Halloween might have crowned Jamie Lee Curtis a scream queen, but the final girl roles that followed built a relationship with the audience that transcended the genre, reminding us of the magic that only movie stars can conjure

All movie stars are mysteries. Studio bosses like to crow that they “make” them, and Lord knows, plenty of stars are happy to credit their own outsized talent, will, and savvy. But the history of the movies is littered with actors who secure lead after lead only to muster a collective meh, and all those brilliant, devoted performers who have to settle for late-era character work or tiny movies to prove what they can do. The material, the director, and the limitless, Byzantine factors that shape any audience’s tastes, all have to line up perfectly, and for long-standing stars, line up repeatedly, and it’s nearly impossible to understand how that star ended up shining in the first place.

No wonder stars make the industry’s bean counters nervous. They were always there to tut-tut, but the wild-catting spirit that invented the medium, and would reappear periodically to revitalize it, has long been muffled by the big-money energy that dulls everything down. And now the stars, with a few exceptions, are shrunk to fit today’s screens. Which begs the question: so what? Isn’t it time to end the reign of these entitled make-believers? There’s still a village of sparklets around to juice the reboots, remakes, biopics, and vetted IP that fans crave.

What we lose when we lose movie stars is a certain intimacy, not with the actors, who now have to perform a kabuki dance of recognizable human behavior on social media. This leaves us watching an Oscar-nominated actress play with her salad like it’s Jenga, because see, she’s goofy! No, we’re losing the intimacy with their persona, the mixture of their own selves, their roles, and their craft that can delight or aggravate us, and yes, help us see ourselves onscreen. But this aggressive familiarity online leaves little room for the actor to build a persona, as such a thing feels phony after we watched them pull zucchini bread out of the oven or warble “Imagine” from their palatial estate during a global pandemic.

Jamie Lee Curtis is precisely the kind of actor that would struggle mightily to break through today, even as her actual path was hardly paved. At first glance, she’s no one’s idea of an irresistible force onscreen, but that’s precisely what she is. Her androgynous beauty and plucky, can-do spirit expanded our notion of what a starlet could be and do. Some suggest her real feat was finding the exit ramp out of the horror cellar, but it’s in the dark and gore that her stardom took root and flourished, in a way that standing atop the castle tower playing a damsel never could.

On paper, her origin story reads like the latest episode of Nepotism Baby! The daughter of two high-wattage stars, Janet Leigh and Tony Curtis, her literal godfather was Lew Wasserman, one of the most powerful executives in the history of show business. It’s worth pointing out that while folks gnash their teeth at any performer with contacts in the zip code of the industry, nepotism hardly seems a guarantee for success or longevity in the industry. Yet, we hardly muster any ire for the legacy admissions to Duke or Yale, who grow into corporate drones busy suppressing wages, burying their employers’ sins, and soaking up bloated salaries, all while regurgitating DEI jargon as if they brunch with Angela Davis. Those babies are floating through life in ways Chet Hanks never will.

The reality is that Jamie Lee Curtis came of age when both her parents’ stars were fading. Psycho made Janet Leigh an icon yet left her struggling to find work out of that iconic shower. Tony Curtis never found sure footing on the A list, despite his brilliance in the likes of The Sweet Smell of Success, Some Like It Hot, and The Boston Strangler. Although Jamie’s powerful connections no doubt played some part in her landing a contract at Universal in 1977 to play sexy faces on broadcast TV in the likes of The Love Boat and Buck Rogers. Everyone knows what happened next. John Carpenter and Debra Hill saw her potential and cast her in one of the most successful independent horror movies of all time, whose quality warranted the craze, built off transcendent framing and archetypal plotting, precisely the elements the gush of imitators ignored. There are rooms full of writing about what makes Halloween special, including the one-of-a-kind cocktail of vulnerability, decency, and grit that Curtis brought to her role, which for the most part invented the “Final Girl.”

The idea of the “Final Girl,” the lone survivor in a horror movie that slays the slasher/monster, was coined by the academic Carol Clover, in her book Men, Women and Chainsaws, but entered the pop lexicon in the flood of the meta-horror exercises of the 90s that strived to be the next Scream, rarely doing anything worthwhile with those ambitions. Fiction has done a far better job of reimagining the trope in the likes of Grady Hendrix’s Final Girls Support Group, Stephen Graham Jones’ My Heart is a Chainsaw, and Riley Sager’s Final Girls. All of these deconstruct the idea and replace it with living, breathing, complicated women, something that Jamie Lee Curtis was already busy doing in the horror movies that followed her big break.

There is a tradition of actresses showing up in a hit horror film and slipping out of the scream game to get respectable. Mia Farrow and Sissy Spacek made it, while Linda Blair and Heather Langenkamp did not. But in the wake of Halloween’s success, the offers failed to appear, given that the industry felt John Carpenter was the real star of that hit. So how did she graduate to other genres and manage to stick around for her latest renaissance in a fresh Halloween trilogy, prestige pop fare like Knives Out, and indie hits like Everything, Everywhere All At Once? In short, it’s a complicated mix of the horror projects themselves, her own skills, and how audiences consumed media in the eighties, a mix that’s clearly impossible to replicate again.

If there were any doubts that Jamie Lee Curtis struggled to land other roles, they can be dispelled by the fact that she needed Carpenter to cast her in his follow-up to Halloween. The movie concerns a small seaside town where a mysterious fog appears, containing homicidal spirits looking to avenge the crime that established the town. The Fog would be a troubled, frustrating experience for the director, mostly because controlling the title monster is pretty hard without CGI, and some legitimate story failures, with its grab bag of characters that work best in disaster pictures, and the ill-defined rules governing the fog.

Here, Curtis is out of high school, a restless bohemian hitching a ride with a local, played by Todd Atkins. She sleeps with him shortly after the ride, since at the time, in Carpenterville, Atkins was apparently sexual butterscotch. So out goes the Final Girl Virgin Principle. Laurie Strode radiated the ethos of a classic American girl, but her character here gets to lean into her tomboy sexiness, with echoes of Annie Hall, if Annie could change her own sparkplugs. Enjoying her fling, Curtis stays in town long enough to get drawn into the mystery behind the deaths the fog has already caused, and while she does her share of screaming, she’s good enough behind the wheel at one point, to save both Atkins and herself.

But her role here is clearly a supporting one, when the star is Adrienne Barbeau, playing a single mother and town DJ that gets wise to the threat early. But the posters featured Jamie Lee Curtis screaming as she tries to keep the door shut on the fog, acknowledging that she might be a draw now. But more importantly, the role expands the boundaries of her “good girl” persona while reaffirming her competence in the face of high-grade malevolence. The movie also featured her mom Janet Leigh, playing the town’s society matron in this, which should prove how much cache Leigh had when Curtis was trying to build her own career. The Fog didn’t help much. Although a financial hit, it didn’t match the performance of Halloween, and the reviews were mixed. Over the years, the consensus upgraded it to one of Carpenter’s stronger efforts, though the director remains a grouch about his failings here. But as this movie wrapped, the slasher boom inspired by Halloween was in full swing, with help from the Canadian tax code.

At the time, there was the Capital Cost Allowance (CCA) which amounted to a windfall of tax credits and loopholes for investors to bet on movies filmed in the country. And Halloween knock-offs were cheap to produce with gore and nudity promising to woo folks into the theater if the stars and story couldn’t. Known as the “slash for cash” era, the program helped wear out the genre’s welcome by financing so many of them, regardless of quality.

One such project caught the eye of Curtis, with a hefty 122-page script and a concept that seemed a marked departure from the slashers jamming up theaters already. She liked it enough to pursue the lead role on her own, as the rest of the cast needed to be Canadians to make the most out of the CCA. Finally, the producers were smart enough to recognize the value of getting Laurie Strode back in peril. Prom Night opens with a prank gone wrong, as a group of grade school kids play a sadistic version of hide and seek accurately called “Kill,” which ends with a young girl falling out of a window to her death. The movie then leaps forward several years, so the pranksters are now in high school, getting ready for prom and being hunted down by someone in a ski mask for their role in that young girl’s death. Curtis plays the victim’s sister, unaware she’s dating one of the pranksters.

Most of the movie is quite tame, choosing to roll out as a soapy high school whodunit with minimal blood and skin until the body count rises in the last half hour. But by making Curtis innocent of the opening prank, she’s never the target of the killer, eroding the stakes of the story. There are some deft directorial touches, but the picture is further compromised by the reshoots adding other potential suspects, including a recently released mental patient, and upping the bloodshed, dragging it into standard slasher territory. But Prom Night still did plenty to cement Curtis’ persona and add layers that made her all the more engaging to watch. She’s the most popular girl in school here, instead of the girl scout amongst her cooler, more liberated gal pals. When one of her meeker friends asks Curtis what she did when her boyfriend asked to sleep with her, she quips, “Who said I didn’t ask him?” The Final Girl trope often requires they don’t get lucky, but Curtis suggests that might not be so important. She even gets one hell of a solo disco dance scene that has somehow aged well, given her natural grace and commitment.

And when the killer finally crosses her path to kill her boyfriend, she manages to fight back, saving them both before realizing that her brother was the killer, a twist that my grandma could see coming without her reading glasses. Curtis is open at her disappointment with the final cut, as it felt like a Halloween re-tread, although its whodunit structure more closely resembles 1974’s Black Christmas, an influential Canadian slasher that’s been more frequently and faithfully imitated than Carpenter’s landmark, itself accused of mimicking the earlier picture. Despite being the least accomplished of her post-Halloween horror roles, Prom Night was a bona fide hit, racking up $15 million at the US box office, and earning more than any other Canadian horror movie that year. It was her Cocktail, a hit that can only be explained by the presence of a star. But it took place in the confines of a genre that was becoming more disreputable by the minute, with handwringing from parents, critics, and pundits who fretted teens were getting too much sex with their murder.

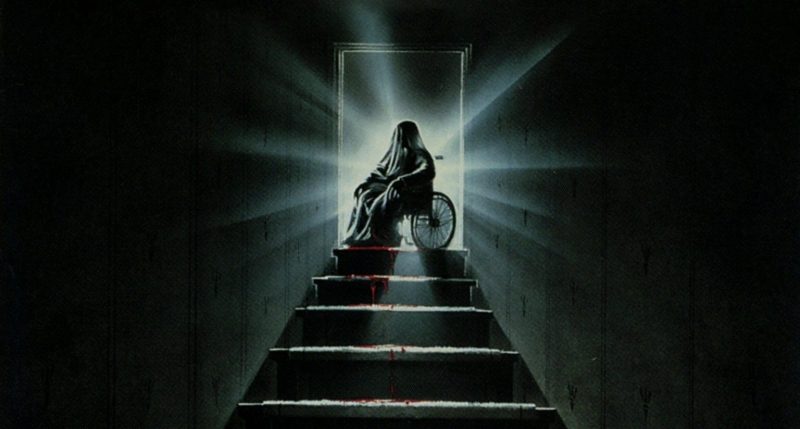

Studios didn’t let any of those concerns stop them, as Jamie’s next role was in 20th Century Fox’s first gamble on the genre, promising Halloween, but on a train. The premise was a group of college student book a train for a New Year’s Eve costume bash, only to find themselves murdered one by one. As another picture tapping the CCA, it had to be completed at breakneck speed by the end of the year to qualify for the program that was set to expire in January. But even under that pressure, this next project seemed like the most promising one yet.

Terror Train would be vastly more accomplished than Prom Night, for plenty of reasons, but starting with the DP. The legendary John Alcott wanted a break from Kubrick, for whom he shot Barry Lyndon and The Shining. Shooting dozens of set-ups a day sounded like a breath of fresh air after those marathons. The director was making his debut, but this was Roger Spottiswood, who had cut several of Peckinpah’s best movies, and landed the job provided he agreed to edit it as well. And Spottiswood’s involvement wooed the Oscar-winning icon and Peckinpah regular Ben Johnson on board as the train conductor and co-star.

Terror Train also opens with a prank, this time in college, as a frat boy med student (Hart Bochner) sets up Kenny, a nerdy pledge, to think he’s going to sleep with Jamie Lee Curtis, only to replace her with a cadaver. The shock drove the pledge mad, and now, three years later, he’s killing anyone involved on that train. The movie is smart enough to avoid pretending the killer is anyone but Kenny, though Kenny assumes the costume of his victims, leaving some guessing to be done along the way. Unlike Prom Night, Jamie Lee Curtis is culpable in the prank here. She lured Kenny to bed but was unaware the prank involved a dead body. Curtis does a lovely job of that slow realization, nervous at the start, maybe a little excited to get the gag right, only to be horrified once she sees that a cadaver was the punchline. It’s all registered in her face, not the script. Faces are key in slasher films since these movies rarely have the time or inclination for character development. So much of our emotional connection in slashers is rooted in how these actors’ faces gauge the threat, realize the horror, and steel themselves for a showdown. These movies require a lot more of their stars than just lungs.

Alcott’s work is stunning of course, with the train’s heaving, coal-black bosom leaving the station draped in blue fog to set a high Gothic tone, even if the movie never matches that. Alcott ended up rewiring the whole train with mini bulbs on a complex dimming system as they didn’t have room to hang traditional lights, which helped the costume party’s colors pop. Spottiswood stages the murders with real tension and like a great editor, maintains a delicious pace, brisk without barreling. As one of the few performers over 25 on set, Ben Johnson has the good nature here of a grandpa invited up to a treehouse séance. Curtis has a lovely rapport with him, as they both comprehend the nightmare before the rest of the party.

Curtis maintains her persona here as the kind-hearted popular girl, who was rightly horrified by the prank and is given underdog vibes, with her having to work her way through school, unlike so many of her friends. Gone is any trace of Laurie Strode’s fragility, as she’s keen to tell her boyfriend off and read the riot act to Hart Bochner’s horny frat douche. Bochner’s performance here does more than hint at his most famous role as Harry Ellis, smarm incarnate, in Die Hard. She’s no virgin here either. She might not be ripping her shirt off, but she carries herself with a sexual confidence that can’t be denied. She ably flirts with David Copperfield, who has a cameo as the party’s magician, exhibiting a creepy anti-charisma that works on something called Terror Train. She might be decent, but she’s no prude. And she’s still terrified, exhibiting vulnerability in equal measure with her daring. She prevails in her confrontation with Kenny, but the battle is drawn out here, giving her more time to prove her mettle. Unfortunately, Terror Train failed to prevail at the box office, with its $8 million box office falling well below studio expectations, and the harsh critical reception seemed more rooted in exhaustion with slashers than any failings of this entry. Curtis herself was eager for some daylight between herself and the slasher industrial complex, and the next role felt like a bridge to better parts.

Road Games is the best of her post-Halloween horror films, an Australian Rear Window set on the open road, with Stacy Keach playing a nonconformist trucker who’s convinced there’s a killer picking up hitchhikers and scattering their body parts across the sunburnt outback. Directed by Carpenter’s USC classmate Richard Franklin, it’s a crackerjack thriller with great laughs and terrific chemistry between Keach and Curtis, playing a diplomat’s daughter who’s hitchhiking for fun. She’s worldly and whip-smart here, but this, like The Fog, was a supporting role. She doesn’t show up until thirty minutes in, and after some time connecting with Keach, finds herself off-camera, trapped in the killer’s van. Franklin was hoping to use her stardom as misdirection, knowing that audiences wouldn’t expect her to be captured, let alone killed, so early. He’d later regret not keeping Curtis on screen for longer, with Keach and her remaking their own African Queen together. Curtis is eventually saved, but when she’s finally freed, she’s only pissed that Keach didn’t save her sooner. It’s exactly the kind of gruff grace we’d come to expect.

Road Games flopped hard at the box office. In hindsight, this movie was never going to land in the early eighties. With a Hitchcock plot and Howard Hawks characters, it was a nostalgia piece for things nobody was missing… yet. Franklin’s chops here did get him the job directing Psycho II, which made some bank but was eventually acknowledged as a competent effort at an impossible task. Curtis was already on to her next role, one that in its miscasting helped further define who she was. Longing for a post-slasher career, Jamie Lee Curtis pulled out all the stops to land the lead role in the TV movie Death of a Centerfold: The Dorothy Stratten Story. It was a cash grab production, pursued only months after Stratten, the Playboy Playmate of the Year, was found murdered by her estranged husband. Hugh Hefner and Stratton’s boyfriend at the time of her death, the director Peter Bogdonavich, wanted no part in this. But for Curtis, this felt like a chance to break out of the genre that was a mixed blessing at best.

Unfortunately, Curtis as Stratton is hard to watch. Stratton was an insecure, deeply troubled young woman who found herself trapped in an abusive relationship she couldn’t escape. And while Curtis can play insecure, there’s a tragic passiveness to Stratton that simply is impossible to believe from her. The most shocking moment was Curtis with a black eye, as we’ve rarely seen her harmed without fighting back. The production values only further sink this, with the canned score and flimsy sets of some no-name cop show of the era. A relative hit for ABC, it has aged terribly. Bob Fosse would close out his film directing career with his own version of the tale called Star 80, with Mariel Hemingway and Eric Roberts in the leads. It was a slice of lurid gristle that properly captured the tragedy, which turned out to be something absolutely no one wanted.

Curtis would return to Haddonfield in Halloween II, primarily out of loyalty to Debra Hill and John Carpenter. It made a tidy profit but was gauged as a disappointment, in no small part because Laurie Strode was sidelined in the hospital for most of the picture as Michael Myers slaughtered the rest of the cast. It’s a choice repeated in the current trilogy as if it was something we missed. It was not. After this, she did finally manage to break out of the genre, with the one-two punch of Roger Corman’s rare non-schlock picture Love Letters, and the studio comedy that freed her for good, Trading Places, directed by horror fan and renowned asshole John Landis. Both involved onscreen nudity, something that Curtis avoided up to this point, and it should be noted that while she was a “Scream Queen” in slashers, her nickname in mainstream fare at the time was “The Body.” But that overlooks what Trading Places actually gave her persona, which was a natural sense of humor that anyone who worked with her previously was already well aware of.

And as her career progressed, her chops as a comedienne became undeniable, reaching their zenith in A Fish Called Wanda, and the remake of Freaky Friday, a sleeper hit that earned its box office off her incredible work there. She’d remain a fixture in the industry, surviving strings of flops and misguided efforts. And her years besting homicidal maniacs complicated efforts to reduce her to one-dimensional hookers, girlfriends, and moms. All those horror flicks left her with an edge that couldn’t be sanded down. Some filmmakers were even canny enough to use it. Kathryn Bigelow deployed it to great effect in Blue Steel, where Curtis plays a rookie cop fending off the terrifying sexual attention of Ron Silver, that sentient bottle of Drakkar Noir. The two women didn’t see eye to eye on set, but Curtis would later be deeply grateful for one of the best roles of her career, even if it flopped at the box office.

In fact, it’s hard not to wonder why Curtis stayed relevant despite so many disappointments and outright failures. The Fog and Prom Night were financial successes, but Terror Train was not, and most forgot Road Games even existed. But this was also the VHS era, which obscured the box office failures of so many movies, given how often they got a second chance to make a first impression. Slashers and other horror fare were a video store goldmine, as teens and twentysomethings rented the likes of Prom Night, Terror Train, and of course Halloween, over and over again. Broadcast networks no longer dictated what movies came home, and VHS versions rarely censored content, despite Blockbuster’s puritanical efforts. And given that each movie cost a few bucks to rent, people had to choose what titles to take home, rather than opening the spigot of a streaming platform and wading through endless posters, which ends up making them all seem disposable.

In the VHS era, movies started to feel more like music. Folks brought the movies home like albums, where these pictures became part of their lives. The onscreen creaks and screams are taking place inside their house, granting a greater intimacy with these stars. And then the big screen took on the role of the concert, letting them see these stars in their proper glory. This was back when home entertainment was seen as something that stoked appetites for going to the theater. The Bourne Identity might be the last underperforming movie that found its footing at home and translated that into box office gold for its subsequent sequels (no doubt helped because Paul Greengrass directed them into delirious crunch-fests that redefined action movies for years).

So Jamie Lee Curtis was busy evading killers in our own homes for years. She felt like part of the pop culture firmament, not to be dislodged by any one movie. It made perfect sense that she’d be Arnold’s wife in True Lies or the mom in Freaky Friday. We were glad to see her. She never disavowed her slasher roles, reprising her role as Laurie Strode in the underwhelming Dimension sequels and returning to David Gordon Green’s big-budget sequel trilogy, giving the character the wear and tear of someone who was hunted by a supernaturally resilient killer. And these are legitimate blockbusters, dwarfing the performance of the rest of her filmography, save for her trip with James Cameron, even if they center modern obsessions around trauma so relentlessly it feels best suited to a drinking game.

However, there’s no way to argue that she’s on the A-list, but she’s a star, and someone we’ve come to have a great affection for, precisely because she was allowed to be the consistent force in several stories, as opposed to peak TV that leaves us watching John Hamm or James Gandolfini play the same characters for hours upon hours. It’s heartbreaking to know we won’t get another Enough Said from Gandolfini, and hopes are slim that Hamm’s terrific turn as Fletch will become a franchise. There’s so much we lose when the persona doesn’t get a chance to grow over multiple projects. And this is about the persona, not the personality. We have personalities now a-plenty, and I appreciate we’re about fifteen years into the Attention Wars era of pop culture, where online followings can comfort producers into casting someone new. But when the industry outsources the star-making process to social media, they’re sapping any intrigue a star can muster. Intimacy with these personalities as people is no way to build intimacy with them as performers.

But that’s what they are. And it’s deeply aggravating that precisely when the industry grows more inclusive of all races and sexual orientations, it also demands that this new wave of stars be vulnerable, accessible, and saintly in equal measure to warrant their face time. A situation that’s deeply infuriating because movie stars owe us nothing more than their performance. Anything more should be left to their friends, families, and the authorities to sort out. The problem for bean counters and online mobs is that movie stars are such an intrinsic part of the medium, they can’t be wished away. Their personas often get richer as they get older, right alongside us, and once they make us swoon in one way or another, we’re eager to fall again. Gandolf, Batman, or James Bond don’t age like the people who play them do, and over the long term, it’s alienating when we can’t carry the same performers with us, say when the action hero ends up the character actor that brings all their onscreen history to their cameo. The actors aren’t part of the fabric of our lives, but their personas are, and those bean counters should understand a lot of folks are willing to lay out some serious bread to keep the old relationships up, and even start a few new ones.

But that takes investing in stories, not merely existing IP, and letting actors shuffle through low-budget excursions and disappointments, with an eye for those performers that shine a little brighter no matter where they are. They’ll be mistakes, sure, but they’ll be a Jamie Lee Curtis in the bunch. Her path to stardom can’t be repeated, but for those of us who watched her play the Final Girl over and over again, it’s not quite a riddle how she’s managed to survive this long. Long live Jamie Lee Curtis, and whoever’s the next oddball that wins us over by surviving the final reel.