 20th century.

So profound was Tarantino’s influence on the mainstream during the early 90s that he seemed to come out of nowhere, but he was already something of a celebrity on the fringes of Tinsel Town. “Me and the other guys would walk into the local movie theater and we’d be heading toward our seats and we’d hear, “There go the guys from Video Archives,” Tarantino would recall. “We were known all over that town. In a strange way, Video Archives in Manhattan Beach was a primer to what it would be like to be famous. Everyone in Manhattan Beach knew who I was. I couldn’t walk down the street without people calling, “Hey, Quentin. Hey, Quentin!”

It wasn’t long before the name Tarantino rang out across the world. His rise to superstardom was monumental, Pulp Fiction becoming the first independent film to gross more than $200,000,000. The movie would also land Tarantino and co-writer Roger Avery, who QT had first met at Video Archives, a shared Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay, but it didn’t happen overnight. Though his first film, a 1987 short titled ‘My Best Friend’s Wedding’, was accidentally destroyed, Tarantino continued to attend acting class, eventually pursuing writing and directing. His first paid writing gig was for cult genre-mash From Dusk Til Dawn, a movie that wouldn’t get made for another half-decade. By then he had already written and directed City of Fire derivative Reservoir Dogs, an all-star crime caper that introduced Western audiences to the filmmaker’s innovative use of music and unique writing style, presenting us with characters who would shoot the shit like regular folk rather than existing as expositional devices to move the plot forward. Though the film bombed at the box office, it would become an instant cult classic on the home video market. The era of Tarantino was well and truly underway.

Tarantino’s first involvement in a major studio picture was actually sandwiched between Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction. The script for 1993’s True Romance, a movie that the filmmaker was originally set to direct, was instead sold for $50,000 in the early 90s, money that was used to fund Reservoir Dogs. Described by Tarantino as his “most autobiographical” screenplay, the movie certainly seems to be a reflection of his time working at Video Archives, which closed its doors less than a year after the release of True Romance. I’m not suggesting that he fled the scene of a murder with a million dollars worth of yeyo in-between shifts, but he surely fantasised about such scenarios. You can imagine him pepped-up on coffee, furiously scribbling down notes as customers lingered on the cusp of a rental that might never happen.

It’s nice to meet people with common interests, ain’t it? Well, enough about the King, how ’bout you?

Clarence Worley

Incredibly, Tarantino’s extraordinary career almost didn’t happen. The future filmmaker was so satisfied with his role of video store celebrity that he kind of lost focus for a while, almost buying the ultimately doomed business. “I found Video Archives in Manhattan Beach and I thought it was the coolest place I had ever seen in my life,” Tarantino would explain. “The owner asked if I wanted to have a job there. He didn’t realize he was saving my life. And for three years, it was really great. The case could be made that it was really too terrific. I lost all my ambition for the first three years. I stopped trying to act and trying to direct... At a certain point I got to know everyone’s taste. And after three years, it got to be a real drag putting movies in people’s hands. When I started getting sick of the place, I started to reconnect with my ambition... At one point, I brought all of the employees together to talk with them about an employee takeover. Now, none of us had any money, but this was a legitimate business thing. “Go to your parents and borrow the six thousand dollars, you and you and you and you. This is all legit.” Nobody was interested. I loved the place. I was really, really invested in it. The truth of the matter is, if we had done that, I may not have made Reservoir Dogs. I would have been working at, and owning, Video Archives.

They say write about what you know, and even before Tarantino’s autobiographical admission, it was obvious that protagonist Clarence, one half of the film’s Bonnie and Clyde, is a thinly-veiled variation of the real-life, pre-Hollywood Tarantino, one plunged into a pop culture fantasy with so many music and movie references that recognising them becomes a joy in itself. Clarence Worley is an enigmatic comic store clerk and Elvis Presley obsessive with a fetish for kung-fu movies, a Gen Xer with a social imbalance that has left him one milkshake away from all-out rampage. His actions are even determined by visions of ‘The King’ himself (a faceless Val Kilmer in one of a plethora of priceless cameos).

The movie begins with Clarence making small talk with a loose woman in a dingy bar. The topic of conversation is fucking Elvis, an early signifier of the character’s detachment from reality. Clarence is edgy, living on the fringes, but also queerly charismatic. When he asks the woman if she’d like to go to the movies, she’s vaguely interested, but when he suggests that they see a Sonny Chiba triple bill, she realises something’s not quite right. Such myopic behaviour has left Clarence somewhat alienated, but it also makes him unique and compelling. Based on his work and various interviews, you have to believe that a young Tarantino was those things too.

The title and plot of True Romance are based on the romance comic books of the mid 20th century, which typically played on themes of jealousy, betrayal and heartache, with a wildly overblown pulp charm that erred towards the overly dramatic. Similarly, True Romance has little to do with reality. The characters have no real substance, the events hold no real emotional consequence, but that’s precisely the point. Instead, we are treated to a whirlwind of frenetic action and dead-on comedic flourishes, scenes emboldened by a colourful cast of characters, some of whom border on straight-up parody at times. A couple of hyper-tense set-pieces, frenetically captured and tinged with moments of gorgeous flamboyance (like the flurry of feathers that decorates the film’s bloodthirsty shootout), smack of Tarantino at his most breathless, the screenplay weaving narratives like a silk spider dipped in testosterone.

The man responsible for bringing True Romance to the screen, the late action movie dynamo Tony Scott, is certainly the man for the job, delivering what many consider to be his finest film. Most synonymous with high-octane action vehicles such as Top Gun and Beverly Hills Cop 2, the distinctly mainstream Scott and the always unconventional Tarantino may seem like an ill fit, but the film’s shallow, full throttle antiheroes are a perfect match for Scott’s frenetic, hyperbolic approach, which lends the screenplay a raw urgency befitting of the bloody, breathless adventure that assaults us from the off.

Please shut up! I’m trying to come clean, okay? I’ve been a call-girl for exactly four days and you’re my third customer. I want you to know that I’m not damaged goods. I’m not what they call Florida white trash. I’m a good person and when it comes to relationships, I’m one-hundred percent, I’m one hundred percent… monogamous.

Alabama Worley

True Romance also benefits from a quite incredible cast, something Tarantino has been blessed with from the very beginning ― a testament to his incredible talent and transformative influence. The filmmaker revolutionised screenwriting to such an extent that everyone wanted in on the act, some of the industry’s biggest stars queuing to catch a ride on the Tarantino freight train. His films made such an immediate impact that the days of contrived screenplays with perfunctory dialogue were as dead as a headless gangster buried deep in the Nevada desert. What followed was a slew of Tarantino imitators, films like Killing Zoe, Things to Do in Denver When You’re Dead and U Turn all aping Tarantino’s all-encompassing style to varying degrees of success. Today, those films smack of a very distinct period in film history, a time when the gangster genre underwent wholesale changes. Tarantino forged that period, but unlike the work of many of his spellbound contemporaries, his movies survived it.

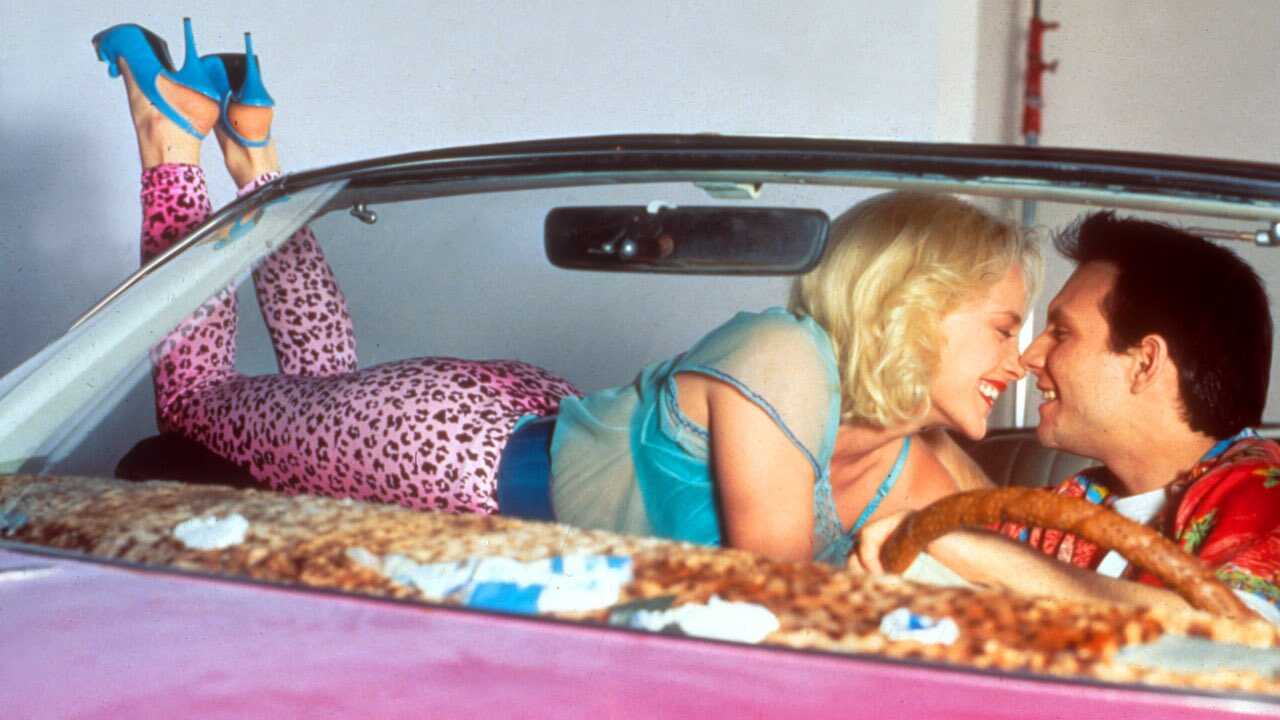

Like Tarantino, Clarence lives in his own world, is governed by his own rules. That world suddenly becomes a whole lot bigger when naïve call girl Alabama is paid to stumble into his life. Clarence and Alabama’s romance is fast and fickle, sweet and unconventional. It is fast food love, not the kind of relationship you can buy into on any serious emotional level. One minute Alabama in spilling popcorn on her unsuspecting client’s lap, the next they’re married and getting his and hers tattoos in a sleazy LA parlour. Both characters are clearly unstable, but so is the movie. In reality, a couple like this would be at each others’ throats and divorced in a heartbeat, but True Romance has no time for substance. Its intentions, like their relationship, skid on the fringes of fantasy like a leopard print Cadillac on some far-out highway, a fact beautifully punctuated by Hans Zimmer’s dreamy, ethereal theme ‘You’re So Cool’, a pan flute love letter to modern day rebellion that smartly juxtaposes with the film’s violent indulgences. Clarence and Alabama’s love is flighty yet fiercely loyal. You just know there’s no one else in the world for either of them.

Though Clarence is the film’s obvious antihero, it is Patricia Arquette’s Alabama who shines brightest. Alabama is a part of QT’s legendary shared universe, a call girl previously mentioned by Mr. White in Reservoir Dogs who was certainly worth further exploration. Here she works on raw emotion, possessed by a carefree nature that belies her oppressed corner of the world. Clarence is the wild card, but Alabama has heart in abundance, a fact confirmed during an excruciating scene with the late James Gandolfini, whose emotionally corrupt gangster, an early audition for the role that would one day define him, beats her to a pulp before succumbing to her tenacious will for survival. The scene in question was criticised for its extreme violence, particularly the image of Arquette’s bloodsoaked breasts as she bludgeons her aggressor to death and beyond, a moment which irked the MPAA no end, but more shocking is the scene’s graphic depiction of violence against women. In the end, Alabama gives as good as she gets.

Tarantino has often been criticised for his weak depictions of women, most recently his handling of complex Manson Family victim Sharon Tate. Some critics suggested that Tarantino’s Once Upon A Time In Hollywood objectified Tate, his decision to focus on Leonardo DiCaprio’s washed-up actor Rick Dalton and Brad Pitt’s insouciant stunt man Cliff Booth at the expense of a prominently billed Margot Robbie considered something of a cop-out, but when has Tarantino ever explored complex characters in realistic ways? Typically, Once Upon A Time In Hollywood defies expectation, giving us a revisionist history full of fictional faces. Like True Romance, it embraces violence unashamedly, creating a fantasy world full of fanciful characters. Alabama has very little depth, same as every character in True Romance, and traditionally speaking this is very much a male-oriented movie, but her paper-thin idiosyncrasies make her the film’s most endearing character. She’s right out of the pages of one of Clarence’s comic books.

Our fated couple’s post-date adventure begins in a seedy whorehouse in the ass-end of nowhere. When Clarence discovers that Alabama is indebted to a callous, drug-dealing pimp named Drexl, his first instinct is to pay him off, only the envelope he hands him is empty, our first glimpse at Clarence’s erratic, take no prisoners attitude. As Drexl so eloquently puts it, he’s dealing with a “motherfuckin’ Charlie Bronson”, a kid who’s seen one too many movies. Drexl’s involvement, like that of the majority of the film’s characters, is fleeting but unforgettable, especially since he is played by an almost unrecognisable Gary Oldman in one of the most incredible, against type transformations I have personally ever witnessed. Heavily scarred, armed to the gold teeth with gangster patois and sneering from behind one milky eye, Oldman, who is notoriously picky about his roles, is a revelation as Drexl, hamming it up to glorious levels as the delusional white guy drenched in black culture. During an incredibly tense and bloodthirsty standoff, Clarence manages to get the better of his dreadlocked foe, and when he accidentally leaves with a million dollars worth of uncut cocaine, his reckless pursuit seems to have paid off.

Marty. Y’know what we got here? Motherfuckin’ Charlie Bronson. Mr. Majestyk.

Drexl Spivey

Problem is, Clarence leaves his ID card at the scene of the crime, Drexl happens to be associated with a notorious mafioso named ‘Blue’ Lou Boyle, and when Boyle’s goons catch up with Clarence’s father Clifford (Dennis Hopper), the shit really hits the fan. The scene in question, the most engaging in the entire movie, involves a tense stand-off between Hopper’s retired cop and Christopher Walken’s serpent-eyed mobster Vincenzo Coccotti, who offers to spare his life in exchange for the whereabouts of his son. Tarantino has also been widely criticised for his heavy-handed use of racial slurs over the years, and this scene really piles it on, suggesting that Sicilians were “spawned by niggers”. All these years later, it’s a little on the nose, but the scene is still utterly compelling. The history may be inaccurate, the sentiment may be nauseating, but it is relevant to the material and its characters. Ultimately, we’re treated to two world class actors revelling in the revolutionary style of a true innovator.

True Romance isn’t so much character-driven as it is actor-driven. The characters are indelible, even those who pop in for little more than a cameo, but it is more an ensemble of talent delivering quick and memorable turns, each relishing in the chance to take part in Tarantino’s colourful universe. There is such a wealth of talent on display that it almost feels meta at times. Even those on the periphery who would be relegated to extra status in lesser movies are memorable in some way. Thirty years later, many of them are established faces in their own right. The film has such pedigree.

But for all the action and intense set-pieces, the movie’s biggest strength is its sense of comedy. True Romance is so much fun for everyone involved. Tarantino and Scott take particular delight in satirising Hollywood. A prime example comes courtesy of Saul Rubinek’s coke-addled movie director Lee Donowitz, an acid-tongued windbag looking to score Clarence’s million-dollar haul for a fifth of the price. Donowitz was purportedly created as a thinly-veiled dig at producer Joel Silver in response to the toxic production of Scott’s previous movie The Last Boy Scout, though Rubinek, an actor renown for his improvisational skills, created him as an amalgamation of Hollywood types.

In a 2015 interview with KPCS, Rubinek would cite an unnamed executive as the inspiration for one of the character’s most priceless lines. “No [the line ‘I’ll have you fucking killed’ was not in the script],” he would explain. “There was an article about a studio executive talking to a writer, saying ‘I will have you fucking killed. I have people on the street; I’ll have you fucking killed… it wasn’t Joel Silver. Joel Silver’s a producer, not a studio executive. This was a studio executive; a very famous one, whose name’s gone out of my head… But he told a writer, ‘What do you mean? I have people on the street. I’ll have you fucking killed. I couldn’t believe that line. And a car cut me off while we were shooting in Malibu and I just improvised and said ‘Don’t give me the finger; I’ll have you fucking killed.’ Tony let us improvise a lot.”

Playing the Smithers to Donowitz’s Burns is the delightfully obsequious Elliot Blitzer (Bronson Pinchot in irresistible form), an industry toady who gets caught in the film’s increasingly entangled plot threads like a spineless insect in a particularly sticky web. Blitzer becomes the bitch of the equation after a self-serving date slaps him in the face with a half-pound of cocaine in plain sight of a traffic officer. When he winds up in the clutches of a pair of ambitious detectives (Chris Penn and Tom Sizemore), Blitzer is forced to wear a wire and enter the lion’s den while setting up the coke deal, resulting in an excruciating stand-off involving the cops, Clarence and his ragtag crew, a pair of arrogant bodyguards and a gang of mafioso. Pinchot has a habit of stealing the show (his priceless turn as effeminate art dealer Serge in Beverly Hill’s Cop leaps to mind), and his portrayal of just how low a person will sink to make it in ‘La La Land’ is one of the film’s many highlights.

Huh? You want me to suck his dick?

Elliot Blitzer

Tarantino and Scott’s satirising of Hollywood goes way beyond petty beefs with real-life figures. Everywhere you look ‘Tinsel Town’ is the subject of some serious lampooning. There’s the brief, yet hilarious scene in which Conchata Ferrell’s hyper-cynical casting agent auditions Michael Rapaport’s hopeless rookie and long-time Clarence buddy Dick Ritchie — for a supporting role in William Shatner’s TJ Hooker no less. The cocaine is dubbed Dr Zhivago. Elliot is forced to ‘get into character’ to pull off his insidious part in proceedings, hinting that he may even be willing to suck Clarence’s dick for the sake of his career. Even a young mafioso, popping his cherry with his first potential shoot-out, does his best Robert De Niro impression as he gears up for the big day, much to the amusement of his wise guy brethren. There’s also a priceless turn from a young Brad Pitt as a flaked-out stoner who spends his days drinking beer and watching cult B-movies in Dick’s apartment, so wasted that he offers his bong to a gang of heavily-armed goons as they press him for information. The entire movie is a cute ode to the crazy world of modern Hollywood and the movies and personalities that it produces.

Despite the blood and the bodies and its wicked sense of irony, True Romance is that rare 90s gangster film that features a happy ending, at least for those who matter most to us. By the early 90s, tragic endings were almost a given. Society was changing, audiences were beginning to root for the antihero, and dark endings were the in-thing. True Romance teases tragedy in a way that maintains the movie’s cool, but ultimately the film lives up to its alternative fairy tale aspirations. Tarantino’s original screenplay actually featured a more tragic conclusion that ended with Clarence dying and Alabama escaping alone with the money, solidifying her status as the film’s true protagonist. The alternate ending was filmed but ultimately nixed by Scott, who insisted that it was his decision and not the studio’s as some would suggest. “I just fell in love with these two characters and didn’t want to see them die,” Scott revealed. “I wanted them together.” Surprisingly, Tarantino approved of Scott’s decision to alter his original vision, admitting, “When I watched the movie, I realised that Tony was right. He always saw it as a fairy tale love story, and in that capacity it works magnificently.”

That’s the beauty of True Romance. Though it is very much a Tarantino film, it is just as imbued with Scott’s hyperbolic action style, a winning matrimony of two of Hollywood’s strongest personalities. Unlike Scott’s previous film, there are no egos spoiling the collaborative broth. What we get is a mindboggling ensemble of some of the industry’s finest talent all coming together in perfect harmony, forging one of the freshest, wittiest crime thrillers of the era. Thirty years on, True Romance continues to stand tall amid a creative bonfire of Tarantino derivatives that failed to pass the test of time. It (very consciously) lacks emotional depth and realism, but its modern cult status is more than deserved.

During the films’s bravura climax in the ill-fated confines of a decadent hotel suite, Clarence, again speaking for Tarantino, condemns the ball-less nature of the Academy Awards. “Lee, most these movies that win all the Oscars I can’t stand. They’re all safe, geriatric, coffee table dog shit…” he tells a manic, coke hungry Donowitz. “All those assholes make are unwatchable movies from unreadable books. Mad Max, that’s a movie. The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, that’s a movie. Rio Bravo, that’s a movie.” With its fast food thrills, endlessly quotable dialogue, and a myriad of colourful performances from some of the industries most iconic stars, True Romance is a movie in the purest sense.

Director: Tony Scott

Screenplay: Quentin Tarantino

Music: Hans Zimmer

Cinematography: Jeffrey L. Kimball

Editing: Michael Tronick &

Christian Wagner