Hitchcock’s hugely influential masterpiece remains a timeless, breathless classic

Psycho never ceases to amaze me. It amazed me when I first saw it back in the late 90s as a reluctant teenager — the kind who treated black and white cinema with the grave suspicion of a hypochondriac trapped in a doctor’s waiting room during flu season — and it amazes me now; more than ever. My initial reluctance to rent Psycho instead of the countless colour movies was not totally ill-founded. I’d been forced into black and white films before, usually bored on a dreary weekday afternoon, when mediocre throwbacks from the 1940s filled the TV schedule with all the dynamism of a wet tea bag. They were mostly war movies, sometimes comedy based, that reeked of obsolescence. They were mindlessly patriotic and wooden, technically primitive and lacking any real bite, and there were no streaming platforms to turn to for relief. We had five channels, so you took what you could, and one night Psycho just happened to fall into my lap like a crudely ditched blade at the scene of a crime. I was completely spellbound.

Ironically, and the reason why Psycho‘s rare endurance as a top tier horror film in the face of so much modern innovation still amazes me, is the fact that Hitchcock’s greatest achievement was considered, at least on the surface, to be from the past, a step back for a filmmaker who had embraced colour advancements long before. Black and white pictures still had legs in 1960, were in fact predominant to a lessening degree up until 1967, but previous classics Rear Window, Vertigo and North by Northwest had all been shot in gloriously modern, full colour. In fact, Hitchcock’s first colour movie, the Technicolor psychological crime thriller Rope, had been released way back in 1948, a year when colour films were much rarer. By 1960, Hitchcock was a highly successful figure in Hollywood who had worked with the era’s top stars and had massive sway with producers, but Paramount Pictures balked at the director’s usual budget demands when it came to Psycho, the premise, based on Robert Bloch’s novel of the same name, having already been rejected by studio readers for being “too repulsive” and “impossible for films”. The problem was, Hitchcock was contracted to another movie under Paramount.

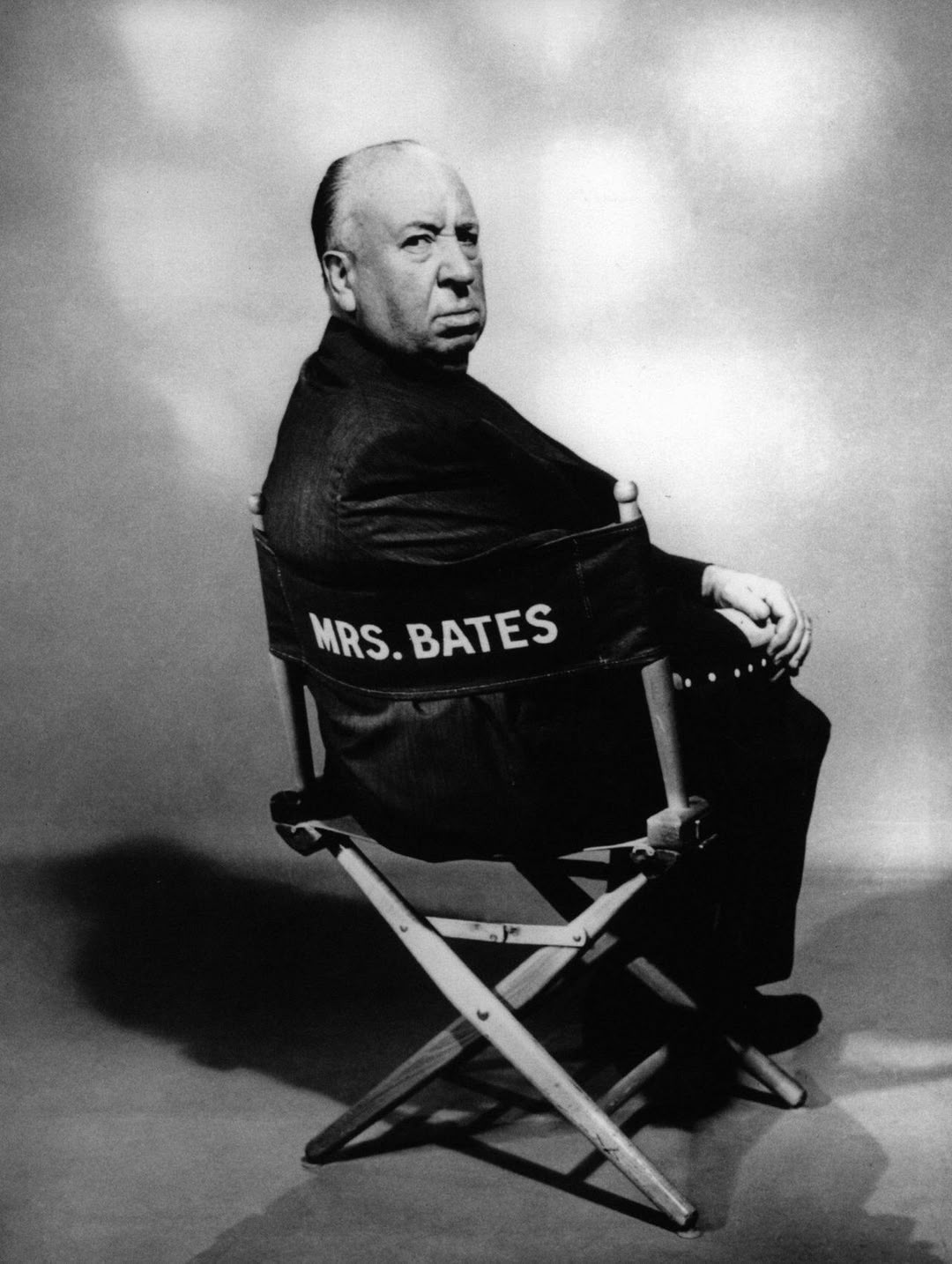

Paramount had thrown a spanner in the works, but Hitchcock was a strong, determined personality who had boundless self-belief in his latest project, even after his two previous efforts with the company, Flamingo Feather and No Bail for the Judge, had been unceremoniously aborted, the latter after star Audrey Hepburn had fallen pregnant. Undeterred, Hitchcock pushed to get Psycho made any which way he could. He initially proposed that he would shoot the movie cheaply in black and white using the crew from his hit television series Alfred Hitchcock Presents, but Paramount had no intention of funding it whatsoever, only succumbing to Hitchcock after he agreed to fund it himself, the filmmaker eschewing his usual fee under the proviso that he would own a 60 percent stake in the film’s negative. Like many of the greatest works of any medium, few saw the value in Psycho beyond its creator.

Back in 1960, the concerns of Paramount regarding Psycho, particularly its violent and sexual content, were hardly irrational. With its psychosexual nature and what, thanks to some deft editing by George Tomasini, was the most realistic portrayal of murder ever captured on film, the moral furore surrounding the movie was immediate. Bear in mind, this was a time when it was controversial to show a toilet onscreen, another reason for the ire of moral naysayers when it came to Hitchcock’s most daring film. Go back and watch the actual act of stabbing during the movie’s iconic shower scene. Using extreme close-ups and rapid-fire cuts, Hitchcock and Tomasini create an ultra-realistic death that has more of an impact on the imagination than any modern CGI indulgence. You never actually see the blade penetrate but it sure seems that way. There was, and never will be, a more powerful tool than the imagination of a watching audience.

I think that we’re all in our private traps, clamped in them, and none of us can ever get out.

Norman Bates

The graphic nature of Psycho had the potential to make a villain out of Hitchcock, but money talks, and just like Stephen Spielberg, who in the mid-1980s had the pull to have the PG-13 rating introduced to ease the commercial burden on projects Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom and Gremlins, Hitchcock came up trumps. Inevitably, the critical consensus hammered Psycho for its lewd subject matter, but audiences went crazy for it, the movie raking in a whopping $50,000,000 ($384,500,000 when adjusted for inflation), on a budget of only $806,947, $30,000,000 of which went straight in Hitch’s back pocket. It was also nominated for four Academy Awards, including Best Director for Hitchcock (the members of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) don’t have the best record when it comes to handing out gongs to films that are daring, controversial and ahead of their time). Psycho‘s success can in part be attributed to the filmmaker’s creative genius and keen commercial foresight, but despite its stature as one of the most analysed films in all of cinema, influence and rub are always a factor. You only have to look elsewhere to see that.

Michael Powell’s lurid proto-slasher, Peeping Tom, another innovative psychosexual thriller released two months prior to Psycho, was banished to commercial purgatory for its similarly unseemly indulgences, only surfacing in the US after superfan Martin Scorsese paid for a print to be brought to the 1979 New York Film Festival, nineteen years after the film’s initial release. Former industry darling, Powell, would later attribute Peeping Tom‘s downfall to strained relationships with powerful people. “I had a lot of enemies in the higher echelons of the British film industry and they used the initial reaction to Peeping Tom against me,” Powell would recall. “A lot of people thought I was a pain in the neck, always wanting to do something new, sometimes proving them wrong—occasionally proving them right! But for a long time Peeping Tom made it impossible for me to get any film produced in England.”

The fact that Peeping Tom was not only shot in colour, but in affordable, “single-strip” Eastmancolor, a process known for its garish aesthetics, probably didn’t help matters. It’s not that the processes used to simulate fake blood looked particularly realistic back then, but even Hitchcock, whose decision to shoot in black and white extended beyond the budgetary, felt that colour would be too much, too soon, for use in the shower scene. Instead using black and white to his advantage, Hitchcock famously landed on Hershey’s chocolate syrup, which had a more realistic density than stage blood, and it absolutely saves one of the most ingeniously executed sequences in cinema from the inevitable horrors of obsolescence. Just imagine that scene in full colour. Primitive stage blood often takes you out of the moment in classic movies that are in many ways timeless. Some films are just destined for greatness it seems.

For all the hubbub surrounding Psycho‘s most iconic scene, it is now regarded as one of the greatest horror movies ever produced, and, ironically, it is in no small part because of that scene. There was a time when the shower scene worked as pure controversy, but more than a half century after Psycho‘s release, the sight of an undressing Marion Crane, the once graphic depiction of murder itself, committed while the victim is at her most vulnerable and exposed, and yes, even the sight of an onscreen toilet, are no longer grounds for contention. In fact, they’re so far beyond quaint, at 43 years of age I can hardly believe it myself. The scene holds up so well because of the sequence of shots leading up to, during, and after the act of murder, which were so masterfully constructed and dynamic for the time that they still have the power to mesmerise.

The murder itself, committed during an act of self-cleansing from the guilty and newly noble Marion, is swift, frenetic and disorientating, or as Hitchcock himself would explain, shot and cut “staccato, so the audience won’t know what the hell is going on.” The defensive shots of Marion (in reality actress Anne Dore) were shot at a lower framerate and sped up after the fact, such was the meticulousness and attention to detail in making the attack appear genuine. And why do some of those knife ‘penetrations’ look so real? Hitchcock began the shot with the knife touching the skin, the implement then pulled back and the film reversed to simulate an actual stabbing motion. That’s not to mention the ingenious sound effects (achieved by hacking a watermelon) and one of the most urgent and affecting scores in all of cinema. It was unlike anything anyone had ever seen.

Though the score for William Friedkin’s The Exorcist, (a combination of Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells and avant-garde pieces by Krzysztof Penderecki), and John Carpenter and Alan Howarth’s DIY Halloween score are certainly contenders, Bernard Herrmann’s Psycho score arguably remains the most memorable, affecting and omnipresent in horror movie history. Hitchcock immediately agreed, almost doubling Herrmann’s fee upon hearing it and later admitting that, “33% of the effect of Psycho was due to the music”. Experiencing the movie yet again just recently, it’s difficult to argue. The shower scene of course gets all the plaudits with it’s sudden, shrill urgency, but in reality it is the massive payoff to the almost relentless tension that precedes it, during which very little happens in the traditional horror vein. We get the pursuing patrolman and the confounded car salesmen who only furthers his suspicions, but Herrmann’s orchestral nerve-shredder is the movie’s pulsating heart almost from the get-go.

Modern audiences weaned on violent indulges may see the action as somewhat drab by comparison. After the slasher, which Psycho was certainly a progenitor for, was genericised following 1980’s commercial eureka Friday the 13th, it was all about ‘who can top this?’ bloodbaths, and CGI has only increased the grotesque possibilities in recent years, but whether it’s the sudden, almost surreal slashing of private dick, Milton Arbogast, or the movie’s shocking psychosexual reveal in the Bates basement, Psycho chooses its moments cannily, executing them swiftly and superbly.

Always the voyeur, Hitch of course gives us of plenty of time to dwell, both during and after the movie’s most violent sequence, a seemingly innocent Norman later arriving at the scene with a theatrical disbelief that puts us firmly in his corner as nothing more than a scared and unwilling accomplice. As shocking and as disorientating as the attack may have been to audiences who still viewed bikinis as taboo, it pales in comparison to the aftermath — the stream of blood trickling down the plughole, slickly transitioning to that deathly rotating eyeshot — which remains a deeply disturbing experience, thanks in large part to the ingenuity of its execution. Part of what makes the image of a lifeless Marion Crane so unsettling is the way in which it was achieved. If you have ever wondered how on Earth Janet Leigh could have remained so still and unflinching while posing dead in extreme close-up, the answer is the use of an optical printer spinning a freeze frame, seamlessly giving way to regular motion as the camera zooms out. The results are deathly.

Famously, that is the last we see of Marion Crane, even though her image adorned the promotional poster. Another reason why Psycho proved so shocking back in 1960 was the fact that Hitchcock, who resented the influence and demands of actors who he viewed as pawns in a game of chess, killed off his marquee star halfway through the movie (46 minutes and 40 seconds to be exact). Not only was this a display of mocking hubris from the filmmaker, it was a powerful narrative tool that toyed with audience expectation. Pretty much all the rules have been broken well into the 21st century, but there were certain safety nets in place back then, elements that viewers could count on to stop their vicarious horror experience from going south.

The main one was of course the survival and triumph of a film’s protagonist. Killing off a marquee star halfway through a movie was unheard of back in 1960. It didn’t make sense on so many levels, but that was what made it so impactful. If the star performer could die so soon into its running time, what could audiences expect from the rest of the movie? The floodgates were wide open. As part of the film’s promotion, a totally sincere Hitchcock famously proclaimed, “It is required that you see ‘Psycho’ from the very beginning!”, turning away tardy punters and explaining that “late-comers would have been waiting to see Janet Leigh after she had disappeared from the screen action.” The fact that Marion had already succumbed to her conscience by that point, had in fact planned to return arrogant slimeball Cassidy’s stolen $40,000 before anybody was the wiser, made the loss of the movie’s marquee star all the more unsettling at a time when notions of right and wrong were typically stamped in black and white.

The same moral grey areas are explored in regard to Norman; a meek, seemingly harmless young man under the rule of his dominant and demanding mother when we first meet him. The late Anthony Perkins, only 27 while Psycho was being shot, delivers an absolute tour de force in the role that would define him, offering the kind of nuanced performance that was much rarer back then, particularly for such a low-budget outing. He alternates between the wholesome and the mildly sinister with such acuity and swiftness that you are rooting for him right up until the movie’s shocking reveal, which is absolutely key to our involvement following the death of the film’s marquee star. Marion’s plucky sister Lila (Vera Miles), takes her place as the movie’s female lead, and was actually the lead protagonist in Bloch’s novel, but until we are hit with the most unlikely of truths, Norman is for all intents and purposes Psycho‘s protagonist for a good chunk of the movie, and ultimately the movie’s true star.

I think I must have one of those faces you can’t help believing.

Norman Bates

Though Psycho stays largely true to Bloch’s novel, many elements were altered when it came to Norman in order to make him a more sympathetic character. The version of Bates found in the novel is an overweight, middle-aged alcoholic who is very obviously unstable from the outset, adorning the guise of his mother while drunk, which would have killed the onscreen version of the character, his brief yet fascinating relationship with his latest victim, and the impact of the movie’s dramatic twist. Instead, the filmic Bates appears to be timid, naïve and, the occasional defensive outburst notwithstanding, relatively harmless, particularly in a more patriarchal society . He is also kind, compassionate and willing to go out of his way for Marion, who he seems genuinely smitten with and even impressed by. In hindsight, there are red flags everywhere, not least Norman’s incredibly creepy living quarters and the even creepier hobby that adorns the walls. But even after Marion is killed, Norman is presented as a victim of his mother, a curious peeping Tom ruined by a matriarchal witch. We don’t see the deranged killer with the dual identity, just a put upon victim weighed down by the burdens of familial circumstance.

Contrarily, Marion is the criminal up until the moment that she fatefully stumbles upon the indomitable Bates Motel and its seemingly gentle, good mannered proprietor, hounded by the suspicious lawman and questioned by the car dealer in a relentlessly tense first act that sees her wrestling uncomfortably with her conscience, even if the rube in question deserves to be 40 grand lighter. The amount of tension that Hitchcock achieves before Marion reaches the comparatively safe hideaway known as the Bates Motel, relying mostly on the filmmaker’s trademark distrust of authority, is palpable. Her reasons for stealing are relatively noble too. It’s not a question of greed but of desperation, their marriage and potential life together derailed by her beau’s insurmountable debts. As an audience, particularly in 1960, this was a typical setup, one that you would have expected to be resolved by Hitchcock and the film’s star at the conclusion of Psycho.

But Marion has a change of heart, and it’s mostly down to the naïve and gullible kid who only seems to have kindness in his heart away from the oppressiveness of his domestic predicament. Norman, or at least the Norman that Marion’s host chooses to portray during their time together, indirectly shows her the light, their earnest talk leading her to make the correct moral decision at the very last moment, something that makes her swift and sudden murder all the more devastating. Marion is thinking clearly when the two part ways seemingly forever. A few curt and off-colour replies notwithstanding, the kind that we naturally attest to his strict upbringing, it is only after Norman retreats to his voyeuristic spyhole that we begin to question his intentions, but even the act of spying remains borderline understandable given his oppressive domestic predicament. Perkins gives a career-best performance as the conflicted, complicated and deeply deranged Norman. In an era of comparatively one-note performances, his is nuanced, believable and utterly engrossing; another reason why a movie with a B-movie budget achieved such prestige levels.

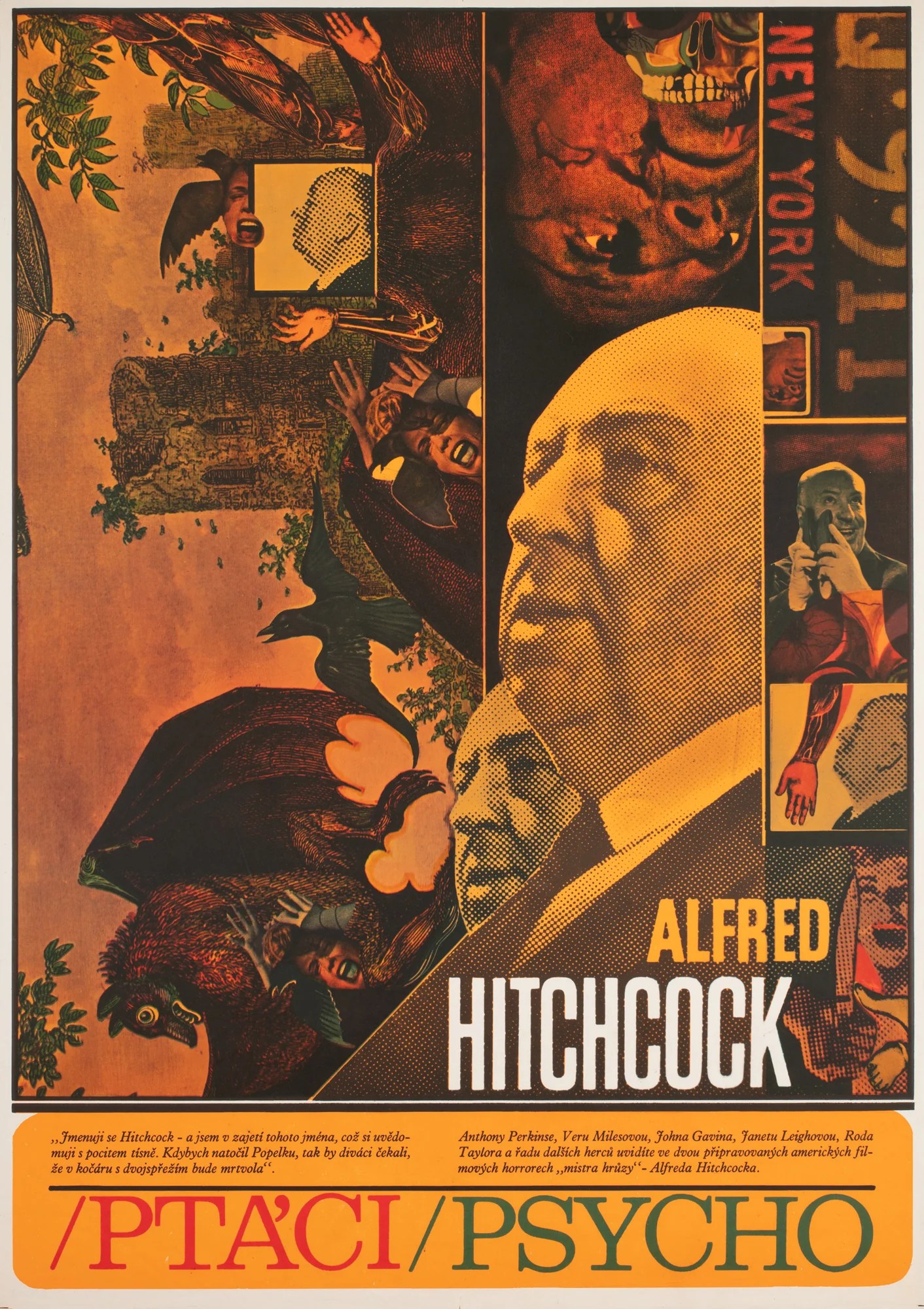

1960 was a landmark year for horror as the genre shifted from Hollywood to Europe, from 50s red scare McCarthyism involving fantastical monsters, to themes that were more real and relatable. The aforementioned Peeping Tom, Mario Bava’s Black Sunday and Georges Franju’s Eyes Without a Face would all break boundaries as the genre veered towards the sexual and psychological, but commercially speaking, for reasons that are obvious and otherwise, Psycho was the most prominent in spearheading that generational shift. It is a movie with its own gravitational field that is studied and continues to influence filmmakers to this very day. In an era of numbered sequel ubiquity, the colossal Perkins would inevitably return as the lead in the superb Psycho II, a short-time pariah which framed Norman as the protagonist from the get-go, and again in the more shameless, straight-up slasher Psycho III, and, lest we forget, Mick Garris’ atrocious, made-for-TV effort Psycho IV: The Beginning, which, try as it might, did little to sully the legacy of both Hitchcock’s most famous work, and the actor who personified it so indelibly.

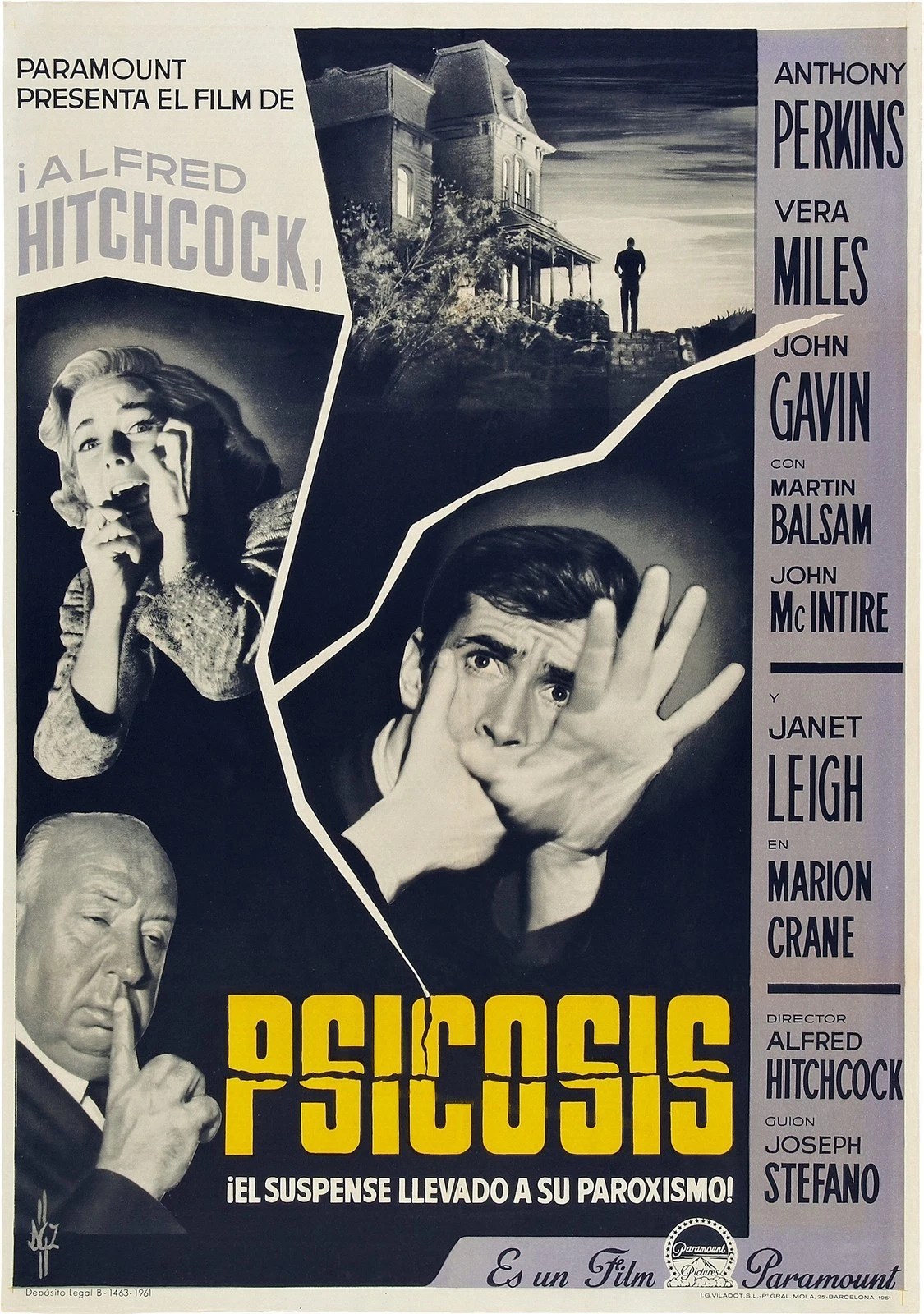

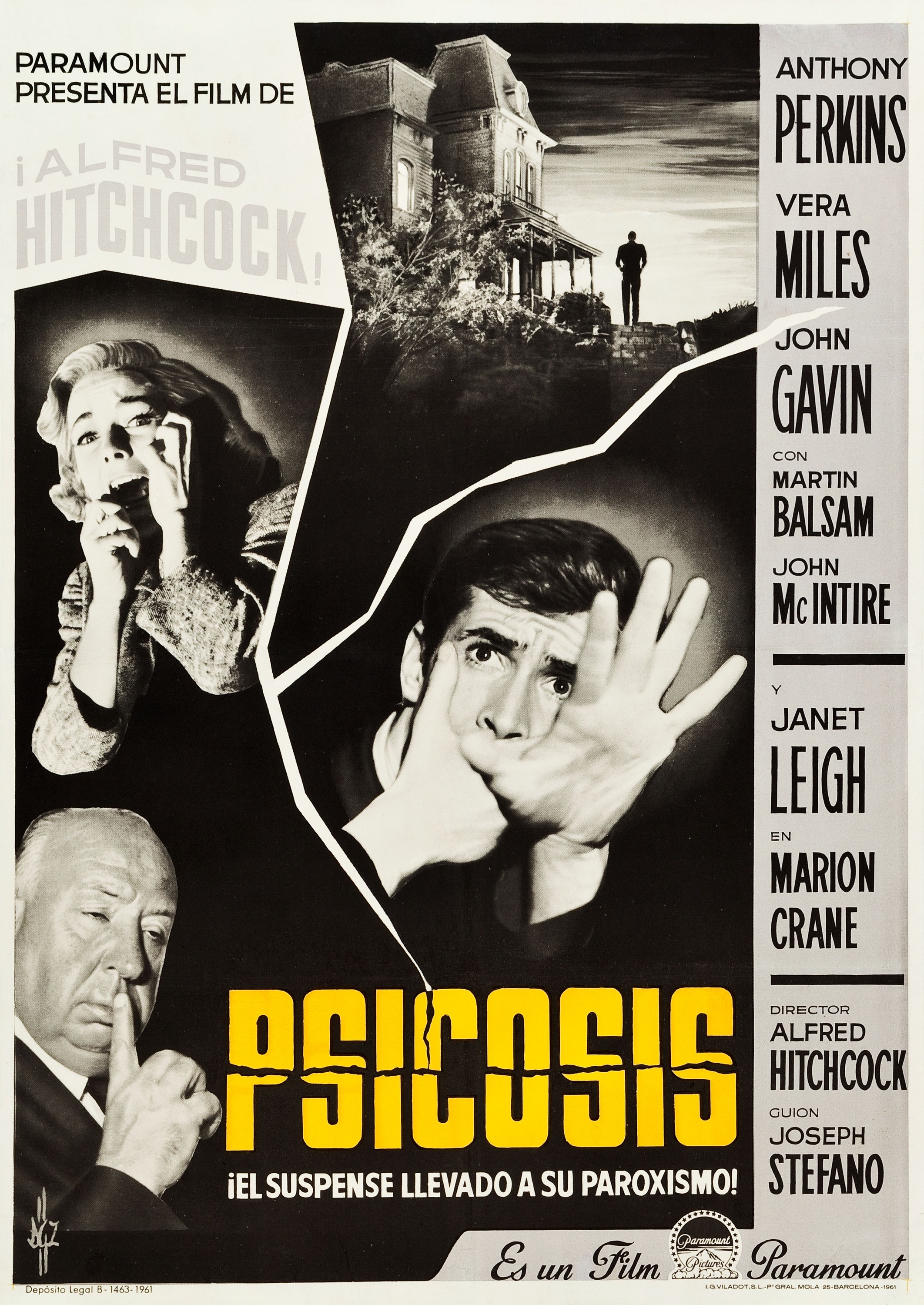

Director: Alfred Hitchcock

Screenplay: Joseph Stephano

Cinematography: John L. Russell

Music: Bernard Herrmann

Editing: George Tomasini

Psycho is such an enduring horror classic and ultimately Hitchcock’s masterpiece as well. The ripples of its impact are still felt today, and it shaped the genre in a way few could’ve ever imagined. Fantastic write up, always enjoy these classic retrospectives so much 🙂

LikeLike

Thanks, Paul. Always great to hear from you. I consider you our biggest fan. It’s been a while since my last one, as I’ve been feeling a little under the weather, but with its 65th anniversary approaching, I felt that it was time to cover, what is, as you say, Hitchcock’s most influential work.

The unrelenting tension and the shower scene payoff is still absolutely breathtaking. And what about that score?! Is it the most famous of all?

I want to revisit the brilliant Psycho II, and even Psycho III, which is entertaining if a little tasteless. I don’t think I have the strength for Psycho IV though. 😁

LikeLiked by 1 person

HI ya! You are too kind. Cheers mate, always enjoy visiting you blog for the new posts. Hope you are feeling better soon as well. I’ve not posted quite as much recently as I’ve been busy and my dad hasn’t been too well either. So had to juggle my time a bit the last couple of months. Oh yeah, Psycho is such an iconic film, great way to celebrate its 65th anniversary, that score alone is worth the price of admission to see this film! Hope you revisit Psycho 2 & 3 eventually. Psycho 2 is brilliant, love that film as well, and THAT ending! Blimey, was sceptical about any Psycho sequel but that played a blinder with that one.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sorry to hear about your dad. Hope you’re both doing well. Psycho II was considered sacrilege at the time. People wrote it off before it had even screened. Man, were they wrong! Tarantino is a massive fan I believe.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Cheers. Yeah, he’s on the mend now so doing much better thanks. KWYM, I think Psycho 2 wasn’t something people really wanted, or even considered possible at the time, but its certainly proved people wrong. It’s a superb film and more than a worthy sequel to the original – not something that can be said often nowadays. Yes, I believe Tarantino is a big fan of it as well. Keep up the great work. Will look forward to Psycho 2 if you cover it.

LikeLike