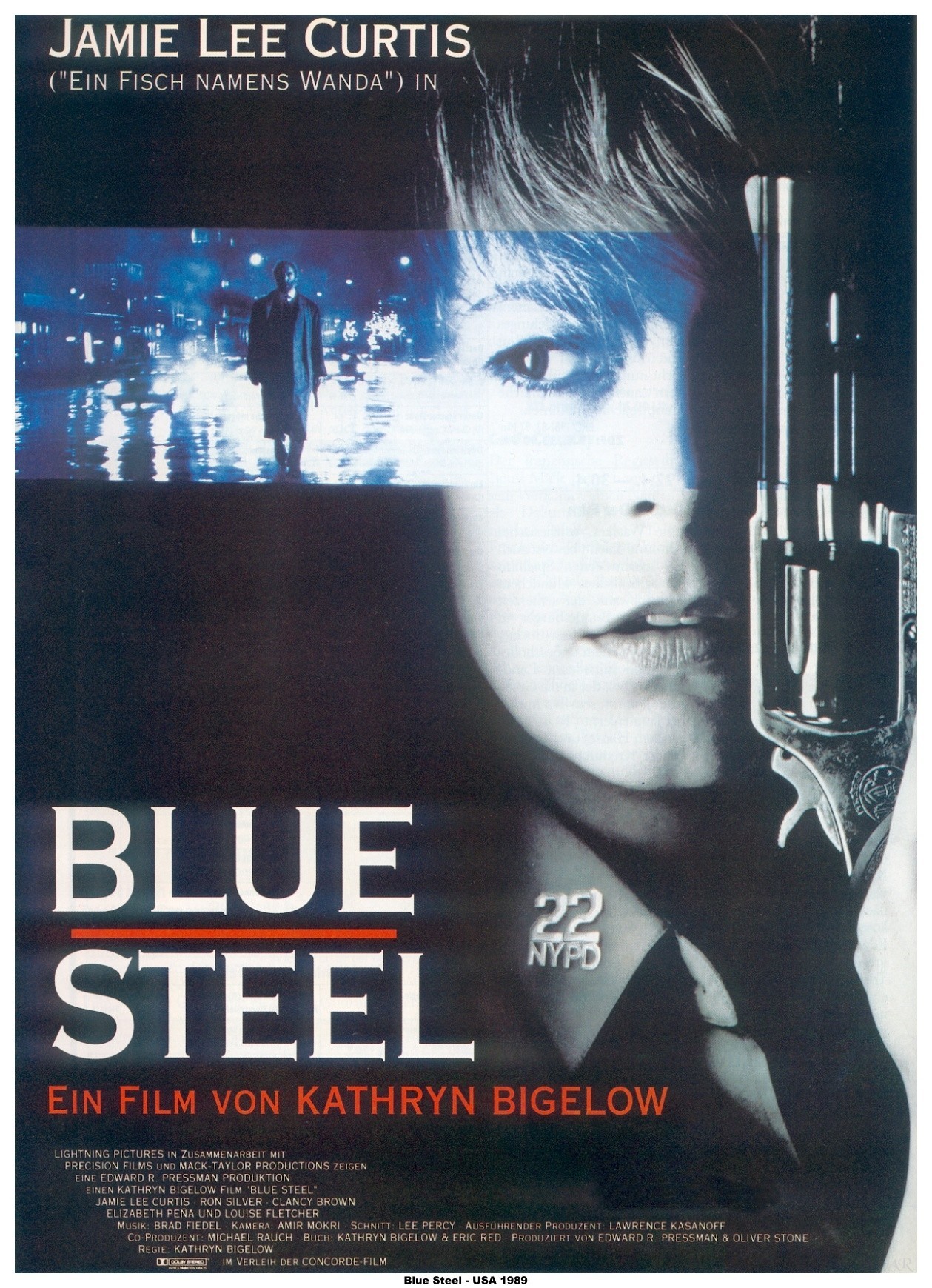

Focusing on the female action hero with Kathryn Bigelow’s quietly influential cop thriller

With Blue Steel, director Kathyrn Bigelow achieves something quite special. In an era of male-dominated action movies she forges a heroine who makes gender arbitrary, who confronts the deep-rooted chauvinism of bureaucracy and challenges the woman’s role in a traditionally male profession, one that portrays her gender as fundamentally helpless. In a working environment where brotherhood ― an expression that is far more literal here than its general sentiment suggests ― is an elemental requirement, Jamie Lee Curtis’ rookie cop doesn’t depend solely on her femininity. Nor does she veer toward the hypermasculine. Her heroism is hard-earned and grounded in personal conflict, the result of a threat she has no choice but to confront. She is scared but never powerless. She defends herself because nobody else can.

The idea that women cannot be trusted in such an environment was and is so deep-rooted that, as a sex, females have largely accepted the role, be that subconsciously or otherwise, and that is certainly the case when we first meet Curtis’ Megan Turner. Turner isn’t your typical oppressed housewife (though the shadow of that particular fate looms large). She’s brave and inspirational with a history of challenging the patriarchal role in the household, a fact that has left her at loggerheads with her very own parents.

Despite a very conscious effort to overcome such a role, the ‘weaker sex’ sentiment is so institutionalised that Turner is left doubting her own gender during a simulated life or death situation in the film’s opening moments, leading to exactly the kind of mistake that her male colleagues, weaned on the philosophy that law enforcement is a strictly male environment with a macho code, would surely pounce upon if it were to happen on the unforgiving and potentially fateful streets. In the scene, Turner is plunged into a tense stand-off with a gun-wielding husband who’s taken his wife hostage in what is her final training exercise prior to graduation. Employing the assertiveness demanded of her, she has no hesitation in blowing the guy away, but when she drops her guard the woman reaches for the gun and blam! Turner has underestimated the other female in the equation. She is guilty of the exact same prejudice.

Traditionally, the woman’s role in action movies is to play the helpless, lovelorn victim and accentuate the alpha male’s heterosexuality. Such characters were still rife in the 1980s, a decade that saw musclebound bodybuilder Arnold Schwarzenegger become the standard bearer for what an action movie protagonist should look like in a society where bigger was better. By the late-1980s, the film industry was awash with beefed-up action heroes. If you reached for an Arnie movie you did so to see him kick some ass and reel-off a plethora of macho zingers. The same can be said for Van Damme, Seagal and a dozen other cartoon heroes with muscles to burn. Women were generally powerless, indebted beauties hanging from those muscles, swooning at the feet of violent retribution. Their only purpose was to lick the tough guy’s wounds and offer up their bodies as some kind of obligation. There’s a McBain sketch in The Simpsons that captures it so perfectly. After breaking up a meeting between international terrorists with a violent display of Alpha male heroics, McBain quips “Meeting adjourned”. By that point a random beauty has appeared as if from nowhere, her only purpose to fawn over his Tarzan prowess. “Right now I’m think of holding another meeting,” McBain adds with that comical Eastern drawl. “In bed!” It’s so crude, yet so accurate. In the realms of 20th century action cinema, women were eye candy, plain and simple.

There were exceptions, characters who would pave the way for 21st century action heroines. With modern society’s continued enlightenment came the emergence of female ass kickers, characters who proved a much more varied bunch. Some, like martial arts expert Cynthia Rothrock, were very much in the alpha male mode, but others had much more depth to their arsenal. Female action stars of this variety began to emerge following the civil rights movement, a time when the woman’s role in fighting for civil liberties became more widespread and widely documented. There were many singular voices prior to the civil rights movement, many groups who were systematically toppled or oppressed, sacrificing more than the kind of self-serving Twitter rants that only serve to cheapen feminism as a concept, but the civil rights period was a huge leap forward in the fight against private power and all that it encompasses, so much that the first female action star was also black.

Pam Grier’s Foxy Brown, a take-no-prisoners smart ass to rival the best of them, may not have been truly mainstream, riding the wave of blaxploitation cinema, but the character broke down many boundaries. Grier had debuted as Coffy a year prior, but it was Foxy Brown, a film seized and confiscated in the UK under section 3 of the Obscene Publications Act, that truly resonated. It wasn’t long before white female action heroes followed Foxy’s lead. By 1979, the female action star had made the leap to mainstream Hollywood, Sigourney Weaver’s Ripley out-surviving the largely male crew of the ill-fated Nostromo in Ridley Scott’s sci-fi masterpiece Alien. As the 90s developed so did female action heroes. In 1991, former Disney cutie and real-life lesbian Jodie Foster would shed convention with her Oscar-winning turn as resourceful FBI agent Clarice Starling, another rookie who would overcome one of cinema’s most fearsome serial killers in Ted Levine’s throaty Jame “Buffalo Bill” Gumb, as well as the devilish mind games of Sir Anthony Hopkins’ evil genius Hannibal Lecter. Challenging Foster for the title of Best Actress at the 64th Academy Awards were Geena Davies and Susan Sarandon, who would cast off the shackles of male dominance as the titular Thelma & Louise, the two bursting their domesticated bubble for a rebellious road trip that smacked of traditional male heroism.

I said put the gun down. Now!

Megan Turner

Perhaps the most relevant character emblematic of such a transition is The Terminator‘s Sarah Connor. In the original movie, Connor is a put-upon waitress with no real goals or ambitions until a fated meeting with Arnold Schwarzenegger’s colossal Cyberdyne Systems Series 800 Terminator alters her destiny irrevocably. Six years later, Arnie would return as a reprogrammed T-800 sent back in time to help Connor and son John, who would one day grow to be the leader of the human resistance. 1991‘s Sarah is a completely different entity: muscular, battle-hardened and aloof to her male captors as a patient in a maximum security psychiatric ward. Rather than fleeing the T-800, this time Sarah becomes his leader. She even exhibits some of the war-hungry irrationality usually reserved for the opposite sex, sneaking off to assassinate a family man who will unwittingly contribute to the end of life on Earth. It’s only fitting that the industry’s most successful action hero plays second fiddle in a narrative sense.

As female action heroes go, Megan Turner is certainly one who gets lost in the shuffle. By 1990, Curtis was much more than horror’s most lauded scream queen. Resourceful heroine Laurie Strode, the long-time nemesis of one Michael Myers, continues to be the role that defines her thanks to one of the most notable horror franchises in history, something that was only strengthened by Blumhouse’s most recent handling of the character. Thanks to a quick succession of ‘final girl’ turns in movies such as The Fog, Prom Night and Terror Train, Curtis was firmly in the annals of horror by the time her career was barely off the ground, but the real-life daughter of Janet Leigh, who would famously become the first onscreen victim of Norman Bates in Alfred Hitchcock’s equally iconic Psycho, had no intention of being pigeonholed and would soon reinvent herself in the realms of comedy, first as spirited call girl Ophelia in John Landis’ Reagan-era re-imagining of the The Prince and the Pauper, Trading Places, and then as duplicitous kink Wanda Gershwitz in A Fish Called Wanda. Curtis put in a prodigious turn as the sassy hellcat tamed by the unconventional allure of British inadequacy, but as ever she was looking to branch out further.

Blue Steel director Kathyrn Bigelow was another female presence who refused to bow to Hollywood convention, though by all accounts this wasn’t a concerted effort, more an organic process of working within a construct and tweaking it accordingly. In 1987, the future Oscar winner would help revolutionise the vampire sub-genre with bloodthirsty neo-western Near Dark, later tackling male-dominated genres with 2002’s historical submarine film K-19: The Widowmaker and war dramas The Hurt Locker (2008) and Zero Dark Thirty (2012). In 1991, she would return to the action genre with cult favourite Point Break, casting a wet behind the ears Keanu Reeves and mainstream heartthrob Patrick Swayze in roles that were deemed unconventional. Point Break isn’t your typical action movie. The tale of an undercover FBI agent and a gang of rogue surfers who double-up as a team of covert bank robbers is a complex scenario where intelligent characters use violence as a means for expressing their political beliefs. The film blurs the lines between good and bad, right and wrong, presenting us with events that belie the genre’s typical macho tropes and black and white delineations.

Blue Steel retains elements of the traditional, male-led action movie and plunges Curtis’ stranger in a strange land slap-bang in the middle. An early fast cut sequence that sees Turner’s rookie cop suited and booted is reminiscent of John Matrix’s lock-and-load Commando motif, Bigelow not shy about using the kind of era-specific, slow motion kills that see villains blasted through plate glass windows in an overblown manner that threatens to keep them in suspended animation forever. Though Turner dabbles in stylised violence, there are consequences to her actions. After foiling a convenience store robbery in a similarly overblown fashion, she is immediately suspended by male superiors who seem unconvinced by their latest female recruit, viewing her as a potentially life-threatening influence on the ‘boys in blue’. Turner’s father is also unimpressed with her career decisions, mainly because he has a history of domestic abuse, something that clearly contributed to her stand against patriarchal dominance. Dad is understandably threatened by Megan’s newfound position of authority, one that broods beneath a manufactured cloud of familial shame.

Turner’s role in the family unit could easily be read as lesbian subtext, her ‘male’ choices seen as a blot on traditional family values. She has a boyish haircut, is frowned upon for her masculine tendencies, and has no qualms about challenging her father’s hypocritical stature as the responsible head of the household. Smartly, Bigelow doesn’t paint the Turner patriarch as nasty or vindictive. He isn’t crucified as an emblem of feminist advancement. He’s simply a human being with human flaws, Megan becoming the mediator and voice of reason. When Turner’s friend attempts to set her up with a male acquaintance named Howard, the man recoils after discovering her chosen profession. Her ‘male’ position leaves him feeling disempowered, his immediate attraction to her dwindling as if it were little more than an illusion, a witch’s spell that had left him temporarily bamboozled. Longstanding rumours that Curtis was born a hermaphrodite, however spurious, also makes her inspired casting for such a role, the actress giving a truly inspired performance.

You’re a good-looking woman; I mean, beautiful, in fact. Why would you want to become a cop?

Howard

Curtis is absolutely the best thing about Blue Steel, the industrial adhesive holding it all together. She’s the immovable object of a film that often feels ethereal, that’s shot with the heady flourishes of an elusive and wildly extravagant nightmare. For a film that so openly challenges the female role in society, Curtis is a hugely likeable presence ― an essential attribute at a time when female action stars were still frowned-upon outsiders for a generation of men weaned on altogether different values. Curtis brings so much range to the Turner character. She’s brave, determined, independent, yet deeply unsure of herself, fragile and ultimately alone. Turner inhabits a profession that has her pegged as an ill-fitting piece in the puzzle, an agitator to the ‘natural order’ who is doomed to failure on all fronts, if not from her own failings then from those which are bestowed upon her. The convenience store hostage situation that triggers her living nightmare gives us an officer who is barely holding it together. After she’s shaken off the sweat and ironed-out the nerves, we’ve experienced the distinctly human evolution of a very real and authentic hero: the fear and the adrenaline, the act and its repercussions. Compared with Turner, the likes of John Matrix are emotional cannon fodder.

Bigelow, who has indulged in her fair share of blood and violence throughout the years, lends more than an element of horror to Blue Steel, smartly recalling Curtis’ final girl legacy. Like Laurie Strode before her, Turner grows into her role. The man who stalks her at every turn has as much in common with Michael Myers as he does with the opulent chauvinism of Reganite America. Ron Silver’s deliriously overblown Eugene Hunt is a wealthy Wall Street trader reminiscent of Patrick Bateman minus the satire, a self-styled ‘master of the universe’ with impeccable dress sense and a penchant for tension-relieving workouts who isn’t averse to smothering himself in the blood of murdered prostitutes. Just like Myers, Hunt is a relentless scourge who falls into murder and acquires an immediate taste for it, slaughtering everyone who stands in the way of his female obsession as if determined by the fullness of the moon. Whatever obstacles he faces he immediately overcomes, pursuing his prey with an omnipresence usually reserved for the supernatural. Hunt believes he’s been put on Earth for a higher purpose ― crazy talk for the rationalisation of indiscriminate murder ― and in Turner he believes he has found his kindred spirit.

Silva’s Hunt is an obsessive stalker in the Fatal Attraction mode, though this time the roles are reversed. Like Fatal Attraction, the film can often feel contrived, Hunt turning up everywhere as if by magic, but the idea of male omnipotence in late-20th century society makes it just a little more forgivable. A witness to Turner’s fateful convenience store confrontation, Hunt steals the perpetrator’s pistol, which ultimately leads to her suspension, and when dead bodies begin cropping up all over New York City, all eyes are on the young rookie. That’s because Hunt has been engraving bullets with Turner’s name, leading to her unofficial reinstatement as a faux-detective as a ruse for the mystery killer’s capture. The problem is, Turner hasn’t the foggiest idea who she’s looking for, so when Hunt consciously seeks her out the two begin dating and the plot inevitably thickens.

When night falls Hunt projects the feral animalism of a werewolf, lapping up delicious lakes of crimson and scurrying around in the sacred soil. That Hunt is able to evade police with such insouciance is befitting of such a creature, particularly when Clancy Brown’s Detective Nick Mann is tailing Turner the whole time. Mann becomes Turner’s only ally as a predominantly male cast looks to undermine her at every turn, his professional superiority rarely on display. In fact, when a desperate Turner takes a leaf out of the renegade handbook, her more experienced colleague is duped and handcuffed to a steering wheel. She even jumps into bed with him with a guiltless nonchalance typically reserved for macho stereotypes. At times, the character becomes almost androgynous.

Bigelow would discuss her approach to genre convention in 2017. “What interests me is treading on familiar territory,” she would explain. “With the motorcycles and vampires, it makes the audience comfortable to know that there’s something familiar; i.e., there’s the genre thread through it. Then I try to turn the genre on its head or make an about-face, and just when I make the audience a bit uncomfortable, I go back and reaffirm—”Yes, it’s all right.” But it isn’t necessarily conscious. I am keeping within the sense of something familiar, then trying to expand it, push its limitations. Maybe in the case of Near Dark, which is more like a vampire Western, there’s a bit of hybridization of genre. I also think in Blue Steel there is a mutation that maybe implies a different genre… the use of cliché is not a conscious approach. It’s just a matter of working within a construct that is familiar and then subverting it in order to reexamine it.”

With such an open philosophy towards genre, it’s no surprise that Blue Steel bombed at the box office. The action genre traditionally fulfils male-oriented fantasies, and blokes aren’t generally queuing up to watch a female cop thriller, something that was especially true at the time of the film’s release. What is surprising, particularly with Bigelow at the helm, is that the movie hasn’t received more fanfare in the ensuing years. Blue Steel is one of those movies that can be added to the ‘largely forgotten’ pile, the kind that you might catch on TV, but one that you’re certainly not going out of your way to see. You may vaguely remember it, may have it confused with something else, but thanks to it’s atypical subject matter it has never really sparked the public’s imagination. Even with Bigelow’s rising star and Curtis’ now legendary status, it is rarely discussed, inhabiting a peculiar commercial and thematic void.

Perhaps one of the reasons why Blue Steel has fallen by the wayside is the fact that people tend to assume that it’s just another in a myriad of cop thrillers. That was certainly a preconception I harboured before realising that Bigelow was at the helm (back in 1990 she had nowhere near the stock or relevance that she has gained in recent years). To be fair, such assumptions are somewhat warranted. The majority of characters in Blue Steel are cut and dry, and it often feels like a conventional cop thriller, but in order for Bigelow’s protagonist to break character convention, narrative convention is something of a necessity. Blue Steel is a bitches brew of a movie. It is alluringly cinematic, as stylish as you would expect from a talent like Bigelow, while also inhabiting the murky, smoke-strewn underground of Lustig-esque exploitation cinema. It can be as overblown as an Arnie vehicle, fuelled by the kind of sensational plot developments that are reminiscent of Glenn Close’s infamous bunny boiler Alex Forrest, but it’s the actress at the centre of it all that counts, the notions she embodies that truly shine through.

So next time you enter a discussion about cinema’s most influential action heroes, spare a thought for Jamie Lee Curtis’ Megan Turner. She may not have the blockbuster appeal of Sigourney Weaver’s Ripley or Linda Hamilton’s Sarah Connor, nor the flagrant ass-kickery of Cynthia Rothrock, but what she has is steel in abundance. It’s all in the title, people.

Director: Kathryn Bigelow

Screenplay: Kathryn Bigelow &

Eric Red

Music: Brad Fiedel

Cinematography: Amir Mokri

Editing: Lee Percy