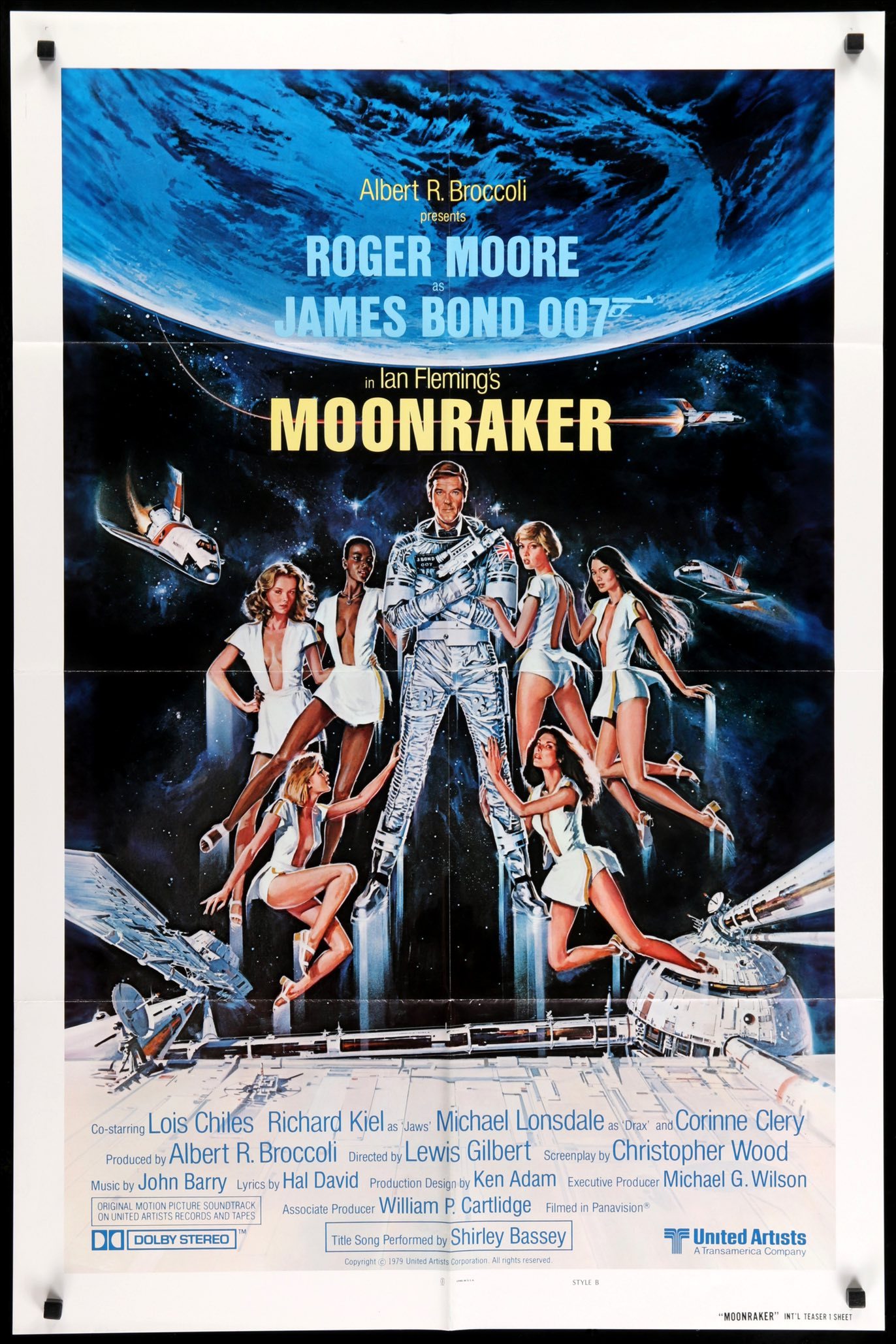

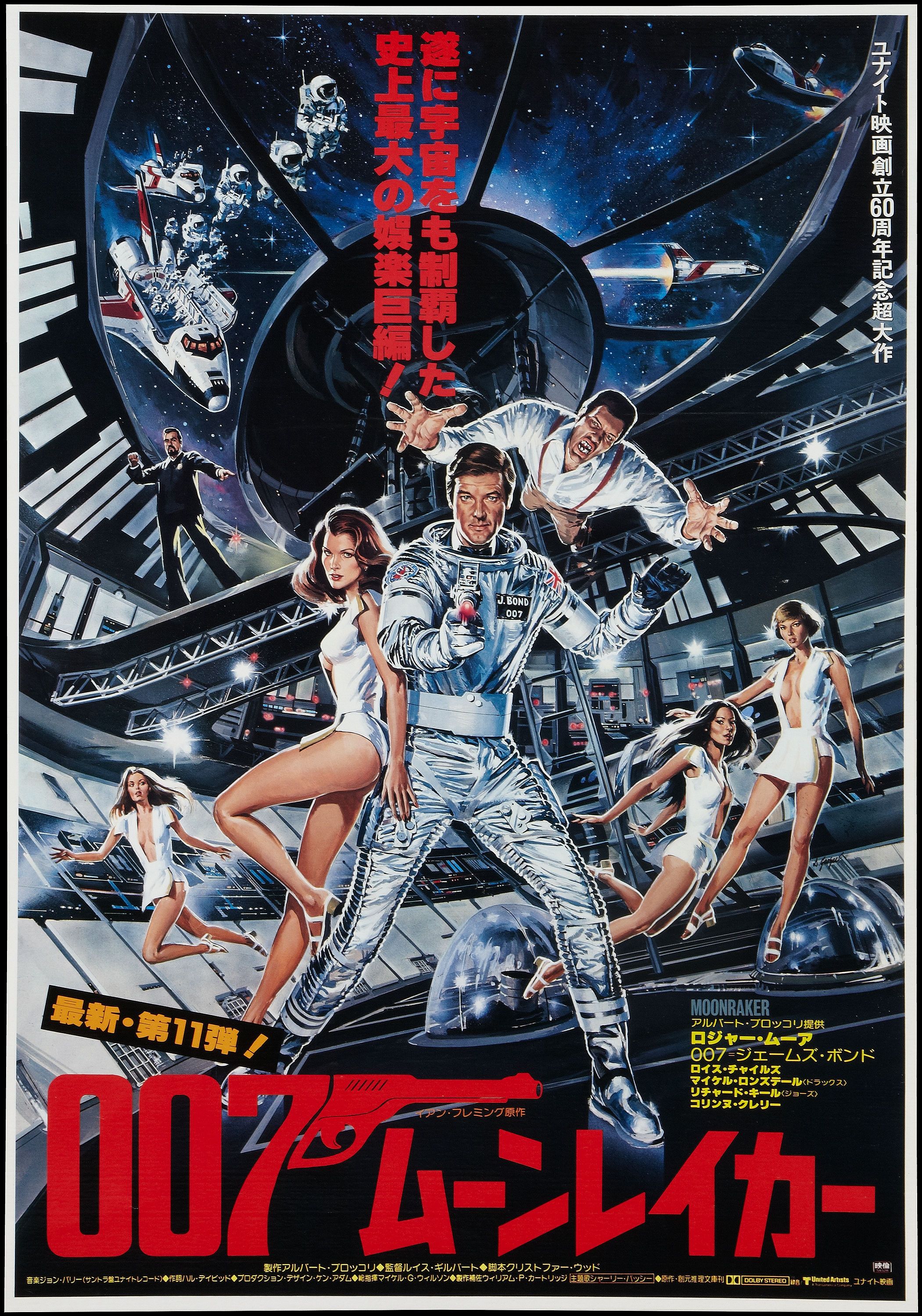

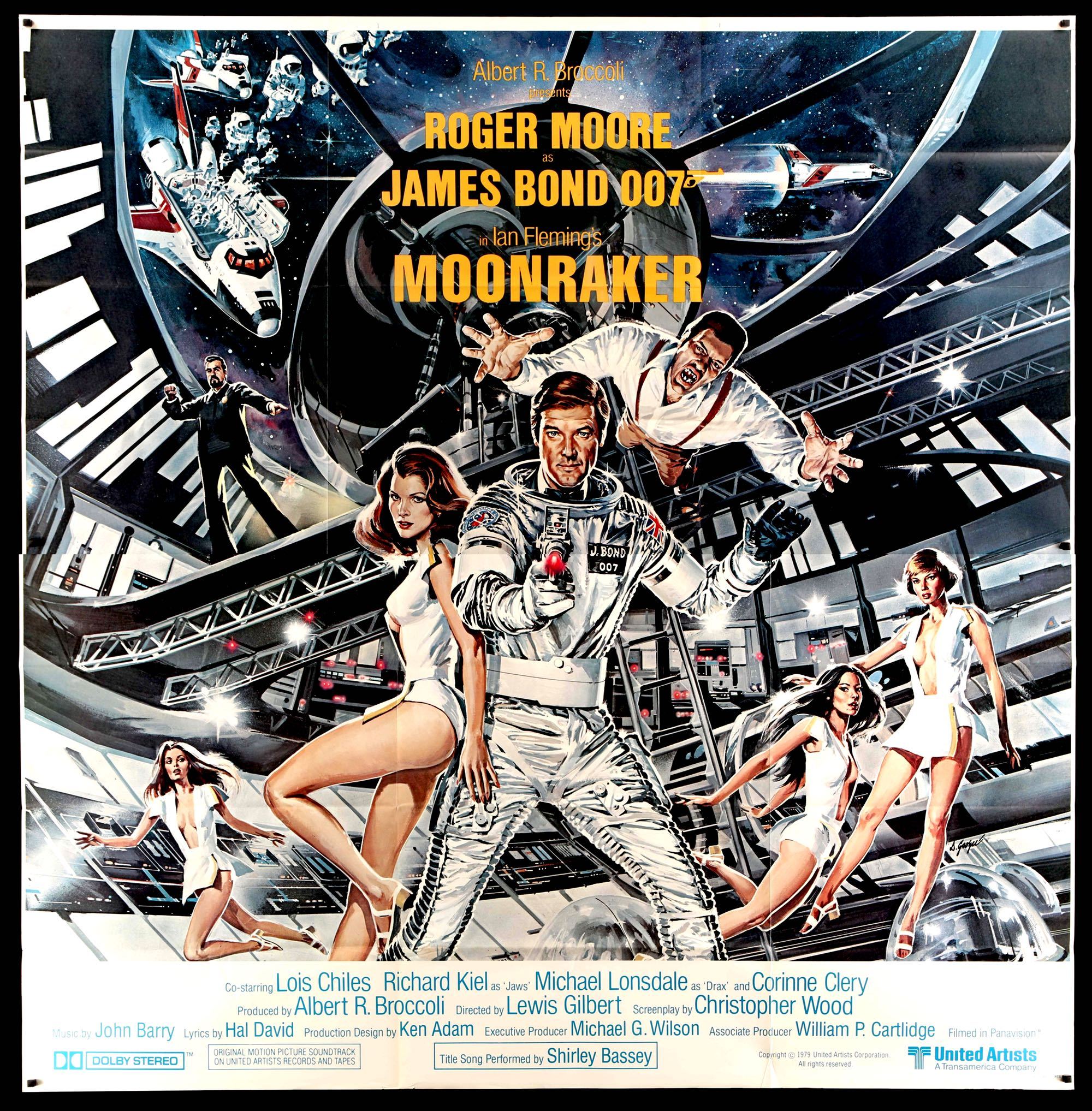

Roger Moore boldly goes where no Bond has been before

Those who are familiar with VHS Revival’s James Bond coverage will know that I am something of a Moore apologist. I say this because many fans cry foul over Roger’s eyebrow-raising antics and his decision to play Bond as a lover rather than a ruthless, Fleming-esque spy. I think part of this can be attributed to the changing times. Bond has been a part of the zeitgeist for so long, the character constantly evolving to suit cultural and political trends. Moore came after the civil rights movement, his cosmopolitan, comparatively carefree lover man very much a product of the 70s, which, along with his advancing years, is probably why many viewed his later efforts as irrelevant. Moore’s successor, Timothy Dalton, was far more attuned to the relatively grounded, Cold War 80s, but much to the chagrin of many, Roger would stick around for just a little while longer.

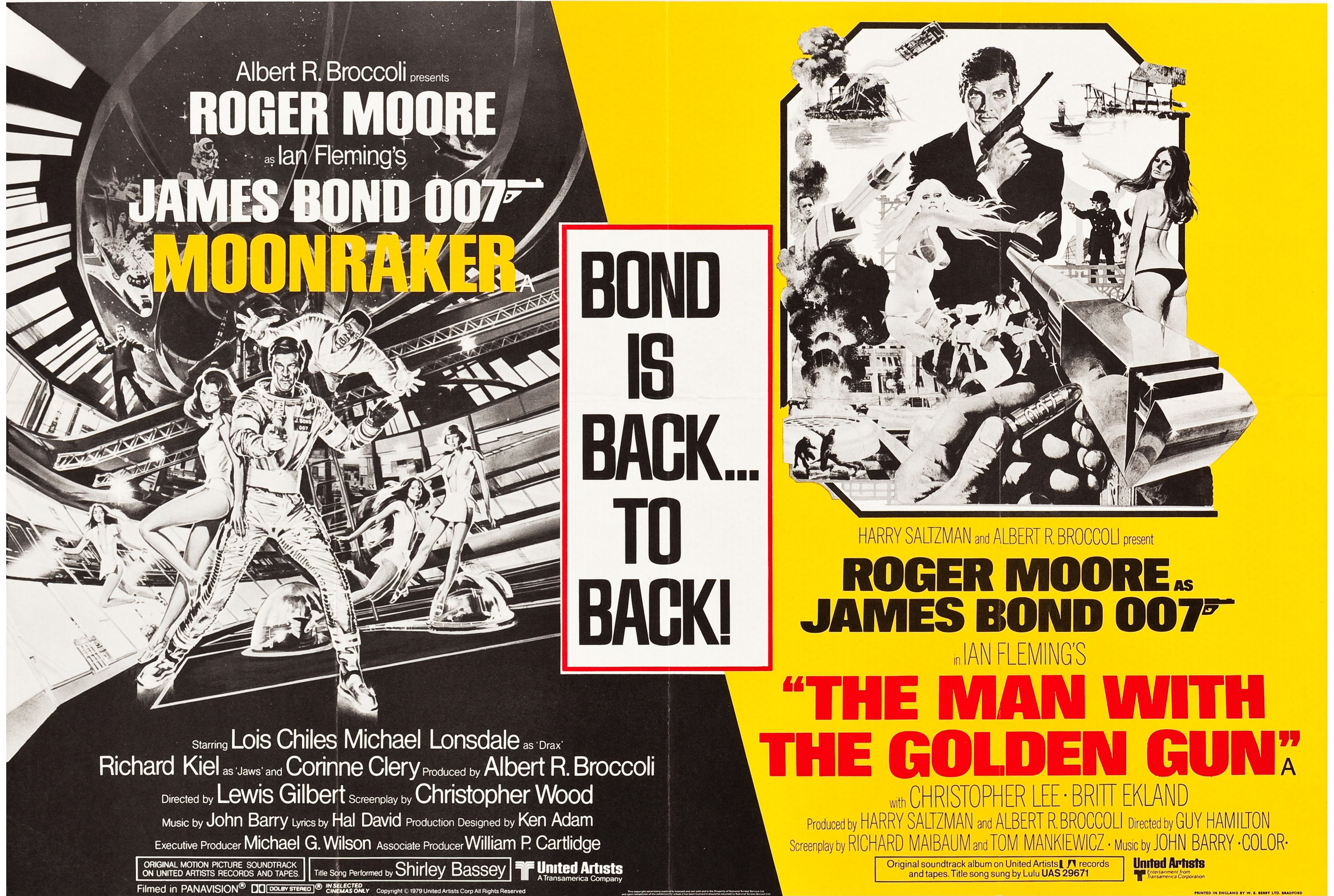

Initially, Moore wasn’t supposed to make it past 1977‘s The Spy Who Loved Me until Moonraker was rushed into production in order to cash-in on the popularity of Star Wars, a franchise that would temporarily usurp Bond as cinema’s most beguiling attraction. Many had grown tired of Roger’s salacious antics, but a fourth appearance as the irrepressible 007 was a financial cherry that was just begging to be picked, and it would turn into a rather juicy one, Moonraker becoming the highest grossing film worldwide in 1979 with a whopping $210,300,000 in box office returns. When director John Glen took the reins in 1981, he once again tempted Moore back into the fray, worried that his debut would falter without the veteran actor’s steady hand. Moore would star in a further two instalments in 1983’s Octopussy and 1985’s A View to a Kill, the latter featuring a 58-year-old actor who was way past his sell-by-date, many getting their wish by finally seeing him put out to pasture.

Without Moonraker, Moore may very well have called it quits, but fate has a habit of interceding when you least expect it. From a production standpoint, Moonraker was like the red-headed stepchild of the Bond series. In fact, it’s a miracle that it even got made, and it wasn’t for the lack of trying. Fleming had intended Moonraker as a feature film even before the completion of his novel in 1955, part of which was written with a screenplay in mind as he looked to broaden Bond’s commercial horizons. The rights were initially optioned by actor John Payne and later sold to Pinewood Studios subsidiary Rank Organisation, who just weren’t interested in making it, even after Fleming provided them with a script with a view to pushing the proposed project into development. If it wasn’t for the success of Star Wars and wholesale changes to the original story, the film may never have come to fruition. During the end credits of The Spy Who Loved Me, For Your Eyes Only, released two years after Moonraker, was even advertised as the next instalment in the series.

Thanks to Eon’s derivative aspirations, Moonraker did make it to the silver screen, and did so with a spectacular wallop. The movie was quickly and crudely sandwiched in to coincide with the Star Wars sci-fi boom, which had briefly threatened to make the Bond series passé, but 007 is nothing if not adaptable, and if anyone could pull off such an extreme shift in tone it was the wholly self-aware Moore. Moonraker wasn’t the first or last Bond movie to wildly deviate from its source material, but asides from featuring the same villain, there’s hardly any resemblance to the novel at all. My guess is that Moonraker was chosen simply because it had the word ‘moon’ in the title. It certainly made sense from a marketing perspective.

[on whether he knows Jaws] Not socially. His name’s Jaws. He kills people.

James Bond

Moonraker received mixed reviews upon release, many feeling that it strayed too far from the Bond template with its transparent genre aspirations. There’s no doubt that the film is wildly overblown, even by Moore’s brazen standards. In fact, for an actor who has been criticised for his tongue-in-cheek approach to Fleming’s irrepressible icon, Moonraker is a contender for the silliest entry of his tenure, and anyone else’s for that matter. The Bond series had been going that way ever since Sean Connery cracked America with 1963’s innovative blockbuster Goldfinger, a movie that veered away from the Cold War espionage of From Russia With Love and set the template for the next two decades. For Your Eyes Only, the sobering antidote to Moonraker‘s oddball decadence, would tread similar ground, returning the series to more serious territory, but Lewis Gilbert’s grandiose splurge went out with a deafening bang.

There is so much going on in Moonraker that it is sometimes hard to keep up. The film is a relentless whirlwind of blockbuster action, lavish locations and even lavisher special effects. It is somewhat bloated and haphazard at times, Eon attempting to squeeze as much science fiction into a typical Bond plot as they can, but it’s never less than fun and exhilarating, with gadgets galore, spectacular set-pieces and the kind of set design that still makes your mouth water. It may not feel like quintessential Bond at times, but you know exactly who and what you are dealing with for the most part. Its goofball antics can be darn endearing.

The film’s opening, pre-credits scene is Bond at its absolute best, our seemingly limitless super spy thrown ruthlessly from a plane before tussling with an airborne pilot and skydiving his way into a parachute. Except for the usual actor close-ups, the sequence was shot in freefall using helmet-mounted cameras, each jump lasting approximately a minute in total. Due to the insane process of capturing the two minutes of footage, the entire sequence would be repeated 88 times and would take a period of five weeks to complete. Just imagine that in today’s CGI-heavy climate, it’s unthinkable. Despite the post Star Wars revolution, Bond was still the main attraction when it came to elaborate stunts, and this one is truly breathtaking. Even the seeming demise of Jaws, suddenly cushioned by a circus tent, is just the right amount of silly, but that particular character will ultimately make the kind of transition that there is no coming back from.

One of the elements that particularly irks me when it comes to Moonraker is the handling of Richard Kiel’s once-monstrous creation, who, a toothy moment on the fringes of a carnival aside, comes across as less of a monster, more a lovable buffoon. Sure, Jaws was portrayed as something of a klutz in The Spy Who Loved Me, but his turn in that movie was largely fearsome, forging arguably the most memorable henchman in the entire Bond series. After that infamous moment in Moonraker when Jaws spies a peculiar, big-breasted girl with pigtails, everything changes, our once towering menace skipping gleefully into the proverbial sunset. It seems like an odd decision, but even stranger is the reason for the character’s sudden change of heart. Jaws was originally set to be Bond’s nemesis until the bitter end, but plans were scrapped after Kiel received mountains of fan mail from children begging him to turn into a “goodie”. It may not be to my personal tastes, but it is a fitting development for the real-life Kiel, a gentle giant who would remain one of Moore’s closest friends before his passing in 2014 (on a side note, did any of you remember Jaws’ squeeze Dolly having braces? A little research tells me that thousands of people imagined the exact same thing in what is the only instance of the Mandela Effect that I have personally ever experienced).

Such a development would prove the death knell for Kiel, this particular instalment marking the final appearance of Jaws. Luckily, Moonraker features a superlative villain in Michael Lonsdale’s exquisitely deadpan Hugo Drax, the billionaire owner of Drax Industries, a private company which makes space shuttles for NASA. Drax fits the classic megalomaniacal template to an understated tee. A former Nazi in Fleming’s Moonraker novel, he is one of the cruellest Bond adversaries in the entire series, a ruthlessly myopic sociopath with designs on committing global genocide from outer space, before replacing the population with genetically flawless specimens. If he’s not setting packs of wild dogs on helpless (and treacherous) secretaries, he’s attempting to incinerate James and his latest fling beneath the blazing propulsion engines of a space shuttle, recalling those elaborate, doomed-to-failure plots to eradicate the world’s most fortunate MI6 agent. British actor James Mason was initially set to play the character, but Frenchman Lonsdale won out in order to comply with the criteria of an agreement that made Moonraker an Anglo-French co-production, a decision that was taken to avoid England’s high levels of taxation.

Lonsdale certainly made the most of such a proviso, playing Drax with a haughty relish that is befitting of a culture vulture who proudly extols how every last stone of his California-based French château was imported from France, delivering classic Bond villain lines such as, “Mr Bond, you defy all my attempts to plan an amusing death for you,” and “Look after Mr. Bond, see that some harm comes to him.” There’s also the wonderful moment when he and 007 are out hunting pheasant (something a new-age Bond doesn’t seem to agree with). Initially, we’re aghast to think that the world’s deadliest spy has this time missed his target. Bond doesn’t seem flustered, and when a tree-bound sniper falls unceremoniously to his death, we understand why. “You missed, Mr Bond,” Drax goads before realising who was Bond’s true target. “Did I?,” Bond replies. “As you said: such good sport”. Nobody can pull off a smug punchline like Roger. This is classic 007.

[having just sent Drax hurtling into space] Oh, he just took a giant step for mankind.

James Bond

As you might expect, Moonraker is not without its flaws. When a film is rushed into production, there are bound to be casualties, and since Bond is essentially attempting to imitate another franchise (at least to a degree), it sometimes loses sight of some of its own staple ingredients. Take the time-honoured Bond girl. Ex-model Lois Chiles is almost completely forgettable as the unfortunately named Holly Goodhead, an astonishingly sexist moniker that is ironically the most memorable thing about her character. She is absolutely gorgeous, few actresses having ever looked better in the throes of zero gravity, but her role is crudely underdeveloped, and there isn’t much in the way of chemistry between she and Roger.

The Moonraker theme, performed by series Stalwart Shirley Bassey after a deeply frustrated Johnny Mathis pulled out mere weeks before the film was set for release, also feels like it was thrown together at the last minute. It is by no means the least memorable of the series. It is elegant, beautifully performed and very much in the classic Bond mode, with luxurious strings and a slightly more cotemporary sound, but it fails to catch fire like the most memorable of the series. It is certainly Bassey’s weakest entry, and ultimately her last.

Conversely, Barry’s score is typically majestic, a sumptuous ride with masterful cues that ranks as one of his finest. Moonraker would prove a turning point for the composer, who would record the score in Paris rather than London’s CTS Studios as was tradition. The fact that he made a concerted effort to move away from the Bassey-esque sounds of previous forays may go someway to explaining the theme’s somewhat unassured nature. Bassey’s overall output would wane during the 1980s, the vocalist releasing only three albums as she began working more behind the scenes as a vocal coach. By that time her sound had become somewhat outmoded, the series embracing the 80s synth revolution during John Glen’s tenure with unique and memorable performances from Sheena Easton, Duran Duran and A-ha. In some ways, the Moonraker theme was an awkward transitional step in Bond’s commercial evolution.

On something of a sombre note, Moonraker also marked the final appearance of Bernard Lee as ‘M’, who was already in ill health at the time of filming. The wily stage veteran had been a part of the series from the very beginning, his no-nonsense style making him a firm favourite among Bond aficionados. He was also highly regarded behind the scenes for his unwavering professionalism and a portrayal that stayed true to Fleming’s vision. Outside of Bond, the actor was regularly cast as a senior detective, projecting a moral resilience that is befitting of M’s profession, with an approachable façade that simultaneously endeared him to audiences. Lee was set to return in For Your Eyes Only though sadly passed away during pre-production.

If Bond is all about the spectacle, it is difficult to complain too much in regards to Moonraker. As well as featuring locations to die for, there are top-notch action sequences to rival the film’s opening, airborne salvo. Particularly impressive is a cable car scene high above the mountains of Rio de Janeiro, one that sees James and Goodhead tussle with a returning Jaws, with some death-defying stunts that almost spelled the end for real-life stuntman Richard Graydon, who actually slipped and narrowly evaded death during the kind of jaw-dropping spectacle that the series has become synonymous with. Equally enthralling is a rip-roaring river chase in the Amazon and a fully-loaded speedboat with gadgets aplenty, though in reality the scene in question began on the North Fork of the St. Lucie River at Jupiter, north of Palm Beach on Florida’s east coast, ending on the border of the Brazilian state of Paraná, the Argentine province of Misiones and Paraguay.

On the sillier side of things there is the wholly absurd but deeply charming gondola-come-hovercraft that cruises the affluent Piazza San Marco in Venice, Italy, the sight of an assassin appearing from a canal-bound coffin a particular delight for fans of Bond’s kitsch side. The film also suffers from something of a kung-fu hangover following The Man With the Golden Gun‘s high-kicking exploits, which were again designed to tap into the popularity of others, in this case cultural phenomenon Bruce Lee. This was less than a year after the release of Enter the Dragon and Lee’s sudden and unexpected death (Lee passed away prior to the release of his first Hollywood hit from a brain edema possibly caused by a reaction to a prescription painkiller). This results in a seriously anomalous kendoka battle with Drax henchman Chang that recalls Peter Sellers’ battle with Cato in 1976‘s The Pink Panther Strikes Again. It is a fantastic and particularly brutal battle with a spectacular climax, one that has the distinct honour of featuring the most break-away sugar glass ever used in a single scene.

I think he’s attempting re-entry, sir.

Q

In terms of pure grandeur, the movie of course saves the best for last. In typical Bond fashion, Moonraker is all about the final act, and Gilbert and his crew shoot for the stars. Plot-wise, it all gets a little messy as we’re sucked into a cinematic black hole of shallow extravagance, but you can certainly see where all the money went. British film and television special effects designer Derek Meddings was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Visual Effects for Moonraker, and deservedly so. The sight of a laser-strewn, celestial gunfight may seem at odds with the rest of the film ― and the series as a whole for that matter ― but it is an absolutely glorious spectacle, even if it’s all rather formulaic and meandering in a narrative sense. It’s best to abandon all hope for meaningful resolutions, to just switch off and soak it all up. The whole final act reminds me of an elaborate space ballet that makes as much sense as an Italian opera. And that can be a good thing, depending on how you receive it.

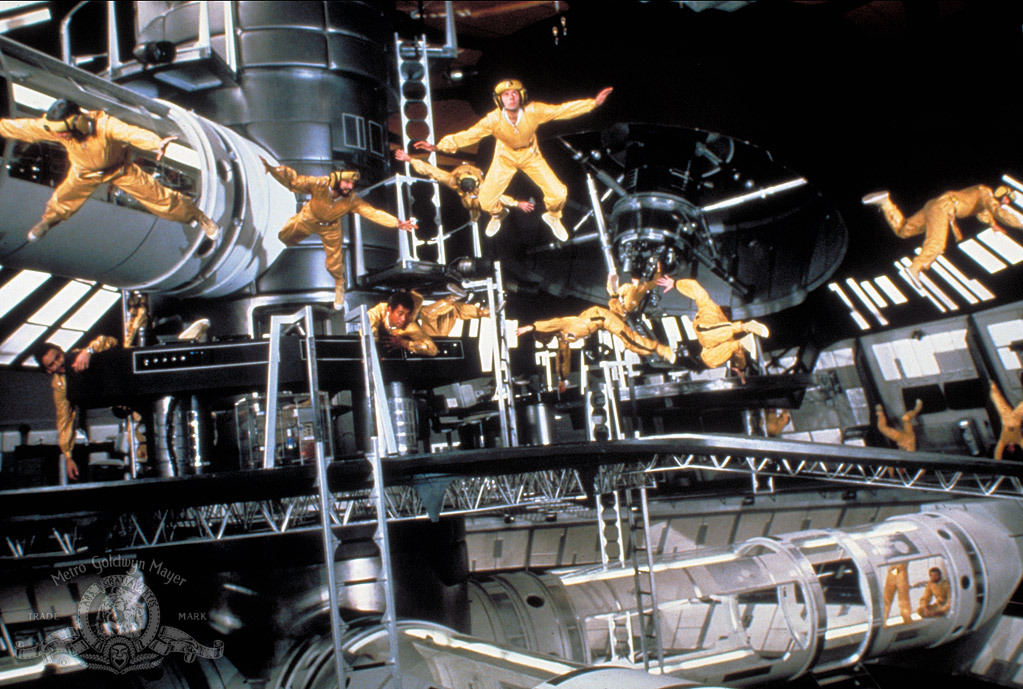

The set created for Moonraker, which like countless other sci-fi films was influenced by the revolutionary aesthetics of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, is a colossal work of structural art, one that still holds the world record for the largest number or zero gravity wires to be utilised in a single scene. The film’s monolithic sets, the largest ever constructed in France, required over 222,000 man-hours of intense labour, which approximates to 1,000 hours of work per crew member. You have to admire the scope, craftsmanship and sheer dedication that goes into creating such a spectacle.

You can see how Moonraker could be lost on some, especially those who aren’t particularly enamoured with Moore’s eyebrow-raising antics, the film’s sense of self-awareness revved up to delirious levels at times. Roger also received quite a bit of stick for his plethora of cheap puns and double entendre, and this particular instalment is positively alive with them. Whether it is ‘Q’s balls’, being ‘a little premature’ or ‘giant steps for mankind’, the sense of camp is strong with this one.

Ultimately, Moonraker irks many Bond traditionalists for attempting to be something that it’s not. I can see why. Adapting to the times is one thing, but such an innovative series shouldn’t have to ape commercial trends so transparently ― unless, of course, there’s a truckload of cash at stake, and studios are not in the habit of being sentimental when it comes to the moolah. I suppose those traditionalists can always take pride in the fact that most franchises would have been killed by such antics, but Bond is too ingrained in our culture, too universally beloved. Star Wars may possess the kind of world building that has its own gravitational field, but there is only one 007. Reams of blockbuster franchise characters have been and gone during Bond’s tenure, and will no doubt continue to do so, because in the end, nobody does it better.

Director: Lewis Gilbert

Screenplay: Christopher Wood

Music: John Barry

Cinematography: Jean Tournier

Editing: John Glen

I can’t believe I didn’t comment on this one here: well, anyway, we know why this particular Bond is styled this way (“Star Wars”). Um, I think it’s alright, and I do like that Jaws is back (and kinder, gentler too), Holly Goodhead (I believe I once mentioned on VHS Revival that I really liked Lois Chiles in ‘The Hitchhiker’ segment in “Creepshow 2”, so that kind of translated to this film; plus, the contrast in the Goodhead and Mrs. Lansing characters amuses me), I feel the last half-hour or so is fun, and I like the concept of Zero Gravity. Is it one of the better bond films? No, I wouldn’t say so, but I think I understand why it exists, and I’m okay with it.

LikeLike

Those are pretty much my sentiments. It’s all rather dissonant but I always enjoy it. It loses me plot-wise during the final act but it’s all very beautiful aesthetically. An unbelievable pre-credits sequence too.

LikeLiked by 1 person