Martin Scorsese’s underappreciated black comedy continues to grow in relevance

It’s hard to imagine how audiences would have reacted to seeing Martin Scorsese’s satirical black comedy The King of Comedy back in 1982, though the fact that very few did, at least during its initial theatrical run, speaks volumes. Cinema is typically a form of escapism, a vicarious thrill ride that allows us to indulge in emotions that are perhaps too exhilarating for everyday reality; you want to witness the blood-splattered gunfight or flee the gruesome monster, safe in the knowledge that no real harm will come to you. Sometimes you long for romance, for drama or comedy, the latter typically an outlet for fun and good times, but there’s nothing fun about The King of Comedy, no good times to be had in the purest sense. Any laughter you may experience will come with a large side of eye-popping incredulity.

Despite its comparative lack of popularity in the Scorsese oeuvre, The King of Comedy is a damn fine movie. It is bold, uncompromising, and completely against the grain. It doesn’t have the devastating impact of earlier Scorsese classics like Mean Streets and Taxi Driver, because despite teasing the same kind of explosive payoff, the movie ends on an unexpected, and in some ways more interesting note, one devoid of bloodshed or complete psychological breakdown and the consequences that generally come with it, something that the film’s protagonist, and his equally unhinged partner in crime, seem to beg for. The King of Comedy also lacks the cinematic beauty and emotional gravitas of the director’s previous outing, the warts and all boxing biopic Raging Bull, which though still somewhat lenient in its depiction of the sociopathic Jake LaMotta, pulls few punches in its unravelling of one of boxing’s meanest personalities.

Scorsese had considered retiring from making feature films following Raging Bull, his decision to concentrate solely on documentary filmmaking halted only by the idea of passion project The Last Temptation of Christ, which in turn was halted by frequent Scorsese headliner Robert De Niro’s disinterest in playing Jesus Christ. Though The Deer Hunter‘s Michael Cimino was originally tied to The King of Comedy, his protracted involvement with the editing process of his commercially doomed epic western Heaven’s Gate and De Niro’s desire to tackle comedy, a genre that he would prove just as adept at, saw Scorsese returning to the fictional fray. With documentaries still on the mind, Scorsese decided to step away from the pure elegance of Raging Bull in favour of a rawer style that was in-keeping with visually expressive pre-talkies cinema, taking particular influence from Edwin S. Porter’s Life of an American Fireman (1903). Interestingly, inimitable comedian Andy Kauffman was initially considered for the Pupkin role prior to Scorsese’s involvement.

Ultimately, The King of Comedy benefits from a relatively small, finely tuned cast; particularly the ever brilliant De Niro, who under the filmmaker’s tutelage became arguably the greatest screen actor of his generation, and possibly any generation. De Niro is totally believable as nutso, monomaniac kook Rupert Pupkin, a polite, seemingly congenial upstart comic with a deeply troubled core that, crucially, he remains totally unaware of. Though almost completely disconnected from reality and responsible for some severely distressing behaviour, you never feel truly threatened or repulsed by the character’s presence. A lesser film may have portrayed him as an evil maniac, but he doesn’t mean anyone any serious harm in his ruthless, seemingly misguided approach to attaining superstardom, De Niro doing just enough to keep the audience onside. Self-delusion is often the key to success, and as events bizarrely play out in The King of Comedy, that is very much the case with Pupkin, who against all odds will one day fulfill all of his aspirations and then some.

Better to be king for a night than a schmuck for a lifetime.

Rupert Pupkin

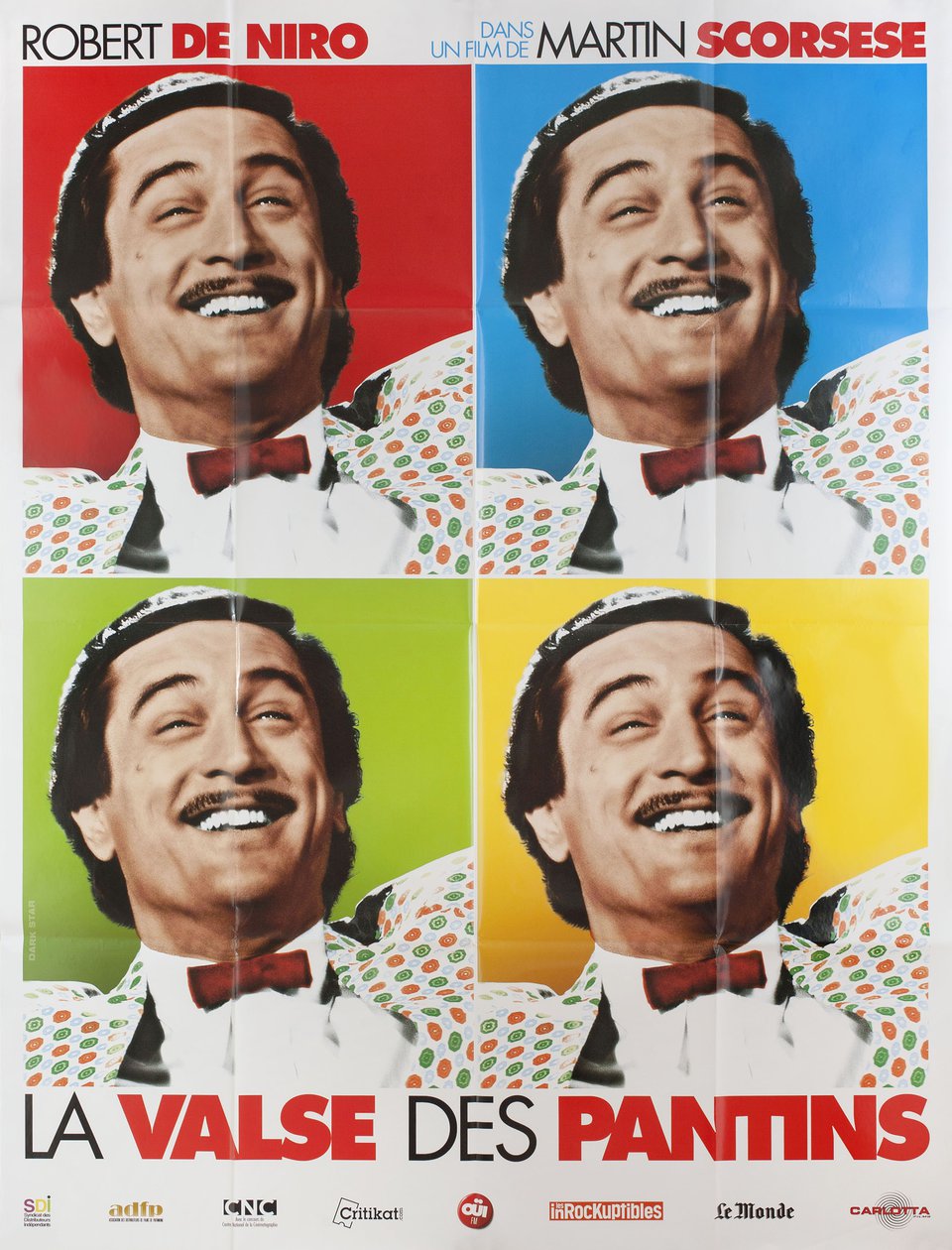

Further levity comes from the way in which the Pupkin character is presented. Despite his deeply troubling obsessions, the kind that a book of hungrily hunted autographs from days past allude to even further, Pupkin is smiling, energetic and dapper, irresistible in his unwavering positivity and sense of ambition, even in his darkest moments. Like many oddball loners Pupkin still resides in his mother’s basement, a shrine to the fantasy allure of superstardom which drowns out his mundane existence, and even the nagging voice of his disapproving mother like the exhilarated audience at a star-studded event, the kind that rings in his imagination on a daily basis. His underground hideaway is basically an office-come-studio, complete with full-sized, immaculately positioned cut-out guests, a residue of his latest and most ambitious target: the top-rated, late night TV host and comedian Jerry Langford (Jerry Lewis). In one particular fantasy, Langford goes to great lengths to compliment Pupkin as the next big thing, pegging him as a talent that he can’t possibly live up to. A moment when the imaginary Langford playfully yet aggressively rubs his hand all over Pupkin’s face, crudely obscuring his features, is an inspired visual insight into our sick protagonist’s screwed-up psyche.

Always a stickler for detail, De Niro once again went that extra mile in his admirable quest for authenticity. The King of Comedy didn’t call for anything quite as extreme as the 60lb weight gain that went with La Motta’s incredible fall from grace in the final act of Raging Bull, but there was no less of a commitment on his part. As well as the more typical procedure of hanging around with and learning from characters who are similar to those that he portrays, the actor embraced an unusual “role reversal” technique that consisted of him pursuing obsessive fans with similarly obsessive questions about their life and intentions. According to Scorsese, he even agreed to have dinner with his own stalker in order to understand their motivations, which is presumably where Pupkin’s delusions of dining with luminaries such as Langford came from. In one particularly cringy scene, De Niro takes a date to Langford’s home under the pretense that they’ve been invited to a star-studded dinner, which to her embarrassment proves to be a total lie. Langford pulls no punches in his rebuttal, happily admitting to being dismissive of the likes of Pupkin. Not because he’s famous, but because fame, and obsessives like Pupkin, generally dictate as much.

Lewis, who was the prime Jim Carrey of his day, a rubbery bundle of fun with tireless energy who wowed audiences with his frenetic performances, is inspired casting as the oppressed by fame, borderline curmudgeon Langford, who becomes an almost inanimate ogre as events play out. The character was originally imagined as a self-absorbed hypocrite and 24-hour telethon host, mirroring Lewis’s own annual charity exploits, but Scorsese’s Langford is a more sympathetic character whose daily frustrations are more than anyone should have to deal with. The trappings of celebrity are abundant and well documented in an era of reality TV and social media abuse, but were perhaps more of a revelation back in the early 1980s. Not only is Langford expected to be in character at every waking moment on the New York City streets, cracking jokes with well-meaning cabbies and serenading tribes of boisterous workmen, he’s expected to fulfill every fan’s whim, like the woman who wishes cancer on him when he refuses to stop and speak to her sick relative – not the most demanding request as a solitary incident, but this is every day, all of the time. People feel that they know Langford and automatically expect something in return. And, scariest of all, this is the least of it.

Pupkin’s lady friend, ‘queen’ Rita Keene, played by De Niro’s then-wife Diahnne Abbott, provides yet more insight into Pupkin’s obsessive mind and stubborn refusal to not only take no for an answer, but to exhibit any kind of self-awareness. And he’s certainly not dumb to what he is doing, staying one step ahead of the FBI’s attempts to trip him up while Langford is being held hostage by his even more unstable partner in crime under the proviso that Pupkin is allowed to not only perform on his show, but to see that performance aired at the bar that Keene tends.

Pupkin has his heart set on Keene, yet another obsessive outlet in a life that is completely motivated by them. When he first shows up at the bar, she barely recognizes him. He’s merely a vague face from the past, but he is insistent, charmingly so, offering her the heady heights of fame and fortune, claims that result in nothing but a wry smile and perhaps the faintest hope that she might escape the drudgery and monotony of her everyday existence. She knows there’s something off about Pupkin, but she never once seems threatened. Even during his more extreme moments she views him as strange but harmless, and, considering the amount of time she allows him, is perhaps naive to the fact that he is a complete fantasist. Or, if the movie’s conclusion is anything to go by, is perhaps subconsciously aware that Pupkin might just be crazy enough to succeed.

I’m gonna work 50 times harder, and I’m gonna be 50 times more famous than you.

Rupert Pupkin

The movie’s other ace in the hole comes in the form of Sandra Bernhard’s fellow Langford fanatic, Masha. Unlike Pupkin, Masha is definitely someone you should worry about. From the moment she throws herself at Langford in the backseat of his limousine during the film’s hectic opening moments, all flailing claws and hellacious screams, it’s clear that there is something seriously wrong. Unlike Pupkin, there is no real endgame to her madness. She simply wants to possess Langford, to own him, to chain him up and love him, or at least project upon him her twisted, abstract idea of what love is. Masha is deeply wounded, completely unpredictable and vicious in the pursuit of her misguided lusts. It’s no wonder that the movie’s most iconic scene, the one that has been parodied the most throughout the years, belongs to Bernhard. She threatens to steal the show at times.

Ultimately, Pupkin feels like less of a threat because, despite inhabiting the same fanatical realm as Masha, he at least has a goal in mind, a purpose behind the madness, and at the end of it all he is accepted as something of an antihero. After being tried for his crimes, he releases a “long-awaited”, soon to be best-selling biography, King for the Night, and is weighing-up several “attractive offers,” including comedy tours and a film adaptation of his memoirs. He even takes to the stage for a TV special, where he is greeted with great enthusiasm by a live audience, proving that, despite crimes that might be considered unhinged, people are willing to accept pretty much anyone with a unique story to tell. And, against all expectation, Pupkin is a half-decent comic. He certainly has Langford’s audience in the palm of his hand, especially when he admits to kidnaping their absent host, which they naturally presume is simply a part of his act. It’s no wonder that the movie has been compared to Todd Phillips’ controversial Joker, which even features a wink wink cameo from De Niro himself.

Like many situations in life, acceptance is key here. It’s the only thing stopping Pupkin from being pegged as a creep and a madman, which speaks to the fickle nature of celebrity culture and those who worship at its alter. Is Pupkin’s pursuit any different from that of multi-winning artist Kesha, who once broke into Prince’s home in a desperate attempt to get her demo in front of him? Sure, Pupkin goes to more extreme measures, and if someone of his description was found on Prince’s property, it’s unlikely that he would have been quite as receptive, but would Kesha have given up had her initial advances been dismissed, or would she have taken it further? Ambition is a powerful drug. There are simply no limits as to how far some will go in order to achieve their goals.

Despite being responsible for some of cinema’s finest movies, Scorsese wasn’t always a smash at the box office thanks to his indie spirit, the filmmaker resorting to studio pleasing movies on occasion to get producers back onside. The King of Comedy absolutely bombed at the box office, and many disregarded it as a consequence, but today the film feels even more relevant as a commentary on the pursuit of the American dream, in becoming a celebrity at all costs. Pupkin is punished, rather leniently, for his crimes, serving just over two years of a six-year sentence, but the warped, often unscrupulous world of celebrity adoration accepts him anyway. Before his rise to overnight superstardom, Pupkin’s name is often mispronounced. It, surely intentionally, sounds a lot like pumpkin, and in many ways The King of Comedy is something of a Cinderella story, but Pupkin’s carriage doesn’t turn into pumpkin. It takes him, rather unexpectedly, all the way to the top. And if the people love him for it, what else matters?

Director: Martin Scorsese

Screenplay: Paul D. Zimmerman

Cinematography: Fred Schuler

Music: Robbie Robertson

Editing: Thelma Schoonmaker