Rob Bottin delivers monster movie magic in what is arguably John Carpenter’s finest achievement

John Carpenter is the ultimate example of an indie filmmaker. His best movies are typically humble productions which rely on creativity, resourcefulness and ingenuity rather than big bucks extravaganza. On the rare occasions he has been backed by the major studios, he’s seemed rather less comfortable. If you look at the director’s most expensive movies, they’re generally footnotes in his career, creative missteps that failed to communicate with audiences. Films such as the Warner Brothers backed Memoirs of an Invisible Man floundered on just about every level; all the ingredients were there for a sure-fire hit, it just didn’t pan out that way.

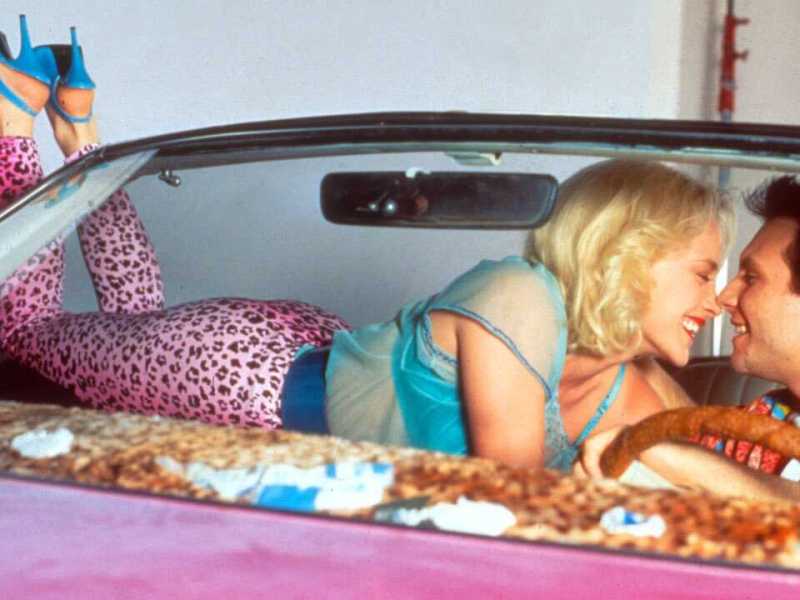

Perhaps the biggest indicator that Carpenter is less effective working with big budgets is his most expensive film to date. 1996‘s Escape from L.A., a belated follow-up to the filmmaker’s dystopian classic Escape from New York, was a commercial disaster, bringing in little more than half of the $50,000,000 shelled out. I remember how excited I was when news of the sequel first reached me. I was thirteen and still naïve enough to assume that newer meant better. The trailers only strengthened those assumptions. The film featured a number of interesting concepts and classic Snake moments that a deftly edited trailer beautifully teased, but the actual film felt bloated and mismanaged, as if it had been conceived by a kid with too many toys at their disposal. There was also a fifteen-year gap between the two films following a protracted development period that went all the way back to 1987. This gave the casual moviegoer plenty of time to forget about Kurt Russell’s iconic, gravel-voiced antihero.

A list of Carpenter’s most renown movies tells an entirely different tale. 1976‘s racially unifying urban western Assault on Precinct 13 is a prime example of the filmmaker’s bargain-basement artistry. The movie takes a basic premise, a paper-thin cast of low-key actors, all of it sprinkled with the director/writer/composer’s inimitable synth stardust, Carpenter delivering a stone cold classic of sociopolitical resonance that slips comfortably into the realms of genre cinema. The fact that it made $11,748, roughly a tenth of its cost, was neither here nor there. Carpenter had made a movie, and a damn fine one at that.

In 1978, Carpenter would dust himself off to bring us one of the most profitable independent movies ever made in slasher innovator Halloween, a film that would spawn a decades-long franchise and a whole host of sleazy Friday the 13th styled imitators. So low on funds were Carpenter and long-time associate Debra Hill that cast members were asked to provide their own wardrobes. Even Michael’s iconic visage had a huge element of luck to it, future Halloween: Season of the Witch director and long-time Carpenter collaborator Tommy Lee Wallace finally cutting the eyes out of a William Shatner mask and painting it white after a plethora of designs had left much to be desired. Halloween would manage an incredible worldwide box office gross of $70,000,000. Quite the payday for a director who, “just wanted to make a film”.

It was after Halloween II, a venture that brought in ten times its $2,500,000 budget, that Carpenter set to work on his first major studio movie: 1982‘s The Thing. Ironically, it was Michael Myers’ second outing, a film that Carpenter initially wanted no part of, that paved the way stylistically. Carpenter always felt that less was more with a character who relied so heavily on mystique, manipulating space and shadows in a way that played tricks with the imagination, but by 1981 the original Halloween was looking pretty tame in the eyes of a generation baying for the crude practical effects artistry of the now ubiquitous slasher. In the space of three years, the innovative filmmaker had been reduced to imitating a sub-genre that he had largely inspired.

After handing directorial duties over to rookie filmmaker Rick Rosenthal, Carpenter would write, produce, and compose the score for Halloween II, even re-shooting several scenes after being unhappy with a film he would later describe as “an abomination,” and “a horrible movie“, but something had become clear. Thanks to major advancements in the field, practical effects were the future. When it came to horror, modern audiences had had their fill with filling in the blanks because what was onscreen was now rivalling their imaginations. That same year, John Landis’ groundbreaking offbeat horror An American Werewolf in London would win the first ever Academy Award for Best Makeup, and Carpenter had landed just the property to forge a visual extravaganza of his own.

I dunno what the hell’s in there, but it’s weird and pissed off, whatever it is.

Clark

It’s amazing to think that, technically speaking, Carpenter’s film falls into the remake category. In an era of countless prequels, sequels and reboots, we have come to regard the whole process as a cynical exercise whose primary goal is to slash marketing expenditure. It is facile to write off every remake as a lazy cash-in, but there’s so much underhanded trash to sift through in the 21st century that we’ve all become just a little jaded, the emergence of CGI proving as much a hindrance as it is a blessing in the hands of the corporate powers that be. It seems that every property that was even remotely popular during the 1980s has been given the makeover treatment, lame ducks such as 2010’s A Nightmare on Elm Street offering unimaginative CG upgrades on practical effects that were far superior visually. Thanks to the incessant evolution of modern computer technology, those effects have already dated horribly, which leaves little else to admire beyond box office returns. Conversely, the best practical effects artists are like hands-on magicians. Almost forty years after The Thing‘s initial release, there are still moments when you stop and think to yourself, ‘How in the hell did they do that?’

Audiences and critics didn’t take to Carpenter’s The Thing, a movie that Mexican filmmaker Guillermo del Toro would later describe as the “Holy Grail”. Part of this was no doubt due to their allegiance with Christian Nyby’s Cold War, alien invasion vehicle The Thing From Another World, the first adaptation of John W. Campbell’s 1938 sci-fi novella Who Goes There?. It didn’t help that Carpenter’s remake happened to coincide with the release of two of cinema’s most groundbreaking sci-fi epics in Steven Spielberg’s ‘kids in peril’ classic E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial and Ridley Scott’s visual colossus Blade Runner, each blessed with the kind of iconic score that put Morricone’s work on The Thing firmly in the shade. That’s not to discredit one of cinema’s greatest composers, who delivers a minimalist, downbeat classic of devastating potency, but Blade Runner is arguably Vangelis’ finest achievement, and John Williams’ E.T. score would define a generation. It was simply a case of bad timing.

There was also the generational element to consider. Younger moviegoers may have been craving gore and other grotesque fancies, but a good percentage of mature audiences viewed them as tasteless. Whether it is Dr Jekyll’s iconic 1931 transformation, an effect achieved using different coloured filters and makeup, Boris Karloff’s Frankenstein or H.R. Giger’s phallic parasite the xenomorph, moviegoers will always stick to what they know, and there’s generally a degree of bias involved. As brilliant as the movie is, something the consensus has come to accept all these years later, The Thing‘s main drawing point back in 1982 was its practical effects, which would have been just as astonishing, and potentially off-putting, to moviegoers in the early 80s as CGI is today, but Carpenter, himself a huge fan of Nyby’s original (there’s even a visual reference to the movie in Halloween), was worried that he wouldn’t be able to do it justice without the aid of such technological advancements, which allowed him to stay truer to the literary source material. In order to achieve the desired effects, Carpenter hired 22-year-old prodigy Rob Bottin, a precocious talent he had previously worked with on The Fog who already had seven productions under his belt.

The alien effects that Bottin and his crew brought to the screen were breathtakingly audacious, the film’s polymorphous entity assuming all kinds of forms in its quest to consume every living thing that it comes into contact with. Particularly impressive is a version of the creature that has become known as ‘Blair-Thing’, a towering mass of tumorous flesh formed from a mishmash or past victims. There’s even a scene to rival Alien‘s iconic chest-burster when Dr. Copper’s arms plunge into Norris’s opening torso, the creature’s modified form tearing off his limbs with its enormous, abstract teeth. Just as disconcerting is ‘Norris-Thing’ or ‘Head Spider’, an inverted, arachnid-like creature with eyestalks sprouting from beneath a vaguely-human head. The film’s eponymous parasite is absolutely monstrous, a biological eyesore that taps into claustrophobic bodily fears, the kind that would influence such modern classics as Richard Stanley’s Color out of Space.

The Thing‘s development began as far back as the mid-1970s, with several writers and directors attached to the project at one time or another, including The Texas Chainsaw Massacre‘s Tobe Hooper, the consensus being that the film had to be bigger, but it was the son of screen veteran Burt Lancaster, Bill, who finally landed the gig after proposing a more claustrophobic movie that tapped into audience paranoia. Initially, The Thing followed the tried-and-tested formula of keeping the alien creature largely hidden, something closer to the way Carpenter had presented Michael Myers a half-decade earlier, but it was Bottin who put him on the right path, leading the writer along creative avenues that saw him come up with arguably the film’s most suspenseful scene: a hyper-tense stand-off that forces our crew into a blood test that will reveal the monster’s true identity. So important was that particular scene that it helped convince Carpenter to finally take on the project.

When Bottin joined up with Carpenter and co, pre-production was already underway. Designs for the shapeshifting creature were yet to be thought-up, but Carpenter wasn’t too pleased with Bottin’s initial ideas, finding them a little on the peculiar side. When collaborator Dale Kuipers was forced to leave production for personal reasons, it was suggested that Bottin, who’d just finished working as an assistant to Rick Baker on metamorphic werewolf horror The Howling, collaborate with comic book artist Mike Ploog, someone whose work he was already a big fan of. Since the film’s titular monster had presumably travelled the universe to wind up near the cast’s doomed outpost, it was deemed logical that the creature would retain some of the physical attributes of other alien hosts. Finally, things were beginning to take shape, both figuratively and literally.

You see, what we’re talkin’ about here is an organism that imitates other life-forms, and it imitates ’em perfectly. When this thing attacked our dogs it tried to digest them… absorb them, and in the process shape its own cells to imitate them.

Dr. Blair

As Bottin would explain in an interview with Fangoria, “When I described my ideas to [Ploog] he dropped his coffee cup. But what he came up with was great. We must have gone through a thousand drawings — all good stuff. There was enough for six more movies.” Owing to its transformative nature, the monster’s design was actually several, a confusion of assimilated subjects melding into a single, shape-shifting grotesquery. “I didn’t want it to remind anyone of any monster they had ever seen,” Bottin continued. “I wanted to avoid, if possible, all the clichés. It was a dream come true. We could do anything; just think things up and make them.”

Carpenter, still reeling after an abundance of Halloween imitators had turned his movie into a cliché, also made a conscious effort to steer clear of horror convention, removing a series of classic horror beats from Burt Lancaster’s original script. “At that particular time I had unleashed this terrible thing about horror movies with Halloween,” Carpenter would explain. “All these imitators came out and threw every possible cliché up onto the screen—the body in the closet, the thing behind the door, all of that stuff. I suppose I was trying to get away from that and make this film better.”

Achieving the creature’s unique aesthetic was excruciatingly hard work, so hard that Bottin, who has become something of a recluse in recent years, struggled under the pressure of the film’s large-scale production, even bringing in fellow special effects legend Stan Winston to lighten the crew’s burden. Winston was responsible for the infamous scene with the shape-shifting dog, which is near the beginning of the movie and helped to influence the tone of what would follow, though Winston was so impressed with Bottin’s work that he refused to be credited. “I found it difficult to work with so many people,” Bottin would lament, “all with different needs and wants… It got to the point where I was thinking, ‘If I have to do another stinking mechanical dog, I’ll go nuts. So, I asked John if we could use Stan…What was interesting was that it was kind of like being a director and hiring an effects guy for my own movie. I told Stan what I had in mind, and just let him go. I didn’t even go over to his shop. I’d told him to call me when he was done; and when I saw it, I was blown away! I mean, he walks in with this outrageous dog-monster on his arm, and I just loved it!”

It was a startling approach that horrified audiences to the point of distaste, but not everything is so in your face. In fact, the movie is driven as much by the subtleties and slow-burning tension of those early scenes: the invading husky which quietly stalks the outpost before erupting into a ferocious torrent of tentacles, the two-faced corpse dripping off the examination table in search of its next victim, the dead-eyed sheen of newly discovered hosts. The film’s opening scene, shot against a blizzard of desolate white, sees a Norwegian pilot, wielding a rifle and calling out in a panic, shot dead in an act of self-defence. Out of pity, Clark (Richard Masur) kennels his now-stray sled dog, unwittingly exposing the crew to a creature who shows incredible patience and cunning. It slowly becomes clear that this isn’t your average monster. It’s everywhere and nowhere. It is all-consuming.

While the 1951 film ditched the story’s xenomorphic alien for a parasite of the standard bloodsucking variety, the evolution of practical effects allowed Carpenter to present us with a creature that is able to assimilate other organisms on a cellular level. Carpenter’s titular monster is an entity of almost invincible proportions, a creature with the ability to divide and conquer with its adaptive powers and surreptitious nature, proving itself an organism of raw intellect with an uncanny knack for self-preservation. Not only can it imitate the appearance of any living being, it can adopt their personality and mannerisms, making it undetectable to even the keenest eye. This leads to one of the most intriguing open-ended twists in modern cinema, one that sees us questioning protagonist R.J. MacReady (Kurt Russell), until that moment the film’s undoubted hero, as the true incubator for one of cinema’s most devious creations. It’s a devastating twist of nihilistic proportions, perhaps another reason why audiences and critics were initially so cold towards The Thing.

Moviegoers, especially back then, weren’t so attuned to endings that were open to interpretation. Today they’re much more common, but something so bleak must have been a real gut-puncher as the US entered the MTV extravagance of the Reagan 80s. Post-Watergate paranoia movies such as Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation and Michael Small’s Marathon Man were already on the wane in 1982, America gearing-up for a period of Cold War triumphalism. By the mid-80s, audiences were flocking to see Rocky IV‘s eponymous pugilist lift the heavyweight championship at the expense of Dolph Lundgren’s poster boy for ethic cleansing, Ivan Drago. After so much dissension and distrust, Americans were more than ready to return to the realms of reassuring Hollywood fantasy, and The Thing is anything but.

“John Carpenter and I worked on the ending of that movie together a long time, “Russell would recall in an interview with The Huffington Post. “We were both bringing the audience right back to square one. At the end of the day, that was the position these people were in. They just didn’t know anything. They didn’t know if they knew who they were, but had you seen all the things in the movie, you’ve heard MacReady say, ‘I know I’m me,’ Well, you either believe him or you don’t. And Childs — you know, one of my favorite lines in the movie [is], ‘Where were you, Childs?’ And I think that basically says it all. I love that, over the years, that movie has gotten its due because people were able to get past the horrificness of the monster — because it was a horror movie — but to see what the movie was about, which was paranoia.”

Carpenter’s remake, despite increased political tensions during the 1980s, may not be as overtly Cold War driven as Nyby’s original, but the film’s relentless sense of paranoia drenches to the bone. Traditional horror utilises all kinds of tricks to ramp up the tension ― jump scares, Lewton buses, POV masking, villains that inhabit dark corners ― but all of that pales to a monster that doesn’t have to reveal itself, that could be sitting right next to you the whole time, steering your suspicions elsewhere with an organic savvy that is almost impenetrable. Once the outpost’s specialist Dr. Blair (Wilford Brimley) becomes aware of the creature’s unique abilities, he immediately reaches for his pistol. He may suspect that his colleagues are infected, but he can’t prove it, every little action becoming a reason for scepticism and distrust. Ultimately, ‘The Thing’ doesn’t have to lay a finger, an elongated limb or a spindly protrusion on anyone. Before long, its prey will wind up taking each other out from sheer uncertainty.

Watchin’ Norris in there gave me the idea that… maybe every part of him was a whole, every little piece was an individual animal with a built-in desire to protect its own life. Ya see, when a man bleeds, it’s just tissue, but blood from one of you Things won’t obey when it’s attacked. It’ll try and survive…

MacReady

Revealing too much can prove the death knell for horror movies, but for all of its visual embellishments, The Thing doesn’t sacrifice on suspense. Like many of the greats it plunges its characters into a hopeless environment of almost total isolation. Its remote location in the Antarctica makes our crew vulnerable to even the smallest hiccup, adding extreme weather conditions and limited supplies to their paranoia-induced battle with an unknown quantity. MacReady and his snow-bitten comrades have nowhere to turn and nobody to turn to, facing an alien entity in an alien land. It’s all so hopeless.

With this kind of set-up, the movie grabs you by the throat and never lets go, and there are so many classic scenes to cherish as the community continues to fall apart and infected crew members are picked off with the kind of inevitability that would further displease critics, who saw the movie as being too bereft of hope. It may have nihilistic tendencies, but that’s kind of the point given the cast’s situation, and the movie is never drab or wasteful, making the most of every last second. Revisiting The Thing, I struggled to think of another movie with such relentless and sublimely paced tension. In this regard, it was, and perhaps still is, unsurpassed in the Carpenter canon.

With The Thing, Carpenter once again failed to make any serious commercial waves, managing a rather paltry $19,600,00 on a budget of approximately $15,000,000, though like many iconic films of the era, it fared much better on VHS the following year, quickly achieving cult status among horror fans. While critics praised the film’s technical achievements, they slammed the amount of exposure given to Bottin’s monstrous creations (a mixture of chemicals, food products, rubber, and mechanical parts), as well as the movie’s nihilistic tone and what many perceived to be weak characterisation. As is the case with 21st century CGI, traditionalists felt the movie lacked substance, eschewing traditional storytelling elements for technological fancies. This was also an era of horror movie censorship, a legacy that Carpenter’s iconic slasher villain Michael Myers was directly responsible for, so The Thing‘s jaw-dropping visual elements were almost destined to rub naysayers the wrong way.

On the industry’s criticism of The Thing, Carpenter would say, “I’ve always thought that was somewhat unfair. I mean, the whole point of the monster is to be monstrous, to be repellent. That’s what makes you side with the human beings. I didn’t have a problem with that. The critics thought the movie was boring and didn’t allow for any hope. That was the part they really hammered on. The lack of hope is built into the story. There is an inevitability to it, but that’s not necessarily a negative.”

Years later, instead of writing the film off as a grotesque fancy, we’re instead asking the question: is The Thing Carpenter’s greatest ever achievement? That seems to be the consensus among fans, and in some ways it’s his most influential movie, one that not only matches the original but in many ways surpasses it, and how many reboots can you say that about? In fact, reboot has become such a dirty word that I’d rather describe it as a re-imagining, because visually The Thing has all the imagination in the world, and in many ways is just as resourceful as something like Halloween, a movie that relied on subtleties out of necessity. The Thing is classic Carpenter with a cinematic upgrade, a larger budget loosening the visual limitations that helped forge the director’s legendary resourcefulness, the kind that is still on display here. With The Thing, he gets the balance just right, staying loyal to those successful, once necessary subtleties of old, while bringing his latest monster out of the shadows and into the spotlight.

As Carpenter would explain in a 1999 interview with Creative Screenwriting, “Bill wrote the screenplay with the monster in the shadows, the old Hollywood cliché stuff, which everybody still talks about even to this day. Rob Bottin was the guy who said, “No, you’ve got to put him in the light, then the audience really goes nuts. They really go nuts because there it is in front of them.”

Director: John Carpenter

Screenplay: Bill Lancaster

Music: Ennio Morricone

Cinematography: Dean Cundey

Editing: Todd Ramsay

John Carpernter’s The THING remains one of my all-time favourite sci-fi horror films. From story, to cast, and of course the amazing practical SFX The THING is a masterpiece on so many levels. It’s one of those movies that you always seem to notice something new whenever you rewatch it. Wonderful to read your retrospective piece on this classic!

LikeLike

Thanks, Paul.

Wonderful that you took the time to read.

The Thing is timeless suspense wrapped in a still-mesmerising SFX package. It amazes me that it was so poorly received by critics at the time of its release. Thankfully, and deservedly, it now gets the universal plaudits it deserves.

Just a fantastic movie.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, its amazing to thing The THING was panned by critics at the time. As is often the case the film enjoyed a resurgence on VHS and DVD to become a classic – and rightly so. Carpenter is one of my favourite directors and his work always brings fresh ideas to the table. The THING gets everything right and no matter how many times I see it I’m on the edge of my seat watching it.

LikeLike

Me too. I could watch it forever. Carpenter is right up there for me too. His indie catalogue is incredible and his scores are mind-blowing and extremely influential.

Assault on Precinct 13, Halloween, The Fog, Christine, Escape from New York, The Thing, Big Trouble in Little China, They Live! What a run!!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for reviewing this. The Thing is an extraordinary film and one of my absolute faves. I was too young to see it at its cinema release, but boy did I catch up big time on VHS and later DVD. The visual effects are something to behold for its age, along with a fear and creepy-factor notched up to maximum, which works especially well in such a harsh setting as an Antarctica research base. Chilling and gruesome!

As an aside – I remember playing the PlayStation 2 official adaptation of the movie, and the game was just as terrifying and atmospheric 😱

LikeLike

My pleasure. Thanks for reading.

It’s everything you say; an astonishing movie with practical effects that still make you scratch your head and ask, ‘how did they do that?’

I remember that game! I remember enjoying it but I remember it being really difficult for some reason. I can’t remember why exactly but there was something that made it especially tough. Perhaps you remember? Maybe I was just terrible at it. 😁

LikeLiked by 1 person

Now I want to watch it again, for the umpteenth time! 😋

Re: the PS2 game, no, you weren’t terrible at it! It was really difficult I remember, and I never completed it – got about two-thirds through, and that was including using some online walkthroughs and hints. Gah!

I think what made it especially hard was trying to locate med-kits, then flamethrower fuel to defeat the Things… even something as innocent as a handheld blow torch was so hard to find in the game. Shotguns, rifles and other weapons seemed of limited use later on. That said, it was still a super intense and enjoyable game. Being stranded outside and seeing your health bar grind down to zero due to freezing weather and having to hide in a tool shed to warm up, then one of your comrades would either freak out in fear or turn into a Thing!

There was a nasty level in the barracks I remember, in the washroom facility, were there were splatter marks on the wall and bits of bodies everywhere. Eek!

LikeLiked by 1 person