Revisiting a cerebral creature feature in an era of environmental crisis

In the 1970s, man’s inhumanity to the environment started catching up with us. Nightly news programs featured stories of lakes that were biologically dead with aquatic carcasses lining the shoreline. Rivers so polluted they caught fire. Mass die-offs of plant and animal life. Landfills spreading across the countryside, mass graves for our carelessly discarded consumer acquisitions.

The environment was yet another worry in a decade filled with them, another issue of life-threatening concern that seemed to have no answer. The air was dirty, the water was undrinkable, the food unfit to eat. And it was all our fault. The fears of environmental catastrophe in the 70s and the self-loathing dread that we had it coming gave way to a run of fascinating science fiction films in which Mother Nature delivered a reckoning for all our years of wantonly abusing the planet. And that reckoning came in the form of crazed animals preying on man at his most vulnerable, mutant rats as big as tractors, or hordes of killer insects.

Phase IV, director Saul Bass’s 1974 head scratcher, holds a special place in this pantheon, an environmental revenge fantasy that aimed to be more cerebral than similar films of the early 70s. Unlike the squirmy amphibians that overrun a palatial estate in Frogs or the mutated killer rabbits that terrorize a small town in Night of the Lepus, the ants in Phase IV have a larger, more insidious plan in mind.

Bass got his start in Hollywood in the late 1940s designing print advertisements for motion pictures. This work eventually led him to create title sequences for films. His first was for Otto Preminger’s 1955 noir The Man with the Golden Arm. Bass believed that opening credits offered an opportunity to get creative, to tell a story in a microcosm. He went on to create iconic title sequences for an array of classic films by Preminger, Alfred Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick, William Wyler, and John Frankenheimer. Bass took second-unit director work on some of these and other features, getting to know some of the biggest directors and producers in Hollywood. In 1968, Bass and his wife and creative partner, Elaine, won the Academy Award for their documentary short subject film, Why Man Creates.

Paramount Pictures approached Bass in 1973 to direct Phase IV, a story about super-intelligent ants aiming to replace humans at the top of the food chain. It’s easy to see how this premise could take a schlocky turn, but Bass saw promise in the project. The screenplay was written by Mayo Simon, who collaborated with Bass on Why Man Creates, and it was written to be more than just a drive-in creature feature. It was thoughtful, creative, and contemplated the effects of man’s abuse of the environment. Bass took up the challenge, eager to put his signature style to work on a major motion picture of his own. Paramount looked to Bass to bring a deft touch to the script, banking on his Oscar-winning talent and years of proven visual artistry to create a box-office hit.

Yes, a tragedy. I don’t understand it. They accepted the order. Why should they come here? Irrational behaviour. Very sad. Now just look at this, James. Consider the execution of this manoeuvre, in order to explode the generator, they had to create a living chain.

Hubbs

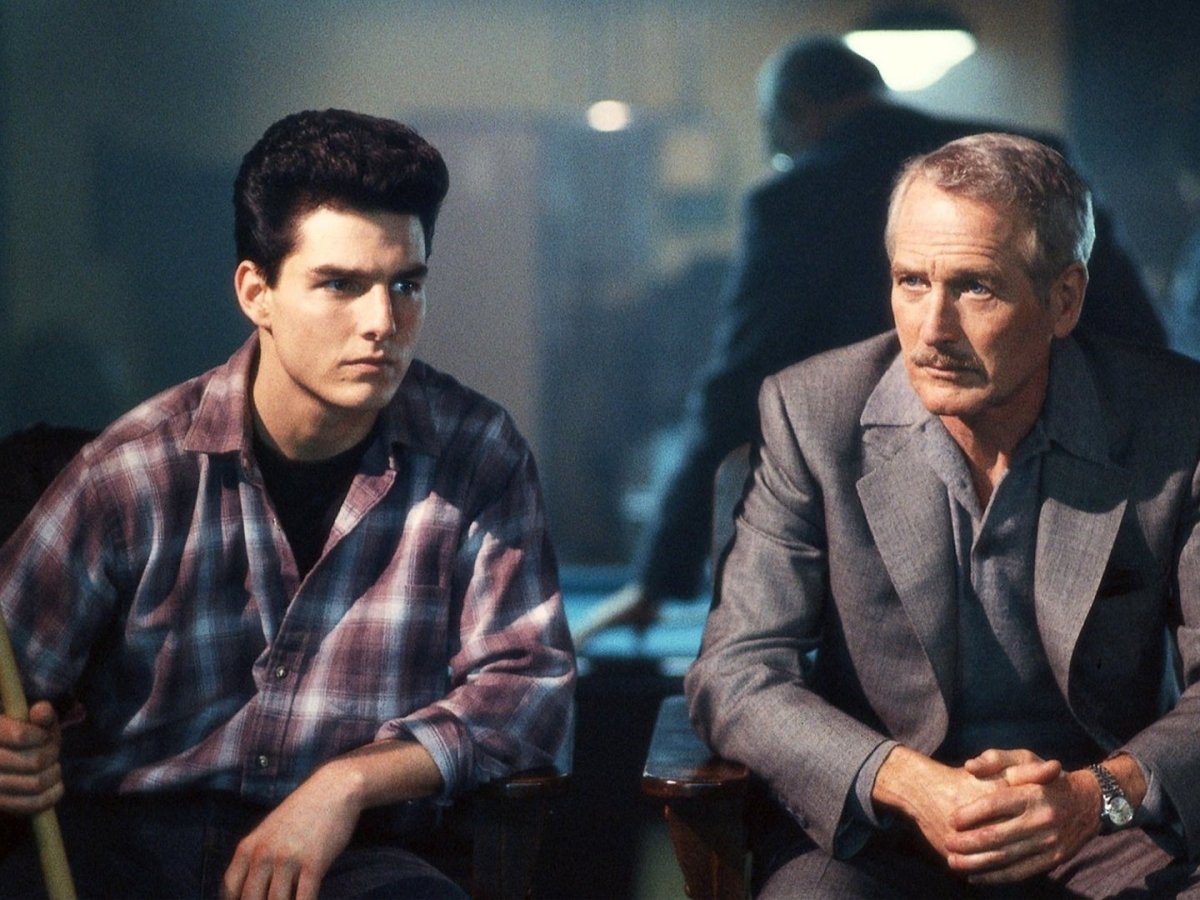

When the film opens—without any credits, ironic considering Bass’s filmmaking background—Earth is just emerging from a cosmic event that is never described. Though it appears to have no impact on humans, it greatly affects the behavior of the world’s ant population. Only one man notices, a grizzled scientist named Ernest Hubbs played with scenery-chewing aplomb by Nigel Davenport. Hubbs observes that various ant species are coming together and behaving more aggressively toward other creatures, something that entomologists wouldn’t think possible.

Hubbs is joined by another scientist, James Lesko, an early role for long-time character actor Michael Murphy. They travel to an abandoned housing development in the Arizona desert. The last of the local inhabitants tells Hubbs about how insects chased out the rest of the population while Lesko ogles their teenage granddaughter. The scientists build a sealed dome in the desert to study the ants, surrounded by the latest available technology. When Lesko’s attempt to communicate with the ants via radio waves fails, Hubbs falls back on more primitive methods and blows up the impressive collection of 30-foot sand towers the ants have built in the desert. They are fantastic to look at and a reasoned study of them could reveal a lot about what the ants are up to, but yeah, screw ‘em. Blow up their towers. That should stir a little chatter from the six-legged freaks.

Ants make for good screen monsters. Famous for their hive mind, their freakish strength, and their vast numbers—one quadrillion at last count, or 1.6 million ants for every man, woman, and child on Earth—ants are both fascinating and frightening. They move about their work with passionless, relentless purpose, and we should consider ourselves lucky that they don’t act in concert the world over. Ants have a larger population than any other animal species, which could make them an existential threat if they ever decided to band together. Scientists claim that such a phenomenon could never take place among the 12,000 different types, but that was before Phase IV.

Hubbs becomes the Ahab of the story, bitten by an ant and slowly going mad while his wound festers. He is quickly convinced that the ants are out to destroy humanity and becomes more single-minded in his mission as the film progresses. After the grenade launcher fails to produce the desired results, Hubbs fires off the facility’s prodigious supply of insecticide, killing everything for hundreds of yards, including that last remaining family in town, who are caught in the rain of toxic sludge as they try to seek refuge. The beautiful granddaughter, Kendra, survives, as do the ants.

In the typical fashion of the obsessed, Hubbs’s repeated failures only stir him to double down on his strategy. The callous way in which he approaches his work, and his gross, obviously infected bug bite, make him the villain of the piece. The ants have gained superintelligence and communed (Phase I), wiped out all other natural predators (Phase II), and are now prepared to take on humans for the heavyweight title (Phase III). But in the self-loathing fashion of 70s environmental revenge fantasies, there simply has to be a human behind it all, a government official, a military officer, or a mad scientist. Hubbs, who acts more like an exterminator with a PhD than an entomologist, fits the bill perfectly. By choosing confrontation over communication and dominion over accommodation, Hubbs embodies humanity’s worst traits in our relations with the environment, and comeuppance is nigh.

Lesko wants to pursue a more reasoned course by opening communications between the species, and he believes he is making progress. But Lesko finds himself easily distracted once Kendra is on the scene, and though he is concerned for her safety, he sure does touch her a lot, even for the promiscuous 70s. Putting his hand on her shoulder, putting his arm around her, doing a lot of close talking. These scenes and some of the dialogue between Lesko and Hubbs bog the film down, revealing Bass’s limits as a director. His visual artistry is spot on, but the human side of the film lags.

The parallel story of the ants is where the action is in much of Phase IV. We follow them throughout as they learn about their nemesis, battle back from grenade and chemical attacks, mourn their dead, and plot their next move. The cinematography of the extended ant sequences is mesmerizing, thanks to the work of wildlife photographer Ken Middleham. The ants are displayed in a way that imprints emotion on them for the viewer, and it is so impactful that we connect with the ants and consequently root for them to defeat the humans. Don’t be alarmed. This is only natural in an environmental revenge fantasy.

In the case of Phase IV, it’s not too hard to see the humans as the problem. When they are trapped in their dome with no electricity thanks to the work of the ants, it’s hard to generate sympathy. They are in this situation through a series of rash, impulsive, inane, and counterintuitive decisions. Regarding their fate, we are at best curious whether they will find a way out or do something dumb again. For Hubbs it’s the latter when he is buried alive in a trap outside the dome. Lesko and Kendra are saved for an ant/human mind meld (Phase IV). They emerge from the hive hand-in-hand, accepting that this was what the ants wanted all along. Man and ant can live peacefully together, so long as both creatures know who’s boss.

For all the talk about bringing a bold new vision to cinema, the creative relationship between Paramount and Bass was strained throughout the production. Bass had a singular vision in mind for the film: very visual with psychedelic energy, a real eye-opening trip. Paramount wanted a good-looking film for a wide audience; what Bass gave them was a great-looking film for a narrow audience.

The studio cut Bass’s original ending, an event that drummed-up controversy in the film community for years. The original ending of Phase IV is much more involved than Lesko and Kendra becoming ant ambassadors. In an extended climactic montage worthy of a Pink Floyd video, humans become hive-like, traveling through mazes, tracked everywhere they go, living at the behest of their insect overlords. Bass’s intense and information-packed imagery nails home what happens when the human race is subjugated by ants. It’s the perfect feel-bad science fiction ending for the period, and it fits with the visual tone set by the rest of the film. The studio seemed to think that this ending was muddled and chopped it, resulting in an even more muddled ending for the theatrical release.

You see what we’re doing, we’re running lines from these fuel tanks and if those ants get over that water trap we’re gonna set fire to this here ditch and watch ’em all burn. What do you think?

Mr. Eldridge

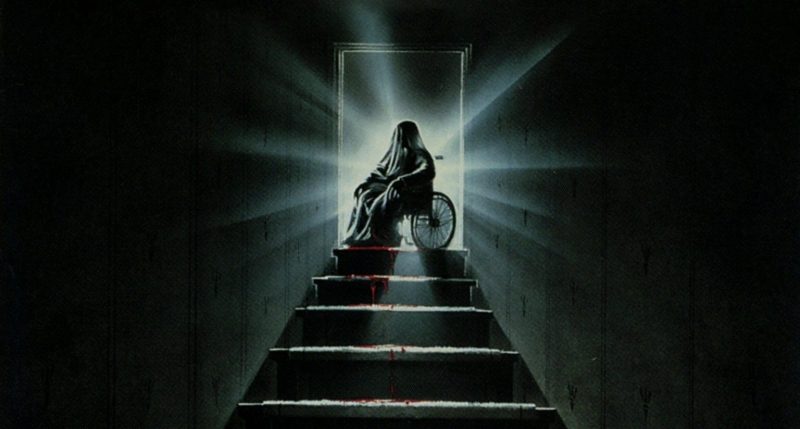

Paramount also botched the marketing of Phase IV, leaving Bass out of the loop. Directors may not always be natural marketers for their films, but this is Saul Bass. The reason he was able to do the film at all was because of his stellar career as a designer. Bass might have framed the film as a science fiction head trip, a meditation on man’s place in the universe, more 2001 than Frogs. But that’s not the movie that was sold to audiences. The studio marketed Phase IV as a science fiction monster movie. The poster portrayed an apocalyptic world of fire and brimstone, ravenous invaders controlled by a terror from space. That might be a cool flick in its own right, but that was not Phase IV. Audiences that saw the film opening week felt ripped off, and by the second week there was no audience.

Phase IV was a total commercial failure at the box office. Bass’s heavy reliance on images over dialogue frustrated audiences and critics. He was also not the best at guiding his actors, allowing them to fall into one-note clichés of their characters. A few fans looked past the film’s flaws, choosing instead to appreciate the visual impact of the work and the greater message in Bass’s vision. Phase IV was kept alive on late-night television for years, surviving every home video format change, and is currently available on Blu-Ray.

Bass never made another feature after Phase IV, but he continued to make film credit sequences with his wife, Elaine. They worked into the 1990s, creating opening title sequences for films by James L. Brooks, Penny Marshall, John Singleton, and Martin Scorsese. Bass also designed numerous widely recognized corporate logos for AT&T, United Airlines, Quaker Oats, Warner Communications, and others. He died in 1996.

In 2012, Bass’s original ending to Phase IV, rumoured destroyed or lost, turned up in the archives at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. It was screened in Los Angeles to much fanfare with a restored print of the original film ― just in time to inspire a new generation of science fiction aficionados to the delightful weirdness that is Phase IV.

Director: Saul Bass

Screenplay: Mayo Simon

Music: Brian Gascoigne

Cinematography: Dick Bush

Editing: Willy Kemplen

Phase IV is such a strange and unsettling film. I really like how the ants and their collective intelligence are portrayed in the film, and how the humans end up going form studying them into virtually being under siege by them. It a great and very underrated little sci-fi film!

LikeLiked by 2 people