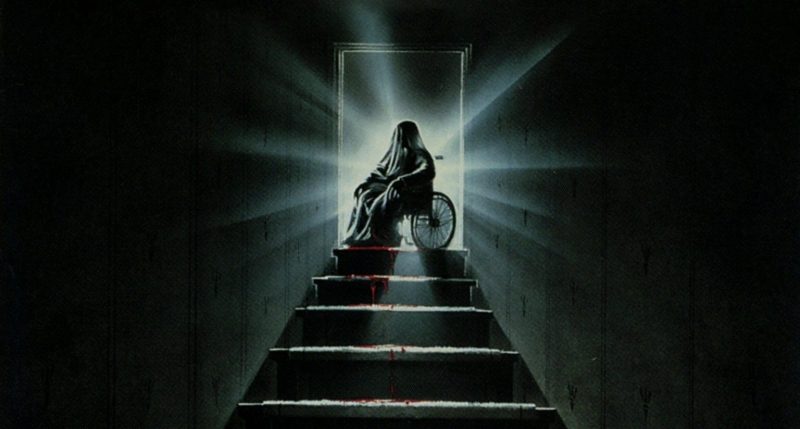

Michael Myers returns to Haddonfield after a seven-year hiatus

The word Return has appeared in the title of countless sequels, but rarely has it been more anticipated than for 1988’s Halloween IV: The Return of Michael Myers. When you think of horror’s most indomitable villains, the iconic ‘Shape’ is one of the first who leaps to mind, a character who was responsible for a whole decade of sleazy, Sean Cunningham style clones that crudely generecised the soon to be ubiquitous slasher. 1978’s Halloween may not be the first slasher, (Psycho, Peeping Tom, Torso, Twitch of the Death Nerve, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and Black Christmas can all stake a claim to varying degrees), but it was certainly the one to modernise the sub-genre for mainstream audiences, raking in an astonishing $70,000,000 worldwide ($157,986,179 when adjusted for inflation). This would inspire what would become known as the slasher’s golden age, a six-year deluge of stalk-and-slash infamy that put many independent filmmakers on the map.

It is somewhat strange that Michael was absent for such a large chunk of a decade that he was so instrumental to. Thanks to the wildly successful Friday the 13th, the slasher was at its overabundant peak back in 1981, and with Paramount set to bring Jason Voorhees back from the dead with future Halloween: H20 director Steve Miner’s Friday the 13th Part II, John Carpenter, who never wanted a sequel to the original Halloween, finally bit the bullet and bowed to indie producer Irwin Yablans, the two ultimately delivering a direct continuation of the first movie that was set on the same fictional night. Working with long-time business partner Debra Hill, first-time director Rick Rosenthal and Halloween cinematographer Dean Cundey, Carpenter went some way to capturing the original’s stifling mood, but the slasher had grown in Michael’s absence, as had slasher audiences.

Carpenter’s bare bones Halloween, a patient exercise in foreboding that kept our killer largely in the dark with its masterful use of space and shadows, arguably remains the pinnacle of the sub-genre, but by 1981 blood and guts horror was on everyone’s menu, practical effects maestros such as Tom Savini taking onscreen murder to new and excruciating places. The very real tale of an escaped mental patient stalking a generation of teenage suburbanites may have felt fresh in 1978, but by ’81 it had been imitated to derisory levels, August’s Student Bodies giving the already waning sub-genre the spoof treatment. The slasher as Carpenter had imagined it had become passe. All horror fans cared about was who-can-top-this bloodbaths, a formula that the filmmaker would look to tap into in spite of himself.

Carpenter loathed the final product, seemingly killing off both Michael and Dr. Samuel Loomis in the closing moments of Halloween II, thereby ending the chance of another direct sequel. The franchise still had legs at a time when the home video boom had taken horror to new commercial heights, but Carpenter and Hill had no intention of bringing Myers back from the dead. A compromise came in the form of 1982‘s Halloween III: Season of the Witch, a movie promoted under the Halloween marquee that didn’t feature Michael Myers at all. The plan was to release a series of films under the guise of the original franchise. Each would have a new story and cast of characters, allowing Carpenter’s most iconic creation to slip quietly into the shadows in favour of a different yearly ritual, but after a lacklustre response from audiences the idea was immediately shelved. The Halloween franchise, in any form, was seemingly put out to pasture.

You’re talking about him as if he were a human being. That part of him died years ago.

Dr. Loomis

In Michael’s absence, other slasher icons stepped up to the plate, Cunningham’s Jason Voorhees and Wes Craven’s genre-reviving Fred Krueger leading the way. By 1988, Freddy was the new commercial king, A Nightmare on Elm Street 4: The Dream Master raking in a cool $49,400,000 domestically. With Friday the 13th Part VII: The New Blood posting the poorest returns to date that same year, Jason was already on the wane after an incredible six appearances in seven years, but it was he who had stolen Michael’s spotlight more directly with his like-for-like appearance and brutal seek-and-destroy tendencies. While Michael had faded into genre obscurity, Paramount had accumulated a whopping $151,900,000 on Jason’s watch, with another instalment already in the pipeline. With the Friday franchise finally floundering, the timing had never been better for Michael to re-stake a claim, but the character was nowhere to be found.

Despite Carpenter’s past reservations, money talks and evil walks, and behind the scenes Michael’s return was well and truly underway. Syrian-American producer Moustapha Akkad had been pushing for a continuation of the Michael saga ever since the Halloween spin-off movies were nipped in the bud. In 1986, Carpenter was approached by B-movie distribution juggernaut Cannon Films, fresh off the release of Tobe Hooper’s enigmatic The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, to write and direct Halloween 4. The project was passed on to the late screenwriter Dennis Etchison, whose “cerebral” screenplay was rejected outright. Akkad, who had acquired the rights from Carpenter, had no interest in making a film with any substance, favouring a textbook slasher in the Jason Voorhees mode and upping the kill count considerably (19 compared to Halloween II‘s already excessive 11). In the ultimate irony, Myers was charged with imitating his most famous imitator.

Etchison, a writer who had already penned the novelisations of The Fog and the first two Halloween sequels, was thrilled to finally be involved in the cinematic side of things. In his version of Halloween 4, Halloween is banned in Haddonfield and no longer a recognised holiday. “The whole idea was repression versus acknowledging the bad things in the world,” he would explain in a 2017 interview with Blumhouse. Hours after picking up the final retyping of his screenplay, Etchison would receive a rather blunt and unexpected phone call from Hill, in which she informed him, “I just wanted to tell you, John and I have sold our interest in the Halloween franchise and unfortunately your script was not part of the deal.”

It was a devastating blow for a then 44-year-old Etchison, but he wasn’t bitter, later allaying fans’ fears by absolving the legendary director of any blame. “He’s the last honest man,” he would say of Carpenter. “A straight arrow. I’ve seen him a few times over the years since, and I did an interview with him that was published, and he is the best guy I’ve ever known and worked with in Hollywood. He is 100% honest, loyal and true. He doesn’t lie. He doesn’t cheat people. His goal is to make good films.”

It is something of a tragedy that Halloween 4 could and should have been a very different movie. The original screenplay, of which there were three drafts, was centred on a now teenage Tommy and Lindsey, whose babysitting nightmare a decade prior proved key to Michael’s bogeyman status. The fact that Tommy was the only Haddonfield resident who was willing to believe in the town’s omnipotent scourge until it was too late made for an interesting character going forward, particularly when you consider the psychological damage inflicted. He was the logical choice to take up the mantle in the absence of Jamie Lee Curtis, then branching out in an attempt to shake her scream queen stigma and the whole sister angle developed for Halloween II.

The premise of Etchison’s second draft, available online, showed immense promise, and could easily be seen as a commentary on horror movie censorship, which had applied a political tourniquet to the bloody extravagances of practical effects horror by the end of the 1980s, forcing directors to either embrace a more self-aware approach or prepare for the worst. In Etchison’s script, the residents of Haddonfield are suffering under a cloud of suppression, anything even remotely Halloween-related, including horror movies, forbidden outright. This leads to conflict between suffering businesses and terrified townsfolk pushing for even stricter laws. The script also teases Michael as a misunderstood character, a simple child plunged into a state of shock after his horrific deed on Halloween night, 1963. Ultimately, a rebellion against the town’s overbearing rules, which are seen as having a damaging effect on the community, leads to the return of Myers and a good-on-the-page drive-in theatre showdown. Interestingly, many of the screenplay’s kills are committed off screen.

The task of developing a script that was more suited to Akkad’s needs fell to Alan B. McElroy, who was given just eleven days to come up with a story, pitch it to executives and complete a final draft, a daunting prospect for a debut screenwriter. This was due to the 1988 Writers Guild of America strike, which at 153 days remains the longest strike in the Guild’s history, having a severe impact on many films, including the aforementioned fourth instalment of the A Nightmare on Elm Street series. McElroy came up with the idea of introducing another Myers relative in Brittany “Britti” Lloyd, the orphaned child of Laurie Strode, now living with the Carruthers family (the character’s name was later changed to Jamie as a homage to the absent Curtis, who was busy working on the Oscar-winning comedy A Fish Called Wanda). Their 17-year-old daughter, Rachel (Ellie Cornell) would assume the role of final girl in what was a more direct re-tread of previous Myers-led instalments. I know the character has her fans, who were outraged at her fickle offing in the early stages of Halloween 5: The Revenge of Michael Myers a year later, but I’ve never understood the attraction. She’s capable but hardly memorable. I wasn’t especially enthused by her return.

The version of Halloween 4 that was released in theatres would undergo further changes, mainly due to budget issues, and it shows in what proves something of a damp squib action-wise. A scene involving a giant fire that burned down Sheriff Meeker’s house was scrapped entirely, which led director Dwight H. Little to focus on a flimsy love triangle involving Rachel, douchebag squeeze Brady (Sasha Jenson), and unconscionable harlot Kelly, the daughter of Meeker, which does little to improve on the movie’s story, proving more of a distraction than anything. At times it feels like a Beverly Hills 90210 special with a serial killer subplot.

The plot itself is as thin as any stalk-and-slash fodder, with little-to-no attempt at making Michael’s long-awaited return a memorable one. In a rather remarkable stroke of coincidence, the authorities have scheduled a patient transfer almost ten years to the day of the original Haddonfield massacre, which gives Myers plenty of room to emerge from a decade-long coma and plan his latest onslaught. His sudden recovery is triggered by talk of the killer’s niece, which leads to a mini ambulance massacre that likely could have been prevented if those in charge had taken the time to restrain the most notorious serial killer in recent memory. Will they ever learn?

I have written about the problems intrinsic to sequels, especially those in the horror genre that go for a direct continuation, and Halloween 4: The Return of Michael Myers certainly falls into that category. When dealing with the same characters in similar situations over and over, it is only inevitable that those characters will repeat past mistakes, their integrity jeopardised for the sake of narrative convenience. Why risk moving Myers without the aid of armed police and handcuffs? In fact, why move him at all, especially considering the time of year? You’re just asking for it in the worst way imaginable. Of course, if those characters learned from their mistakes and actually applied a bit of logic to the situation most slashers would be over by the end of the first act, this one even sooner.

Th same can be said of Michael’s nemesis. The character who suffers most from Halloween 4‘s lacklustre, commercially clinical approach is the most interesting in the whole movie: Dr. Samuel Loomis. The problem with returning to the same scenario is that it all becomes jarringly formulaic. You just can’t engage with these characters like you once did. The original movie was simple and sparse, its subject unexplored in a way that implored fascination, which made Loomis’ ominous forewarnings, channeling the Hitchcockian harbinger of death trope, more impactful. For the character’s third appearance very little has changed, the actor’s once-iconic turn beginning to smack of self-parody. There’s only so many times you can swallow the same old spiel before it all becomes just a little silly. Once was enough, twice was a push, but three times is shaky territory in terms of credibility. Pleasence is typically watchable, but the paint-by-numbers script smacks of lethargy to the point that, when healthcare corporate complain about his thespian ravings, you kind of empathise with them. Loomis does grow in one sense, becoming a John McClane style action hero who crashes through windows and leaps fifty feet through the air to avoid gas station explosions, shades of the director’s action movie background, but some characters carry a prestige that makes them an ill fit for that kind of thing.

To be fair to Little and cinematographer Peter Lyons Collister, Halloween 4 opens rather beautifully, capturing the rustic, autumnal aesthetic of the original movie in a way that is genuinely spooky and hugely promising. There are some truly ominous establishing shots that capture that familiar Haddonfield mood, images emboldened by that iconic Halloween text, Carpenter collaborator Alan Howarth providing a subtle variation of the Halloween theme that reverts back to the original composition where necessary. The opening moments really impressed me, but as soon as Michael escapes, the film descends into bog-standard slasher territory. 20th century slashers were not renown for their skill and subtlety. They were brainless platforms for practical effects slaughter, which is basically why we love them, but this isn’t any old masked killer; nor is it Jason Voorhees, a character who has always been unashamedly trashy and therefore gets a pass. With Michael I expect a little more. Along with Leatherface, he’s the original marquee stalker, the slasher villain by which all future villains are judged. He deserves better than to be lumped in with the rest, but for the most part that is the case here, and as can be deduced from the movie’s commercially safe development, intentionally so.

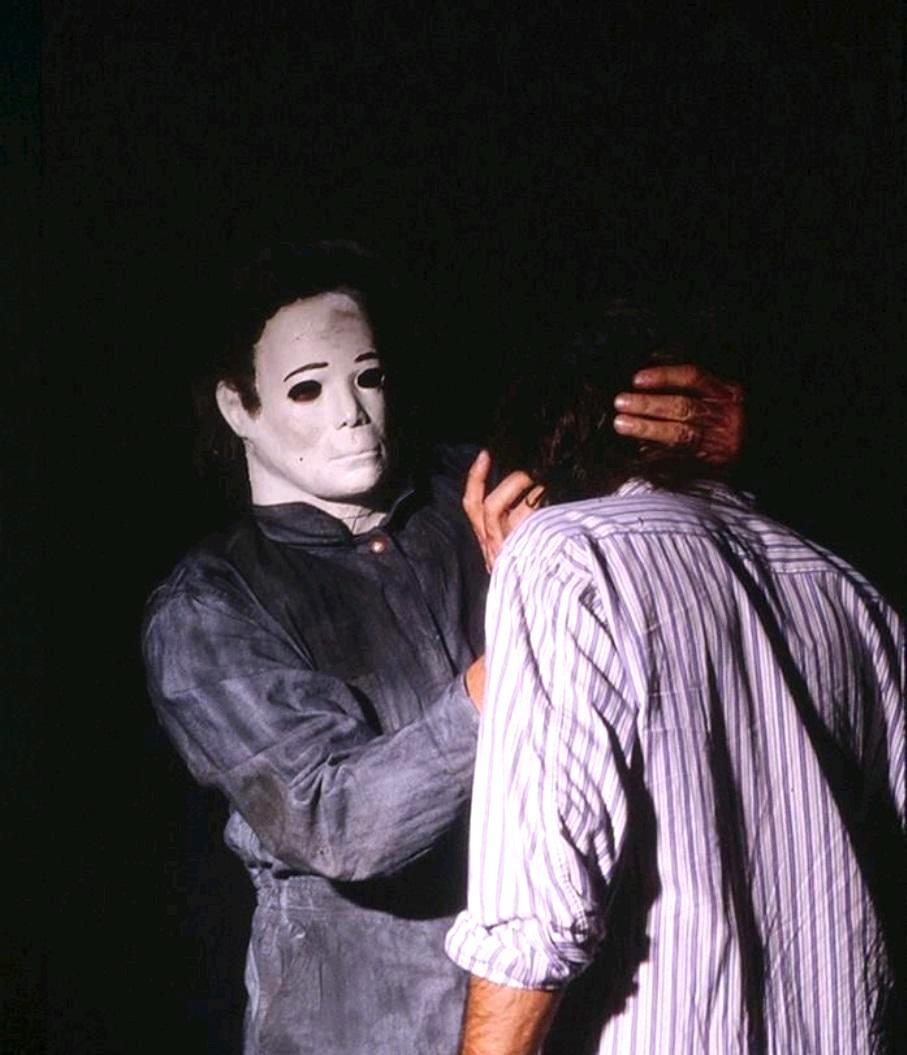

Make no mistake about it, Voorhees is the inspiration for Michael here. The beauty of the original Myers was his supernatural air. It wasn’t obvious, but he gave that impression. When he fled the scene of the original Halloween massacre having been shot several times by Loomis, it seemed incredible but plausible. There was a chance that Loomis could have missed every vital organ; those once in a lifetime miracles are rare, but they do happen. By Halloween 4 he is treading super invincibility levels. When Michael is confronted head-on by generic heartthrob Brady, the kid’s attacks have absolutely no effect. Myers just stands there like a monster pro wrestling heel shrugging off strikes from a disbelieving babyface. The townsfolk, led by a rabble of shotgun-wielding hillbillies, do eventually manage to put him down, but in a needlessly hyperbolic scene that again belongs in an action movie, Michael eating enough artillery to sink a U-boat before finally plummeting down an abandoned mine shaft, and that’s after being mowed down by a pick-up truck travelling at full speed. Recent reboots have followed the same path, so an indestructible Myers is more accepted, becoming the norm for a character with a seemingly endless commerical lifespan, but it wasn’t always that way. Halloween 4 was the point of no return.

In 1988, it was strange to see the character who most inspired the cynical slashers of old take part in one. Halloween II did the same to a degree, but thanks in large part to Cundey’s involvement and the fact that Carpenter re-shot some of those scenes, it still felt like a Halloween movie beyond its bloody commercial liberties. Beyond those opening moments there’s very little to establish Halloween 4 as a film belonging to a unique franchise. It meanders too. We don’t see much of Michael for large stretches, and not in a less is more way. It doesn’t tease his presence effectively enough or attempt to establish his quiet omnipotence. He doesn’t have that grim, cock-headed inquisitiveness, that aura of a child who never grew up but was never really a child to begin with. He’s not there and then he is, popping up for the occasional kill. Even the mask is a bad representation of the evil lurking beneath, the gaunt inhumanity of the original replaced with something resembling a cute smile. McElroy’s screenplay ditched the supernatural element, presenting Michael as a literal escaped mental patient. As a result he has lost his sense of otherworldly mystique.

For a production that sets out to deliver a more generic slasher in the Voorhees mode, it’s all a little bloodless too. One of the reasons why the popularity of the Friday the 13th series was on the wane was censorship, at the hands of both the Motion Picture Association of America and Paramount themselves, who were openly ashamed of the series to the extent that they became self-censoring to a degree. Not only did Halloween 4 revert to generic slasher convention, it did so during the genre’s censor-imposed decline. In terms of violence, the movie is on a par with 1989‘s Jason Takes Manhattan, a film that put the Friday the 13th franchise down for a nine count. Asides from a fairly brutal throat-ripping, there’s very little gore on show. Even when Michael embarks on a mini, truck-bound killing spree, the kills are largely off-screen or implied. As the original Halloween proved, gore isn’t everything, but when you set out to make a textbook slasher it kind of is, and Halloween 4 lacks the suspense and technical inspiration to be anything more. Ultimately, it falls into a kind of creative grey area.

Ten years ago, he tried to kill Laurie Strode. Now he wants her daughter.

Dr. Loomis

Don’t get me wrong, I love generic slashers. To me they’re fast food entertainment. You know exactly what you’re getting, you know exactly how they taste, and there’s every chance you’ll be scraping the gristle from between your teeth for long stretches, but they are strangely compulsive viewing. You realise that your time might be better served watching something with a little more depth, but sometimes you just have to switch off and embrace the silliness. Halloween 4 isn’t silly or cheap enough to pull off that kind of experience. It has a more developed screenplay than most slashers, better actors, better direction, and it continues to capture the Halloween mood and aesthetic at times, with some cute instances of foreshadowing that build towards a stunning revelation, but it can also be very predictable and throwaway. At heart it is modelled on those inferior rip-offs that Halloween directly inspired, and it cheapens affairs, there’s no getting past it.

Halloween 4 does have an excellent twist, so if you’re yet to see it I suggest you stop reading now. There are moments in the movie that hint at a connection between Michael and his young niece, something Little had developed himself through his interpretation of Etchison’s script. Jamie even runs into her uncle at the Haddonfield fancy dress store, picking out a costume that is almost identical to the one worn by a young Michael on the night that altered the course of his life, and horror movies, forever. When we finally see Jamie covered in her foster mother’s blood and brandishing a butcher’s knife, it is absolutely startling, an unexpected jolt that releases you from narrative complacency, offering fresh hope for a sequel that would stray from the original story and presumably avoid the same level of repetition that is intrinsic to a more direct sequel.

The original idea was to have Jamie become a killer in the Myers mode — again, something Friday the 13th had almost pursued with Tommy Jarvis — but as was the case with Friday the 13th Part V: A New Beginning, the concept was ultimately nixed, this time in favour of a psychic connection angle that maintained Jamie’s heroine status and led the series along an increasingly unstable path. The reasons for such an unexpected pivot were simple: producers believed that shelving or even relegating the universally recognisable ‘Shape’ would hurt the financial potential of the franchise. They had learnt their lesson with Halloween III: Season of the Witch, an interesting, yet fruitless digression that put the series in limbo. It would have been great to see how the franchise would have panned out with Jamie taking the homicidal reins, but would it have appealed to a broader audience? Could such a spin-off really have had legs going forward? Frankly, we’ll never know, but with the Myers-led franchise still going strong well into the 21st century, it is difficult to argue with the logic. Like Dracula, Frankenstein’s monster, and those other great icons of the genre, Michael will always be a mainstream draw. It’s a formula you just don’t mess with.

Director: Dwight H. Little

Screenplay: Alan B. McElroy

Music: Alan Howarth

Cinematography: Peter Lyons Collister

Editing: Curtiss Clayton