Bill Murray waxes cynical in Harold Ramis’ irresistible time loop comedy

Okay, campers, rise and shine! And don’t forget your booties because it’s cold out there today! It’s cold out there every day. That’s right woodchuck chuckers, it’s… GROUNDHOG DAY!

One of the drawbacks for a writer publishing an article with an annual festivity in mind is the prospect of immediate irrelevance. It may grab your attention on a specific day, but there’s a very small window before that article becomes obsolete (at least until the following year). But what if we were to relive that day over and over, would that article continue to be read day after day? And even if it was, would it be of any worth to anyone? If we were stuck in a constant time loop, what use would that information be going forward? Whatever the consumer has learned is only temporary, and even if, in that temporary state, they were able to pass on information that might be of great use to someone, what good would it do them if they were back to square one the very next day?

Today, Tuesday, February 2, is a day that many of you had likely never heard of until it was immortalised by Harold Ramis’ truly inspired meta comedy Groundhog Day, a film whose concept has experienced something of a resurgence in recent years. 2011’s sci-fi conundrum Source Code, 2017’s gloriously playful slasher Happy Death Day and 2020’s almost like-for-like gallows humour comedy Palm Springs all reworked the concept for modern audiences, which only highlights its versatility and timeless appeal. In fact, it’s amazing to think that such a novel creative hook didn’t rise to mainstream prominence much earlier.

It may or may not surprise you to learn that the concept was already out there, it just needed tweaking. When I first saw the likes of Happy Death Day, I immediately called out “Groundhog Day!” like an erroneous, small-town disc jockey incessantly bleating from an alarm clock radio. Though pretty much everything has its influences rooted somewhere, it never crossed my mind to question Groundhog Day‘s integrity, and why should it? It’s such a pitch-perfect film. Even if Ramis and co did steal the idea as was later claimed, they did such an immaculate job, both creatively and commercially, that it was bound to become the standard bearer. Anything short of a truly great movie from the accuser would have left them playing catch-up regardless of timeline.

That’s not to say previous incarnations weren’t noteworthy. Groundhog Day is actually based on Richard Lupoff’s 1973 short story 12:01 P.M., the tale of a New York executive living the same hour over and over that was actually made into a TV movie the same year that Groundhog Day was released, something that almost led to a legal battle.

As Lupoff would recall, “A brilliant young filmmaker named Jonathan Heap made a superb 30-minute version of my short story 12:01 PM. It was an Oscar nominee in 1990, and was later adapted (very loosely) into a two-hour Fox movie called 12:01. The story was also adapted — actually plagiarized — into a major theatrical film in 1993. Jonathan Heap and I were outraged and tried very hard to go after the rascals who had robbed us, but alas, the Hollywood establishment closed ranks. We were no Art Buchwald. After half a year of lawyers’ conferences and emotional stress, we agreed to put the matter behind us and get on with our lives.” Interestingly, Lupoff would star as an extra in both movies.

What would you do if you were stuck in the same place. And everything was exactly the same. And nothing you did mattered?

Phil

Lupoff and Heap weren’t the only ones to cry foul. On Decemeber 7, 1995, the case of Leon ARDEN, Plaintiff, v. COLUMBIA PICTURES INDUSTRIES, INC., Danny Rubin, Harold Ramis, and Trevor Albert, Defendants, transpired at the United States District Court, S.D. New York. Arden had published the novel One Hard Day in 1981, the story of a man forced to repeat the same day over and over which he declared had also been plagiarised by Ramis and his associates. The author’s claims that the plot, mood, characters, pace, setting, and sequence of events had all been lifted from his work were overruled, as no reasonable jury could find that the two works were substantially similar within the meaning of the Copyright Act, the Lanham Act and principles of common law.

While One Hard Day was described as ‘dark and introspective, featuring witchcraft and an encounter with God’ and involving recurring air disasters, the rape of a young woman and the suicide of another, Groundhog Day was ‘essentially a romantic comedy about an arrogant, self-centred man who evolves into a sensitive, caring person who, for example, in his repeating day, saves a boy falling out of a tree, changes a flat tire for several elderly women, and learns to play the piano.’ Ultimately, the jury ruled in favour of the defendant because any similarities found related only to ‘unprotectible ideas, concepts, or abstractions.’ Though I’m sure Columbia’s team of high-priced lawyers had some kind of bearing on proceedings.

Groundhog Day may have borrowed one of the most intriguing concepts in the history of cinema, but it most certainly popularised it, the movie grossing $70,900,000 in North America. It also fine-tuned it to truly exceptional levels. The fact that Ramis and co manage to tread a deeply cynical path while delivering the kind of heart-warming mainstream parable that almost always descend into mawkish idealism is an incredible feat, one that qualifies Groundhog Day as not only one of the finest comedies of its era, but one of the most hilarious and fulfilling ever committed to celluloid. With the sheer abundance of second-rate romcoms flooding streaming platforms across the globe, many of them scarred by excruciating sentimentality, it’s still as refreshing and remarkable as ever.

Central to that is the casting of Bill Murray in what, for me, remains his greatest ever comedic role. It’s the actor’s unrivalled ability to portray deeply cynical characters while still erring, often tenuously, on the side of endearment, that makes him such a unique and rewarding talent. Murray’s character, Phil Connors, is a pure bastard, a self-centred curmudgeon who acts like a God among peasants, passively mocking his position as a small-time weather reporter as he awaits brighter pastures that will likely never appear. Phil treats his colleagues as mere stepping stones on his path to nationwide fame, but he’s become complacent in his never-ending routine, his weather reports so dry you can practically taste the derision.

The worst part of Phil’s job is his annual trip to the snow-covered Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania, a simple town of simple pleasures that may as well be purgatory to a cynic like Phil, a notion that soon becomes literal. Everything is slow in Punxsutawney, people are polite and good-mannered. When Phil awakens during what should be a one-off stay at a local hotel, he shoots down a friendly greeter and bamboozles a mild-mannered lady with an ironic torrent of weather information when she was merely making chit-chat. The moment reminds me of a typically scathing Oscar Wilde quote, “Conversation about the weather is the last refuge of the unimaginative.” You get the impression that Phil feels that way too — about his own profession no less — but Wilde has nothing on Connors for sheer acidity. The fact that Mrs. Lancaster, who later mistakes déjà vu for something that might be available in the kitchen, is too naïve to realise she’s being insulted, only seems to draw Phil further into his spiritual black hole.

I didn’t JUST survive a wreck. I wasn’t just blown-up yesterday. I’ve been stabbed, shot, poisoned, frozen, hung, electrocuted and burned. And every morning I wake up without a scratch on me, without a dent in the fender. I am an immortal.

Phil

The thing that really sticks in Phil’s craw is the whole concept of Groundhog Day. ‘Punxsutawney Phil’ (yes, Murray’s character and the groundhog share the same name, something a pair of slack-jawed gawkers are only too happy to point out) is treated like a celebrity in the postcard town of Punxsutawney, something else that seems to irk the egocentric star. That’s because superstition, described as “a belief or practice resulting from ignorance, fear of the unknown, trust in magic or chance”, has bequeathed an otherwise docile and passive creature an incredible, wholly fictitious ability: the ability to predict the end or continuation of winter. Phil resents the town’s quaint traditions and those who buy into them, partially because he feels they’re beneath him, but mostly, one suspects, because they represent communal togetherness, something a selfish, self-serving pig like Phil doesn’t understand. Yet…

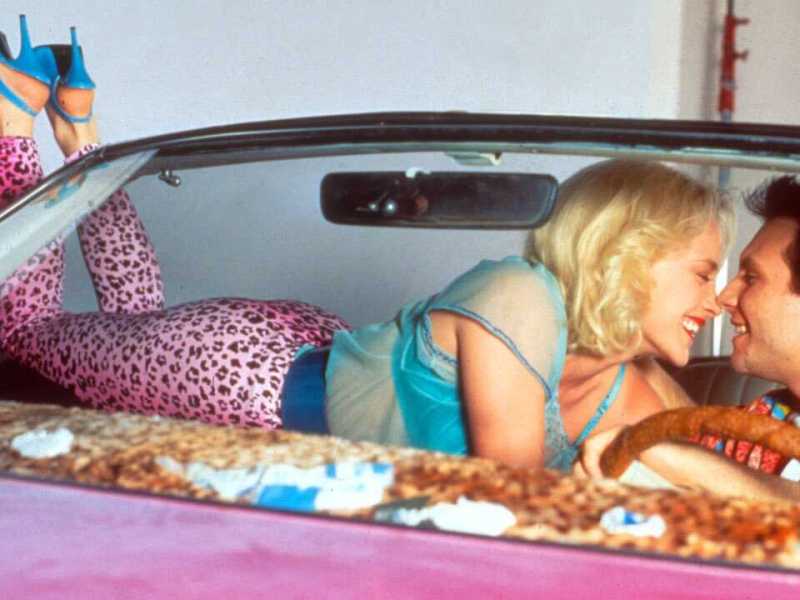

Phil’s salvation comes in the form of a caring, hopeful woman, though his initial intentions are less than noble. Andie MacDowell’s Rita Hanson is a station producer who’s the complete antithesis of Phil, a person who enjoys the finer things, craves world peace and prefers to ‘go with the flow’ rather than chase a hotshot career at everyone else’s expense. She’s kind, thoughtful, patient, and mostly accepting of Phil’s odious ways; your typical romcom sweetheart in just about every way imaginable. In fact, Groundhog Day is very much a typical romcom in terms of execution. If it wasn’t for Murray’s casting, the film probably would have descended into generic, saccharine territory rather quickly. Tom Hanks was actually Ramis’ first choice for the role, but turned it down, rationalising that the film’s redemptive qualities would be too predictable with him in the lead. With instincts like that, it’s no wonder he’s enjoyed such a long and diverse acting career.

Chevy Chase and Michael Keaton, actors who were probably more suited than Hanks, were also considered, as was Kevin Kline, who had won a Best Supporting Actor Oscar for his inspired comedic turn as deadly assassin Otto in the glorious Python-led romp A Fish Called Wanda, but Ramis understood Murray’s talents and potential suitability for the role, even if others feared that he lacked the acting credentials. The two had already starred in an incredible five movies together, comedy classics such as Meatballs, Caddyshack, Stripes and Ghostbusters I & II all cult favourites in their own right. The two had improvised together from the very beginning, having met at Chicago’s Second City, the infamous improvisational sketch comedy troupe that would lead the two to Hollywood superstardom by way of Saturday Night Live, and Groundhog Day, a film as befitting of Murray’s unique persona as any I care to imagine, is an incredible achievement, an inspired matrimony that remains a high point for the two in collaborative terms.

Unfortunately, Groundhog Day would also bring an end to the pair’s longstanding relationship. Tensions began over their differing views of what the screenplay should emphasise. Writer Danny Rubin had consciously tailored the script to Murray’s strengths, but Murray, whose desire it was to be taken more seriously as an actor, wanted the script to focus more on the film’s philosophical capacities. Ramis, however, preferred to focus on the redemptive power of love, which as Murray would later admit, was the right choice both creatively and commercially. Tensions grew onset, partially due to personal issues on Murray’s part. Murray would turn up to the set late and refused to interact with or just straight-up ignored Ramis for the most part, Rubin forced to become an intermediary as production walked a prickly path, and the tensions didn’t end there. The two would become estranged for more than twenty years following their time together on Groundhog Day, Murray finally convinced to visit his dying friend just prior to his passing on February 24, 2014, though what they spoke of remains between them.

Well you can [plan the perfect day]. It just takes an awful lot of work.

Phil

One of the most satisfying elements for an audience is participation. It’s so much fun being in the know and watching characters stumble upon the same realisation after the fact, allowing us to pre-empt their every move. In a horror movie, it might be the knowledge that a seemingly dead monster is stirring in the background (think Laurie Strode and Michael Myers in Halloween). In a murder mystery, we may identify something that reveals the killer to us before the protagonist, now in a potentially fatal situation, is even aware. Groundhog Day takes that sense of participation to the next level, adding a meta flourish that further liberates the film from typical romcom complacency. It’s almost as if we’re re-drafting the script in real-time as we search for the correct way to achieve a desired outcome, but the more we tweak it the more flawed our pursuit becomes. The more we push for convention the more it slaps us in the face.

It’s a rare romantic comedy that steers clear of emotional manipulation, but it’s an even rarer one that reveals manipulation as its trump card. Snowed-in by an unexpected blizzard, Phil and his crew are forced to stay one more night in Punxsutawney, his time loop becoming a cruel magnification of all his worst fears. If he thought his professional life was hopeless within the confines of a linear timeframe, what chance does he have for personal advancement when robbed of tomorrow, stuck in a town that is the complete antithesis of a post-modern world? Phil can’t even take solace in the fact that he’s reliving a good day over and over. He’s awoken at 6am sharp by Sonny and f*cking Cher, the words ‘I’ve Got You, Babe’ an immediate reminder of his lonely, futile predicament. It’s freezing outside, his hotel has no hot water, a homeless man has the gall to ask for some spare change. He even runs into an old high school friend that he has absolutely no recollection of. And not just any high school friend, but Ned Ryerson, aka ‘Needlenose Ned’ aka ‘Ned the Head’, a generic insurance salesmen who proves the personification of all his pet peeves. Phil even has the misfortune of stepping in a particularly deep and icy puddle, a real “doozy” that triggers Ned’s odious heckling. When Phil eventually lays him out cold with a punch, it feels justified — an incredible feat given our protagonist’s haughty disposition. In a film full of memorable minor characters, Stephen Tobolowsky’s Ned stands tallest, those early set-up scenes some of the most memorable.

If Phil’s thinly-veiled sense of detachment has become somewhat complacent in everyday life, the immediacy and finite nature of his predicament only augments his thoughts and feelings. A few initial instances of anarchy aside, it does so in typically unflinching fashion, tussles with dismay, self-destruction and ultimately suicide coming to the fore like trapped wind escaping in a melancholy belch. Believing himself to be an immortal who is unbound from consequence, Phil scarfs down cream cakes, indulges in death-defying joy rides and even careens off a cliff with the cursed groundhog in tow. When multiple suicides fail to relieve him of his reciprocal nightmare, he comes to the egocentric conclusion that he is god. Not THE God, but A god. At least, he doesn’t think he’s THE God. Though he’s living proof that stranger things have happened.

Whatever happens tomorrow, or for the rest of my life, I’m happy now… because I love you.

Phil

With such power comes omnipotence, and if Phil is to be stuck in this less-than-idealistic hellhole indefinitely, he figures he may as well act the devil. Phil sets about using his predicament to his advantage, seeking information and analysing the day’s situations as he plots robberies and beds the local skirt, manufacturing fictitious histories and doing everything in his power to fulfil every sordid whim. Ultimately, it’s a bottomless pursuit, particularly when the thing that he really desires seems beyond even the most studiously plotted narrative. Scenes in which Phil attempts to execute the perfect day are some of the most hilarious and excruciating that the genre has to offer. Phil lies, imitates, flatters, giving Rita everything she wants in life, but true love is never so straight forward, and, crucially, Rita isn’t the kind of girl who will jump into bed with someone on the first night.

It’s after Phil convinces Rita of his meta predicament, only to awaken alone in bed the following morning, that a true miracle happens: Phil begins to put others first. Instead of treating people like cattle, he focuses on the needs of the individual, and, through the unalterable cycle of a dying old man, begins to understand that some things are beyond our control. He also becomes the very things that Rita wants in life — not through an insidious need to impress and exploit, but because he truly wants to, because he feels that it’s what she deserves. The continuous routine that he has mocked, shunned and gone out of his way to hide from he now embraces wholeheartedly. He even delivers an impassioned, on-air speech about the groundhog, igniting the spirits of TV’s routine denizens. In the ultimate irony, Phil spends so much time attempting to deceive Rita that he actually falls head over heels in love with her… like, for real. After being born again over and over… and over, losing and recycling his sense of self, Phil is able to experience true rebirth, a spiritual awakening that frees him from not only the film’s existential trap, but the emotional trap of his own doing.

Beneath the caustic blows and withering bon mots, there’s a spiritual element to Groundhog Day that’s so relatable to late-20th century life and beyond. It has the same redemptive qualities as films such as Michael Powell’s 1946 fantasy-romance A Matter of Life and Death or A Christmas Carol, the latter of which Murray helped to update for the Reagan 80s, starring as cynical television executive Frank Cross in Richard Donner’s yuletide parable Scrooged. Groundhog Day came on the heels of the 80s, a decade of cutthroat self-advancement and free market politics, a time when appearance, fame and wealth were all that mattered. In some ways, Phil seems like a residue of that era, one who missed out on true fame and fortune and continues to pursue it on autopilot. Like a groundhog he’s dug himself a nest and buried his head, popping up with the odd toothy criticism and lamentation of what should have been. His spiritual winter is cold, grey, and set to last for the rest of his life.

But what’s the point of personal advancement if there’s nobody to share it with? What’s the point of ambition if, as a surprisingly astute local drunk points out, it results in a ‘glass half-empty’ kind of guy? Phil is the ultimate postmodern man: conceited, contemptuous, disenchanted, the product of a global world with no time for small-town sentiments. In a relentless rat race of enforced routine and spiritual unfulfillment, it’s easy to be resentful, to be cynical and judgemental, but sometimes all you have to do to appreciate the beauty of life and those who fill it is to slow down for just a minute, or, in Phil’s case, relive a moment in time over and over, until all that’s left is beauty.

Director: Harold Ramis

Screenplay: Danny Rubin & Harold Ramis

Music: George Fenton

Cinematography: John Bailey

Editing: Pembroke J. Herring

From what Harold Ramis said in the DVD commentary, religious scholars see “Groundhog Day” as having a Buddhist theme, in which Phil Connors spends this film doing things over and over again until he finds his center. I like that actually, and I think Bill Murray’s role in “The Razor’s Edge” remake has a similar journey for the protagonist.

Even if one doesn’t subscribe to any theory on this film or don’t care to analyze the proceeding too much, I feel that “Groundhog Day” can be enjoyed just because it’s very entertaining (I first viewed it at the theater when I was 15, so I thought at the time seeing at the scenarios approached in different ways was great, like the audience was in one this fun-although it was hell for Phil!).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi, Eillio.

I read about the whole Buddhist angle while researching. Christians make a similar claim, suggesting it’s actually about god. Ultimately, it’s about man having the time an space to identify and iron out their flaws, which in such a breakneck global world has become a rare thing indeed. It’s certainly spiritual, but I think the struggle lies with the modern-day system and the post-modern cynicism it creates. It’s difficult to identify one’s true self in a world designed to inhibit such notions.

LikeLiked by 2 people

That’s true Edison, that Phil is afforded an opportunity to perfect himself, to find his true self and reach his potential, but in reality, many of us have lives that are constantly evolving so we don’t have as much time (or the same day over and over again) to perfect ourselves. But hey, a lot of us try!:-).

Things are pretty cynical, and a little too PC & repressive, so I agree with you that that’s a daily struggle for the majority of us.

As the film goes, this is why it works so well, since it can cause one to think, or just sit back and enjoy the madness.

LikeLiked by 1 person