John Badham’s energetic comedy delivers a healthy dose of satire and a buddy pairing for the ages

Can you separate the artist from the person? In an era of great political division it’s a question many of us have pondered. Former Smiths frontman Morrissey has recently come under fire for his outspoken political views, and when you go around making comments like, “Everyone ultimately prefers their own race,” it should come as no surprise when former band mates distance themselves from you and everything you stand for. It’s rather ironic since Morrissey was once a beacon of hope for the downtrodden youth of Thatcher’s Britain, and there’s no denying the relevance of his words back then, which were lyrical and poignant and blossoming with the dead-on contrarianism of Oscar Wilde. Morrissey has always been outspoken, becoming contentious for all the wrong reasons in recent years, but people have the right to alter their beliefs. Their art becomes public property, but the person remains an ever-evolving individual. Whether we continue to agree with them is besides the point.

Over in the US, the same can be said of actor James Woods. Many view 21st century Woods as a mean-spirited bigot, his outspoken social media activity even landing him a ban on Twitter. The main problem is the current definition of ‘freedom of speech’ and what it stands for in the minds of many. The freedom to express one’s opinions is essential to democracy, but using language that alienates and discriminates jeopardises the freedom of others, opinions masquerading as democratic free speech when in reality millions must suffer as a consequence. Freedom of speech is the right to stand up for oneself, not the right to discriminate against whoever you wish. It’s like a kid who wants to be treated like an adult with none of the responsibility.

Whatever your opinion of Woods, there’s no doubting the guy’s acting ability. Just think of the films he’s starred in over the years, from iconic cult movies like David Cronenberg’s techno-surrealist body horror Videodrome to rewarding, low-key affairs such as Stephen King horror compendium Cat’s Eye (Woods was made for King’s cynical brand of short fiction). He even threatened to steal the show going up against peak De Niro and Joe Pesci in 1995‘s whirlwind gangster epic Casino. Drama, comedy, action, sci-fi, horror ― he’s done it all at one time or another, and he rarely, if ever disappoints.

Despite such a breadth of diversity genre-wise, Woods is typically cast to fit a very particular profile, roles that cater to his slippery, hyperactive energy. In Videodrome the actor plays a sleazy purveyor of snuff-tinged pornography; in Cat’s Eye a neurotic smoker battling nicotine addiction, a role he would marginally tweak for his inspired turn as a cocaine-addicted real-estate hustler in Harold Becker’s 1988 drama The Boost. In Casino he played parasitic pimp and fevered drug addict Lester Diamond, a master manipulator dripping with shyster bravado. These roles were essentially variations of the same breed of character. When you hire James Woods, you get James Woods, regardless of the specificities.

I DON’T WANT YOU INSIDE MY SKIN, YOU UNDERSTAND? It’s private! What’s in there belongs to me! You’re not gonna learn what it means to be a cop by eating hot dogs and picking your teeth and asking stupid questions. We live this job. It’s something we are, not something we do! Every time a cop walks up to a car and has to give a speeding ticket, he knows he may have to kill someone or be killed himself. That’s not something you step into by strapping on a rubber gun and riding around all day. You get to go back to your million dollar beach house and your bimbos and your blow jobs and you get 17 takes to get it right. We get one take. It lasts our whole lives. We mess it up and we’re dead.

John Moss

It’s safe to say that, on the whole, Woods tends to play soulless bottom feeders, icky creations who explore the uglier side of humanity, but there’s typically an element of gallows humour involved, which makes him a perfect fit for comedy, more so the action comedy traditions of the late-80s/early-90s. In John Badham’s largely forgotten and sorely underrated buddy flick The Hard Way, a movie which possesses the kind of onscreen chemistry most can only dream of, he has the frenetic, cynical hard ass down to a fine art, riding a tenuous line between endearing comedy and complete emotional breakdown. The film was originally set to star Gene Hackman and A Fish Called Wanda‘s Kevin Kline, which in itself is a mouthwatering prospect, but it’s hard to imagine the two living up to the film’s eventual pairing. I hope casting agent Dan Ursu received a much-deserved bonus for this one.

The second part of our duo is just as adept at portraying comedic hyperactivity, only the pint-sized Michael J. Fox typically excelled as the good-natured kid skidding from one calamity to another. Marty McFly is all about slipping and sliding, skidding from one impossible situation to the next with a boy next door charm that was simply irresistible. Teen Wolf, Doc Hollywood, The Frighteners ― they all featured variations of the same character. Again, when you hire Michael J. Fox, you get Michael J. Fox; like Woods, he does what he does better than anyone else. Admittedly, I never would have thought of pairing the two actors in a comedy movie. They’re fundamentally different in the sense that Fox was the plucky young underdog and Woods the grizzled, maladjusted type, but they possessed the same boundless energy. The two together had the potential for overkill.

I needn’t have worried. The two play off each other so naturally it’s like poetry in motion. Woods does what Woods does best only with the volume turned up to eleven. Sometimes it feels like he’s performing a send-up of himself, as if he’s consciously accentuating every trait synonymous with his typical onscreen persona ― ironic since his character in The Hard Way, a no-nonsense detective named John Moss, is a closed book who refuses to confront himself. Moss lives his life like a shark, embracing a constant state of activity in order to avoid self-analysis. The genius of The Hard Way is that Fox’s character, Nick Lang, is a hotshot Hollywood actor living in a bubble of privilege who seems obsessed with self-analysis, self-improvement, anything to do with self, one who is assigned to Moss during a very personal, high-profile case. His purpose? To imitate everything Moss does in preparation for his latest role. Moss couldn’t have picked a worse time to quit smoking.

For Moss, looking at Lang is like looking into a none-too-flattering mirror. Everything he yearns to avoid about himself is right there in front of him, pecking away like a pigeon at his ankles, minute after minute, hour after hour. Not only does Lang record everything on a highly intrusive Dictaphone, he sifts through Moss’s personal belongings, copies his expressions, his mannerisms, the way he eats, and the worst thing about it is it’s all a game to Lang. Today he’s playing cops and robbers, tomorrow he’s lording it up in his disgustingly opulent mansion in the Hollywood Hills, surrounded by vegan food platters, gorgeous models and a whole entourage of obsequious assistants reassuring him that his shit smells like potpourri.

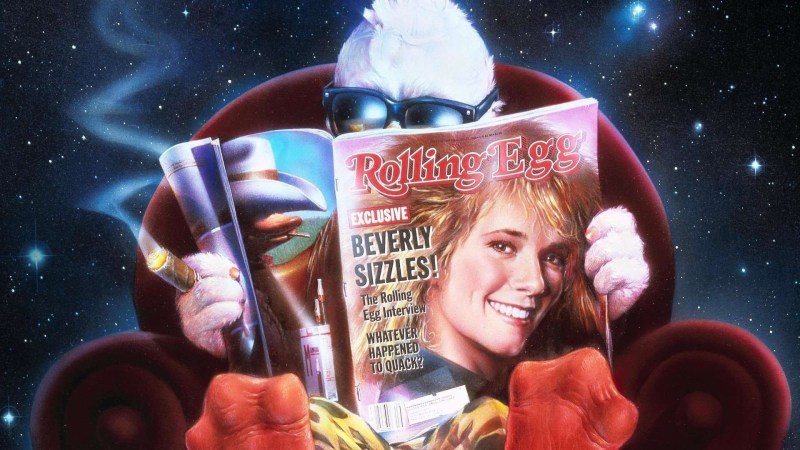

In the ultimate irony, Lang is famous for playing Indy-style hero “Smoking” Joe Gunn, a universally lauded character who always prevails, despite the kind of impossible odds that simply don’t apply to the real world. Moss is the antithesis of this. On the streets he can’t do right for doing wrong. He is too driven, too reckless, and as he so passionately expresses in one of the film’s funniest exchanges, he doesn’t get 17 takes to get it right. His romantic life is even more of a catastrophe thanks to his girlfriend’s distrusting but adorable daughter Bonnie (Christina Ricci). Naturally, loverman Lang is great with kids, even becoming a confidant to Bonnie’s conflicted mother, Susan (Annabella Sciorra). It’s a wonderful set-up that results in so many classic moments, forging the kind of friendship that doesn’t come easy, and as a consequence will surely last forever.

Sciorra is typically captivating as the down to Earth, fiercely independent woman caught in the middle, more than holding her own as the anchor tasked with stabilising the film’s relentless siege of action/comedy. Not the easiest role when faced with two high-calibre personalities and a screenplay catered to their inimitable charms, but she’s the heart and soul of this movie a times, and she’s such an effortless talent who holds the lens so naturally. Susan is the essential ingredient that unites our two polar opposites. There’s a wonderful scene involving Woods and Fox in which Lang imitates Susan in a bar and challenges Moss to open up to him. Moss thinks he needs Lang like he needs a pimple on his ass, but in reality he lacks the new age philosophies required to land the woman of his dreams, and, begrudgingly, that’s where Lang comes in.

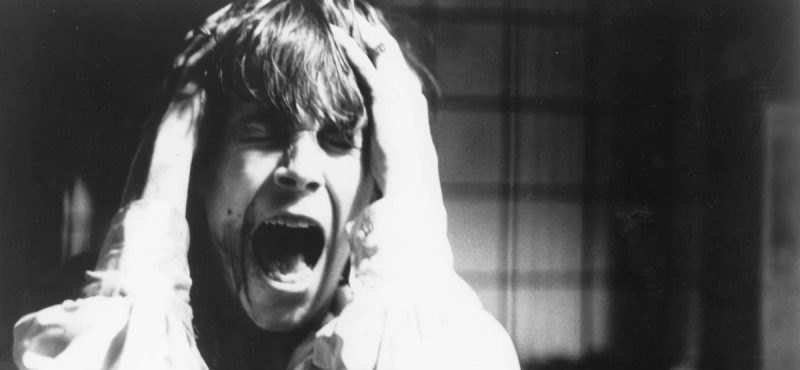

The Hard Way was something of a digression for Fox as he eased his way out of the adorable teen category. He’s essentially the same plucky young underdog, but being a man of wealth and leisure he has to earn that title, which isn’t easy in a precinct that includes energetic loudmouth Billy (LL Cool J), a brash alpha cop who quickly makes Lang the butt of the joke, prodding Moss with a stick at every opportunity. Lang wants to be taken seriously as an actor but isn’t quite prepared for the reality of life on the streets. He may be a superhero in the public eye, but in the concrete jungle he’s easy prey, a fact beautifully outlined when Lang, a cop in the eyes of lunch date Susan, is confronted by some armed thugs on the subway with only a rubber gun to protect his ass. “Somebody call a cop!” Lang shrieks as the bad guy closes in on him. “I mean another cop… besides me!” It’s an absolutely priceless scene that only Fox could deliver.

In Back to the Future, Fox is the courageous little scamp overcoming seemingly insurmountable odds. In The Hard Way he begins as a helpless coward who quickly discovers that the art of imitation and make-believe doesn’t hold up in the bad lands of New York City, regardless of how great of an actor you may be. It’s not like learning lines for an upcoming feature, you have to live and breath the cop profession. There are no crash courses, no second takes. Hollywood may be a fickle mistress ready to discard you at a moment’s notice, but out on the streets it’s life or death.

Ironically, Fox would face very serious real-life issues later that year after displaying symptoms of early-onset Parkinson’s, a disease that would rob audiences of one of Hollywood’s shining lights at the very peak of his powers. Fox wasn’t officially diagnosed until 1992, and his turn as Nick Lang is one of the actor’s last great, unaffected comedy performances. Given what seemed like a life sentence at the age of 31, Fox would turn to the bottle, toiling with years of depression before embracing sobriety and finally going public with his condition more than a half decade after his diagnosis. Fox would continue to pull off fine performances, particularly as seedy paranormal investigator Frank Bannister in Peter Jackson’s cruelly underappreciated horror comedy The Frighteners. He would also find success in the long-running American sitcom Spin City, returning to the medium that triggered his meteoric rise. Since Fox typically played frenetic characters in perpetual motion, the actor was able to disguise his illness for many years. It is testament to his determination that was he was able to embrace the mainstream when the temptation for many would have been to go into hiding and stay there.

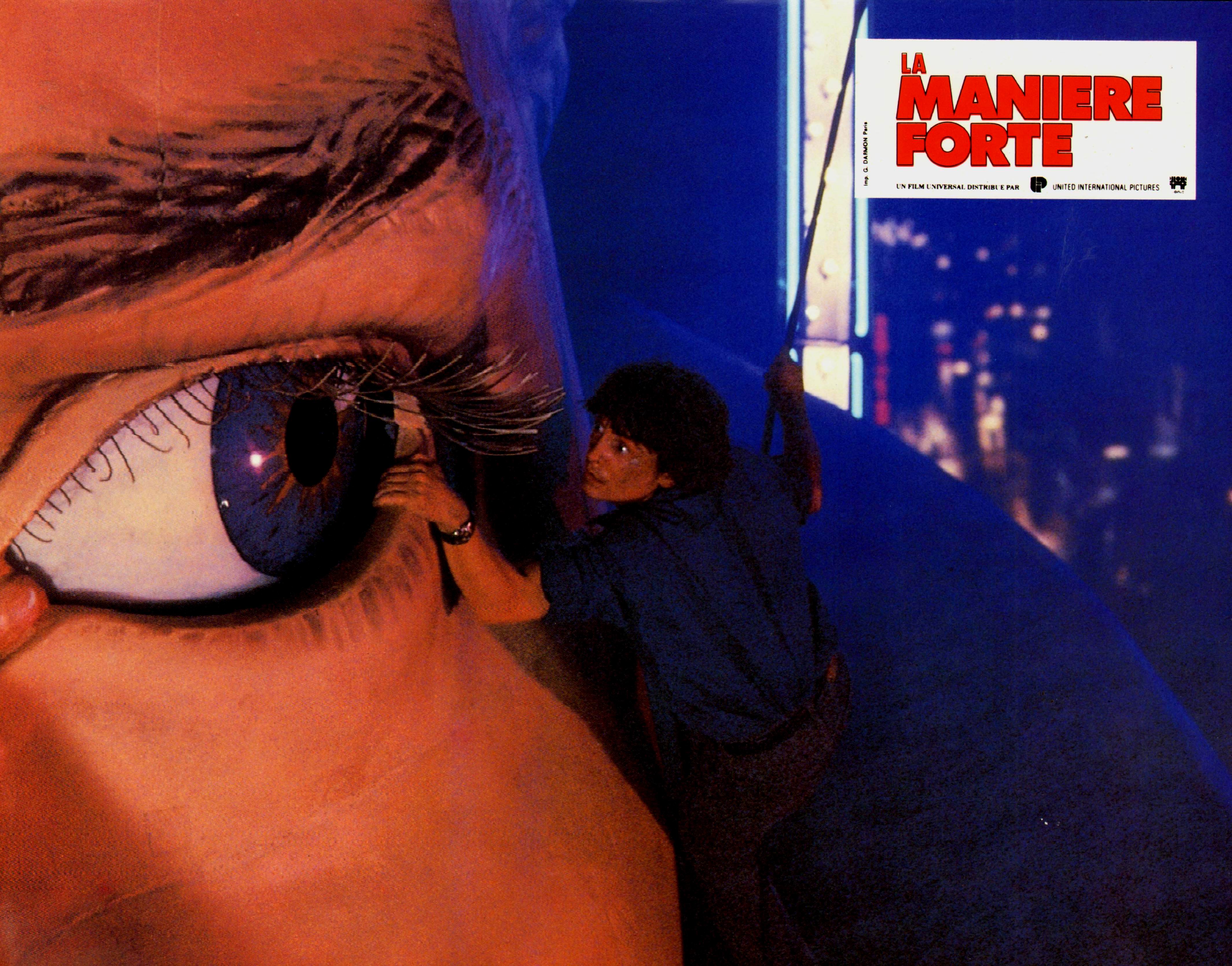

Today, you don’t hear much love for The Hard Way, at least not to the same degree as other mainstream comedies, but for me it stands shoulder-to-shoulder with countless movies that have achieved classic status while The Hard Way has been reduced to something of an also-ran. Granted, the movie’s action narrative is a tad dated and feels a little tacked-on at times, but Stephen Lang is exquisitely psychotic as the morally conflicted and utterly meticulous ‘Party Crasher’, a renegade serial killer who informs the cops of his intentions before embarking on cat-and-mouse chases for the sheer thrill of it. In Moss he finds the perfect foil, the Batman to his Joker. It’s all a little cliché at times, and Lang’s dark side can come across as a little jarring given the screenplay’s otherwise jovial antics, but you can’t knock the film’s more self-aware action sequences, particularly its super-tense, deliciously ironic climax, one that sees Fox hanging from a giant 3-D billboard for his coming attraction ‘Smoking Gunn II’. Rarely has such transparent irony proved so rewarding.

Somebody call a cop! [Gunfire sounds] I mean another cop… besides me!

Nick Lang

The trailers for Lang’s movie within a movie are absolutely priceless. ‘Smoking Gunn II’ is a shameless rip-off of the Indiana Jones series with a theme song that sounds suspiciously like that of Alan Silvestri’s Back to the Future score. The whole movie is a beautifully crafted satire on the trappings and extravagances of Hollywood in a way that is never cynical. The script never criticises its characters on any serious level. It takes what are essentially stereotypes and makes them human. Beyond the standard action fare and side-splitting moments, it forges characters who are somehow rich in catharsis, who are rounded and ultimately relatable ― the vital ingredients of any successful odd couple feature. Moss and Lang are flawed, self-absorbed, borderline-reprehensible at times, but it’s the imperfections that endear us to them so strongly, their capacity to win each other over against all odds that makes The Hard Way such a joyful experience.

Moss represents the worst in all of us, but there’s a part of him that longs for love and happiness. Lang begins as a total schmuck, a phoney who turns up at Moss’ precinct dressed like Serpico, sporting shades and a fake moustache in some lame attempt to remain incognito. He basically fulfils every last stereotype New Yorkers hold against their airy, West Coast compatriots. What’s worse, Moss is taken off the case to babysit the privileged cretin hanging around the precinct like a kid waiting to play cops and robbers, and the captain doesn’t want to hear Moss’s protestations. He’s more interested in getting an autograph for his star-struck wife. Lang is a clown to everyone but himself, but when Moss sets him up and sends him packing with a startlingly cruel prank that crudely reveals the extent of his resentment, he returns for a much-needed dose of redemption. He certainly learns the hard way.

There’s nothing particularly unique about The Hard Way, which is presumably the reason why it seems to have shrunk in stature after a rather impressive box office return of $65,000,000 and almost universal critical acclaim. The Party Killer subplot is as generic as they come, and by 1991 the odd couple buddy cop formula was already a little long in the tooth, but The Hard Way thrives on the sheer energy and irresistible camaraderie of its lead players, who are clearly having so much fun revelling in parts that were tailor-made for them, which very few could have pulled off like Fox and Woods. There’s a fair bit of filler that moves the plot forward, making the action a little flabby at times, but you’re so invested in the movie’s characters and their back-and-forth struggles that it hardly matters. Just watch the scene when Moss and a newly-recruited Lang stop off for a nitrate-heavy, ‘Frog Dog’ lunch, only for Moss to lose his shit when Lang continues to imitate his every action. There’s a tension to their comedy, an expectation that leaves you in a perpetual state of anticipation. Watching them is like watching a lit fuse racing towards explosion, and the fuse is endless, the explosions plentiful.

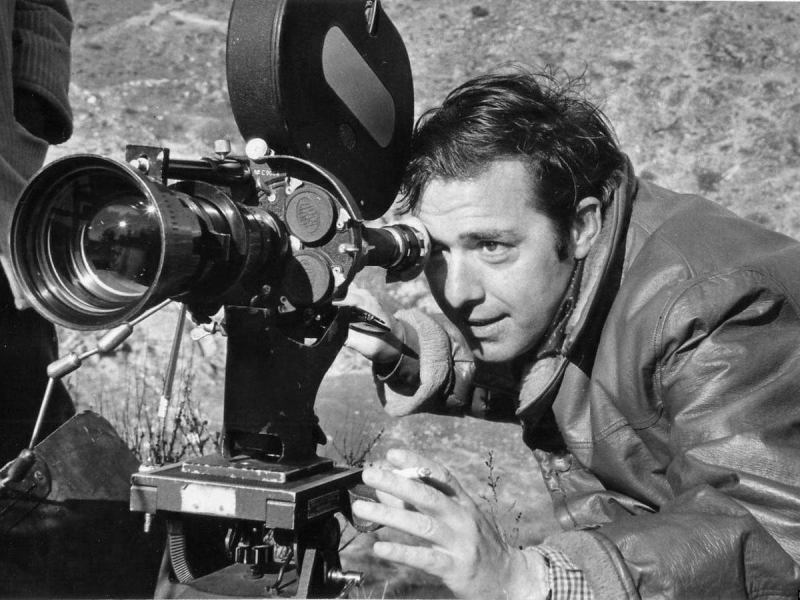

Badham, a director who can add Saturday Night Fever, 1979‘s Dracula and War Games to his back catalogue, has proven himself a wonderful genre filmmaker over the years, with a special knack for forging flawed, relatable characters. Some, like Saturday Night Fever’s talented delinquent Tony Manero, are very much rooted in reality, rich with conflict and motivated by a burning desire to cast off the stifling preconceptions of a society that rejects them almost as a birthright. The Hard Way doesn’t aim for such depth, is a completely different animal, but the fact that we are equally as endeared to characters who are absolutely steeped in convention is a testament to Badham’s abilities, but more so to the skill and likeability of his lead players. It may be hard for some to embrace Woods given his recent antics, but sometimes you don’t have to separate the person from the artist. Someone else does it for you.

Director: John Badham

Screenplay: Daniel Pyne &

Lem Dobbs

Music: Arthur B. Rubinstein

Cinematography: Donald McAlpine &

Robert Primes

Editing: Tony Lombardo &

Frank Morriss