Offering a political analysis of the war correspondent subgenre of the early 1980s

During the first half of the eighties, Hollywood released a series of deeply cynical prestige flicks about war correspondents in Asia and Central America that say plenty about the country’s complicated relationship with a free press. After Woodward and Bernstein took down a President and then did it again on the big screen in All The President’s Men, most of the American public decided that journalists could save the day. The dynamic duo would inspire a generation of reporters to hunt for a scoop of the same magnitude, but with the end of the Cold War, the public once again looked at reporters like bartenders, another less-than-respectable profession of serving up the distraction of the day. Roger Ailes understood this and knew he could build an empire with the sweetest of all lies, that the truth was simply what his audience wanted to hear.

That would come later, and the election of Ronald Reagan didn’t instantly cure the country’s hangover from the seventies. Most of what we celebrate as quintessential trends of the era, like a focus on suburban white kids and jingoistic bloodbaths, didn’t become apparent until the middle of the decade. And in one particular subgenre, the seventies stretched right into 1986, as studios thought they’d score hits with tales of war correspondents running around places most Americans couldn’t find on a map.

What’s strange about these pictures is they seemed to disregard the rest of the culture at large. Spielberg and Lucas were dominating the box office, and the nation’s PTSD from Vietnam and social revolutions were subsiding into a cloud of brand-new delusions like trickle-down economics and welfare queens. Still, this subgenre made waves at the box office and won awards, which meant someone was still hungry for a degree of moral ambiguity and left-wing pathos.

The first of these was Peter Weir’s The Year Of Living Dangerously (1982), based on the Australian novel of the same name, and the movie plays like a rough draft of a lost Graham Greene novel. It’s centered around the failed communist coup in Jakarta during the sixties, starring Mel Gibson as a correspondent for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, and Sigourney Weaver as a British Embassy employee. The movie suffers from its competing desires to deliver both old school glamour and an enlightened re-telling of that country’s unrest. It does plenty of both, without ever quite hanging together.

To Weir’s credit, he doesn’t shoot Jakarta like a travelogue, with widescreen vistas full of exotic wildlife. He films the city at street level as if it was a place where people lived. But the movie is structured as a coming of age story for Gibson, a young reporter trying to land a scoop. And how Gibson comes of age is by realizing that reporters are at best, irrelevant.

Upon arriving in Jakarta, he’s connected to Billy Kwan, an Indonesian dwarf who works as a fixer and photographer, played by the American Linda Hunt, in a bit of stunt casting that wouldn’t happen now. Kwan is the shadow protagonist here, the person with the most to lose, who drives most of the action as they uncover the coup that’s brewing. In a better world, Kwan would be the lead, and in some ways, Gibson would be Kwan’s antagonist here, instead of merely his shitty Aussie pal.

That said, Weir hardly positions Gibson as the white savior here, making it explicit that his naivete and ambitions get people killed. Gibson is still far more sensitive to the locals when compared to the other Western journalists, who are painted as either decadent or clueless. Michael Murphy plays the most clueless of dirtbags here, and it was not the first time he’d play the face of compromised and ineffectual American power.

With Kwan’s help, Gibson starts posting bombshell stories about the country’s civil unrest, driven by famine and communist protests of then-President Sukarno. His reports seem to matter little to the situation on the ground, beyond building Gibson’s reputation. Kwan even plays Cupid here, setting Gibson up with Weaver’s mysterious Brit siren. Their affair is one of the movie’s great strengths, rendered with both heat and sensitivity, as Weir, Weaver and Gibson understand the best romances remain mysteries of a kind, played out in the actors’ faces and body language. Modern audiences are often too literal-minded to appreciate that the fastest way to kill sexual chemistry is to explain it.

As the country falls into chaos, Weaver admits to being a spy to warn Gibson he needs to leave Indonesia, since an arms shipment to the communist rebels will start a full-blown civil war. Rather than leave, Gibson goes public with the story, betraying both Weaver and Kwan by doing so. Despondent, Kwan decides to risk openly protesting President Sukarno by hanging a sign from the window of an international hotel and is promptly killed for it. Undeterred, Gibson tries to chase the next scoop, only to be blinded by the police, and barely makes it to the airport, where he’s reunited with Weaver on a plane out of the country.

When Weaver embraces him, it’s less out of passion than a kind of maternal relief that he was still alive. Their final moment felt like a curdled surrender rather than any kind of redemption. What’s so fascinating is that Weir, by being smart and sensitive about the reality of Indonesia at the time, muted any emotional satisfaction in watching Gibson survive. He might have come of age, but too late to do anything with that maturity.

Here, the Western reporters were simply another kind of colonial force, mining the country for dramatic tidbits for the folks back home. The actual history saw the communist coup foiled, and the government’s retaliation devolve into mass killings of innocent citizens, paving the way for the military dictatorship of President Suharto, which would last from 1968 to 1998. And all of Gibson’s reporting is left as an act of ambition, not some way of holding the powers that be accountable.

Somehow this became a minor hit in the States, and further solidified the movie star status of both Gibson and Weaver, with Hunt winning the Oscar for Best Supporting Actress. Afterward, Weir would land a movie about a cop going undercover in Amish country, and deliver the Harrison Ford hit, Witness. The year after The Year of Living Dangerously was released, MGM released a far less complicated action drama about war correspondents in Nicaragua.

Under Fire was directed by Brit journeyman Roger Spottiswoode, and co-written by Ron Shelton before he found his gift for delightfully literate sports movies, it’s perhaps the oddest of the bunch, feeling the most like a run of the mill programmer rather than anyone’s big swing for awards season. The movie casts Nick Nolte as a veteran photojournalist that hops from one hot spot to another, often running into American colleagues that stretch from a mercenary (Ed Harris) to prestige correspondents like Gene Hackman and his sometimes girlfriend, Joanna Cassidy. Nolte clearly has feelings for Cassidy, and the love triangle isn’t mined for any dramatic fireworks. Instead, Hackman and Cassidy break things off so Hackman can take a big network gig and Cassidy and Nolte begin their tryst, with Hackman only shrugging at losing this game of musical beds.

Where the movie’s conflict brews is in how Nolte and Cassidy will cover the communist uprising and the corrupt, American-supported dictator in Nicaragua. Over the course of their time covering the battles, Nolte and Cassidy fall for the communist rebels, in the face of the dictator’s brutal crackdown, complete with truckloads of dead “rebels,” who look a lot like bystanders. Even worse, it turns out Nolte’s old pal Ed Harris is killing those innocents on behalf of the American way. By the time our stars get the chance to meet the rebel’s Messianic leader, it’s pretty clear who audiences should be rooting for here.

But when they finally reach that rebel leader, he’s already dead, which could be a decisive blow to their cause. So the rebels want Nolte to stage a photograph to make him look alive, and for Cassidy to back up that version with a print story. If they don’t, Americans will supply the dictator with all he needs to break the insurgency for good. So they agree to produce this propaganda, and sure enough, the Americans stay on the sidelines.

Hackman soon arrives in Nicaragua to interview that rebel leader for his network, only to realize that his ex and his good friend are selling a lie. Hardly Hackman’s finest hour, his basic performance here remains a marvel. When he unloads on Nolte for lying, he’s a deft enough performer to hint that his rage is as much about Nolte sleeping with his ex as it is for the professional malpractice.

Nolte and Hackman call a truce to continue to cover the civil war, and Hackman ends up dead when the dictator’s forces don’t discriminate between rebels and reporters. Nolte has the footage of his best friend’s murder and has to escape government-held territory in one of the movie’s many competently staged set-pieces. Spottiswoode shows chops at spatial tension here, setting up a myriad of threats for Nolte as he tries to escape.

Nolte eventually delivers proof of his pal’s murder and the communist rebels, known as Sandinistas, are victorious. If “Sandinistas” sound familiar, that’s because the US would eventually pull off a complex money-laundering scheme to fund their opposition, the Contras, so they could slaughter as many Sandinistas as possible, in what came to be known in historical footnotes as the Iran-Contra scandal.

But at the end of Under Fire, Nolte and Cassidy embrace, and celebrate the communist takeover of Nicaragua. If that ending seems strange for the decade, it was. But the movie has even stranger things to say about journalism. Rather than being corrupt and ineffectual, Cassidy and Nolte are noble and help turn the tide, with a lie. They don’t succeed by a commitment to the truth, but by burying it as an inconvenience.

It undermines the idea that war correspondents’ first responsibility is to be a reliable witness, and perhaps in the face of such stakes, that doesn’t seem sufficient. But the lack of ambiguity about what Nolte and Cassidy do is disturbing. It’s a furthering of the idea of a “good” Western intervention into other countries, which suddenly does feel very apt for the era. As for the movie, it did middling business, and true to its ambitions, it garnered no Oscar attention save a nomination for Jerry Goldsmith’s score, which Tarantino would lift for a sequence in Django Unchained. The following year, the biggest hit of the subgenre would arrive.

Roland Jaffe’s The Killing Fields is based on the true story of the New York Times correspondent Syd Schanberg (Sam Waterson) and his Cambodian colleague Dith Pran (Dr. Haing S. Ngor), as they face the revolution and terror of the Khmer Rouge regime. The Khmer Rouge were Cambodian communists that upon assuming control of the country, inflicted a genocide of dissidents of such magnitude that every right-wing pundit cites them anytime a liberal says something mean online or suggests spending two cents on the poor.

The movie begins with Waterson in Cambodia trying to report Nixon’s illegal bombings there, since Tricky Dick thought it would secure an early and more generous peace with the North Vietnamese next door. Instead, the bombings destabilized the country and paved the way for the Khmer Rouge to assume control. While this is mentioned to assuage liberal viewers, it’s not adequately dramatized, and not nearly as detailed as the communists’ brutality.

The movie’s depiction of atrocities aren’t inflated, but it operates as an anti-communist screed first and foremost, and an effective one at that. Roland Jaffe does great work staging the civil upheaval, letting the camera move through the violence as a person on the ground, without merely roaming around it like a pseudo-documentary crew. There are traces of inspiration for the well-framed long takes of Children of Men here, and keeping the ravages at human-eye level works incredibly well.

Waterson’s earnest exasperation is perfect here, right alongside a young John Malkovich, playing a combat photographer with an industrial-grade bullshit detector. He so often plays the corruption at the heart of a movie, it’s a nice reminder he can play its conscience too. The Killing Fields works best as the old regime falls to the communists, and Waterson tries to get Dith Pran out of the country since genocidal regimes don’t look kindly on locals that help the New York Times broadcast their excesses.

Waterson does manage to get Pran’s family out, but Pran decides to stay and help Waterson a little longer, hiding in the French embassy. As the country crumbles further, Waterson, Malkovich and Julian Sands all hustle to forge a British passport for him. This fails, and Pran is sent to a re-education camp, where the horrors will give anyone pause about stressing “right-thinking” over free-thinking. Pran is the heart of the picture, played by Dr. Haing Ngor, a non-professional who survived the Khmer Rouge himself and never registers a false note here.

But the movie certainly does. Once Waterson returns to the States, he attempts to get his old pal out of the country by… writing letters, while his Cambodian reporting wins award after award. And how the movie struggles to dramatize his guilt, by showing him mope about his lush New York apartment listening to opera. In one way, it’s a very modern attitude, to think if privileged people just felt bad enough about themselves, the world would magically improve all by itself.

Meanwhile, the movie keeps cutting back to Pran’s escape attempts from the re-education camp and the country, which could stand on its own as a bone-chilling survival movie. This only makes the desperate attempts to center the story on Waterson increasingly ridiculous. It’s hard to watch Pran climb over a mound of skeletons and then care about Waterson making sad eyes in his bathroom mirror.

As great as the Pran sequences are, the movie does little to explain the continued carnage after the Khmer Rouge assumed power, barely mentioning the border war between Cambodia and Vietnam. This continues the great tradition of the West shrugging off wars where it can’t at least star as the great villain. Eventually, Pran finds some soldiers who have their own misgivings about the pace and fever of the revolution, and with their help, he escapes to a refugee camp, and Waterson soon learns his friend is still alive.

As emotionally effective as their reunion is, it can’t help but feel cheap. Jaffe decides to end with John Lennon’s “Imagine,” a song that seems all at once overblown and insufficient. The song’s hazy utopia feels like shorthand for toothless liberal aspirations everywhere, and while this American’s friend got out, there’s a whole country still in tatters.

Ngor won the Oscar for Best Supporting Actor, and the movie would win Best Cinematography by Chris Menges and Best Editing by Jim Clark. It would also serve as the terrain for one of the great one-man shows of all time, Swimming To Cambodia, where Spalding Gray would turn his small role as a useless American official into a hilarious, far richer and more accurate account of the conflict (and his own neurosis).

But it’s hard not to wonder what it has to say about journalism, other than its ability to put its sources and practitioners in danger. It wasn’t American journalists that rescued their colleague; it was that man’s own canny survival instincts. It may have fed the era’s distaste for communist excesses, but it continued to erode the idea that there was any use for war correspondence. The best of this bunch is also a noted outlier, both in terms of approach and success, as well as the only one directed by an American.

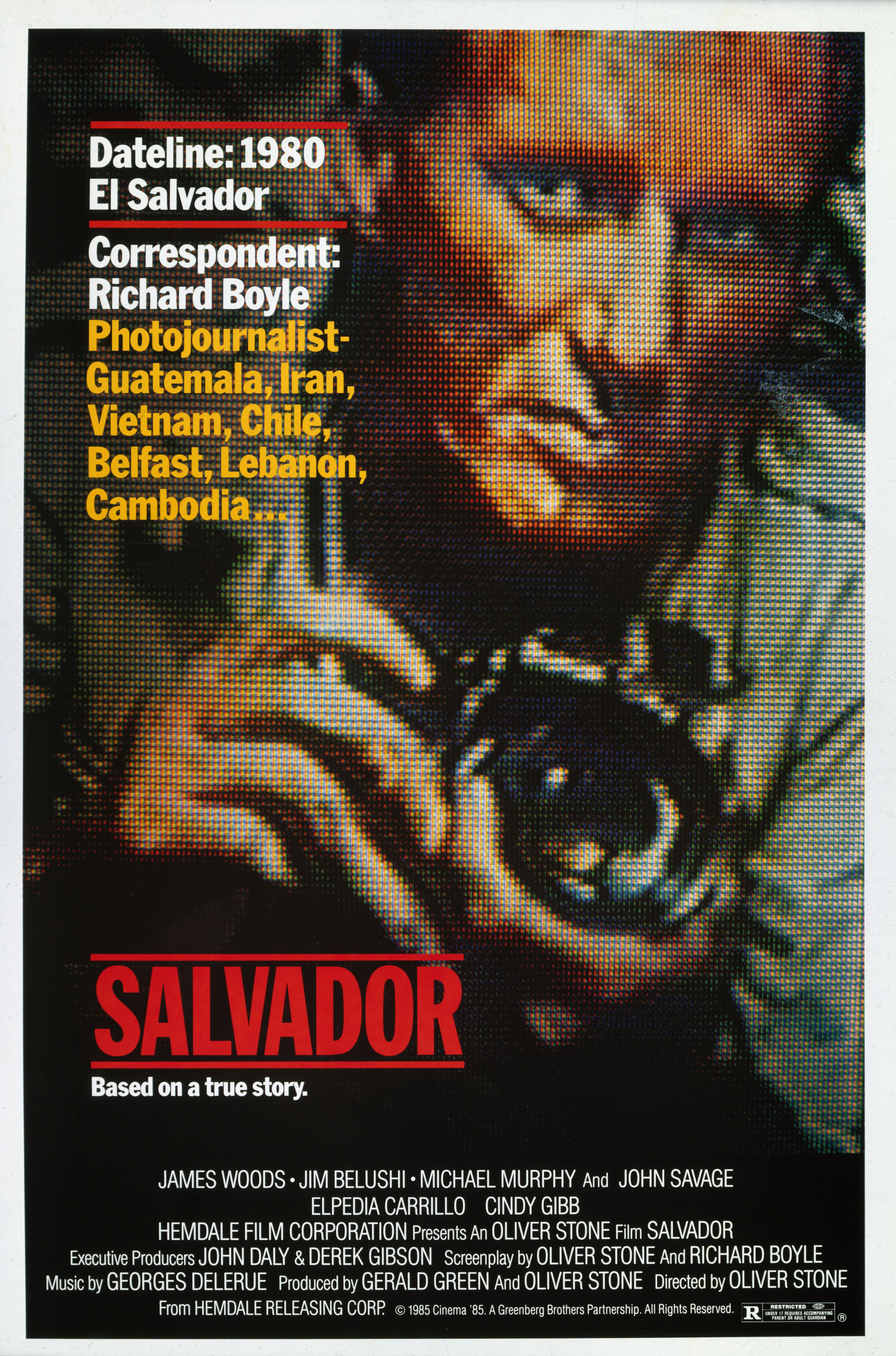

Oliver Stone’s Salvador is the only outright flop, nearly going straight to video until Stone’s follow-up Platoon made him a celebrated auteur. And it’s easy to see why they had misgivings about what Stone had wrought here. Based on another real-life war correspondent, Richard Boyle, the movie goes for a pulpier approach, paced as a mad dash into the middle of El Salvador’s civil war.

Boyle is fashioned as a Hunter S. Thompson-style muckraker and played by James Woods, in the actor’s greatest performance, that milks his rodent-faced intelligence and coke-fueled energy into a riveting character study. His sidekick is Dr. Rock, a radio DJ (James Belushi, well-cast as a useless slouch) and the two of them run off to Central America in the hopes of making some quick cash by covering the unrest.

Salvador is Stone’s first classic and ranks ahead of plenty of his more stylistically ambitious pictures. Woods’ degenerate fumbles about, eventually piecing together the fact that Americans are funding atrocities in El Salvador, since they’re perpetrated on the communist rebels, in this case, a group known as the FMLN. It revels in the depiction of Americans as bullies, naïve morons, and ineffectual bureaucrats, as they busy themselves destroying another small country to stop the Soviet menace.

As a decorated Vietnam vet, Stone had some first-hand demons to purge here against American interventions. He does so with great relish, as Woods’ ill-temper stops being a character flaw and more of a necessity to accurately cover the story when so many of his more respectable peers are eager to sell American bullshit.

Woods even takes a swipe at Schanberg’s Cambodia dispatches, touting that he never got to hide in a French embassy. It features the lost perspective that a degenerate can still have a functioning moral compass, as we now demand that everyone in public life have personal lives as spotless and well-arranged as Joan Crawford’s closets. And to be clear, that’s not a defense of anyone hiding dead bodies or real crimes.

Thankfully, Stone is too sophisticated a filmmaker to reduce this to a redemption story for Woods’ character. Instead, he introduces a truly noble combat photographer, played by John Savage, that pricks Woods’ conscience to do more, but we never forget this guy was always more devoted to the drugs and prostitutes on his beat. He improvised one of the highlights of the movie, a scene in a confessional booth where Woods admits he’s actually beyond redemption.

Salvador stands out here as the only picture of these that values the truth for its own sake. It may loathe the Americans and the dictator they fund, but it also dramatizes how quickly the FMLN resorts to the same atrocities given the chance. It’s a canny look at the dangers of any civil war, and still leaves the worst of the bill on America’s doorstep. Michael Murphy reappears here as a hapless American ambassador, too concerned with appearances to be truly effective, as he’s easily bullied by right-wing nutbags, emboldened by Reagan to take the gloves off, as if the country ever wore any.

And more than any of these other pictures, it works as its own effective piece of war correspondence. It highlights American culpability but doesn’t end with a pat rescue or last-minute save, or pretend that the locals are faceless, innocent bystanders. And its ending resonates with a particularly salty refrain right now as the US Border Patrol delivers the final atrocity.

Salvador was never going to be a hit, and it was the last of this little subgenre. The end of the Cold War would make countries like Indonesia, Cambodia, El Salvador, and Nicaragua irrelevant to American audiences, except as sneaker factories or sources of horror stories to make centrists pout over Sunday brunch. American media would use the supposed “end of history” of the 90s to shift its focus to domestic tabloid spectacles, which Stone would end up satirizing with his trademark excess in Natural Born Killers.

The reality is that it’s quite hard to make movies about journalists, a fact we forget because many of us still buy into a particular myth about the profession, one that began by fundamentally misunderstanding what Woodward and Bernstein did. Their Watergate reporting didn’t take down President Nixon all alone. A Congressional investigation was underway that also dug up little tidbits, including one about a secret recording system in the White House. What made this so notable is not that a pair of reporters dug up the truth, but that those in power did something about it.

Gibson’s reporting had zero impact on the coup in Indonesia. Waterson couldn’t stop the bombing or even save his pal. And El Salvador remained a basket case despite Woods’ efforts. Nolte and Cassidy made a difference, but only after they turned into a propaganda arm of the Sandinistas, by saying exactly what the rebels needed.

The Fourth Estate won’t advertise this, but it doesn’t matter much if the other estates ignore them. It’s why for all the news that modern audiences consume, so little of it seems to change anything. Journalism can be powerful, but only if it’s understood as the first of a three-step process. If they tell the truth, someone has to listen, and someone has to do something about it.

Otherwise, the truth is little more than another story to pass the time.