Brian De Palma’s phenomenal horror adaptation remains one of the genre’s true giants

Whenever queried on my favourite horror characters, the usual suspects leap out with the unyielding complacency of a swift, no-nonsense killer. They’re generally the big franchise monsters – Leatherface, Fred Krueger, Michael Myers – brutal, vindictive slayers who spell out their wicked intentions in no uncertain terms, but despite her relative and rather appropriate inability to fit the mould, Sissy Spacek’s Carrie may be the best of the lot.

The same can be said of the movie itself. Brian De Palma’s first mainstream hit is incredibly assured; simple, focused, and immaculately crafted – one of a handful of horror movies released throughout the years that might be considered perfect. That simplicity, at least by today’s standards, was such a refreshing experience when revisiting this past week. A concise, 90-minute movie that never outstays its welcome is quite the rarity well into the 21st century, especially the kind that gives you everything you could ask for and then some.

Carrie doesn’t have the press-baiting baggage of De Palma’s early-80s output, movies like Dressed to Kill, Scarface and Body Double becoming the ire of violence and feminist groups who criticized his insensitivity towards sexual minorities and a propensity for weakly sketched female characters who typically met nasty, perverse ends, but at a time when horror was maturing, veering away from the supernatural villains of yore for themes that were much more relatable and closer to home, landing in a post-Watergate environment of cynicism and distrust, it certainly treads touchy thematic territory, possessing the kind of startling images that must have had the real Margaret Whites of the world reaching for crucifixes across America.

There is nothing weak about Carrie White, even if her disconcertingly wicked classmates seem to think so. She ‘eats shit’ everyday at high school, retreating into her shell as an even worse fate awaits her at home, but she is strong and determined in the face of her fundamentalist mother when a glimmer of hope contrives its way into her suffocatingly introverted life, an unlikely and mostly genuine homecoming date that ends in disaster, confirming, however tenuously, the oppressive ravings of her paternal master, who represents the very worst of what religion has to offer. In fact, Carrie is full of strong female characters, particularly Betty Buckley’s determined, goodhearted gym teacher, one of many victims to succumb to Carrie’s partially misdirected fury. In fact, besides William Katt’s blonde lothario, Tommy Ross, and an ignorant headteacher who refuses to get Carrie’s name right, there’s barely a male character worth remembering in the entire movie. Even a pre-superstardom John Travolta, despite his megawatt natural charisma, is something of an outsider looking in.

It doesn’t hurt that Carrie was also the breakout novel of one of horror’s most prolific, best-loved writers. Stephen King was a 26-year-old teacher-come-laundry worker when Carrie’s paperback rights were sold for a mammoth $400,000, ushering in a literary horror boom that, much like the cinema of the same period, broke with past traditions to reflect, among other things, political and sociological themes such as the Vietnam War and the serial killer explosion, all of which was suddenly beamed into homes across the world thanks to the evolution of technology and the modern media. This was more than a decade after European horror had usurped America’s once ubiquitous ‘red scare’ era, movies such as Roman Polanski’s Repulsion exploring the emotional breakdown of female characters who replaced monsters and mad scientists as the genre’s conceptual focal point, something that De Palma channels in his phenomenal adaptation.

It has nothing to do with Satan, Mama. It’s me.

Carrie White

Fittingly, if it wasn’t for King’s wife Tabitha, Carrie, and the mammoth career that it would spawn, may not have existed. Based on his brief time spent working as a school janitor, an article in LIFE magazine about telekinetic phenomena as an explanation for supposed supernatural incidents – the kind that would shape the horror genre thanks to hits such as Rosemary’s Baby (1968), The Exorcist (1973), and The Omen (1976) – and two deceased girls from King’s own high school who would ultimately form the Carrie White character, the author’s original draft quickly found its way in the trash due to his insecurity in regards to writing not just a female character, but a teenage girl, and only resurfaced after his partner fished it out with the promise that she would assist him.

As King would explain, “Two unrelated ideas, adolescent cruelty and telekinesis, came together, and I had an idea. The story remained on the back burner for a while, and I had started my teaching career before I sat down one night to give it a shot. I did three single-spaced pages of a first draft, then crumpled them up in disgust and threw them away.

“The next night, when I came home from school, Tabby had the pages. She’d spied them while emptying my waste-basket, had shaken the cigarette ashes off the crumpled balls of paper, smoothed them out, and sat down to read them. She wanted me to go on with it, she said. She wanted to know the rest of the story. I told her I didn’t know jack-shit about high school girls. She said she’d help me with that part. She was smiling in that severely cute way of hers. ‘You’ve got something here,’ she said. ‘I really think you do.'”

Carrie may not be one of De Palma’s most controversial movies, but the literary equivalent remains one of the most frequently banned books in American schools thanks to its heady cocktail of violence, cursing, underage sex, and, most notably, its negative views on religion. Historically speaking, religion and high school are two of America’s proudest, most sacred institutions, the two culturally intertwined, and though the former continues to lose influence in public life in the 21st century, it remains the world’s key motivation, or excuse, for war and conflict, and continues to be a deeply sensitive subject for many.

Perhaps one of the reasons why, against all of my best instincts, Carrie doesn’t immediately leap to mind when those questions regarding the best of horror arise is the fact that the movie works less as a straight-up horror, more as a psychological drama with horror embellishments, which, though lacking the overtly horrific nature of something like a slasher, makes it that more affecting. If you’re exceedingly unlucky, a Michael Myers might show up on your doorstep one fateful night, but there’s a Margaret White in every neighbourhood.

As much of King’s work over the years will attest, there is also a bully with borderline homicidal tendencies in every school. Much like William Golding’s debut novel ‘The Lord of the Flies’, Carrie exposes children as humanity in its rawest form; a callous, venomous breed without conscience who will happily bully and torture as a source of amusement, or, in the case of Nancy Allen’s queen bitch Chris Hargensen, with an unyielding compulsion to destroy and humiliate, whatever the consequences.

The movie’s infamous opening scene, a dreamy, almost idyllic snap of high school life that suddenly descends into a hellish nightmare of harrowing distress, outlines the film’s intentions absolutely, taking a rusty dagger to the heart of the American dream. This is not a portrait of naive adolescence, of kids stealing their first kiss behind the bleachers, of young hopefuls forging life-long friendships, it’s a claustrophobic grotesquerie, a carnival of teasing and taunts that land with the brutish blows of a death-delivering blunt object. It attacks the insecurities of adolescence with an all-too-real savagery. This is a breeding ground for America’s capitalist beast, a place where the weak are weeded out and flattened with a devilish smile and a flip shrug of the shoulders. For the leering girls of the Hitchcockian Bates High School, Carrie’s unending pain and humiliation barely registers.

For Carrie, home life is no less stressful, and, ultimately, far more dangerous. Her mother is a relentless maelstrom of self-loathing, all of it projected onto a child who is so shielded from the real world that when her first period strikes that fateful day, triggering the supernatural powers that will lead to a generational tragedy for the town of Chamberlain, Maine, she reacts as if death itself has come to pay her a visit. Dining by a particularly ominous and imposing image of The Last Supper and forced to repent in a closet-come-makeshift confessional presided over by a demonic, cat-like image of the crucifixion, Carrie lives an almost medieval existence in a crumbling suburban prison that rests like a home for the criminally insane in an otherwise run of the mill American suburb.

All of this stems from the disappearance of an absent father, either driven into the arms of another woman by his wife’s growing fanaticism, or indeed acting as the trigger for it. She projects her own fears onto her child, presumably terrified that one day she will lose her too. As an atheist, I can still appreciate the reassuring qualities of religion for the lost and lonely, but the fear, self-denial and outright hypocrisy of religious fanaticism is arguably the world’s most potent evil.

Piper Laurie is phenomenal as the fanaticist in question, plaguing not only Carrie, but everyone she comes into contact with. An early scene in which she visits the home of Carrie sympathiser Sue Snell’s mother gives us a glimpse at the incessant, holier-than-thou attitude that drives her, an unrealistic devotion designed to ward off the ever-impending wrath of god, who in his benevolence apparently has very little patience for even the smallest imperfection. Mrs. Snell has no intention of being preached at in her own home and so offers a generous donation as a deflection. Mrs. White snatches the offering, but the sense of disgust and superiority is palpable. She just can’t help herself.

Scenes featuring Carrie and her mother are much more unsettling, unrepentant away from the eyes of the world. Physical abuse and godlike displays of self-righteousness reduce a quivering Carrie to the rank of maltreated animal as her mother marches around like some kind of holy militant, recklessly wielding a butcher’s knife, thrashing wildly about the place or brooding from the abode’s most ominous corners. Later, after Carrie’s prom night defiance, Mrs. White emerges from a devilishly catatonic state, wielding her weapon of choice in an almost ecstatic state of exultation as she attempts to cleanse her offspring forever. When she finally succumbs to her daughter’s telekinetic protestations, impaled with a barrage of blades in a moment of desperate self-preservation, she is a mirror image of the iconography that has plagued Carrie’s childhood, her lust to live and die in god’s image gruesomely and ironically realized. It remains one of horror’s most haunting scenes.

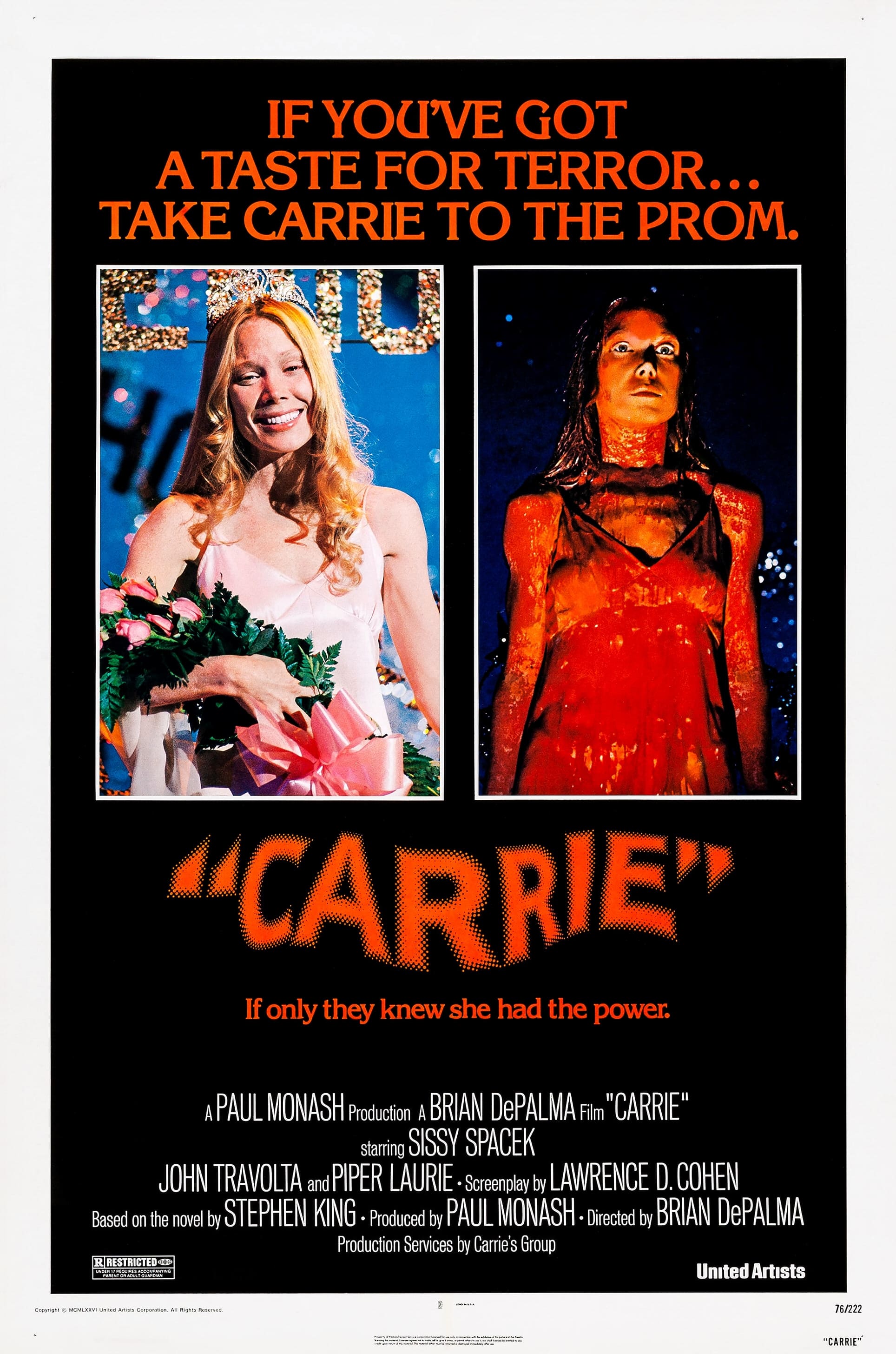

More great casting comes in the form of Carrie herself. Sissy Spacek left behind a career in TV and commercials with her breakout role, which would earn her the first of six Oscar nominations, and she becomes Carrie White body, mind and soul, creating a character who is worthy of our sympathy without ever falling into pitiful territory, ducking confrontation as she tries, unsuccessfully, to remain invisible. She isn’t your typical blonde bombshell. She doesn’t have the cute as a button, Disney qualities of a Jessica Harper, but she’s perfect for the role. She’s unique and talented enough to pull off the put-upon outsider without the aid of heavy eyeliner or the abundance of cheap visual aids that would become commonplace for such characters, and when she relents and turns up to the prom as Tommy’s date for the evening, she is genuinely knock-out beautiful. She’s so much more than the mountains of one-dimensional scream queens who would follow.

Early De Palma go-too girl, Nancy Allen, is also hugely impressive as Carrie’s one-sided nemesis, Chris. Sure, the role is much more one-dimensional, perhaps the easiest kind to pull off in the genre, but you fucking hate this bitch from second one. She is the complete antithesis of her persecuted classmate: bold, traditionally beautiful, and popular, becoming the undisputed queen bee, and, like most bullies, ruling through fear. She abuses Travolta’s dull-witted bad boy Billy Nolan, continuously putting him down with that nasty glint, despite his warnings. She even smacks him around when she doesn’t get exactly what she wants, which must have been quite the shock back in 1976. Her acts of flippant cruelty and incessant self-regard go beyond mere adolescent brattiness. Her behaviour, and the lengths to which she goes to destroy and humiliate a harmless innocent, verges on the sociopathic.

I should’ve killed myself when he put it in me.

Margaret White

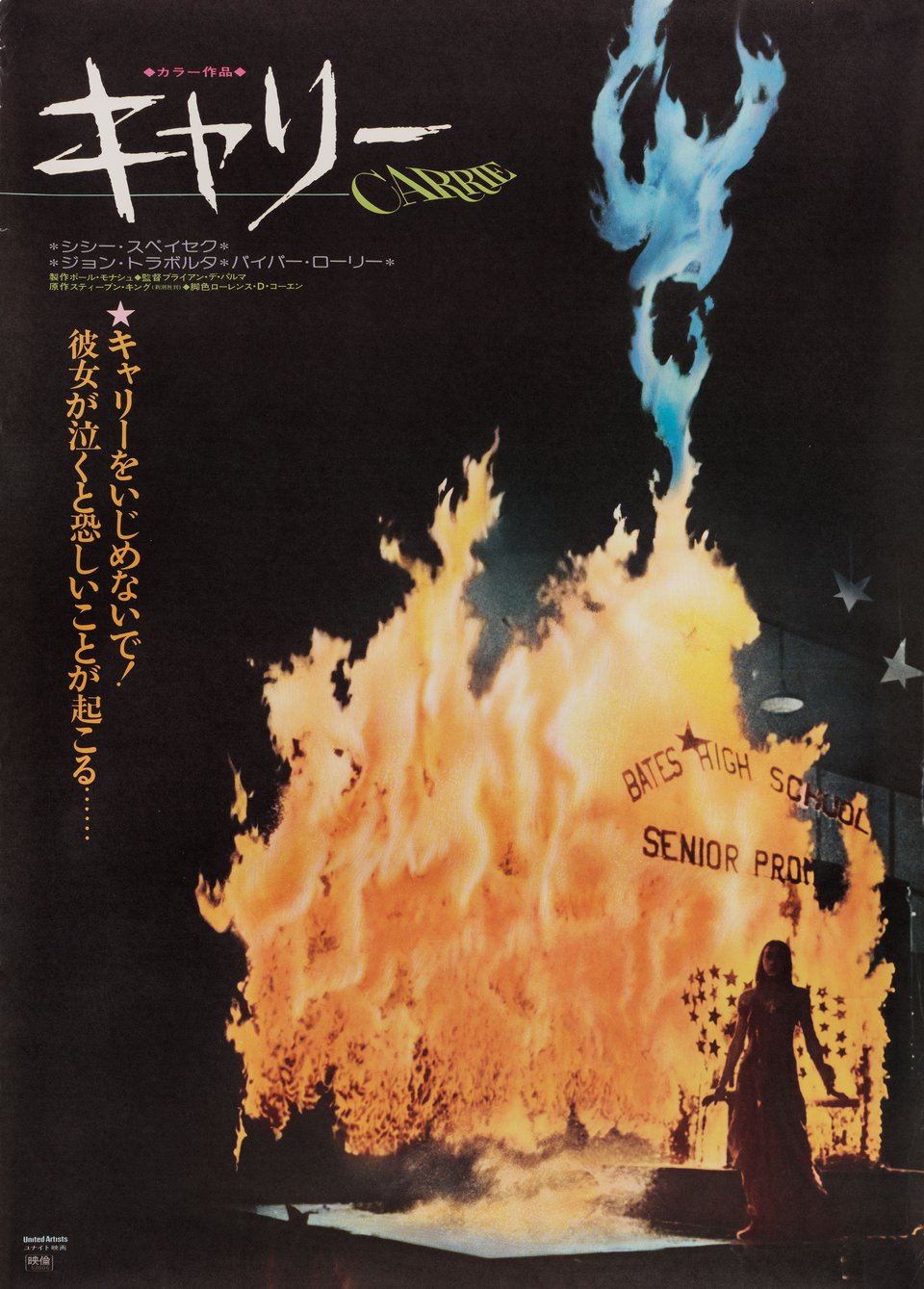

Despite an abundance of moments that might be considered equal or even superior, Carrie is all about the hellacious prom night pay-off, and what a masterclass it is. Some scenes scream into the cultural zeitgeist, their power and influence refusing to let go. They become scorched on the brain, their legacy transcending generations, and this one is up there with the very best of them. The detail with which De Palma sets his protagonist up for arguably cinema’s cruelest fall is absolutely gut-wrenching, going some way to justifying an act of revenge that becomes unfortunately misguided among the mayhem and humiliation.

Pranks are cruel by their very nature, and with so much at stake for our protagonist, it cuts even deeper, not least because this is no ordinary prank. Drenching someone in pig’s blood (PIG’S BLOOD!!!) is about as vile an act as I can strain to imagine that doesn’t involve an automatic prison sentence. The mess, the stench, the connotations with sacrifice, the absolute cruelty of intention and the trauma that it embellishes. This is Stephen King at his wicked, twisted best.

What makes the scene so excruciating is the brief fairytale that precedes it. Carrie is understandably suspicious of Tommy’s intentions, but her domestic defiance initially seems to be the right choice. Carrie blossoms in those scenes. She’s courageous, beautiful, almost dizzy as she dances in the dreamy filter of De Palma’s cinematic chicanery. Many of those watching are genuinely happy for the school’s perennial outcast as she accepts her unlikely role as prom queen. De Palma piles on the Cinderella idealism as the unthinkable edges ever closer, crawling inevitably upon us in slow, agonizing detail, and when the deed is finally done, dawning upon the shocked and appalled faces of the majority of those watching, you’re still not prepared for it, and if you’re like me you never will be.

The fury that Carrie unleashes is unrepentant, and, a few unfortunate casualties notwithstanding, irresistibly satisfying. Lost in a world of pain and uncertainty, she unleashes the full fury of her pent-up gift in the most ferocious fashion, hellbent on the destruction of everyone present. The release as she stalks the dancehall, omnipotently taking out anyone who has hurt or embarrassed her, is palpable, a devilish act of revenge that sees her finally living up to her mother’s irrational fears. She even takes out those who are fighting her corner, Miss Desjardin ruthlessly dispatched with as Carrie wrongly imagines the taunts and ridicule of everyone present, a detail that is crucial for preserving the character’s heroine status. The spilt screen chaos is still deeply unsettling almost half a century on.

If all of that wasn’t enough, Carrie also features one of cinema’s great jump scares. It may have become diluted in an industry that is awash with them, entire movies depending on that shock factor to the point of numbness, but the sight of a deceased Carrie’s hand appearing from a makeshift grave to grab at the tortured imagination of advocate Sue is a sublimely executed final scare, a fitting end for a classic horror tale that relates on a deeply human level.

For all the flesh-dripping, supernatural monstrosities cooked up in the Hollywood laboratory, the world’s real horrors arrive quite naturally, emerging from the seemingly innocuous and mundane. Mental illness, religious zealotry, even the unconscionable modus of unabashed adolescence make the likes of Fred Krueger seem quaint by comparison. De Palma has often been compared to Hitchcock in unflattering terms, the director accused of aping his style to an overbearing degree. He’s certainly influenced by the ‘master of suspense’, something he has been very open about, but Carrie has stood the test of time along with the likes of Psycho. It is a bona fide horror classic of the highest order.

Director: Brian De Palma

Screenplay: Lawrence D. Cohen

Cinematography: Mario Tosi

Music: Pino Donaggio

Editing: Paul Hirsch