Director: Fred Olen Rey

18 | 1h 31min | Action, Horror, Sci-fi

Deep Space is simultaneously one of the best and worst Alien rip-offs out there. Think MacGyver meets Aliens – a blockbuster sequel released two years prior whose lasting popularity the film looks to tap into (on a much smaller scale, obviously). I say best and worst because if you were flipping channels and happened to catch the movie during one of its more innocuous moments, you might mistake it for an episode of Cagney and Lacey or the multitude of terrestrial cop shows flooding TV schedules during the 1980s. If, however, you managed to catch it during one of its more overtly derivative moments, and were severely (like three bottles of scotch) drunk, perhaps with one eye closed and half of your attention on the phone call that just awoke you from your inebriated slumber, you may momentarily mistake it for the real thing, especially when it employs similar lighting effects to Ridley Scott and James Cameron in an attempt to both obscure and galvanize the movie’s cheapskate visuals.

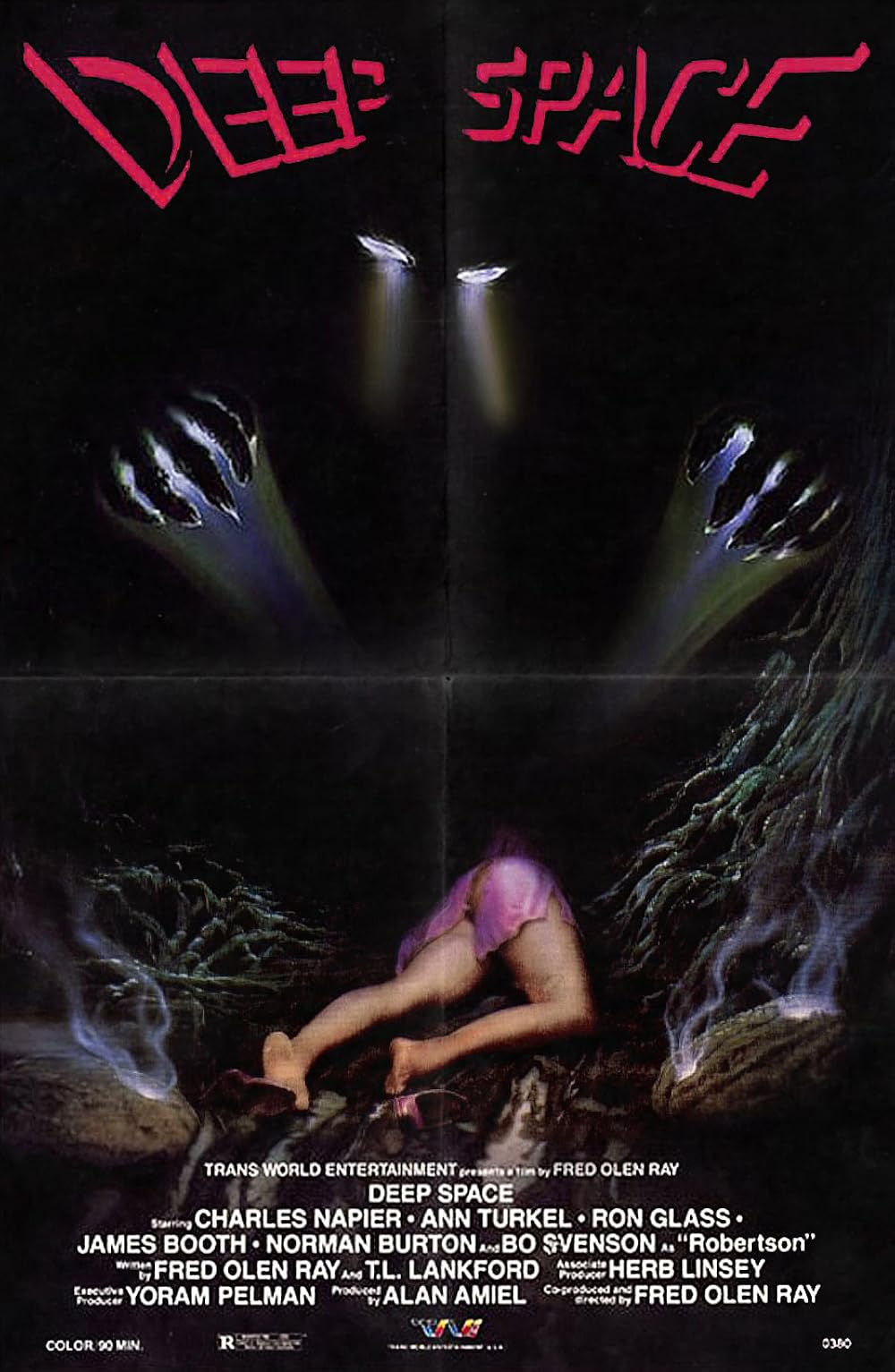

Such effects make sense in the bowels of a damaged, malfunctioning Nostromo; not so much in the murky concrete isles of the kind of abandoned factory that cash-strapped B-movies generally rely on for that all-important finale, the kind that seem to exist for the sole purpose of producing inordinate amounts of steam and incongruous swathes of neon. Deep Space needs those cheapjack tricks more than most. I’ve seen worse imitations of the xenomorph, and there are plenty out there, but the very act of imitating arguably horror’s most fearsome creation is enough in itself to inspire derision. You could come up with something almost as good, or even marginally better looking aesthetically, and it would still be cause for scorn were you to stick to that visual template so closely. One of Hollywood’s most terrifying, timeless designs is as instantly recognizable as Frankenstein, Michael Myers or even Batman. You can’t look to imitate these characters so transparently and expect to be greeted with even a modicum of seriousness.

Superficially speaking, Fred Olen Rey’s audacious punt at plagiaristic infamy and its blueprint, Alien, can be very much alike, but on the whole Deep Space is a seriously deceptive title. A blanket of stars during the movie’s opening credits is as close to celestial as we get, and aside from a blazing ball of fire in the sky and the laughable crash site of our invading creature, there isn’t much of a spaceship to speak of. Most of the movie takes place in or around your typical 80s cop precinct and is brimming with the usual stereotypes. We have a no-nonsense, rule-shy detective and his trusted token partner, a police captain who constantly pecks away at them, reminding us at every opportunity that they do things by the book (Bye book!), and a ditzy dame whose only purpose is to get high on the pheromones of the precinct’s undisputed alpha.

Against all odds, Napier is incredibly likeable as the borderline goofy McLemore, even during his most sexist moments. Deep Space does not respect women, which isn’t too much of a surprise when you consider that cult B-movie purveyor Olen Ren also brought us the less-than-respectable Hollywood Chainsaw Hookers, a movie whose title leaves very little to the imagination, but it’s impossible to get offended given the movie’s playful, self-aware nature and outright silliness.

I’m basing my sexist observations almost entirely on the behaviour of co-star Ann Turkel’s officer Carla Sandbourn, a real-life model who oozes sexuality in her ill-fitting uniform and fails to even load a revolver convincingly. The precinct captain, perhaps slightly jealous considering his greedy eyes, immediately warns Sandbourn to keep clear of his rogue agent, as those who get close to him naturally wind up dead, which explains why McLemore is so nonchalant and cocksure with absolutely no emotional baggage to speak of.

Turkel is eye candy, plain and simple, but at least the movie isn’t lecherous. Unless, like me, you perceive Sandbourn as the lech in the equation. The expository nature of her relationship with McLemore is priceless. In the space of a couple of short scenes that include maybe a dozen lines of dialogue, she goes from admiration to flirtation to full blown nudity faster than a facehugger high on methamphetamine. She gets naked at the dinner table less than a bite into her dinner date, marveling at the hairy Scotch egg hovering over her. After easily succumbing to McLemore’s absurd attempts at sexual bribery, she even jumps into bed with him, one littered with so much random lingerie there are brassieres hanging off our resident stud’s bedside phone receiver. She even jokes about the sex they had, in public, demeaning herself absolutely. She’s only been at the precinct for five seconds. Talk about landing yourself a reputation.

McLemore’s other partner, who quickly fades into the background, is just as jarringly miscast. He doesn’t convince as a cop for one second. Like pretty much every character in the movie, Ron Glass’ detective Jerry Merris is basically an expositional device who regularly outlines 10 minutes of plot with mach speed efficiency. Not only is he incredibly slow-witted and ill-equipped to handle his profession, he doesn’t even look or act the part. In fact, he comes across as plain weird at times. There’s no clear dynamic here, no believable connection between the characters. You couldn’t imagine them sharing a conversation, let alone a six-pack after a particularly tough day on the job. Prince and Chuck Norris would have been a more authentic pairing. They’re the filmic equivalent of 80s pop duo Hall and Oates.

It’s a case of dumb and dumber when it comes to the film’s detective work too. Despite an abundance of evidence that includes a revelatory alien crash site, alien-inhabited cocoons that, along with a bloody pile of teenage limbs, are handled at will without even a pair of rubber gloves, and the eye witness statement of a stereotypical drunken vagrant, the two are dismissive of the idea that anything unusual or extraterrestrial is at play. When McLemore reconsiders and spells out the obvious in no uncertain terms, his partner still doesn’t believe it, which is perhaps why, when he investigates strange sounds coming from the cocoon that he was somehow allowed to take home from the evidence room, he merely kicks it under the kitchen table with a shrug and a swig of beer, turning his attention to the freshly baked cake he’s preparing. Great fictional detectives are generally ahead of their audience in sniffing out clues and theories. It’s what makes them compelling and interesting. Not McLemore and Merris. They’re like a pair of fifth grade slackers without the inquisitive nature.

For long stretches, Deep Space is like a pale imitation of the Lethal Weapon movies minus the razor-sharp humour, endearing characters and irresistible chemistry, but that’s only half the story. When you hear the words ‘Alien rip-off’, you’re not expecting half measures, and despite its dependence on more grounded, budget-friendly genres, Deep Space does not disappoint. There is intentional humour – some of it lands, most of it doesn’t – but the film’s shameless aping of Alien‘s most iconic moments proves funnier than any attempts at scripted comedy. I had so much fun comparing the movie’s shameless appropriation with the real thing. Like a freshly shed alien skin, it lacks the film’s cerebral aspects, skimping on the scientific makeup and just about every filmic element that make Alien and the equally influential Aliens so special, but the superficial, poorly recreated similarities punch a hole in your face xenomorph style. At times it’s laugh out loud funny.

Despite its inability to venture beyond the stars, Deep Space has done its homework. Ripley is notable by her absence, as are the whole crew of the Nostromo, the colonial marines of the Sulaco… well, just about anything that costs money, but there are striking similarities for movie buffs to point and laugh at. For openers, there’s James Booth’s corporate shill and alien protector Dr. Forsyth, the cheapskate answer to Ian Holm’s malfunctioning droid, Ash, or Paul Reiser’s deliciously smarmy Carter Burke.

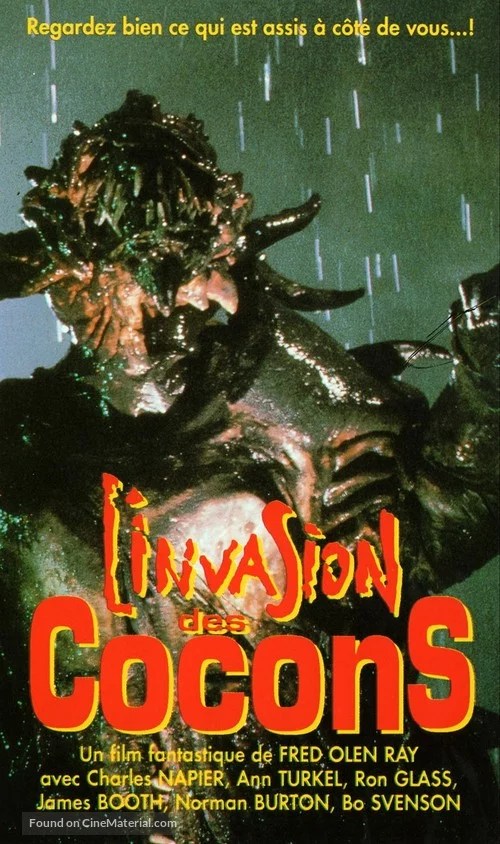

Forsyth is the head of a laughably unconvincing U.S. military satellite program. Following the unpreventable crash of a satellite that happens to contain a new, very familiar biological weapon, Forsyth defies General Randolph’s instructions to destroy the creature, which proves fatal for a very small section of the planet for a very short time. The aliens remain dormant until two teenagers decide to check out the crash site and handle giant cocoons that would surely lead to deadly, unidentifiable disease and painful, prolonged death had the two of them not been mutilated almost immediately thereafter. At this point the alien remains largely in the shadows, a plethora of rubber tentacles and crappy lashings of blood a callback to the red scare monster movies of yore.

At this point I was slightly disheartened, but then Deep Space unleashed its very own facehuggers, which, emerging either from cocoons or chest burster style (at least in one ludicrous instance) are absolutely hilarious. The practical effects team do a pretty good job of recreating Hollywood’s most repugnant arachnids, but the difference in budget is palpable. They’re almost identical in form but, unlike their big-budget counterparts, they look very mechanical, almost like giant, clattering, wind-up toys. They’re easy to dispose of too, doubly so since they’re going up against McLemore and co, who, prior to the movie’s final showdown, lack the clinical nature and assertiveness to handle such a relentless, frenetic parasite. At one point, he manages to yank the creature off a bloodied doctor, only to throw it right in precinct hussy Sandbourn’s face. In that moment, I actually spat out my coffee.

The full-blown xenomorph created for Deep Space is also a sight to behold when finally unleashed. It’s the equivalent of watching The Simpsons on the Tracey Ulman show or buying a knock-off Bart Simpson doll that is inexplicably blue and wearing a dress to avoid copyright infringement. It’s instantly recognizable as a xenomorph, but like the movie something is off. The head is queerly lifeless, the teeth are too plentiful and stick out all over the place like a badly drawn cartoon of squiggly proportions. Not even that iconic flashing light effect or an almost shot-for-shot recreation of the famous ‘it’s behind you’ kill from Alien featuring the terrified cat can lend the film some tension.

The thrill of a relatively action-packed finale featuring giant guns, raging chainsaws and jars of neon gook, that the alien is forced to swallow for some reason, is also negated by one of the most obliquely abrupt endings in B-movie history. This is because our protagonists’ not-so grand exit isn’t quite as epic or as impactful as the director would have hoped. You simply don’t believe they’ve been to hell and back because it’s all so ridiculous. In space, no one can hear you scream, but you can be pretty sure they’ll hear the laughter.

A Very 80s Hero

The ever cocksure McLemore is certainly a man of his time. In an era of cancel culture gone mad, he’d be drawn and quartered for his exploits, especially after bribing his brand new colleague into bed with a bagpipe performance, dressed in full kilt regalia (he’s Scottish apparently).

It’s not what you think either. He isn’t serenading her. He’s trying to annoy her, an annoyance that will only cease if she strips off naked. Which she does. Far too willingly.

But what’s more sexist, the fact that Sandbourn submits so readily to McLemore’s sweaty charms, or the notion that women who dig loose sex as much as men are somehow immoral? Perhaps they were both ahead of their time.

Get Away From Her, You Bitch!

With Armat M41A Pulse Rifles being hard to come by in Olen Rey’s micro-budget monster movie, other weapons are required to combat the fearsome space aliens wreaking havoc in McLemore’s suburbs. Perhaps a powerhouse 44 Magnum in the Dirty Harry mould? Maybe even a spare hand grenade swiped from evidence given the extreme circumstances?

Hard ass McLemore goes with a baseball bat instead, coming to the rescue of a scantily-clad blonde with heaving breasts who is helplessly under attack from an imitation facehugger, one that the detective locates after it accidentally knocks some of her sexy lingerie onto his head.

It proves to be a good choice though. A solitary swing sends the creature crashing through a first-floor window. Which is enough to kill it.

Maybe the situation isn’t so serious after all.

Exposition Impossible

We’ve already established that officer Carla Sandbourn isn’t shy about getting what she wants. She’s also pretty nifty at fleshing out backstory, as her initial courtship proves. Here’s an excerpt:

Sandbourn: You’re a strange one. Everybody’s talking about you.

McLemore: Oh yeah, what are they saying?

Sandbourn: Oh, just that you’re tough and gutsy and very, very good.

McLemore: Oh, wow.

Sandbourn: The special unit says you’ve been in a dozen gun battles and haven’t even been wounded.

And people wonder why he has such an ego.

The Main… Of Course!

After landing a dinner date with the lascivious officer Sandbourn, McLemore sets about preparing his ‘speciality’ meal, but things don’t go to plan when a psychic calls and distracts him from his task, proving her powers by foretelling the gross overcooking of his steaks over the telephone.

Bear in mind, these are the same burnt to a crisp steaks that were raw and freshly seasoned only 30 seconds earlier.

Choice Dialogue

Having just witnessed a blazing ball of fire hurtling towards Earth, a teenage girl is understandably cautious when her boyfriend suggests that the two of them investigate:

Teenage Girl: “Are you crazy? I don’t want to get raped by a Martian!”

Despite its lack of celestial adventure,

Edison Smithis an Alien rip-off to cherish. Instead of fascinating creatures and hyper-tense thrills, we get lazy stereotypes, cheap knock-offs and absurd action, all of it delivered with a perfunctory, paint-by-numbers efficiency that puts it in another universe. And that’s what makes it so great. It’s like a comedic exercise in debasing something brilliant, while somehow becoming brilliant as a consequence.