A young Vincent Price gives a very different horror portrayal in Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s complex period drama

Joseph L. Mankiewicz didn’t want to direct Dragonwyck. For many years in Hollywood, he had lived in the shadow of his older brother, Herman J. Mankiewicz, the screenwriter for the (in)famous Citizen Kane. Dragonwyck was, in essence to the studio system, a woman’s picture, which were, and still are in some circles, looked down upon for supposedly only appealing to the fairer sex. Not only did Mankiewicz direct the film, he wrote the screenplay based on Anya Seton’s 1944 novel, and along with cinematographer Arthur C. Miller, editor Dorothy Spencer and composer Alfred Newman, he created a film that is appealing in every way.

Dragonwyck tells the story of Miranda Wells (Gene Tierney), a naïve, imaginative farm girl who has grown up in a puritanical household led by her father (Walter Huston), a man who believes in American individualism and Christian tradition. He is, unsurprisingly, against the idea of Miranda going to visit her very, very distant cousin, Nicholas van Ryn (Vincent Price), a wealthy landowner or patroon, on the Hudson River. There the long standing system of tribute and tenant farming has existed since Dutch landowners established the system over two hundred years before. Miranda finds herself swept up in a world of aristocratic blood, snobbery, outmoded social and economic mores, madness and murder.

Some dreams are very real I guess. So real they get confused with reality. And then when you wake up, and look around, you find yourself saying, “what am I doing here? How did I get here? What is this to do with what I am and what I want?”

Miranda Van Ryn

By the time Dragonwyck was made, Gene Tierney had starred in the two films that would become the bedrock of her legacy, the Otto Preminger directed film noir Laura (1944) and psychological thriller, colour film noir Leave Her To Heaven (1945). In those two movies, she showed her range, from playing an object of obsession and desire for Dana Andrews and Clifton Webb in the former, to a selfish, destructive femme fatale in the latter. Due to her star power, Dragonwyck should’ve easily been Tierney’s film. But it isn’t. She gives a very good performance, showing a subtle and nuanced maturation from an inexperienced child (who loves to say golly Moses) to a world-weary woman.

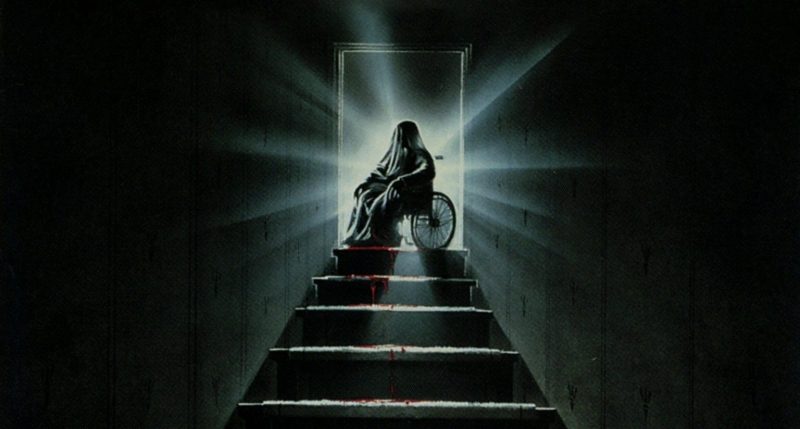

But this is Vincent Price’s film from the moment he appears onscreen to his dramatic death scene, during which he becomes utterly deranged and hallucinates that he is still the patroon of old, before his infant son had died and the Anti-Rent Wars. In hindsight, this film is a crossroads for Price, the point at which his career could possibly have gone in a different direction to which it eventually went. In Dragonwyck he plays a Byronic hero driven insane, and he could’ve become that kind of horror icon, instead of the king of schlock-inclined fare that we know and love him for.

Initially, Gregory Peck had been cast as Nicholas van Ryn, but he dropped out when Ernst Lubitsch became ill and could not continue with directorial duties. I think that whilst Gregory Peck would have given an acceptable performance, he would not have been capable of the cold imperiousness shifting into increasing paranoia and insanity that Price conveys so well. Glenn Langan, whilst handsome and acceptable in the role of the kind doctor defending Miranda from psychological abuse, is utterly milk-toast opposite Price and cannot hope to compare in their scenes together. Even the film knows that Price is its gothic fulcrum, because the tone before and after his appearance shifts noticeably.

The film begins with Tierney frolicking through the meadows on her way to her parents’ humble homestead, sunshine and light music playing. But once the story shifts to the van Ryn estate along the Hudson, the score grows heavier and more brooding. Darkness and rain dominate whilst van Ryn gazes out of storm-lit windows and contemplates how to murder the wife who has borne him a lowly daughter, so that he may be free and clear to marry Miranda.

Dragonwyck explores some very complex themes, the most obvious of which being the social class that existed in pre-Civil War American society. Miranda’s father proudly declares that he does not believe in the aristocratic patroon system, that he would rather own barren rock than farm the richest land if it meant he didn’t own it himself free and clear. Miranda repeats these words when she is treated condescendingly at a ball held at the van Ryn’s mansion, where all the hoi polloi of the patroon families are in attendance. Their snobbery and classism is even more pronounced after Miranda and Nicholas are married, and no one will attend the ball that is to be held due to Nicholas marrying a “lowly” farmer’s daughter. Nicholas shows his own discriminatory inclinations when he describes Miranda’s maid and companion, Peggy (Jessica Tandy) as an unsightly little cripple. It is both ironic and fitting that Nicholas himself becomes “unsightly” as a drug addict who will not leaves the dark confines of the mansion’s attic.

I believe in myself, and I am answerable to myself! I will not live according to printed mottos like the directions on a medicine bottle!

Nicholas Van Ryn

Dragonwyck walks a fine, interesting line between gothic horror/romance and psychological thriller. The supernatural elements of the plot are insinuated, leaving it up to the audience to infer whether or not they are genuine or the product of hereditary madness. It is suggested that there is a curse upon the house and family since the death of Azilde, a great beauty who was brought to the estate many years before by Nicholas’ great grandfather as his young bride. He neglected her and she missed her home in the South. Nicholas and his young daughter, Katrine, supposedly hear Azilde’s ghost hauntingly play the harpsichord at night, but Miranda cannot hear it because she is not a van Ryn by blood. When Nicholas’ status as patroon is no more and he has no hopes of having a male heir, he hears the harpsichord once more. Is this due to his fevered mind and growing madness? Or has Azilde accomplished her deathbed curse of destroying the cold van Ryns?

So much of Dragonwyck is about atmosphere and inference. When Nicholas’ first wife dies, he brings his prized Oleander to her room, and it is later revealed that she was poisoned with one of the plant’s leaves. Later, Nicholas puts the plant in Miranda’s room, which becomes a symbol of doom for Nicholas’ Bluebeard inclinations. The death of Miranda and Nicholas’ son is also perhaps a symbol of the van Ryn’s inbred family line, and perhaps divine punishment for him committing uxoricide. Even Nicholas’ demise is heavy on symbolism. He dies in the throne-like chair upon which he once sat to collect “tribute” from his tenant farmers, his final words echoing the superior opinion he has of himself and his supposed status in society.

The final five minutes of the film suggest a happy ending. It is implied that Miranda will marry the young country doctor who supposedly saved her from her husband’s abuse, although Miranda really saves herself with the help of Peggy. But these five minutes and some chipper Newman score cues cannot erase the darkness of the past 90 minutes. Miranda will live the rest of her life in the shadow of the disaster of her first marriage, and will have her own mournful harpsichord in the form of her husband’s final death stare.

Director: Joseph L. Mankiewicz

Screenplay: Joseph L. Mankiewicz

Cinematography: Arthur C. Miller

Music: Alfred Newman

Editing: Dorothy Spencer

It is also interesting how this story (both film and novel) compare to Jane Eyre. In this version of the traditional gothic, it’s the man who ends up insane in the attic and not the first wife.

LikeLike