Yuletide horror, genre innovations and real-life serial killers make Black Christmas a deliciously dark treat for the festive season

Black Christmas was one hell of a unique movie back in 1974. Despite its relative anonymity among the big slasher franchises, many regard the film, widely released on the exact same day as Tobe Hooper’s similarly seminal The Texas Chainsaw Massacre in its native Canada, as the first pure slasher. There are plenty of progenitors going all the way back to 1960’s Peeping Tom, a commercial outsider that introduced the POV killer motif, but for many Black Christmas and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, though arriving long before the sub-genre descended into type, before the term slasher had even been coined, tick enough boxes to be considered beyond the limits of mere proto slashers. Both feature human killers who use weapons other than guns, a body count of two or more, a compulsion to kill triggered by environment or events relating to childhood, and a final girl to act as the heroic focal point. There’s also Sergio Martino’s Torso to consider. Since the movie places more of an emphasis on the whodunnit elements more closely associated with the Italian giallo, the film is often overlooked on US shores, but it predates Hooper’s masked killer with its balaclava-wearing villain, John Carpenter’s Halloween with its sex = death motif, and all three thanks to Suzy Kendall’s virginial final girl, Jane. Ultimately, it all comes down to personal opinion, though I doubt we’ll come to a unanimous verdict any time soon.

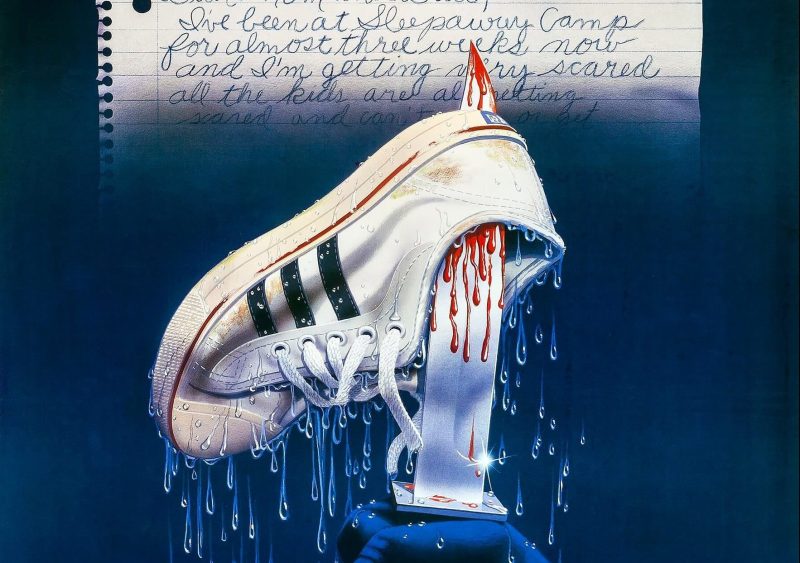

The first slasher to truly genericise was Sean Cunningham’s transparent Halloween derivative Friday the 13th. Despite Halloween‘s popularising qualities, it was Cunningham’s shake and bake cash-in that set the template for the decade of mostly uninspired clones that followed. Sure, it featured a legendary twist, popularising the summer camp setting first glimpsed in Mario Bava’s Bay of Blood aka Twitch of the Death Nerve, another proto slasher that’s very much up for debate, but asides from a series of impressive kills courtesy of practical effects wizard Tom Savini and a legendary, against-type cameo from former American Sweetheart Betsy Palmer as Norman Bates in reverse, Pamela Voorhees, it lacked the technical panache, intriguing characterisation and general integrity of its much worthier predecessors, excelling instead as a fine example of promotional chicanery sold off the back of yet another holiday title. Though they were integral to the sub-genre’s evolution, I don’t regard Black Christmas, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre or Halloween as slashers per se. They’re much too unique and important to the horror genre at large to be burdened with such a generic label.

Of all those movies, Halloween has become most synonymous with the slasher genre due to its astonishing box office success, the kind rarely achieved by independent pictures. This can be accredited to several factors: ‘The Shape”s iconic visage, Carpenter’s unforgettable score and dazzling use of space and shadows and the sheer scope of the franchise going forward, but perhaps most important of all is THAT title, one Carpenter would discuss with Black Christmas director Bob Clark after approaching him about the possibility of making a sequel. “I never intended to do a sequel,” Clark would recall. “I did a film about three years later, started a film with John Carpenter, it was his first film for Warner Bros. (which picked up Black Christmas). He asked me if I was ever gonna do a sequel and I said ‘no’. I was through with horror, I didn’t come into the business to do just horror. He said, ‘Well what would you do if you did do a sequel?’ I said it would be the next year and the guy would have actually been caught, escape from a mental institution, go back to the house and they would start all over again. And I would call it Halloween.”

Though Clark would admit that plenty of filmmakers had already discussed the idea of making a horror movie titled Halloween, including Halloween producer Irwin Yablans and Carpenter himself, there must be some regret on his part that he didn’t bite first, particularly since Black Christmas was the first holiday-themed slasher to receive a wide release (technically, 1972’s Silent Night, Bloody Night, which received only a limited release, got there first, though its mystery elements and Hammer atmosphere detract from its slasher status). The commercial clout of Clark’s title can never be fully gauged since US distributor Warner Brothers changed it to Silent Night, Evil Night for the film’s initial release due to fears that it would be misinterpreted as a ‘Blaxploitation movie’ less than two years on from William Crane’s horror crossover Blacula, but with a box office of only $4,100,000 compared with Halloween‘s estimated $70,274,000 worldwide, Silent Night, Evil Night, which reverted back to the Black Christmas title for subsequent screenings, failed to ignite the public’s imagination on anywhere near the level of its successor, despite being the third-highest-grossing Canadian film of all-time. It would, however, gain a cult following that would become inextricably tied to the ‘silly season’.

Little baby bunting/Daddy’s went a-hunting/Gonna fetch a rabbit skin to wrap his baby Agnes in.

Billy

Today, alternative Christmas movies are everywhere thanks in large part to a cynical 80s revolution that gave us atypical festive forays such as Lethal Weapon, Die Hard and Gremlins, the latter proving so deliciously dark that it contributed to the founding of the PG-13 rating in the US, even being lumbered with a 15 certificate by the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) during a period of censorship hysteria, but imagine how Black Christmas was received by a generation weaned on a diet of schmaltzy redemption and traditional good cheer. The title alone is as blunt as they come, a middle finger to yuletide merriment and fair warning for what exists beneath the commercial wrapping paper. Black Christmas is a lean, mean, exercise in horror that tapped into suburban fears during North America’s serial killer boom, a time when wholly unprepared local law officials feared the day when a random psycho turned up in their locale on a groundless conquest for non-discriminatory human disposal. It was authentic by design too, ditching the lurid, unreal extravagances of Peeping Tom‘s Eastmancolor approach for a rough and ready assault that remains chillingly close to the bone as an unidentified threat wanders the shadowy confines of a sorority house with murder on the mind. Michael Powell may have introduced audiences to that intrusive POV style, making them complicit as shameful voyeurs, but Black Christmas invites us to take part in a worryingly intimate home invasion that remains deeply unsettling for long stretches.

Like Halloween, Black Christmas leaves much of the violence to our imagination, though a series of startling images, like the long, intimate framing of a teenage corpse wrapped in plastic on an attic-bound rocking chair, are sure to stay long in the memory. Clark also makes great use of sound, particularly during the film’s infamous nuisance phone calls, a cacophony of twisted growls and gurgles that speak to it’s equally twisted tagline: If this picture doesn’t make your skin crawl, it’s on too tight. Clark’s script hurls sexually motivated expletives like an evil clown juggling a hot custard pie, the word ‘Cunt’ inevitably removed by the BBFC along with several other crude sexual references that capture the warped detachment of a psychopathic temperament with frightening aplomb. An uncredited Nick Mancuso was hired as the main voice of Billy, though several actors were used to capture the nuisance caller’s multiple personalities, including Clark himself. Clark went to great lengths to create a distinctive voice for his barely glimpsed antagonist, Mancuso even claiming that he would record sessions standing on his head in order to compress his thorax for a more demented sound. Asides from the iconic and truly startling shot of Billy peeping through a crack in a door, when I think of the character, or Black Christmas in general, it’s that voice that pollutes my imagination.

For a villain who is rarely captured from a traditional perspective, Billy sure makes a lasting impression. Mancuso and company’s audio contributions are integral to the movie’s enduring impact, but Clark’s audacious POV style puts you right in the killer’s shoes, particularly during a wildly disconcerting fit of frustration in the barely lit confines of a corpse-ridden attic. There’s nothing more terrifying than the very tangible prospect of emotional collapse, and Clark captures that without a hint of the hyperbolic silliness synonymous with the sub-genre. The passing of time has the propensity to make even the most innovatively terrifying films quaint in hindsight, but I don’t recall a single moment of accidental hilarity in Black Christmas, which, almost half a century on, is a feat in itself. The moments in which we do glimpse Billy, a glimmer of madness peering out of a shadowy void, are just as unsettling, giving us just enough imaginative rope to hang ourselves with. Even Billy’s victims, positioned like festive decorations ironically embellishing the film’s nightmarish scenario, are just as suggestive of a character seeped in chaotic fantasies of the most perverse and unsettling variety.

Oh, why don’t you go find a wall socket and stick your tongue in it? That’ll give you a charge.

Barb

Clark’s decision to leave so much to the imagination, whether determined by budget or otherwise, is one of the reasons why Black Christmas has aged so well, but there are other factors that contribute to the film’s relatively timeless appeal. Stan Cole’s watertight editing certainly helps to set Black Christmas apart from other films under the slasher label, many of which suffer horribly in that regard. The film is also competently and dramatically staged with a cast who prove themselves a cut above your typical slasher fare, a concerted effort on Clark’s part, who felt that college girls had been depicted in a way that lacked “any sense of reality”. Future Lois Lane, Margot Kidder, is particularly compelling as self-pitying wild child Barb, her drunken outburst having teased the murdered Clare prior to her disappearance a taste of the burgeoning talent that would later blossom. The jaw-droppingly stunning Olivia Hussey is also rather impressive as the killer’s eventual focal point, carrying herself with a resilience and quiet dignity redolent of the feminist movement of the 1970s, her character Jess defiant in the face of her traditional-minded boyfriend and an unexpected pregnancy that threatens to derail her occupational independence. Both are a far cry from the generic itty bitties who would soon populate the genre. 2001: A Space Odyssey‘s Keir Dullea is suitably fierce and deeply unlikable as her talented, temperamental and just a little Draconian partner Peter, convincing as one possible culprit for the film’s murders. John Saxon, no stranger to horror or violent whodunnits having starred in what is considered the first ever giallo, Mario Bava’s The Girl Who Knew Too Much, is typically magnetic as the town’s earnest and committed cop Lt. Fuller, holding the whole thing together along with a police force who are suitably unprepared for such a random siege. It’s stellar work all around for such a low-key outing.

Clark achieves minor miracles with a humble setting, refreshingly and expertly navigated in a way that inspires genuine uncertainty, our killer managing an effortless omnipotence that proves almost supernatural despite the film’s grainy, visually relatable presentation. Billy may be a very human threat in his POV invasiveness, but his subliminal nature borders on the feverish at times, particularly during Margot Kidder’s untypically graphic but mostly suggestive multiple-stabbing, our villain leering over her bed like a satanic apparition, all fire and brimstone amid the identity-concealing gloom. Billy, and the film as a whole, prove devilishly elusive, a fact bolstered by Carl Zitterer’s similarly subliminal score, a dreamy, almost hypnotic assault of subtle dread achieved by tying forks, combs and knives to the strings of a piano, thereby warping the sound of the keys. He would later distort those sounds further by recording on audiotape and slowing them down to a dreary, almost dreamlike whisper. It may not have the universal appeal of Carpenter’s Halloween theme or even Harry Mandfredini’s warped verbal motif in the Friday the 13th series, but it is hugely effective, shrewdly complementing the movie’s tone rather than acting as the driving force.

Despite remaining somewhat on the fringes, Black Christmas would gain nationwide exposure almost four years after its initial release following real-life events that would expand on its lore and reputation as a legitimate slice of independent filmmaking. Those same events would also justify the words of critics who had dismissed Clark’s quiet innovator as, in the words of Variety, ‘a bloody, senseless kill-for-kicks feature’ that ‘exploits unnecessary violence in a university sorority house operated by an implausibly alcoholic ex-hoofer.’

In the early hours of January 15, 1978, notorious serial killer Ted Bundy entered FSU’s Chi Omega sorority house through a rear door with a faulty locking mechanism two weeks prior to the film’s network television premiere on NBC’s Saturday Night at the Movies. On what was his final killing spree having inexplicably escaped from custody for a second time, Bundy bludgeoned 21 year-old Margaret Bowman with a piece of oak firewood as she slept before garrotting her with a nylon stocking. In an insatiable splurge before his inevitable capture, he would then beat 20 year-old Lisa Levy unconscious, strangling her, tearing off one of her nipples and leaving a deep bite on her left buttock during a sexual assault undertaken with a hair mist bottle, but Bundy wasn’t done yet. Creeping into an adjoining room, he would then attack Kathy Kleiner, breaking her jaw and deeply lacerating her shoulder, and fellow student Karen Chandler, who suffered a concussion, a broken jaw, the loss of some teeth and a crushed finger. According to detectives the entire ordeal was executed in less than 15 minutes within earshot of 30 witnesses who were somehow none the wiser.

One of the most charming and elusive serial killers in history, Bundy, who would win an army of fans after brazenly protesting his innocence and defending himself in a court of law that he would transform into a media circus, was an uncanny reflection of the killer in Black Christmas, not only through his choice of victims, but due to his sexual motivations and elusive nature. Escaping from a prison library and later through a slim jailcell shaft having purposely starved himself to lose the required weight, Bundy would conceal himself for weeks on end during a nationwide manhunt, committing deplorable, sexually motivated acts of murder with a twisted compulsion that belied his educated, charismatic, almost harmless and somewhat agreeable façade. This was before DNA, CCTV, computer storage and a state-wide network of cooperating jurisdictions, which made the capture of such a high-profile killer extremely difficult, especially in regards to Bundy, a man with a chameleon-like appearance who consistently convinced both citizens and officials as multiple personalities with multiple identities, something the telephone calls in Black Christmas harbour more than a hint of. Had Bundy seen and been influenced by Black Christmas or had Clark successfully foreshadowed one of the most prolific killers in American history? It’s a deeply disconcerting question to ponder.

Let me lick your pretty piggy cunt!

Billy

The twist featured in Black Christmas certainly calls to mind some of Bundy’s escapades beyond his sorority house spree, particularly his ability to evade detection. Taking inspiration from an urban legend known as ‘The Babysitter and the Man Upstairs’, Clark places the film’s killer in the confines of the doomed sorority house, his obscene calls made from telephones located in other rooms. Ultimately it is Peter, having lost control following a failed piano recital and rejection at the hands of Jess, who is fingered for the crimes and killed during a seriously tense and creepy climax of sobering proportions. Later, Jess having been sedated and left to recover, Clark hits us with a Bundy-like twist that suggests that Peter wasn’t the killer, that the killer roams free, the prospect of further destruction his sole motivation in the absence of law enforcement who, much like real life, seem ill-equipped to deal with such a diabolical mind. We don’t know if Jess dies for sure, but it’s very likely, particularly when, during the film’s end credits, we hear the telephone ring unanswered. Until that juncture, Billy has always followed the act of murder with a phone call. There’s no one left to taunt by that point, which might suggest that the ringing is non-diegetic, existing in a residual sphere that lives on in the viewer, but when it comes to the likes of Billy, would an absence of victims really be enough to halt such a deep-rooted compulsion?

The final moments of Black Christmas, hinting at the suburban horrors lurking beneath the festive veneer, are truly disconcerting, once again revealing benign grotesqueries that somehow remain undetected. It is a beautifully ironic parting shot with a deeply troubling underbelly that Hitchcock at his most whimsical and macabre would have been proud of. It’s in no hurry either. It just hangs there, quietly zooming out of view like a desecrated dollhouse decorated with little dead people. Those end credits are some of the most caustic, reflective, and downright disturbing in the entire genre. As an audience we’re allowed to linger and soak up the aftermath of heinous crimes that remain unpunished, that could be lurking on the fringes of our very own neighbourhood, taking place in the adjacent building, perhaps in the very next room. In that moment a singular notion infected my being: These things happen. They’re happening right now. And as long as humanity exists they will continue to happen. Imagine contemplating such truths during America’s serial killer boom, a time when motiveless murderers inhabited an almost invincible realm, when regular people were utterly vulnerable to the whims of unflinching, premeditated horrors. Clark tapped into something raw, contemporary, and utterly disquieting. It’s no wonder the film lives on almost a half-century later.

Black Christmas will never enjoy the universal status of some of the major horror franchises, despite a couple of reboots and a broad re-evaluation that has been mostly positive. Thanks to its mysterious, open-ended qualities and subliminal approach to horror, it doesn’t possess the visual motif that sets the genre’s most infamous masked killers apart. It doesn’t have the instantly recognisable score, the sustained legacy or the abattoir of creative kills that gore hounds crave. It does, however, hold a rather prominent place in the history of not only the slasher genre, but horror in general, Clark’s underappreciated gem retrospectively hailed as one of the most influential entries in a sub-genre that it doesn’t necessarily belong to, but took great strides in establishing. That the slasher would become so popular during its golden age peak is testament to a film that fittingly spent many years clinging to the shadows. Like an elusive serial killer with a singular intension, Black Christmas would eventually make its mark and then some.

Director: Bob Clark

Screenplay: A. Roy Moore

Cinematography: Reginald H. Morris

Music: Carl Zittrer

Editing: Stan Cole

I LOVE “Black Christmas” (just had a conversation about the film with my young friend & co-worker Cortlan:-); one of those films that start out intense and then does a slow burn throughout, which I love (I think “When a Stranger Calls” does a similar thing, but I don’t like it as much). Plus this film has Margot Kidder, who I decided that if there was ever a Hollywood actress I’d marry, it would be Kidder, and only Kidder:-). Another thing is that John Saxon’s in this piece, and I feel his role here sets up his later effort in the 1984 “A Nightmare on Elm Street”, and in an interview once Saxon said as much.

But for sure, I love how this film is left to the imagination. More creepy than scary, and I just dig the entire atmosphere of the film.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hey Eillio,

Absolutely. All about the atmosphere this one. Not your typical blood and guts slasher as many assume, and highly influential. Engaging characters too, which strengthens the movie at every level. It’s surprising how well it has aged considering the budget.

LikeLiked by 1 person