It’s crime and punishment with Romero’s EC Comics styled horror anthology

We all know Creepshow’s impressive pedigree. A holy horror trifecta, written by Stephen King, directed by George A. Romero, special makeup effects and creature design by Tom Savini. We all know about innovative comic panel-style lighting, the masterful pacing, Ed Harris’ funky dance moves. Since its release in 1982, this five-act anthology has remained well loved and much discussed. It inspired two sequels and a television series currently running on Shudder. But has anyone ever looked into the murky moral lessons the original tales offer?

At its heart, Creepshow is a love letter to EC Comics’ line of brazenly grizzly, pre-code horror titles like Tales From the Crypt and The Vault of Horror. The comic book stories mostly followed a standard formula, a scheming ne’er-do-well profits over the fatal misfortunes of others only to face supernatural comeuppance at the end. It’s ironic that the pearl-clutching moral crusaders in the 1950s pounced on EC’s lurid themes and gory images as a gateway to juvenile delinquency but failed to pick up on the underlying morality: bad people come to bad ends.

Creepshow carries this morality through its connective tissue, but it isn’t as cut and dry as it may first seem. Romero gets the ball rolling in the wrap-around segment, where we see young Billy (Stephen King’s real life son, Joe Hill) in tears after his abusive asshole of a dad (a smooth shaven Tom Atkins) throws out his beloved Creepshow comic. We know dad is going to get what’s coming to him when his son sees the festering, undead corpse of The Creep at his bedroom window and reacts as if his favorite uncle just stopped by for a visit, instead of screaming his head off like a normal child would. This is not the kid you want to mess with. Billy’s revenge will have to wait until we have flipped through all five stories in the comic book, though.

The first tale, Father’s Day, is the most quintessentially EC. A gold-digging family reunites every year to honor their wretched, controlling patriarch, who was done in years ago by his long suffering daughter, fittingly, on Father’s Day. The annual tradition goes off the rails when his shambling corpse escapes from the grave and tears through his descendants in a quest for his long denied Father’s Day cake. The moral is slightly hard to pin down here. Obviously, “Don’t murder Your Pops,” but there is more going on. Firstly, it’s hard not to sympathize with Bedelia (Viveca Lindfors), the patricidal daughter in question. She’s endured decades of torment from her sneering father and the old man killed her beloved suitor to keep her under his demanding thumb. Secondly, zombie dad kills Bedilia right off the bat. This should have started the vengeance that pulled him from the grave, yet he continues to bump off any irritating but technically innocent family member or servant that gets in his way to the kitchen. Forget justice, the decomposing bastard only wants his cake (note: his idea of what constitutes cake is wildly inaccurate). The best I can tell, the moral boils down to: “Those who benefit (even indirectly) from evil deeds will reap the consequences.” Alternatively, “Do not underestimate the allure of cake.”

You know what Henry? You’re a regular barnyard exhibit. Sheep’s eyes, chicken guts, piggy friends… and SHIT for BRAINS!

Wilma Northrup

If Father’s Day’s darkly humorous message was a little murky, we get a more challenging—and far goofier—quandary in The Loathsome Death of Jordy Virill (aka The Longest Stephen King Cameo Ever). King commits 100 percent as a down on his luck farmer (?) who retrieves the meteorite which crashed in his backyard with hopes of selling it “up’ the college.” Unfortunately, the mysterious celestial object carries a fast growing alien weed that quickly takes over Jordy’s property and body. Yes, King’s acting skills highlight that he should not quit writing, but I’ve always found his cornball antics charming, especially his vivid daydream scenes (with Jordy’s dad playing authority figure).

The most interesting thing about the story, though, is how it rather abruptly flips from broad comedy to become bleak as fuck. The sight of this lovable bumpkin turned into a walking moss patch, painfully pleading to God that he can at least pull off his own suicide successfully, tends to sour all of the chuckles rather quickly. It also gives a nihilistic touch to the green apocalypse hinted to be on the horizon. Pinning down the lesson in this morality tale is harder than all the rest, since the punishment seriously outweighs the crime. “Don’t let greed overcome caution” gives too much credit to someone already lacking in forethought, afterthought, or thought in general. Plus, his aspiration of making $200 to pay off a bank loan is practically saintly compared to the other miscreants in the film. I guess the ultimate takeaway here is “Don’t touch anything that just crashed from space, dummy!”

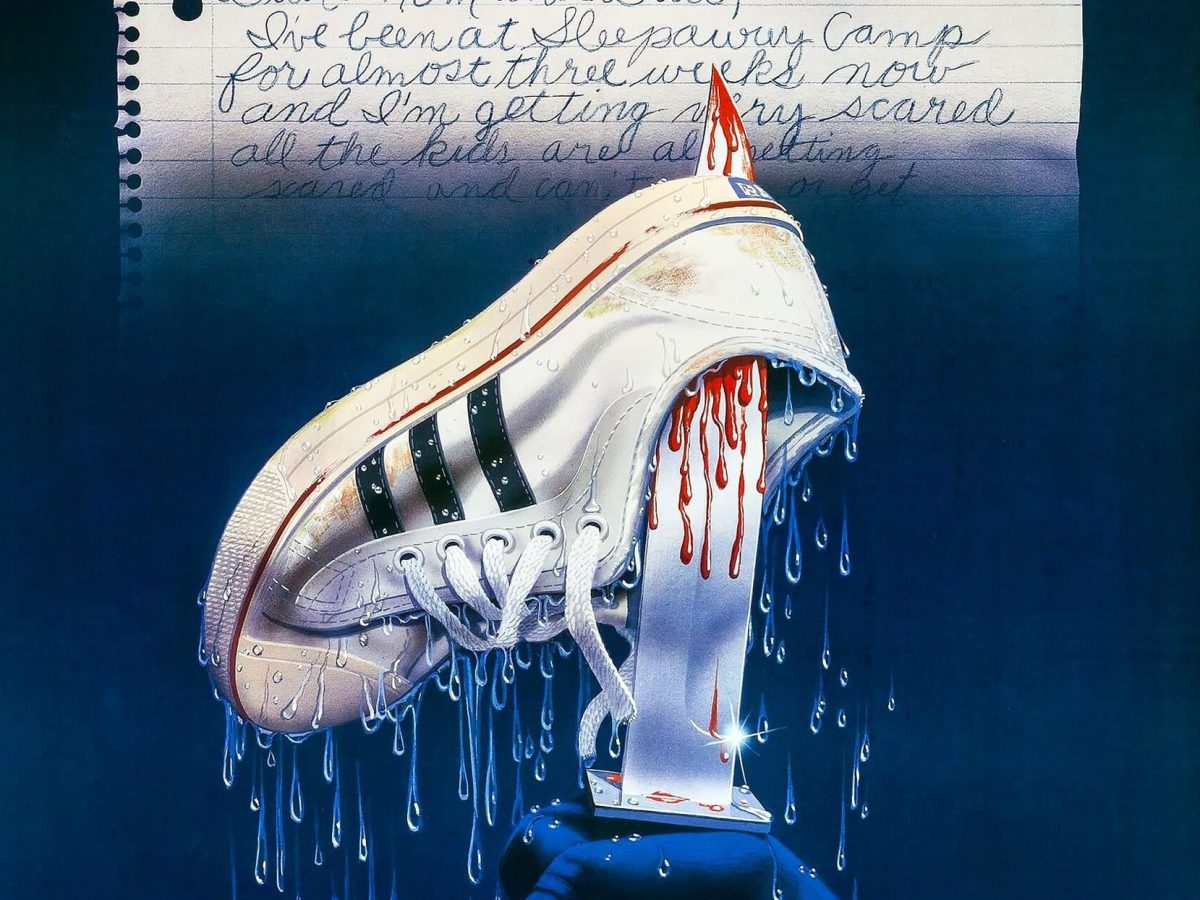

If the last two stories stood on questionable moral ground, Something To Tide You Over serves up some classic just desserts. Here we have Leslie Nielsen playing it deadly straight as the unhinged alpha male, Richard Vickers, taking sadistic revenge on his cheating wife and her lover until the tide turns and he gets a taste of his own medicine. With its wafer-thin plot, this segment stands squarely on Nielsen’s performance. Anyone expecting Det. Frank Drebin or Dr. Whats-his-face from Airplane is in for a shock because Richard is a stone cold son of a bitch. His affront at being cuckolded isn’t from any feeling of betrayal or heartbreak, it is solely proprietary. He cannot abide anyone taking something that belongs to him, including people. Watching his rival, Gary (Ted Danson, not challenging Nielsen in the acting department), buried up to his neck in sand and helpless as the tide inches closer, more than makes up for the loss of his wife. Not only does Gary have to watch his own doom slowly encroach, he is forced to see his lover go through the same thing on a live feed monitor. To top it off, Richard tapes the whole thing to enjoy again and again.

We know exactly where this tale is going when Gary, in between gulps of air, stares into the video camera and promises “I’ll get you, Richard.” The fact that Romero delays introducing Savini’s exquisitely detailed (and pruny) sea zombies is a testament to Nielsen’s devilish performance. It is a treat watching Richard merrily stroll through his house, pleased as punch with his live-on-tape executions, as the score plays an ominous keyboard variation of “Camp Town Races” (the only real levity in the segment). Where Gary’s slowly encroaching fate was agonizing, every teased out second of tension makes this jerk’s comeuppance all the more rewarding. Nielsen milks it down to the last frame. Consequently, there is no missing the moral here: “Don’t make aquatic snuff films.”

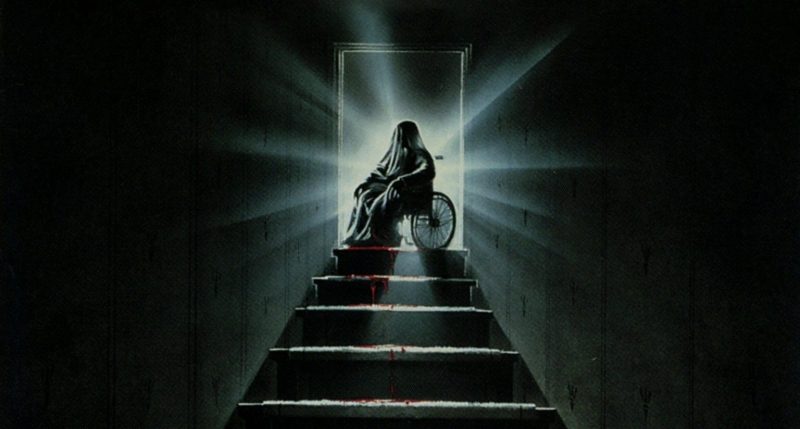

Hands-down, my favorite story in Creepshow is number four, The Crate. Coincidentally, it is also the one that flat out terrified me as a kid. I could skate through all the other segments by covering my eyes at a couple of potentially gory moments, but The Crate filled me with a pervasive feeling of unease through its entirety. It is also the darkest and most inappropriately hilarious piece, not to mention the most morally complicated. The Crate is a brilliant retelling of the Pandora’s Box fable, only instead of being filled with general evil, this one contains a nightmarish demon baboon that tears off your face. The titular, long-forgotten crate is accidentally discovered under the stairs of a Miskatonic-like University. After the box claims one foolish janitor and an overly curious grad student, distraught Professor Stanley (Fritz Weaver) calls his colleague, Henry Northrup (Hal Holbrook), for advice on dealing with the situation. Henry calmly and rationally decides on the most logical course of action: use this unexpected opportunity to finally bump off his foul-mouthed shrew of a wife, Wilma (living goddess, Adrienne Barbeau).

We want to see you, Richard. We dug a hole for you, Richard…

Harry

Fluffy, as Tom Savini lovingly refers to his creation, is one of the most terrifying monsters in cinema. Not just because of his maw-full of dagger-sized teeth (or his unnerving grin), but because of the unique nature of this beast. Unlike every other flesh-chomping fiend I can think of, he doesn’t come after you, you come to him. Even after being unsealed, Fluffy stays in, or close to, his century’s-old home. He doesn’t have to hunt for victims, curiosity inevitably and irresistibly does the hard work for him. This taps into one of our most primal—and predictably accurate—fears, that we are going get our own dumb asses killed by doing something stupid. This set up is aces all on its own, but adding Barbeau to the bloody cocktail elevates this segment to divine madness. Her performance as Henry’s boozy, caustic, ballbreaker of wife, Wilma (or as she says, “Just call me Billy”) is legendary. She’s Elizabeth Taylor from Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, but without the wit, class, or restraint. Wilma is so egregiously and amusingly wretched that Henry’s daydreams of publicly murdering her (to standing ovations) take on an almost Looney Toons absurdity. Somehow, Wilma is even more of an outlandish monster than Fluffy.

Romero’s most impressive feat is the way he juggles the discordant tones right up to the climax. Watching Henry mop-up the mess from Fluffy’s earlier victims (THERE IS SO MUCH BLOOD!) and carefully stage the crate for Wilma is nerve wracking. Watching Wilma drive all the way from home to the university still sipping the tall glass of whiskey-spiked milk she poured before Henry summoned her is hilarious. As soon as Henry commits and pushes his wife towards the crate, the tones crash together to make something new. The scene doesn’t go off like Henry’s daydreams. It’s messy and dangerous and vicious. Even when Henry yells the line that he’d probably been practising in his head all day (“Just tell him to call you Billy!”), it comes out shaky and hollow. Morality-wise, we are in seriously murky territory. Wilma was a terrible human being, but terrible enough to be fed to a monster? What’s worse, Henry seems to have gotten away with it, although the last shot suggests things might get messy again. Overall, the most fitting lesson is “Let sleeping crate demons lie,” but more specifically for Henry, “Divorce lawyers are less painful than prison or being digested.”

To offset The Crate’s moral grey area, Creepshow’s final tale, They’re Creeping Up On You, is as black and white as it gets. E.G. Marshall plays Upson Pratt, a heartless, rich old bastard who, after a lifetime of crushing the little guy to get ahead, finds karma skittering towards him on six legs. Like Stephen King’s segment, E.G. Marshall’s story is a one-man show. With its singular location, Pratt’s sterile white apartment, it could easily be a stage play (not that you would want to be in that audience). Aside from a quick and distorted appearance from Romero regular David Early as the most condescending building engineer ever, the rest of the cast are just voices over the telephone. Luckily, Marshall is significantly more skilled at delivering a monologue than King, so his powerful presence is all you really need. Plus a couple hundred thousand cockroaches.

Unlike its thematic twin, Something to Tide You Over, we never see the one event that precipitates the punishment. Pratt has spent decades ruining peoples’ lives and his balance is finally due, pushed over the line by the suicide of one of his competitors. We meet Pratt in his hermetically-sealed apartment, karmic retribution already in progress. He is in full Howard Hughes germaphobic recluse mode and bedevilled by his number one fear: cockroaches. After a few minutes of watching Pratt gleefully threaten, belittle, and torment his underlings over the phone, we’re on the roaches’ side. The more squashes, sprays, and vacuums—and the more he tries to rationalize away his sins—the more creepy crawlies appear. Yes, Pratt’s squirm inducing fate is a bit on the nose (and up the nose), but it couldn’t happen to a nicer guy. There is no mistaking the moral here, “If you are a piece of human garbage, be prepared for bugs.”

As for young Billy’s horror-hating father, he gets off easy, just a little pain in the neck courtesy of Billy’s mail-in voodoo doll. It’s a (mostly) innocent way to teach dad the most important moral of the movie: “Never shave your moustache unless you want trouble, Tom Atkins.”

Director: George A. Romero

Screenplay: Stephen King

Music: John Harrison

Cinematography: Michael Gornick

Editing: George A. Romero,

Pasquale Buba,

Paul Hirsch &

Michael Spolan