A case of conscience and crisis in Kubrick’s late to the party Vietnam epic

It was several years after the conclusion of the Vietnam War before Hollywood started making serious films dealing with the conflict. The big studios didn’t have too much to say about the war while it was taking place. They wanted to make movies, and make a lot of money in the process, but taking on divisive, passionate topics is not a traditional gateway to big box office returns. And there were few things in the late 1960s and early 1970s as divisive as the Vietnam War. Massive demonstrations with thousands of people, college campus takeovers, riots breaking out in the streets, young men burning draft cards; it was the most chaotic time in American history since the Civil War. The last thing a Hollywood studio chief wanted was to make a big budget movie about Vietnam and bring that chaos onto the studio lot.

Hardly any films released during the war addressed it directly. The one notable exception was John Wayne’s The Green Berets, released on July 4, 1968. With an Independence Day release date, you can guess where the Duke’s picture stood on Vietnam. In the film, Wayne’s Green Beret colonel teaches some lessons in patriotism to a cynical American reporter covering the war in Southeast Asia. And of course, along the way they win local hearts and minds while taking out Vietcong baddies by the bushel. The film was savaged by the press and the anti-war movement, but it found a loyal audience among those who believed whole-heartedly in the fight against communism. Such was the divide in America at the time.

American audiences had to wait a whole decade for another Vietnam film. Director Sydney J. Furie made The Boys in Company C in 1978, a film that was in the vein of M*A*S*H in that it revealed the absurdity of war and the madness of how we have come to bureaucratize mass slaughter, but Company C wasn’t playing for laughs. The film was well-received, but not a runaway hit. It was notable in hindsight, however, for featuring a retired Marine staff sergeant named R. Lee Ermey as the tough-as-nails drill instructor who seemed to specialize in torturing his cadets.

Later that same year came Michael Cimino’s epic The Deer Hunter. This film took the topic of the Vietnam War head-on. The tragic tale of a group of friends who are forever changed by their horrific experiences in Vietnam won the Oscar for Best Picture and was a critical and box office hit. The stigma of Vietnam in Hollywood had been lifted, and more films about Vietnam followed. Next came Francis Coppola’s phantasmagorical Apocalypse Now (1979), which was really more of an examination of the madness of war that just happened to take place in Vietnam. A few years later came Oliver Stone’s Platoon (1986), an Oscar-winning classic loosely based on the director’s own experiences as a soldier during the war.

Tonight, you pukes will sleep with your rifles. You will give your rifle a girl’s name because this is the only pussy you people are going to get. Your days of finger-banging ol’ Mary-Jane Rottencrotch through her pretty pink panties are over! You’re married to this piece. This weapon of iron and wood. And you will be faithful. Port, hut!

Gunnery Sergeant Hartman

While all this was going on, director Stanley Kubrick was quietly mulling a Vietnam film project of his own. He had met writer and Vietnam veteran Michael Herr in 1980 and the two men tossed around some ideas, but nothing stuck. Herr wrote a best-selling memoir of the war titled Dispatches and the narration for Coppola’s Apocalypse Now, but he was reluctant to relive his own experiences for a film. Kubrick came across a novel called The Short Timers by Gustav Hasford, another war veteran. The book had received rave reviews and, like many readers, Kubrick was hooked by its dialogue and stark realism. Kubrick, Herr, and Hasford set about adapting the novel into a screenplay in 1985 while Kubrick began diving deep into research, studying hundreds of photographs, documentaries, books, and newspapers. Along the way, he decided to change the title of the project, fearing that the term short-timer would be confused by audiences to mean that his film was about part-time workers. It actually refers to soldiers in the field who are close to the end of their term of service. Kubrick came across the term “full metal jacket” in a gun catalogue, which describes a type of small arms ammunition that uses a metallic shell for greater muzzle velocity and smoother loading in automatic weapons. Why non-military viewers would not be equally confused by the term full metal jacket seemed to escape Kubrick, but it’s a cool-sounding title for a movie.

Kubrick’s famously keen attention to detail and his legendary drive for perfection pay off in a big way with Full Metal Jacket. The film is, for all intents and purposes, flawless. The look is vintage Kubrick. There are long, studious shots that make the viewer feel like a voyeur, and the set design and the skillful use of primary colors make everything seem otherworldly yet familiar, like a fever dream. The score, written by Kubrick’s daughter Vivian under the pseudonym Abigail Mead, is an eerie synthesized melodic mix that deeply enhances the film’s moodier moments. The script lays out an array of intense and colorful characters and the dialogue crackles, thanks to Hasford’s novel, from which many of the lines were lifted directly. Over the course of its tight two hours, Full Metal Jacket takes the viewer through the entire spectrum of human emotions. We even find ourselves laughing out loud at several points, and then getting embarrassed for having laughed.

The structure of the film makes it unique among war movies, particularly those about Vietnam. The first 45 minutes of the movie are devoted to basic training. We get a detailed look at just where the killers we will see in “the shit” later came from, and like watching sausage getting made, it’s not pretty. From the film’s opening moments, the recruits at the Marine Corps Recruit Depot at Parris Island, North Carolina, are given the hardest time they’ve ever had in their lives. For the first ten minutes of the film, Gunnery Sgt. Hartman lays into them nonstop with insults, racial slurs, taunts, and even some physical abuse to get his point across. It’s all about weeding out “all non-hackers who do not pack the gear to serve in my beloved Corps.” R. Lee Ermey’s portrayal of Hartman is a legendary piece of cinema, one of the most memorable film characterizations in recent film history. It made the former Marine a star, and he remained solidly at work in film and television until the day he died in 2018. Ermey was originally hired to be a technical advisor for the film, but when Kubrick saw an instructional tape that Ermey made for actor Tim Colceri, who was in line to play Hartman, he hired Ermey on the spot. Colceri remained in the film in a brief role as an insane helicopter gunner who gets his kicks taking aim at Vietnamese farmers from the air.

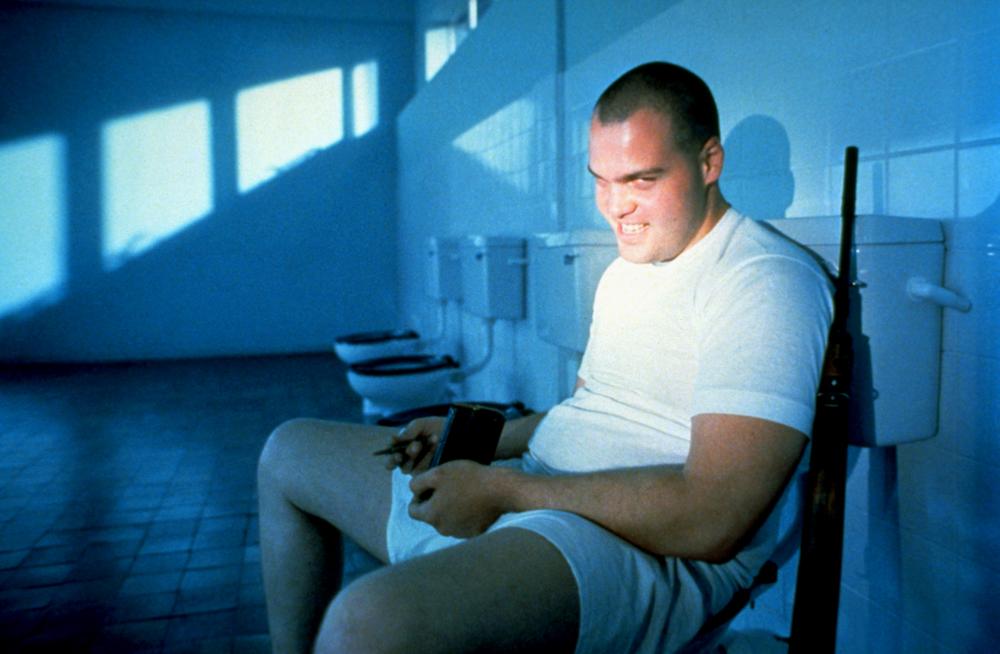

Hartman quickly zeroes in on Leonard Lawrence, a schlubby, dim-witted fellow who from then on is referred to as Gomer Pyle. Pyle, played to perfection by Vincent D’Onofrio, probably wouldn’t have amounted to much in the real world, but in the wartime Marine Corps, he doesn’t stand a chance. It’s hard not to feel sorry for the poor fool, whom Hartman mercilessly lays into without end in every scene. Pyle is made to sit sucking his thumb while the rest of his platoon perform calisthenics, march with his pants around his ankles and his thumb in his mouth, and he is also slapped, punched, and ridiculed repeatedly. At first it’s funny, but it gets sad after a while, because though Hartman seems cruel, we know that if Pyle doesn’t shape up, he is sure to get killed in combat, and maybe get his fellow soldiers killed with him.

Private Joker, the film’s main character and narrator played by Matthew Modine, is enlisted to help Pyle get his act together. It’s a losing proposition. Pyle doesn’t come around until after his fed-up platoon mates throw him a blanket party—in which Pyle is held down under a blanket while everyone takes turns whacking him with bars of soap wrapped up in towels. Pyle becomes a crack marksman, but he is also cracking up. He talks to his rifle and starts to take on a glazed, psychotic look. The night after graduation from basic training, Joker comes across Pyle in the head, sitting on a toilet loading a rifle magazine. Hartman shows up and, without taking in the fact that perhaps he has pushed Pyle a little too far, starts shouting at the crazed private, for which he takes a bullet in the heart. Pyle then promptly shoots himself.

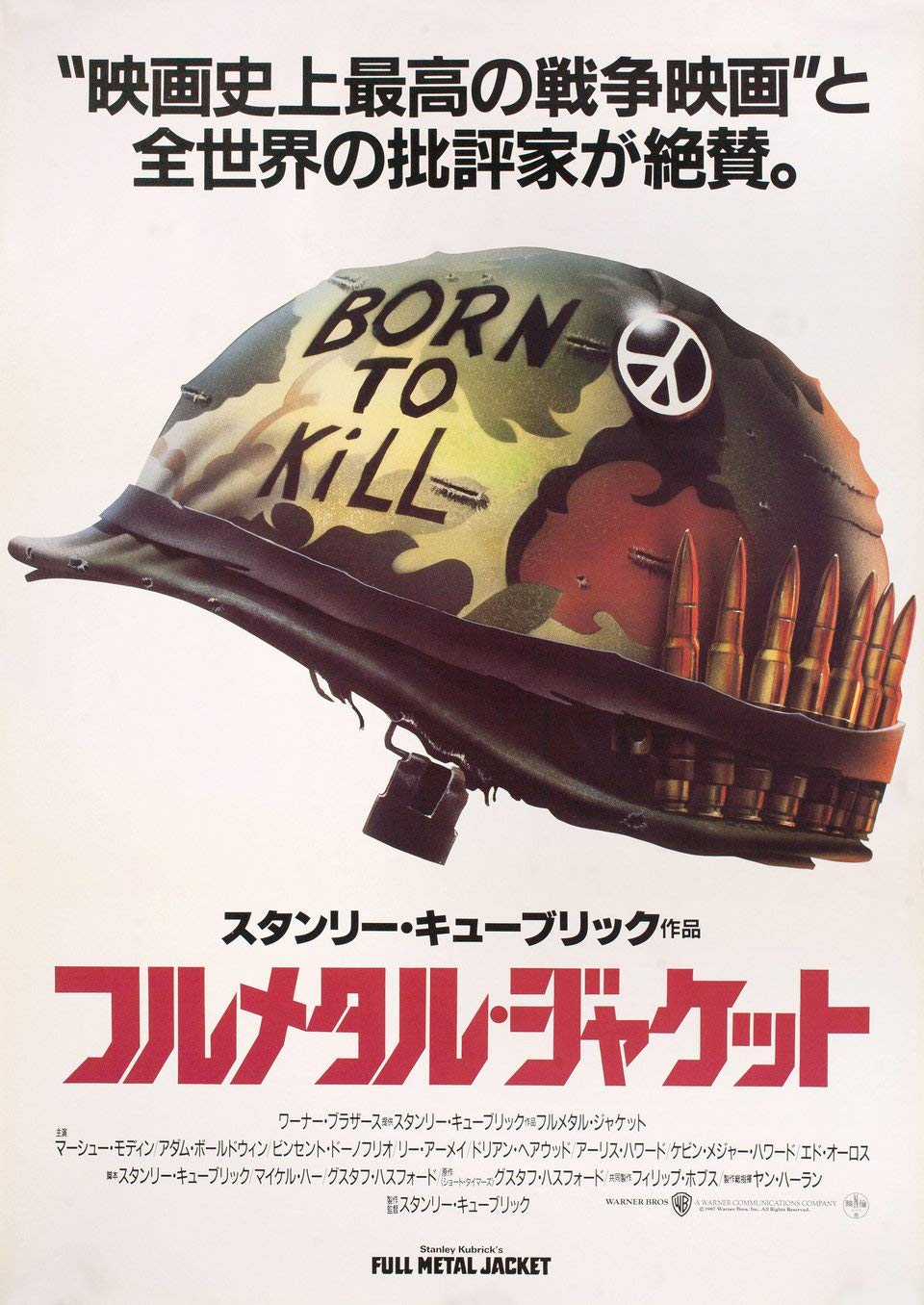

We switch from this grim moment to Da Nang, Vietnam several months later where Joker is now a correspondent for Stars and Stripes with his photographer Rafterman. Joker’s sharp wit and cynical viewpoint serve as Kubrick’s vehicle to communicate the insanity of Vietnam. Along with his mouth, which gets him into trouble more than once, he wears a peace button on his uniform and has “Born to Kill” written on his helmet. He is later called out for it by a Marine colonel played by Bruce Boa (General Rieekan from The Empire Strikes Back for all you Star Wars fans).

You write ‘Born to Kill’ on your helmet and you wear a peace button. What’s that supposed to be? Some kind of sick joke?

Colonel

Joker, his fellow soldiers in Da Nang, and pretty much the entire country of South Vietnam are caught unawares when the Vietcong launch the Tet Offensive. In real life, the January 1968 surprise attack by 80,000 Vietcong guerillas, backed up by 35 divisions of North Vietnamese Army soldiers, hit every major U.S. military installation in South Vietnam and stormed the U.S. embassy in Saigon. Contrary to popular belief, the offensive was a military failure for the North Vietnamese. They suffered massive casualties, and all their units were either wiped out or beaten back. The psychological blow to American forces and civilian support at home, however, left the U.S. rattled. Many Americans came to believe the war was unwinnable, and Lyndon Johnson’s presidency ended in failure as a result.

In the film, after helping stop the attack at Da Nang, Joker and Rafterman head to Hue City to report on the enemy siege. They link up with Joker’s friend Cowboy from Parris Island. Through a series of attacks and mishaps that take out his senior officers, Cowboy ends up leading his platoon, and Joker and Rafterman join the outfit. This sequence of the film is also unique in Vietnam War movies, in that the combat scenes take place in an urban setting. Much of the fighting in Vietnam took place in the countryside, where the Vietcong guerillas could make raids and easily disappear into the jungle. Consequently, virtually every Vietnam War movie takes place in the jungle as well. Kubrick, following the lead from Hasford’s book, takes us into an urban war zone, filled with burned out buildings and total devastation. The location that doubled for Hue was the old Beckton Gas Works outside London. In fact, all of Full Metal Jacket was filmed in England. Kubrick, who had lived in the UK since 1965, was not much of a traveler. Thanks to his status by the late 1980s as a master filmmaker, he had the power to bring the whole production to his backyard.

The platoon tries to cut through the city to link up with the rest of the American forces, but they get lost. A sniper lies in wait, taking out three soldiers, including Cowboy. Animal Mother, a hardened soldier with no love for Joker, or anyone for that matter, assumes command of the platoon. He leads Joker, Rafterman, and two members of the platoon into a building where they believe the sniper is located. Joker finds the sniper, a teenage Vietnamese girl, but his gun jams at the moment of truth. Rafterman shoots her down and saves Joker’s life. Lying on the floor and bleeding, the girl begs to be killed. Animal Mother demands they leave her to rot, but if she is to be put out of her misery, then he will only let Joker perform the deed. After a painful moment of hesitation, Joker kills the sniper. He is now hardcore. Joker, through narration, admits that he is in a world of shit, but he is glad to be alive and he is no longer afraid. In the film’s final moments, the members of the platoon make their way through the burning rubble of Hue City at twilight, singing the Mickey Mouse Club theme song. It is a darkly humorous moment, and after everything that has taken place on screen for the last two hours, it allows the viewer to walk away with the ghost of a smile.

In looking back on the film, it’s a bit of a surprise to see that Full Metal Jacket is a remarkably simple story. Basic training, witnessing the opening salvo of the Tet Offensive, dealing with a sniper, roll end credits. But within those few simple segments, an epic tale unfolds that gives the viewer a powerful lesson about the devastating toll war takes on the human soul. It’s a lesson no viewer of this film will easily forget, and it is one of the main reasons that Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket is quite simply one of the best war movies ever made.

Director: Stanley Kubrick

Screenplay: Stanley Kubrick,

Michael Herr & Gustav Hasford

Music: Abigail Mead

Cinematography: Douglas Milsome

Editing: Martin Hunter