Dissecting Joseph Ruben’s scathing satire on Reagan’s family values

On a quiet, leafy suburb we enter a house, a white picket fence monument to Reagan’s America. Inside, a man stands bloodied yet strangely serene, staring at his reflection in a mirror, staring as if that reflection belongs to someone else entirely. The man washes, trims his hair, removes the gruff to reveal a baby-smooth veneer ― a complete transformation. Packing a suitcase, he walks across the hallway, a collage of a smiling family decorating the walls. He even stops to pick up a child’s toy, neatly placing it back in the family chest. Order restored.

As the man nears the front door, we hear a phone bleating alarmingly, and the man stoops down, calmly placing it back on the receiver. Beyond him, a family lie slaughtered, sprawled across the living room furniture like bloodied rags. Unperturbed, the man calmly leaves the residence in broad daylight, whistling without a care as he strolls into the neat suburban wilderness. There’s no panic on his part, no sense of urgency, and the smiling folks of middle America are none the wiser. Sometimes appearances really are everything.

The opening moments of Joseph Ruben’s biting satire on 80s conservatism, The Stepfather, are, even to this day, pretty startling, and very much redolent of another notorious 80s shocker. In 1986, rookie director John McNaughton was approached by a Chicago home video executive who was eager to cash in on the low-budget slasher craze, expecting a money-spinning slice of exploitation for his $110,000 outlay. What he got instead was a painfully authentic docudrama chronicling the everyday exploits of a deadpan serial killer that caused such a stir it was immediately banned, festering in commercial purgatory for almost a half decade.

Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer was loosely based on the crimes of real-life serial killer Henry Lee Lucas, a drifter convicted of 11 murders who later claimed to have killed over a hundred people. Though his credibility has been brought into question, he remained publicized as America’s most prolific serial killer, and is even guilty of committing matricide. In the movie, ‘Henry’ drifts from town to town, hooking up with real-life accomplice Ottis Toole as the two set off on a warpath of non-discriminatory murder. Scenes of home invasion, captured by the pair on video, are still hard to stomach thanks in large part to the fearsome lead performance of a young Michael Rooker, who describes murder as “always the same and always different” with a chilling sense of dispassion that very few possess.

Though loosely based on the life of mass murderer John List, a long-time fugitive who killed his wife, mother, and three children at their home in Westfield, New Jersey before assuming a new identity, remarrying, and eluding justice for close to eighteen years, The Stepfather is much more humorous beyond its infamous opening scene. Unlike List, Jerry goes on to kill again, and though our protagonist is a far cry from Rooker’s bottomless proponent for human disposal, like McNaughton’s Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, the film was marketed as an all-out slasher when in fact it was something else entirely. The Stepfather was initially presented as a psychological thriller until a lukewarm response altered distributor New Century’s plans. Sometimes you have to give audiences what they want, even if they’re likely to leave theatres feeling cheated.

Father knows best.

Jerry Blake

If you’re like me, you won’t feel cheated by The Stepfather. Chances are you’ll feel like you’ve gotten more than you bargained for. Like ‘Henry’, the film benefits from a superlative lead performance from TV stalwart Terry O’Quinn, who absolutely relishes in the role of a white, middle class American struggling to uphold unrealistic moral values. The film was made while president Ronald Reagan, himself embroiled in political and sociopolitical subterfuge that included illegal arms deals and the hugely hypocritical ‘War on Drugs’, was giving pretty little speeches about ‘a return to traditional American values’, the kind of flag-waving fantasies that exist only as forms of social control. Some, like O’Quinn’s deliciously insane Jerry Blake/Henry Morrison/Bill Hodgkins, buy into such sentiments wholeheartedly, defying the imperfections innate in humanity with a butcher’s relish.

There’s a telling moment when the distrusting daughter of Jerry’s latest conquest confides in a friend, explaining how she doesn’t exactly trust her new father figure, a relative stranger so genial, supportive and selfless he could only be a disassociated murderer skipping glibly from family to family. Jerry, a realtor who claims to be, “selling the American Dream”, is intent on forging the perfect American household, a myth that pushes him to the brink time and time again. In stepdaughter Stephanie’s own words, living with Jerry is “like living with Ward Cleaver,” the fictional lead of picture perfect 50s sitcom Leave It to Beaver. In reality, 80s sitcoms weren’t much different. There were enforced tweaks, like the handling of ethnic characters in an increasingly multicultural society, but they generally painted American families in an unrealistic light, promoting high moral values while burying the imperfections of the modern family unit, a notion that Jerry singularly personifies. In 1992, Reagan’s presidential successor George H. W. Bush gave a famous speech at the National Republican Convention that urged American families to be “more like The Waltons and less like The Simpsons.” Talk about self-denial!

Stephanie is played by former actress Jill Schoelen, who would add her name to the scream queen pantheon after starring in a succession of horror movies that include Wes Craven’s Chiller, cult 90s slasher Popcorn and the belated, made-for-television psychological horror sequel When a Stranger Calls Back. Schoelen is perhaps most famous for her brief engagement to a young Brad Pitt, the two meeting on the set of black comedy Cutting Class having fallen head over heels in love, which in Hollywood terms amounts to a three-month fling. That fling ended after Schoelen, who also dated a young Keanu Reeves, fell for the director of her next film, Halloween IV‘s Dwight H. Little, while shooting 1989’s The Phantom of the Opera in Budapest. As Pitt would explain, “[Schoelen] called me up in Los Angeles and was crying on the phone. She was lonely and there was a huge drama. At this point I had $800 to my name and I spent $600 of it getting a ticket from Los Angeles to Hungary to see her. I got there, went straight to the set where she was filming and that night we went out to dinner. She told me that she had fallen in love with the director of the film. I was so shocked I said, ‘I’m outta here.’ “ What a heartbreaker!

Ironically, ‘The Stepfather’, under a plethora of guises, seems to have good intentions, but masking his flagrant insanity proves something of a stumbling block. When O’Quinn absolutely loses his shit within the sanctum of his handyman basement, flying into fits of rage that border on self-harm but ultimately reveal themselves in the harm of others, it’s genuinely unsettling, but you can totally relate to the character’s struggles to keep a lid on things. This is a man, like millions more out there, who smiles unconditionally for a living, whose social circle stretches no further than colleagues and clients who share generic anecdotes and laugh on command, a man whose every word and action is calculated to conform to a fabricated image of middle class America.

Jerry falls into the ‘mission-oriented’ category of serial killer, a pragmatist who sets out to improve the world based on his own standards. Such killers target specific groups, in this case the crumbling nuclear family, Jerry installing himself as the absent patriarch before acting as judge, jury and executioner when things don’t go exactly to plan. Mission-oriented serial killers, who justify their acts as being necessary for the good of society, typically target prostitutes or the homeless, men or women with no family ties who wouldn’t be missed, though such instances have grown increasingly rare. In fact, the decline of the serial killer, a phenomenon that peaked between 1970 and 1990, has been dramatic in recent years, mass murderers or ‘spree killers’ taking their place. The distinction between the two may seem tenuous, but like Jerry Blake a serial killer is defined as “a person who kills more than one victim in more than one location in a very short period of time,” while a mass murderer is, “someone who kills two or more victims over a short period of time without a cooling-off period.”

The reasons for this shift, and the decline of serial killers in general, are technological, sociological and scientific. Environment and behaviour are key. Traditions such as hitchhiking or letting your children play freely are very much a thing of the past, people more aware of the threat that certain members of society pose. Surveillance technology and mobile phones have also played a part for obvious reasons, the early detection and reforming of potential serial killers something society has become more skilled at. We’ve also made incredible advancements in the field of forensic science, the use of genetic techniques seriously impacting the potential for serial murder. In short, victims have become scarce for serial predators in the 21st century, but for a while they seemed to be everywhere.

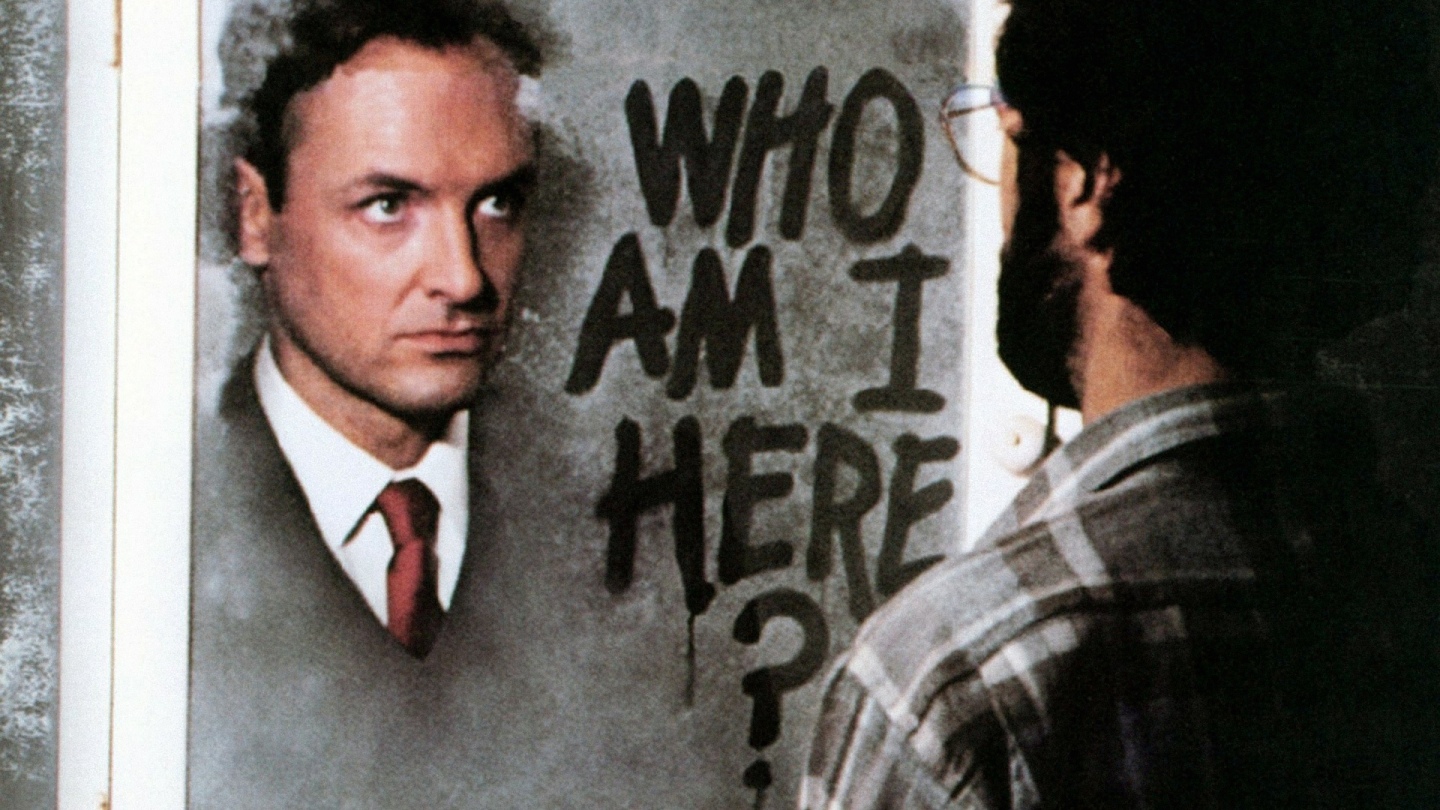

Wait a minute, who am I here?

Jerry Blake

This was especially true during the 80s, a decade in which serial killers were very much a part of the western consciousness, the likes of Jerry Blake blurring the lines between outward civility and pent-up insanity. Audiences no longer feared the likes of Frankenstein’s monster and Nosferatu, the world’s real villains garbed in everyday mundanity. The fact that a long-time acquaintance, friend or even family member could be a psycho in disguise left a generation in denial. Could there really be a remorseless killer living in your very own back yard, the kind you’d invited into your home and shared tea with, who even stopped to talk to your kids on occasion, all smiles and sound advice? It’s one thing to be scared of an apparent threat, but it’s when you’re unable to identify that threat that things become truly problematic.

The idea that a seemingly wholesome citizen could pull off such atrocities is not as far-fetched as The Stepfather sometimes suggests. Prior to his death on January 24, 1989, infamous American serial killer Theodore Robert Bundy finally admitted to the murder of 30 women across seven different states between 1974 and 1978, though the total is believed to be many more. Bundy denied such abhorrent acts until his execution via electric chair, only revealing information as a way to buy more time. Previously, Bundy spoke of his crimes in the third person, as if someone else was responsible, something glimpsed in the scenery-chewing exploits of a jaw-droppingly delusional Jerry Blake. More worryingly, Bundy and Blake were well educated and extremely charming without a single documented crime to their names, both projecting an image that belied their cruel and calculated nature. The narcissistic Bundy, all smiles and bravado, even won himself an army of fans for his misdeeds, becoming a precursor to the modern-day reality TV star. If that isn’t proof our capacity for self-delusion, I don’t know what is.

Like Jerry, Bundy also had an uncanny knack for going undetected, escaping from prison on two separate occasions and committing crimes on the run for weeks on end. Besides being devilishly ingenious, he just had one of those chameleon faces, the kind that could make him look like several different people from several different angles. All he had to do was shave, cut his hair, change his glasses, and he could wander America freely, a person who had dominated news programs for months on end. This was a man suspected of killing more than a hundred women over a period of more than a decade, a person so adept at subterfuge he was embraced by members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, some of whom believed in Bundy’s innocence until the bitter end. Like Blake, Bundy would target an area until things got a little too close for comfort. At that point he’d simply move on, meet new friends and find a new job in an entirely different state, all of it predicated on an unquenchable desire to kill.

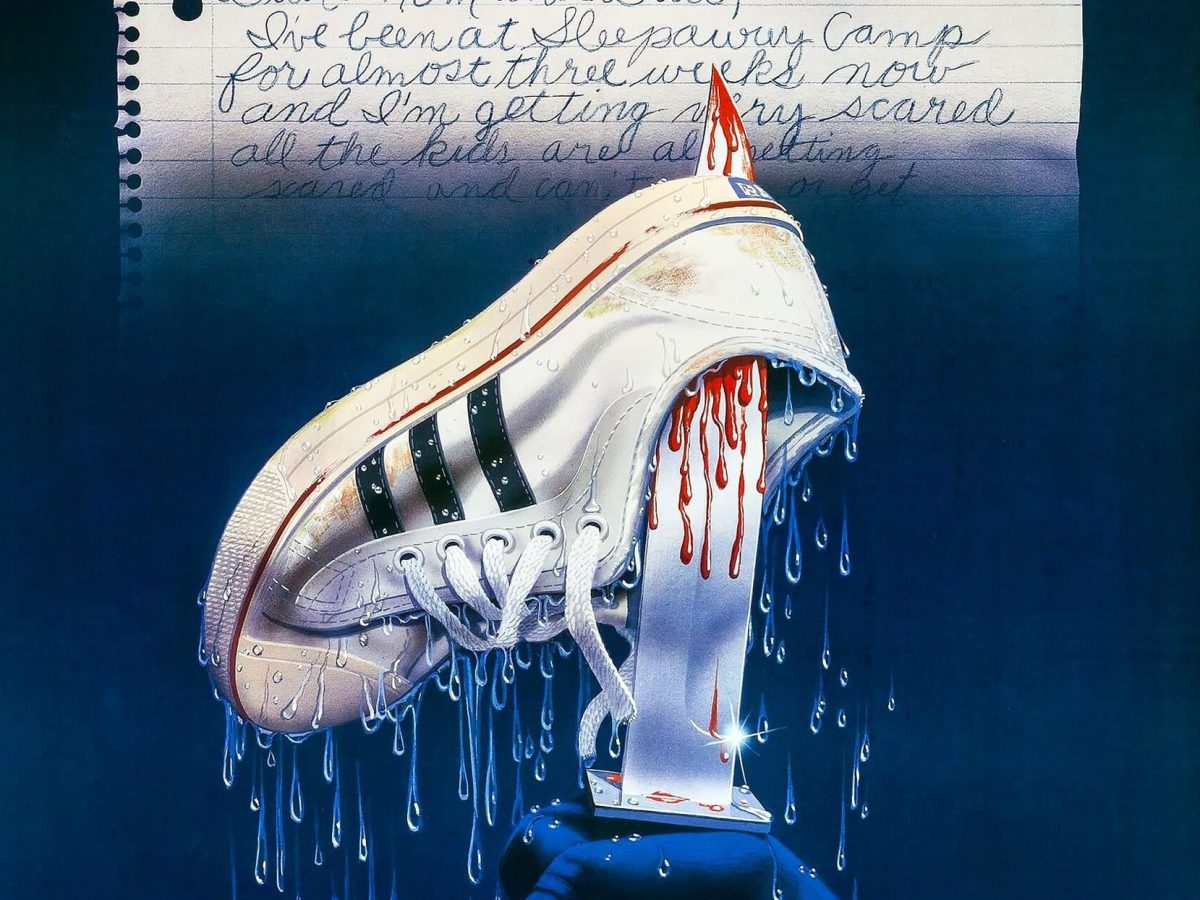

Bundy’s exploits may seem unlikely from a modern perspective, but this was before DNA, CCTV and the Internet. If you were an aspiring serial killer and the cops had next to nothing on you, you could just up sticks and leave town, safe in knowledge that you’d both be starting from scratch. It’s not like the police had a foolproof nationwide network. In fact, there was something of a rivalry between cops from different jurisdictions, a quasi-nationalistic code that prevented them from sharing information. Such pettiness seriously impacted the attempted capture of Richard ‘The Night Stalker’ Ramirez, a serial rapist and home invasion killer who ran roughshod over Greater Los Angeles and the San Francisco Bay Area between June ’84 and August ’85, drawing direct comparisons with McNaughton’s ‘Henry’. It’s no wonder that the slasher picture, taking its narrative cue from the suburban killers of the day, would become such an enemy of Reagan’s America and Thatcher’s Britain, leading to the 1984 Video Recordings Act and the outright banning of 72 movies dubbed the ‘Video Nasties’ in the UK.

Entertainment has always been a convenient pawn in the fight for civil liberties, but there’s no doubting the genre’s potential for copycat killers, who, like millions more embracing the escapist thrills of the day, were exposed to unprecedented depictions of rape, torture and mutilation that had miscreants licking their lips in the shady recesses of theatres across America. While Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, a film so palpable it wowed and worried critics caught between admiration and revulsion, was stuck in distribution limbo, controversial festive slasher Silent Night, Deadly Night, with help from high-profile critics and staunch sub-genre detractors Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert, proved the the straw that broke the reindeer’s back for concerned parents across the nation, the movie quickly pulled from theatres after a blistering opening weekend that trumped Wes Craven’s original A Nightmare on Elm Street. Bob Clark’s slasher innovator Black Christmas even had its television premiere delayed after Bundy, in an act that mirrored the movie’s plot, broke into FSU’s Chi Omega sorority house and brutally attacked four students, killing two and leaving two for dead. Had Bundy embraced the authentic horrors of Clark’s film prior to committing such acts? It’s certainly worth considering.

The Stepfather isn’t a slasher in the traditional sense, but it could easily have been lumped-in with the genre’s most notorious films had it been released just a few years prior, especially as it directly attacks the conservative values against which the genre was held. Instead, it was released after the likes of Jason Voorhees had ditched the dead-eyed killer motif for self-aware horror shenanigans, relying on the supernatural elements of yore and a self-aware humour that transformed the era’s villains into pop culture antiheroes. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre‘s Leatherface, inspired by a plethora of serial killers and the figurative masks we wear, would also take the overtly comical route in Hooper’s batshit follow-up The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, which went as far as ironically ripping off the promotional poster for John Hughes’ brat pack smash The Breakfast Club, a vulgar indicator of how desensitised society had become in a post-Watergate climate. Jerry is cut from a similarly whimsical cloth, delivering a series of tongue-in-cheek quips that tapped into the mainstream appeal of characters like the evolving Fred Krueger, but unlike those other films it managed to retain an element of social critique that exposed the hypocrisy of the sub-genre’s most staunch detractors.

If The Stepfather had been made during the slasher’s golden age, we may have been discussing a very different movie. The potential is there for a dark and intense character study, one that, like ‘Henry’ before it, may have fallen into a commercial void and struggled to find an audience at a time when horror was exploring a very different path, falling into a mostly uninspired period of oversaturation by the early 90s . The opening moments certainly capture the slasher’s nihilistic glory days, the film’s furious finale plenty bloody for the time, but director Joseph Ruben abandons the nihilism early on, O’Quinn’s Jerry tapping into the mainstream trends of Krueger and co with a series of delicious puns that laid the groundwork for a horror franchise with our killer as the wisecracking protagonist.

This punk was trying to rape our daughter.

Jerry Blake

Once Jerry’s mask of sanity slips, O’Quinn revels in the theatricality of it all, warning an already dead victim to “buckle up for safety” before sending him careening off a cliffside and drinking-in the subsequent explosion like a man temporarily freed from demonic slavery. His insane overreactions smack of Reagan’s middle class America, a demographic spoon-fed stories of drug addicts and ethnic races corrupting their children, a generation urged to put bigger bars on their windows as faceless killers wandered freely. When Stephanie’s damp squib of a love interest harmlessly kisses her on her doorstep, Jerry immediately sees red and accuses the boy of trying to rape his daughter. When Stephanie’s concerned psychiatrist goes undercover at a viewing, Jerry takes an immediate dislike to his bachelor pretence, explaining that such a house should belong to a family, and when the doctor goes a step further, dismissing the notion of family as “all that crap”, all bets are off. At one point, a blood-spattered Jerry, having just slain his latest victim, stops to embrace the family puppy, lavishing in the poor fellow’s unconditional love.

Crucially, there’s something of a tragic quality to Jerry, a poster boy for Reaganite America so consumed by self-denial that everything becomes abstract. Amid the buttoned-down madness, each smiling face begins to meld into the next, each person an illusory fragment of a dozen recycled lifetimes. While spinning yarns about his perfect family to a customer’s young daughter, he mistakenly refers to his own child using two different names, his face a delusional cloud of serenity. When he accidentally refers to himself as someone else entirely, his partner suddenly suspicious, Jerry stops to ask, “Who am I here?”, and immediately the game is up, the entire façade unravelling in violent acts of self-cleansing that will never be enough to assuage. It’s all so desperate and futile. Jerry speaks to conformity and conditioning, which is why kids like Stephanie see him coming from a mile away. She’s too young to fully comprehend the standards we’re expected to live up to, how as adults deception and fakery become everyday practice. The most worrying notion is how easily people are fooled, and how we in turn fool ourselves. As adults we look for the kind eyes, the desirable job, the respectable appearance, but the devil doesn’t wear a moustache and carry a pitchfork. He smiles as he helps you with your groceries. He’s everywhere and he’s nowhere.

The Stepfather is far from perfect. It is plagued by unintentional melodrama or plain bad acting on occasion, Jerry’s latest spouse, Shelley Hack from Charlie’s Angels, well cast but severely underutilized as the film dips in and out of underwhelming thriller territory. The film’s biggest drawback is a flimsy sub-narrative involving a relative of Jerry’s previous victims, a character who stumbles headlong into one stupid development after another on an unyielding but wholly fruitless quest to catch his sister’s killer. The character is plodding and vacuous to the point of having no impact on the screenplay whatsoever, as are those who cross his path prior to the film’s finale. When the man finally tracks Jerry down, he fumbles for his pistol so uselessly he’s knifed to death on sight, immediately confirming our worst fears: that sections of the film are lazily developed padding with no real purpose. Take O’Quinn out of the picture and you’re not left with very much.

Thankfully, O’Quinn is front and centre for the most part. The self-aware act works too; better than most, in fact. While the likes of Fred Krueger became aimless figureheads for youth-oriented marketing, The Stepfather‘s Jerry Blake is a case of ‘it’s funny because it’s true’. In the tradition of characters such as American Psycho‘s Patrick Bateman and Falling Down‘s William “D-Fens” Foster, we can relate despite a level of violence that is completely at odds with our sensibilities. As a self-aware species humanity is prone to self-loathing. We’re taught to resent and deny our imperfections through ethical and religious codes that can be unrealistic, the kind that generally do more harm than good. In reality, we’re as prone to kindness as we are wickedness, a combination of nature and nurture determining our paths in a world of complex half-shades. Though Jerry’s past is sketchy, he reveals that he had a tough, conservative upbringing, raised on the kind of moral values so detached from reality that every person, regardless of how kind or polite or congenial, becomes fatally flawed, yet another victim on his unattainable quest for moral perfection.

Director: Joseph Ruben

Screenplay: Donald E. Westlake

Music: Patrick Moraz

Cinematography: John W. Lindley

Editing: George Bowers

Excellent essay on “The Stepfather” Edison, and I also like the social commentary here.

I was a little kid in the Reagan era, and I remember vividly the “War on Drugs” campaign (It seems every First Lady had a life cause: Betty Ford’s was rehab, Rosalynn Carter’s was homelessness/mental health, & Nancy Regan was on drugs). I was in 3rd grade (I failed 2nd grade so I should’ve been in 4th; I’m #1) when “The Choice For Me is Drug-Free” stickers were passed out; being a wise guy, I crossed out the “R” in “Free”. The Iran-Contra scandal was really something too: that poor Oliver North (talk about doing an “Ollie”). This is why we don’t trust politicians though: what they say is either too idealistic or unrealistic. It’s easy to talk a good game (“politicians make the grade, speechwriters pave the way”), much tougher to play one.

That’s a good reason why a character like Jerry Blake is viable to me: for someone to believe in all that rhetoric, he must not be playing with all his aces & spades (he does, however, tool around in the basement).

I love the inclusion of the on-set photo of the Blake family; the family that bleeds together, stays together.

Yeah, I guess if we combine to chameleon elements of Ted Bundy with John List’s spree on his family, we get what closely represents Jerry Blake. Actually, Bundy’s murderous track record may explain why George H.W. Bush referenced “The Simpsons” instead of the Bundy family from “Married…with Children” (which I feel is a much more typical & realistic interpretation of family than “The Waltons”, as the Bundy’s are a dysfunctional family that loves each other).

I really do like this film though, and the smoldering insanity portrayed by Terry O’Quinn’s Blake, which I felt was scarier than the actual violent events. I think striving for perfection is important, but realizing that it’s unattainable is even more important.

I agree with you though, the subplot with the relative never really worked for me either, as those scenes to me felt like they were coming from a different film entirely (heck, Scatman Crothers held up better in “The Shining”). I guess he was there to get in the way of Blake’s attempt on Stephanie’s life (interestingly enough, in 2002 AMC left the nudity in there, which surprised me. That wasn’t a body double for Jill Schoelen, was it? If not, wonder why Brad Pitt went Hungary).

In referencing Freddy Krueger in the write-up, I just realized that in the one screenshot with Susan Blake is wearing a Freddy Krueger-esque sweater. I have no idea if that was intentional or not:-).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Eillio.

Being from the UK, and just a little too young to understand, I didn’t get to experience the whole War on Drugs, “crack pandemic” saga first-hand but have since learned all about it through several outlets. Bill Hicks was my first exposure to it but I read all about it through Noam Chomsky’s works. Also, there’s a (ahem!) CRACKing documentary on Netflix at the moment called Crack that you really should see if you haven’t already. Lots of real-life footage from the 80s.

That’s a brilliant point about the Bundy family, one that didn’t spring to mind while writing. Very perceptive and insightful of you. It would have been a great blooper on Bush’s part. I wish it would have happened for real. 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

Well, for being too young to remember America’s “War on Drugs” (or, as some might call it, the ol’ rope-a-dope) you certainly have a pulse on the attitude of those days and the type of thinking they fostered. When I got older and understood that it was just political posturing (the band Bad Religion would call it “Empty Causes”), I saw more of the complete picture myself.

Once something like crack was introduced, it became a permanently available choice, unfortunately. The plague is certainly real, but a “war” to snuff it out? That’s just not realistic. Like it’s been said, we can never get enough of the things that we don’t need:-(.

LikeLiked by 1 person