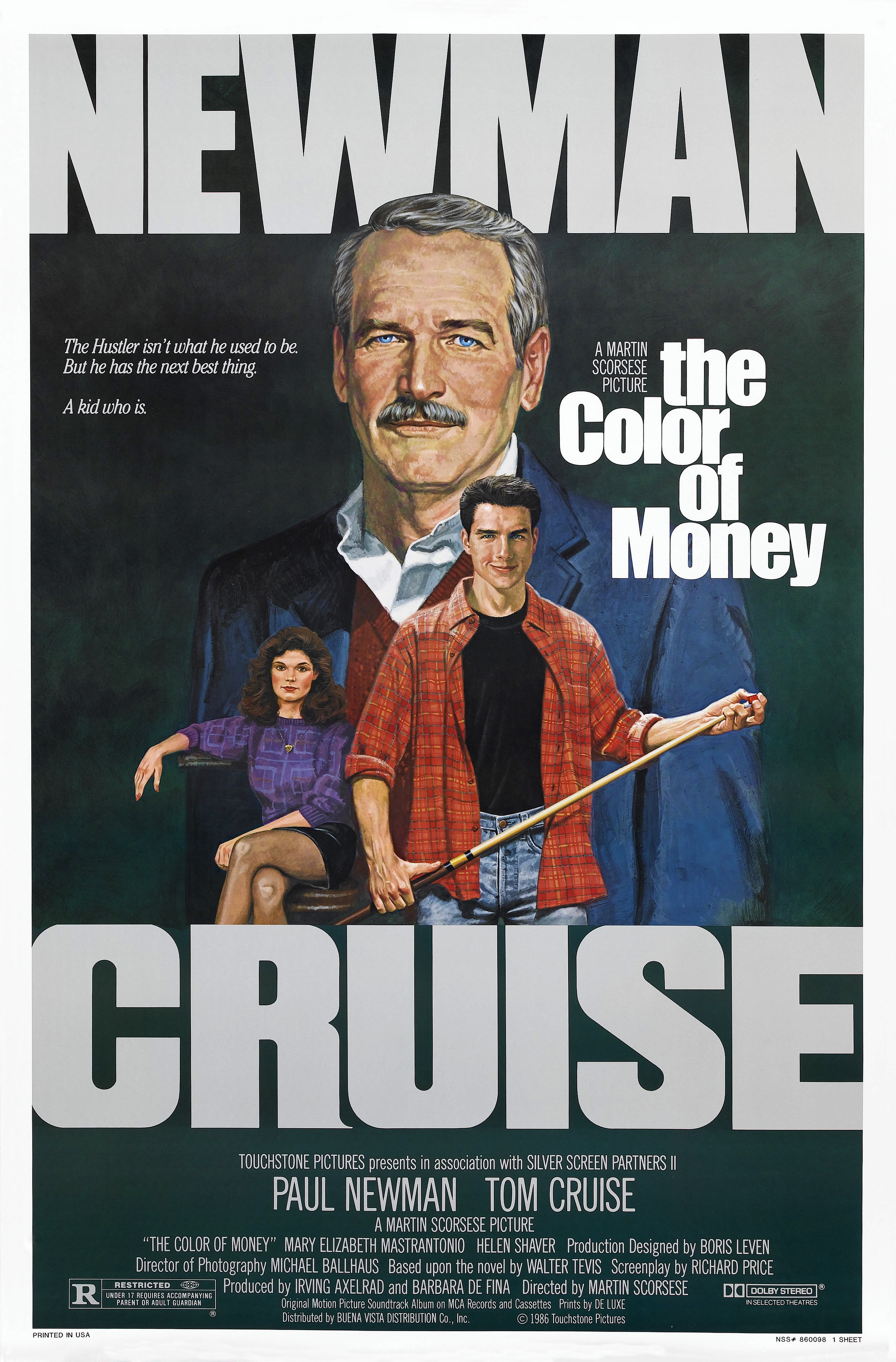

VHS Revival slumps into the smoky pool halls for Scorsese’s punt at studio convention

The Color of Money doesn’t scream Scorsese; his thumbprint is visible, but it doesn’t seem to carry his DNA. Here we have characters that you invest in, that you remember fondly, but the film doesn’t leap to mind whenever the director’s work is discussed. In fact, I sometimes forget it’s even a Scorsese picture.

When I think Scorsese, I think gritty and anthropological (Taxi Driver), slick and dazzling (Goodfellas). I even think quirky and bizarre (After Hours) or the deeply troubling and deliciously offbeat The King of Comedy, movies that may prove divisive among audiences but which ultimately take risks and possess his inimitable personality. Scorsese is as fundamental to cinema as Kurosawa, Spielberg and Kubrick. His movies aren’t just movies, they’re monumental events that are a must-see for anyone who admires the craft of filmmaking. And Scorsese films are, for the most part, unmistakably Scorsese, The Color of Money being one of the few exceptions.

The Color of Money was forced upon Scorsese in the same way as Cape Fear, his 1991 remake of the classic Robert Mitchum-led psychological thriller. Marty, who in his own words has never had much of a business head, almost ostracised himself from the major studios by garnering a reputation as something of an indie filmmaker in spirit. Money was always a secondary factor for him, and despite their critical acclaim, movies such as Taxi Driver were hardly box office friendly, something that made producers deeply unhappy. “There have been serious issues with money over the years,” he would explain. “I have a nice house now, in New York. But there have been major, major issues. In the mid-’80s it was pathetic, I mean, my father would help me out. I couldn’t go out, I couldn’t buy anything. But it’s all my own doing… [The Color of Money] was a calculated business move. I needed the new studio inheads to think they could give me another chance, finance me again.”

The Color of Money also carried something of a creative stigma. For a start, it’s essentially a sequel to 1961’s The Hustler, a movie that first introduced us to one of Paul Newman’s most iconic characters, “Fast Eddie Felson”, a small-time pool hustler looking to strike gold in the precarious world of high-stakes gambling. In an era when the numbered sequel was beginning to catch fire (and a lot of flack in some corners), Scorsese loathed the idea of making a follow-up of any description, the hazards of sequelitis not in-tune with a filmmaker who perused Hollywood’s most phenomenological corners with one foot in the commercial shadows. Scorsese was a student of the game whose favourite directors included industry rebel Michael Powell, similarly ostracised following the release of controversial proto-slasher Peeping Tom, a long-banished film that he played an essential part in reviving, and later Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer‘s John McNaughton, himself blackballed for an audacious docudrama that further blurred the lines in an era of shameless slasher exploitation and moral outrage, but there was something about Newman and the Felson character that really spoke to the filmmaker.

Money won is twice as sweet as money earned.

Eddie Felson

After an incredible 70s run that included Mean Streets, Taxi Driver and Raging Bull, the 80s represented a lean period for Scorsese both creatively and commercially, the mainstream-repellent, yet wonderfully offbeat The King of Comedy and After Hours followed by the deeply troubled The Last Temptation of Christ and underwhelming anthology piece New York Stories. As he had a decade prior with timeless semi-arthouse biopic Raging Bull, the filmmaker would kick off the 90s with genre revolutionising gangster epic Goodfellas, but it was The Color of Money, buoyed by the casting of latest industry heartthrob Tom Cruise and wily veteran Newman, that represented not only Scorsese’s biggest 80s hit, but his biggest to that point, with US box office returns of $52,300,000 (even the hugely controversial, multi award-winning Goodfellas would later fall short with a gross of $47,100,000). Scorsese would often break the $100,000,000 mark post-90s, but in an era of muscles-to-burn action superstars and oversaturated horror hegemony, he failed to reap the financial rewards, despite his reputation as one of the industry’s most talented visionaries.

Newman had first approached Scorsese about the idea of making a sequel in September 1984. The director, who had been in London having just wrapped-up production on After Hours, was intrigued yet dubious about Newman’s unexpected proposal. When he finally received a copy of the script his worst fears were immediately realised. On the one hand, he agreed with Newman’s suggestion that Felson was similar to characters that Marty had previously dealt with, the kind who were remote and unsympathetic, but the original script still felt like a sequel, even featuring clips from the previous movie, which is why screenwriter Richard Price was brought in. Price would keep the source material’s suitably cool, 80s-specific title in an era of Wall Street greed and inner city deprivation, but very little else.

In a 1986 interview with American Film, Price explained how deeply involved he would become with Newman’s baby in an attempt to make the movie feel authentic, hanging around in dingy pool halls and even becoming intimate with some of the regulars, many of whom were aware of the Walter Tevis novel of the same name, which, along with The Hustler, romanticised the lives of men who were little more than glorified bar flies. “If I’m doing a movie about pool hustlers, and if pool hustlers are sitting in the audience opening night, I don’t want anybody getting up in disgust,” he would say. “I don’t want anybody saying, “This is bullshit.” I want people to say, “This is true.” As true as drama and fiction can be true.”

It was such a hands-on approach that would see Price inevitably clashing with Newman throughout production, which may have gone some way to justifying Scorsese’s initial concerns about working with such a high-profile actor from another generation who was used to exerting power and influence on-set and typically getting his way. Newman was understandably precious about a character who had helped shape his career, almost driving co-screenwriter, Price, crazy with his endless script demands. This was a character who the actor felt strongly enough about to revisit after more than two decades, a continuation that he approached with an almost pedantic sense of meticulousness. Such was the preciousness of Felson’s legacy that Newman was worried about what he described as ‘missed opportunities’, an often oppressive approach that led Price to famously retort, “If I hear ”we’re missing an opportunity’ one more time, you’re going to be missing a writer.'”

In Newman’s mind, The Color of Money was his Raging Bull, Felson’s epilogue away from the sport that once defined him. It doesn’t have the artistry or emotional weight of Scorsese’s based-on-true-events biopic, nor the painstaking performance of a young Robert De Niro, who had the weighty dramatic conflict of the real-life Jake LaMotta to tap into, but Newman is a born movie star who can do so much with so little, his second turn as ‘Fast’ Eddie more than deserving of the Best Actor Oscar that he would ultimately land. Whether that Oscar was more of a token gesture after previous losses is open to debate, though Bob Hoskins was just as deserving for his role as a smitten working class gangster in Neil Jordan’s superb and sobering neo-noir crime drama Mona Lisa, a British independent movie about prostitution and unrequited love that proved much grittier than its dazzling Hollywood counterpart.

That’s not to say that The Color of Money isn’t gritty in its own right. There are obvious comparisons to be made between LaMotta and Newman’s effortlessly cool, gracelessly ageing pool shark. Both are former champions and both attempt to stay relevant beyond their glory years, the former as a bloated night spot raconteur, the latter as a booze-addled coach drifting towards the wrong side of clarity. Newman is a colossal presence as the older, wiser and just a little bitter pool hall ghost, his diamond glare and ruggedly suave aura commanding every last frame. It’s clear that he cares deeply about one of his most emblematic characters, hanging on his every emotion like a gambler chasing the pitiful scraps of dwindling good fortune. Whether he’s stewing in whiskey, exploding into flashes of manipulative rage or simply hanging back as his precocious student pings off the walls with puerile bravado, his aura permeates this movie. Much like Scorsese, the man in the shadows is forever front and centre.

You gotta have two things to win. You gotta have brains and you gotta have balls. Now, you got too much of one and not enough of the other.

Eddie Felson

Felson’s protégé is played by an up-and-coming Cruise, who possessed all the Hollywood sizzle that Marty required for a gig that was designed to please the industry’s money men. Cruise oozes star appeal as the petulant Lauria, treading a fine line between boyish charm and nauseating arrogance as he sets about learning from and ultimately outdoing his mentor. Felson is no longer a pool player. He’s a hustler of an entirely different variety, corrupting a wet-behind-the-ears Lauria for his own financial gain, but also as a means to vicariously return to the sport he has long-since walked away from in a competitive sense. To an extent Lauria is an extension of Felson’s ego, a residue of some barely glimpsed redemption. Scorsese has often relied on youthful exuberance when it comes to movies with delinquent themes, actors such as Ray Liotta and Leonardo DiCaprio adding a roguish, blue-eyed charm to Henry Hill and the battle-hardened Amsterdam, respectively, and Cruise, still a rookie in his early twenties, is nothing short of a revelation.

Caught between the movie’s two male stars is Vincent’s hard-faced love interest, Carmen (Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio), who had burst onto the scene three years prior as Tony Montana’s naïve and ill-fated sister Gina, a quasi-incestuous role of precocious complexity. Under Brian De Palma’s tutelage, the silver screen rookie more than held her own starring alongside Al Pacino in one of his most iconic roles, and again she refuses to be overshadowed as the flirtatious and cunning Carmen, a loose beauty who seems both loyal and ready to jump on the next runaway train that happens to rattle through her stripped-down vicinity. Whenever I see Mastrantonio I’m awestruck. It amazes me that she doesn’t get more plaudits because for me she’s one of the finest actors of her generation. It was only Marlee Matlin’s astonishing performance in Children of a Lesser God — unique for being the only Academy Award winning turn by a deaf performer — that prevented her from bagging an Oscar of her own.

When we first catch up with ‘Fast’ Eddie he’s long-since cooled his motor. He peddles whiskey; mainly, you suspect, so he has a constant supply at hand. One typically boozy evening he spies the relentlessly brash Vincent, who loves nothing more than showing off his prodigious pool hall skills in a manner that sees any potential pigeon flutter away before the chalk has even left the cue. Eddie sees a bit of his old self in Vincent, and immediately the haze clears and those hawkish instincts begin to sharpen. He knows he can make a winner out of the kid and is determined to snare and mould the kind of talent that doesn’t come along too often.

That talent wasn’t entirely a work of fiction, either. In fact, Scorsese would claim that both Newman and Cruise became rather handy with their cues during shooting, which meant some of the film’s dazzling trick shots were quickly in the bag, making a potentially difficult production relatively simple. This would only add to a movie that is stylised in a way that aims for and achieves an often startling aura of off-the-cuff authenticity. “Sometimes I’d think it was going to take 17 or 18 takes to get a ball to go into a certain hole,” the director would recall, “but then we’d nail it in two takes!” It might not seem like a big deal with all the technical talent at hand, but believing in who you are and what you’re doing can be vital to the energy and camaraderie that bring such movies so indelibly to life. When it comes to delivering the sporting goods, The Color of Money is as slick as they come.

Even more vital to the smoothness of proceedings was late cinematographer Michael Ballhaus. Ballhaus, who was set to work with Scorsese on The Last Temptation of Christ until a ballooning budget and widespread protests from religious groups put the project on hiatus, would collaborate with Marty on such future classics as Goodfellas, Gangs of New York and The Departed, but it was 1985‘s After Hours that the two first worked on together. The Color of Money was their second collaboration, and Scorsese would speak in glowing terms about the influence that Ballhaus had on his work at a time when filmmaking had suddenly become a daunting prospect. “Working with Michael was a sort of rebirth for me,” he would tell American Cinematographer. “On After Hours, we had the chance to see if we could make a film with the energy level I had when I did Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore or Taxi Driver. The great thing about Michael on that film was that he was so enthusiastic about my shot designs. He was very, very helpful in getting exactly what I wanted. We had a lot of fun figuring out what type of lens to use, how fast or slow to move the camera and in what direction. It was like rediscovering how to make movies — together. He really gave me back my faith in myself about how to make films.”

It is during those pool hall scenes that The Color of Money more closely resembles a Scorsese movie. The action is flamboyant, edgy and dynamic, beautifully capturing the precarious allure of the game and everything that it stands for. Its players may be lowdown hustlers stuck to the boot heels of society, but under the lights they become overnight celebrities, enthused by the spotlight and sinking into the muggy ambience of their muted back alley stage. “I lit the movie the way these pool halls were lit,” Ballhaus would explain. “I illuminated the tables’ felt surfaces, letting the areas beyond the tables fall off into darkness.”

You win one more game, you’re gonna be humping your fist for a long time. Got that, Vincent?

Carmen

That darkness plays host to a colourful array of notable cameos from a plethora of future stars. A young John Turturro plays a cocaine-friendly table crawler who is quickly duped by the fresh-faced Vincent, an equally youthful Forest Whitaker delivering an astonishingly assured performance as a gentle giant whose au naturale hustle seems to get the better of Felson’s blunted instincts. It’s here where Felson rediscovers his old self, resulting in the kind of climactic battle that reunites our warring rebels on the most fundamental level. The way Whitaker, only 24 at the time, holds his own against one of the industry’s biggest stars is nothing short of phenomenal. The sheer wealth of burgeoning talent on display is palpable.

The film’s climatic scenes feel like a decisive moment in the relationship of a son and his estranged father. Until then, Eddie and Vincent’s relationship is a tenuous and complex one, especially as Eddie sees so much of the kid in himself. Vincent is suckered-in by his mentor’s painstaking ambitions, seeing the old shark as something of a paternal figure as he attempts to keep his protege’s ego at bay in favour of the long con. The old man seems to be playing a calculated game as he continually gives the kid enough rope to hang himself with before tugging at his leash, pulling him away from temptation with one hand and pushing him towards failure with the other.

Inevitably, this game of give-and-take leads to an abrupt separation and a final showdown at a pool tournament for the region’s finest. Ultimately, Eddie creates something of a monster in Vincent, turning a naïve pawn into a ruthless punk who is devoid of ethics, the kind who will inevitably flourish in an environment where everybody is looking for the next sucker to leech off. The tournament is also a chance at redemption for Eddie. Through Lauria he is able to rediscover his passion for playing the game, the highs and lows that make it such an irresistible draw.

Can The Color of Money be deemed classic Scorsese? In terms of possessing many of his inimitable hallmarks, perhaps not, but the movie oozes cult appeal, Newman’s old-dog-rediscovering-old-tricks act hard not to get behind as we slump into the dank of pool hall skulduggery. The film may be a concerted commercial effort on the part of an innovator forced into appeasing Hollywood’s money men, but it doesn’t jeopardise its integrity in any serious way. In fact, the movie still has something of an indie vibe, concerning itself with characters who err on the side of low-key dysfunction. Ultimately, it falls short of Scorsese’s finest, but that shouldn’t be the extent of our relationship with the movie. The director takes his foot off the peddle and allows others to take charge of characters who are not his own, characters who others convinced him to get involved with at a precarious time in his career. Perhaps for those reasons, The Color of Money is not the kind of spectacle we have come to expect from an innovative player such as Marty, but for once the show isn’t about him. It’s about one of cinema’s most iconic characters and the equally iconic star who portrays him. For both, it’s a fitting swansong.

Director: Martin Scorsese

Screenplay: Richard Price

Music: Robbie Robertson

Cinematography: Michael Ballhaus

Editing: Thelma Schoonmaker

You’ve given me a new way to look at “The Color of Money” (I still see the color as green and in my wallet though): I always thought it was good (speaking of songs accompanying films, I also dig Eric Clapton’s “It’s in the Way That You Use It”, and recorded the tune off VH1 back in 1991), but I guess I was one of those people who didn’t feel this film was a very Scorsese film, but the explanation of that in this essay answers any questions of why that is, so I’m pretty satisfied. I never saw Scorsese as an indie director, but upon reflection, yeah, I guess he is:-).

I always thought Paul Newman should’ve won for 1982’s “The Verdict”, but I’m glad he received an Oscar here.

I agree on Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio’s character in the film, as she bought an attitude (and agenda, as stated in the essay) to the story. I’ve always liked Helen Shaver as well (those Canadian actresses, like her & Margot Kidder, have always brought something to the table for me), even though I don’t believe she had a ton to do here.

LikeLike

I’m delighted I’ve given you a new way to look at The Color of Money; coming from you that’s a real compliment (this is Eillio, right?).

Scorsese was certainly high-profile based on his skill and innovations but he can be considered an indie director in the sense that he never really considered maximising profits and had all but ostracised himself from major studios by the early 1980s because, despite his profile, he failed to secure blockbuster returns.

The Color of Money was a response to this and it shows. It’s also technically a sequel with characters that are not the director’s own: all reasons why this doesn’t really feel like a Scorsese movie. Ballhaus worked his magic here though. He and Marty were a match made in heaven.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Edison, yes, this is Eillio:-). I haven’t been able to comment in a few months since I was using a library computer; I couldn’t visit VHS Revival directly due to The Buffalo & Erie County Public Library having that sight listed as porn (can you believe that!!! I mean, Marilyn Chambers did “Rabid”, but c’mon here). Fortunately I’m currently in Jacksonville, FLA and their public library doesn’t seem to mind, although my wallet takes a hit since it costs 2$ to use their computers (I currently have no legal residence in Jax, or an illegal one really:-). i was able to still read the articles via e-mail, so I wasn’t completely shut out, just silenced (my phone has internet but is rather limited).

But yeah, I was a little withholding on my regard and virtues for the film, never went all the way with it, because of feeling like Scorsese didn’t leave what I consider his usual fingerprints on the film. It really holds up for me though, and I liked everything about it, but the Scorsese part just never clicked with me. I agree though, recent Scorsese flicks weren’t blockbusters (I don’t care what anybody says though, I like “New York, New York” and “The King of Comedy”, but they definitely weren’t seat fillers or box office gold).

LikeLike