Artistic disputes, creative paranoia and reflections on a posthuman world, VHS Revival explores one of sci-fi’s most enduring wonders

Blade Runner may lack the relentless action of some of cinema’s best-loved sci-fi hits, but what it has in abundance is beauty. There are many versions of the director’s 1982 classic, but for me the aptly titled ‘Final Cut’ is the most definitive, offering a much bleaker and authentic vision of a future where corporate moguls flaunt technological progress like self-aggrandising gods. The film’s 2019 vision of Los Angeles is a teeming metropolis of urban and environmental decay, a world in which bioengineered beings become slaves to that very progress, in which other, superior beings raise questions about a species that has been severely dehumanised. It is despairingly cold, bleak and emotionally barren, and yet it’s all so ravishing, a majestic feat of grandiose world building that shimmers like a galaxy with an ethical black hole burning deep at the heart of it. From the very first rumblings of Vangelis’s awe-inspiring ‘Main Titles’, you know you’re experiencing something truly monumental.

Blade Runner would shape and mould dystopian cinema for decades to come. It has its own influences, most notably Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (Scott and cinematographer Jordan Cronenweth even using Lang’s ‘Schüfftan Process’ to achieve the movie’s famous ‘shining eyes’ effect) but the film left an indelible mark on the collective imagination: the neon-drenched cityscapes, the juxtaposing dank of a society without hope, the colossal environmental stamp of misguided corporate ambition hammered home by the almost ceaseless acid rains; and, of course, its emphasis on mid-20th century noir aesthetics: the smoking figures, the long trench coats, Rachael’s classic 40s dame. Scott took those tropes and updated them for a post-human world, a stunning matrimony of old and new making Blade Runner one of the standard bearers for dystopian imagery in cinema.

“Scott brings an aerosol, neon palette to Blade Runner …,” curator Rhidian Davis would explain. “[the film] has rebooted, updated and colourised a lot of the tropes of film noir. It pushes the embryo of noir to give birth to something new. It takes noir into sci-fi in the same way Star Wars takes the epic, samurai adventure into sci-fi.” Famed cyberpunk author William Gibson would agree, suggesting that, “Blade Runner changed the way the world looks and how we look at the world.” Guillermo Del Toro, a director also known for his unique and sumptuous visuals, described the movie as, “one of those cinematic drugs, that when I first saw it, I never saw the world the same way again.”

Scott’s mesmerising neo-noir metropolis was originally inspired by Edward Hopper’s famous 1942 oil painting Nighthawks, a noirish image of a sparsely populated downtown diner that illuminates a dark urban streetscape, as well as the science fiction comic art of French illustrator Jean “Moebius” Giraud. The film’s aesthetics were also inspired by futurist architect Antonio Sant’Elia, a huge influence on modern architecture, despite failing to complete the majority of his projects. Scott hired concept artist Syd Meade, a fellow fan of the Métal Hurlant comics which Giraud worked on, production designer Lawrence G. Paull and art director David Snyder, who shaped and refined the towering power structures and dilapidated cityscapes, helping to forge some of the most impressive model work ever created. In terms of sheer scope, imagination and visual splendour, that model work, and its capturing, has arguably never been bettered.

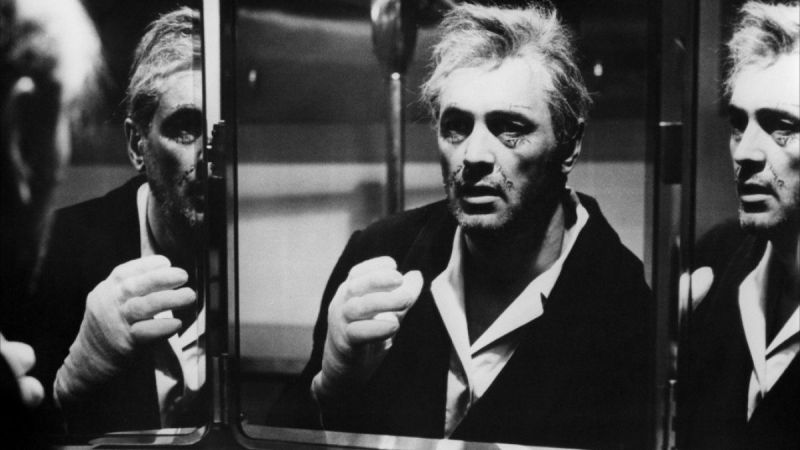

The actor responsible for inhabiting Scott’s world is none other than Harrison Ford. Ford, who had already immortalised himself as both Han Solo and Indiana Jones by the time Blade Runner hit theatres, was one of the most recognisable faces in cinema. Solo and Jones were adventurous, lovable rapscallions with an endearing cockiness and a heartwarming sense of irony. When you think of Harrison Ford, those are the characteristics that first leap to mind, so it was perhaps something of a risk to bring him back into the sci-fi fold as the humourless, emotionally monotone Rick Deckard, a character who comes out of retirement to assassinate a group of replicants who have escaped Earth’s outer colonies. The original theatrical cut would add a voice-over track that was designed to make events clearer to a mainstream audience. In doing so, they pushed the noir envelope even further, humanising Deckard to some degree, something else that audiences could relate to, but it doesn’t age well. Not only does it consistently drown out the film’s extraordinary soundtrack, which tells its own story, the ambiguity and sense of mystique are sacrificed for mundane expositional convention.

Replicants are like any other machine. They’re either a benefit or a hazard. If they’re a benefit, it’s not my problem.

Rick Deckard

In the Final Cut, Deckard’s ex-police is a conflicted private dick straight out of a Raymond Chandler novel, a depleted Humphrey Bogart haunted by questions of humanity and mortality. He doesn’t embrace the thrills and spills of blockbuster heroism. He clings to the neon-tinted shadows and reluctantly ekes out a living, trawling a rundown metropolis in search of lives to exterminate. He’s a hero to some, a monster to others, and beneath the icy façade he seems begrudgingly, uselessly aware of this. He reminds me a little of William Munny in Clint Eastwood’s genre-reviving western Unforgiven, a character as beleaguered by his environment as he is made for it, and, depending on how you look at the film, ‘made for it’ could very well be taken literally.

2019’s Los Angeles has been shaped by Eldon Tyrell’s Tyrell Corporation, a global tech firm that specialises in the manufacturing of androids known as replicants, their headquarters towering, pyramid-shaped structures on the outskirts of a ravaged city. Replicants are manufactured as slaves, each featuring different attributes that make them suitable for specific jobs. They’re mostly functional creations used for manual labour, but equally oppressed variations exist, some hiding among humans, others searching for eternal life. Daryl Hannah’s disquietingly vague, ‘basic pleasure model’, Pris, is little more than a prostitute created for the pleasures of man, a high-tech sex doll born into a life of physical and emotional redundancy. Others are ego models, prized projects who are perhaps just a little too cultured and self-aware for their own good, and for the good of humanity.

There is, of course, the theory that Deckard is actually a replicant himself, the addition of the unicorn dream and Gaff’s leaving of the unicorn origami proving hugely suggestive along with various other clues — many of them credible, others a little more tenuous. The unicorn dream is a beautiful, ethereal scene which seems completely at odds with Deckard’s cold fish persona. Is this a hint that Deckard has memory implants too, or is he merely schooled in supressing such emotions?

Interviews with cast and crew members have shed no definitive light on the matter. Screenwriter Hampton Fancher has claimed that he wrote the character as a human, but wanted the film to have a degree of ambiguity, which the best art typically possesses, and Ford has gone on record as saying that he played the character as a human, something that he and Scott have agreed on in the past. Scott has also suggested that Deckard is in fact a replicant, further flaunting the movie’s sense of ambiguity. Ambiguous endings are always the most talked about and memorable, allowing audiences to ponder events long after a film’s running time, to develop a story beyond what we’re presented with. Whether you believe that Deckard is a replicant designed to identify and assassinate his own kind, or a barely human buoy just managing to stay afloat in a dead sea of emotional despondency, is besides the point. It’s the not knowing that’s essential to the film’s enduring power and Deckard’s fascinating relationship with the quietly complex and utterly tragic Rachael.

Blade Runner‘s human themes are timeless, but the film is also something of a speculative powerhouse in its depictions of a future society. The world we now find ourselves in is not too dissimilar to Scott’s decades-old critique on the dangers and dehumanising extravagances of deregulated capitalism, which thanks to evolving technology and the increased fury of planned obsolescence, has gone from strength to strength. Today, we’re not exactly knee-deep in celestial colonies, and we’re still a million miles from a world in which artificial life roams undetected (though information phishing and increased surveillance might be considered today’s equivalent), but Scott’s vision of 21st century life is eerily accurate. If he’d set the movie fifty years later, who knows where we’d be.

Thanks to the pollutive excesses of a global economy, we’re already past the point of no return with global warming and the very distinct possibility of complete ecological meltdown, something that has been refuted by power’s insatiable appetite for maintaining the ‘natural order’ and pushing the limits of technological advancement. More and more species of life are nearing extinction, and pretty soon we’ll have no choice but to terraform and flee the planet. Automation is usurping humanity in working sectors such as the retail industry, AI evolving to the extent that big tech companies are already preparing for a remote world, algorithms becoming increasingly sophisticated. There’s nothing more dehumanising than social media, an almost illusory realm of tenuous relationships that normalizes and promotes misinformation and disseminates fear and hatred, oftentimes through fake accounts known as ‘bots’.

Scott had more than a little help in creating such an astonishingly prescient future. In fact, the filmmaker included, Blade Runner is something of a collaborative effort from three of the most innovative and influential artists of the late-20th century. The literary source material for Blade Runner, Phillip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, may not have the cinematic appeal of the adapted screenplay, but all the elements are there. Thematically, this is very much Dick’s vision.

In the book, Deckard takes the ‘retiring’ jobs not because he is forced to, but to buy a synthetic animal to compete with his neighbours, a commentary on the vanity of consumerism. The adapted screenplay doesn’t have time for such unabashed satire, but Dick’s paranoid outlook and tendency to draw comparisons between synthetic life and its corrupt human counterparts provides the movie’s thematic core. Dick is a hugely important figure in science fiction, influencing not only Scott, but a whole generation of writers and directors, including Terry Gilliam (Brazil) Richard Linklater (A Scanner Darkly), and even Stephen Spielberg (Minority Report). He may not have been the most stylish of writers, but conceptually he had very few peers.

A notorious recluse during his twilight years, PKD would confine himself to his room for long periods, often disappearing for days on end, abandoning his family and returning home after week-long benders with fresh ideas that would consume him absolutely. His later books were based on a concept known as VALIS or Vast Active Living Intelligence System, the author’s gnostic vision of an extra-terrestrial God who enlightened him with a knowledge beyond humanity, ideas explored in personal writings of biblical proportions. Dick spent years convincing himself that he was being monitored by the US government, a belief that would have him spiral into a personal vortex of often debilitating paranoia. Prone to fits of erratic behaviour, he once set fire to a pile of manuscripts on his doorstep out of sheer frustration. And no, he didn’t have them backed-up on disc.

By the time Blade Runner was due for release, PKD was a shell of the man. Two weeks before his death from a sudden stroke at the age of 53, he was invited to a personal screening of Blade Runner as a way to assuage his fears that Scott’s vision might tarnish his own, but Dick would leave with altogether different concerns. Speaking to author Paul Sammon for his book FUTURE NOIR: The Making of Blade Runner, visual effects expert David Dryer would recall, “I got a call from one of the ladies at the production department saying that Phillip K. Dick was coming down at three in the afternoon for a screening. She told me to assemble an effects reel showing the best of the best. So I did. I planned on showing it to Dick in EEG’s screening room, which was pretty remarkable… I could tell right away that Dick was unhappy; he acted like somebody with a burr up their ass. First he started kind of grilling me in this grouchy tone about all kinds of things ― he wanted to know what was going on, told me that he’d been very unhappy with the script… Dick didn’t seem impressed, even when we showed him all the pre-production art and the actual models we’d used for certain effects shots.’

Dick would demand a second screening of the specially arranged material. Afterwards, he would find himself consumed by a far more worrying notion. “How is this possible? How can this be?” he asked. “Those are not the exact images, but the texture and tone of the images I saw in my head when I was writing the original book! The environment is exactly how I had imagined it! How’d you guys do that? How did you know what I was feeling and thinking?” Dryer would cite this as one of the most satisfying and successful moments of his career, but knowing Dick’s history of self-delusion and paranoia, there’s every chance that Dryer missed the point entirely.

Unfortunately, Dick never got to see the finished article, which meant that he never got to experience the film complete with one of the its most vital elements. The sheer importance of Vangelis’ musical contributions are absolutely vital to Blade Runner‘s majestic world-building. His transformative score, one of the most incredible, befitting and life-inducing ever imagined, is a work of pure genius, a colossal arrangement that aches with emotional resonance; bold and desolate, yet capable of acute empathy and exquisite tenderness. For my money, his vision of an oppressive technological future is just as important as the director’s in capturing the movie’s central themes of loneliness and fear, and ultimately the question of what it is to be human. His prodigious blend of softly human melodies and robotic nuances communicate the kind of emotions that are impossible to achieve through imagery alone, and it’s just as effective as a standalone work, perhaps even more so, because it lends so much to the imagination.

Vangelis isn’t your typical composer. A synth innovator who would influence some of the medium’s finest, his albums were stories in their own right, conceptual arrangements with visually rich sounds that beg for thematic interpretation, but artists of that calibre can be understandably precious about their work and how it is presented, his relationship with Scott becoming rather prickly rather quickly. Vangelis was never going to produce a piece of music determined by the film’s order of events, creating or adding a series of original compositions that worked as a collective and told their own story based on “the film itself ― the characters, the settings, the atmosphere, the story, the whole thing.”

Commerce is our goal, here. More human than human.

Dr. Eldon Tyrell

For reasons that have never been revealed, disputes over the material would endure for more than a decade. Having worked tirelessly for almost a year composing, arranging and producing every aspect of the music, Vangelis refused to release the album just prior to his death, a legal wrangle dragging on for 12 years. During that time, the Blade Runner OST became one of the most sought after of the era, leading to various low-quality reproductions culled from the film’s audio snippets. An exceedingly rare bootleg version even emerged in 1982, one rumoured to have been the work of the film’s sound engineers. It wasn’t until 1994 that the 12-track album was released, an astonishing compilation that omitted much of what was featured in the film and included brand new, unused compositions, only adding to the album’s lore and the idea that there was still unreleased material to be discovered. A 25th anniversary edition, released in 2007, included further material, though circulating bootlegs contain versions that are even more comprehensive.

Vangelis’ contributions are also vital to Blade Runner‘s vision of a future overwhelmed by humankind’s undying fascination with progress, and, more specifically, progress for the few. The film featured a strong Japanese aesthetic at a time when American-made businesses were feeling the sting of Japan’s manufacturing giants, the emergence of modern, superior technology threatening obsolescence for a disgruntled generation raised on Henry Ford ethics. Thanks to Eldon Tyrell, the threat of obsolescence is even more widespread in a fictional 2019. Replicants are physically stronger than their human counterparts, while being of at least equal intelligence to their creators. They move and behave exactly like humans, are valuable assets who provide superior, cost-free labour, but as far as the law is concerned their lives are cheap. Their assassination is nothing more than standard procedure.

How ‘human’ replicants are is hard to define since humanity is a tenuous definition itself; the very notion that a species would create superior beings in their own image for the purposes of oppression and control is proof of that. Those hunted by Deckard seem ruthless and manipulative for the most part, but would humans be any different if their own lives were under constant threat? Replicants are referred to as “skin-jobs”, a derogative term with racial and historical overtones, and their place in the world is reminiscent to that of African-Americans during US slavery, events that dehumanized an entire race for the purpose of financial gain.

Replicants are born fully formed without the time to develop emotions at a human level, which becomes increasingly problematic as they age. They are also burdened with extremely short lifespans of approximately 4 years, plagued by the knowledge that, like humans, they were made to perish, but unlike humans, replicants understand why and when they’ll die and who’s responsible. They don’t have the luxury of the unknown, of faith and the possibility of life beyond life. They are remarkable but treated unremarkably. Imagine having to deal with the prospect of mortality with such immediacy, the anger and frustration at being given such a short and finite lifespan, the knowledge that someone has, quite ruthlessly, determined such a fate.

What replicants lack in emotion they more than make up for in survival instinct, which is part of what makes them so ruthless. Pris (Daryl Hannah) is an attractive Nexus 6 model whose main function is to provide male companionship, and she naturally utilises the tools she has been given by her corporate god, using her sexuality to help manipulate lonely genetics designer J.F. Sebastian (William Sanderson). Sebastian holds the key to a meeting with reclusive mogul, Tyrell (Joe Turkel), and the possibility of life extension. Their quest, however cold and ruthless, is a case of survival, and the survival of any species, synthetic or otherwise, will be fought for at all costs. In the book, Pris shows her lack of humanity by slowly pulling the legs off a desert spider with childish glee, much to the disgust of her companion/prisoner. In the movie she is harder to interpret. Sometimes she appears naïve and frightened, other times calculated and heartless.

Deckard is able to identify replicants using the Voight-Kampff machine, an interrogation tool not too dissimilar to the polygraph that measures bodily functions such as respiration, blush response, heart rate and eye movement in response to questions that deal with empathy. Love interest Rachael, played with subtle vacancy by the elegant Sean Young, is a new kind of replicant, one who believes herself to be human due to implanted memories that were borrowed from Tyrell’s niece, and who is therefore harder to detect (it takes more than 100 questions to detect her instead of the usual 20-30). Rachael is also the only replicant who Deckard, enchanted by her beauty and sympathetic towards her sadness, seems to have empathy for. Rachael was tricked into thinking that she is human and is desperate to prove as much, yearning to be viewed as someone rather than a mere thing with sub-human rights and liberties. Deckard, replicant or otherwise, is someone who undertakes what might be considered inhuman acts as a profession. It is safe to suggest that he understands Rachael’s sense of inner-conflict only too well.

Deckard’s replicant status notwithstanding, Rachael is the movie’s greyest area, not least because she has spent her entire life believing that she is human. The boundaries are so open to interpretation, the sense of conflict so hopeless and excruciating. When Deckard tries to become intimate with Rachael, she lacks the passion and desire to reciprocate in a way that is borderline-robotic, but she has also been stripped of her identity, is unable to trust anyone or anything, particularly her sense of self. Later, she saves Deckard’s life during a deadly conflict with fugitive replicant Leon, but does she feel anything for Deckard at this point, or is killing one of her own merely an extension of her desire to be human? Following Leon’s murder, Rachael goes from benefit to hazard, from insulated Tyrell novelty to potential blade runner target. Is her union with Deckard merely survival instinct at this point, manipulation as a means for self-preservation? Is anything she feels pure and unaffected? Is there even a distinction to be made between replicants and humans in this regard?

Tyrell’s greatest creation, Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer), proves even more of an enigma, an anomalous entity who is much harder to relate to for the most part. Roy is too intelligent to be considered human. Just as human beings have a tendency to see inferior life as irrelevant, he seems to view humans as cattle — useful when necessary, but unenlightened and ultimately disposable. As a product of, and a slave to humanity, the idea of ‘cattle’ is ingrained in Batty, his seeming lack of humanity what makes him so human.

Batty is Blade Runner‘s true protagonist, the one who can see the distinctions, or lack thereof, with the most clarity. He can see the flaws inherent in man, the flagrant injustices and lack of compassion therein, and he looks to correct that with the same ruthlessness and lack of compassion. In Roy, Deckard meets an adversary who is just as morally ambiguous, who routinely commits immoral deeds despite his superior intelligence and god-like aura, and moreover because of that fact. Made in mankind’s image, Batty is the embodiment of a species that has superiority, wickedness and self-destruction wired into it, one that is capable of both abhorrent acts and unspeakable beauty.

I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe. Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. I watched C-beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhauser gate. All those moments will be lost in time… like tears in rain… Time to die.

Roy Batty

Emotionally, Batty is representative of humanity in its most savage, unaffected form, and while the benefit of vast intelligence allows for complex analysis, appreciation and even understanding, his inability to accept or deal with them makes him a threat to humanity’s sense of order, a hazard not a benefit. His expressions go from anger to sympathy with such capriciousness that it’s hard to decipher exactly how he feels, or if he actually does. His fierce pursuit of extended life and the frustration that he expels after realising that for him, there is no such thing, is distinctly human, as is his instinct to apologise to the horrified J. S. Sebastian after subjecting him to Tyrell’s fatal eye-gouging. Roy no longer has reason to deceive or manipulate his unwilling accomplice following his brutal act, so why does he apologise to a man of such little relevance, and to what degree is it genuine? It is natural for mankind to fear that which it doesn’t understand, especially if that which it fears is superior. What we can relate to as humans is Roy’s fear of mortality, his pursuit of freedom and individuality, his sense of injustice.

It is this kind of ambiguity that defines much of Dick’s work when it comes to questions of identity and what it is to be human. Inspired by the changing landscape of California, a rural paradise that was bulldozed into urban submission, the writer took umbrage with a consumer landscape that dealt in disposables, detracting from the idea of the individual. A cold streak of technophobia emerged, everyday technological fancies, many of which bound to obsolescence, acquiring an insidious sentience. Everyday household items were portrayed as intrusive, transformative implements, the distinctions between humans and machines growing increasingly blurred. In Blade Runner, Scott gives Dick’s biting sense of speculative wit a cinematic makeover, and in many ways his characters are richer, particularly the towering and ultimately doomed alpha male of a synthetic yet distinctly human race.

Once Roy accepts his fate and his fury dissipates, it becomes clear that he is capable of empathy, even in regards to the enemy, which is more than we can say for the majority of his human counterparts. The ease and relish with which he hunts Deckard during Blade Runner‘s climactic battle is significant in establishing his capacity for vengeance, but perhaps more significant is the mercy that he shows the man — if indeed he is a man — who was hired to kill him. Roy knows that his own life is drawing to a close, but instead of letting Deckard fall to his death he spares his would-be assassin, going as far as to rescue him from impending doom. Rutger Hauer famously ad-libbed the movie’s finest monologue, and it is through Roy’s words that we are able to gain a further understanding of his capacity to appreciate life and all that fills it. This, too, is a distinctly human quality, as is the need to communicate his passions to another living creature, but in the end perhaps it comes down to the simple fact that, like humans, Roy has no desire to die alone.

For my money, Blade Runner is Ridley Scott’s finest achievement, an opinion that is far more common today, but for many years the film, in its various forms, struggled for acceptance after underwhelming box office returns, and still divides opinion more than fans would care to believe. It doesn’t have the adventurous spirit of something like Star Wars, the knife-edge tension of Alien, the smash-mouth mayhem of Mad Max II: The Road Warrior. It is careful and considered, concerned almost entirely with ambiguity. It asks more questions than it answers, which can be frustrating for audiences who embrace sci-fi for the thrills and spills. Incredibly, Blade Runner was mostly criticised for its lack of a human story, some viewing the movie as an exercise in style over substance. It’s plenty stylish, but when a film raises questions about what it is to be human in a society that has all but forgotten, a lack of humanity seems par for the course.

Director: Ridley Scott

Screenplay: Hampton Fancher &

David Peoples

Music: Vangelis

Cinematography: Jordan Cronenweth

Editing: Terry Rawlings &

Marsha Nakashima