Freddy grows paternal in the oddest A Nightmare On Elm Street instalment to date

1984’s Fred Krueger was a truly wicked creation. Emerging from the bowels of a filthy boiler room with a disturbing past that transcended the limits of popcorn horror, Robert Englund’s frazzled child killer and implied pedophile revitalized the moribund slasher thanks to a supernatural twist that would become standard fare in an era of reality-based horror censorship. Just like John Carpenter’s masterwork and blueprint for the soon to be established ‘slasher’, Halloween, Wes Craven’s commercial eureka, A Nightmare on Elm Street, would spawn a whole host of imitators, his dreamworld concept an untapped vein that would run in rivers until the inevitable drought.

Carpenter would openly lament the Halloween series going forward, particularly having been tempted back, against his best judgment, for Halloween II, a movie that upped the gore in an attempt to keep pace with those imitators who would quickly reduce the slasher to self-parody. Craven, too, saw A Nightmare on Elm Street as a standalone movie with a definitive ending, but feeling that he owed a debt to New Line Cinema honcho Robert Shaye, who had taken a chance on a screenplay that had been passed upon with almost universal ambivalence, Craven reluctantly compromised and agreed to a tacked-on ending that left the movie open to a sequel, and ultimately a money-spinning franchise, one that transformed the struggling indie studio into a major Hollywood player. So central to Shaye’s fortunes was the series that New Line was later dubbed ‘the house that Freddy built’.

Despite how fresh, urgent and innovative the original A Nightmare on Elm Street felt upon its release, the movie will never be revered at the level of Halloween or The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Perhaps it didn’t feel as vital or as ahead of its time, but when you consider the ingenuity of the concept, Craven’s deft delineations of dreams and reality, the movie’s comparatively well-rounded cast, including the incredible star turn of Robert Englund as horror’s cackling gunslinger, one of the most befitting musical scores in all of horror, and a series of astonishing practical effects that belied the film’s humble budget, you have to wonder what would have been had Craven been given complete creative control. Without that silly, sequel-setting finale, perhaps A Nightmare on Elm Street would be spoken of in the same bracket, even without the less-is-more formula that preserved its peers more successfully from the inevitability of becoming visually dated. Despite those imperfections, it is still one of my favourite horror movies of any era.

On the flipside, would we still be talking about Fred Krueger all these years later had it not been for the plethora of sequels that Shaye’s savvy commercial aspirations spawned during the 1980s and early 1990s? Thanks to 2010’s lazy and uninspired reboot and an ageing Robert Englund’s inextricable synonymity with the character, Krueger has been off the radar for the longest time along with fellow slasher icon Jason Voorhees (the latter due to long-running legal disputes), while Halloween and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre are alive and well, both franchises finding audiences as recently as 2022. Michael Myers is currently the undisputed box office champ, his recent run of outings raking in half a billion dollars in under five years, but while the Halloween franchise wallowed in the doldrums in the late 80s following a 6-year hiatus (7 if we discount a Myers-less Season of the Witch), Krueger was the commercial king – at least for a short time.

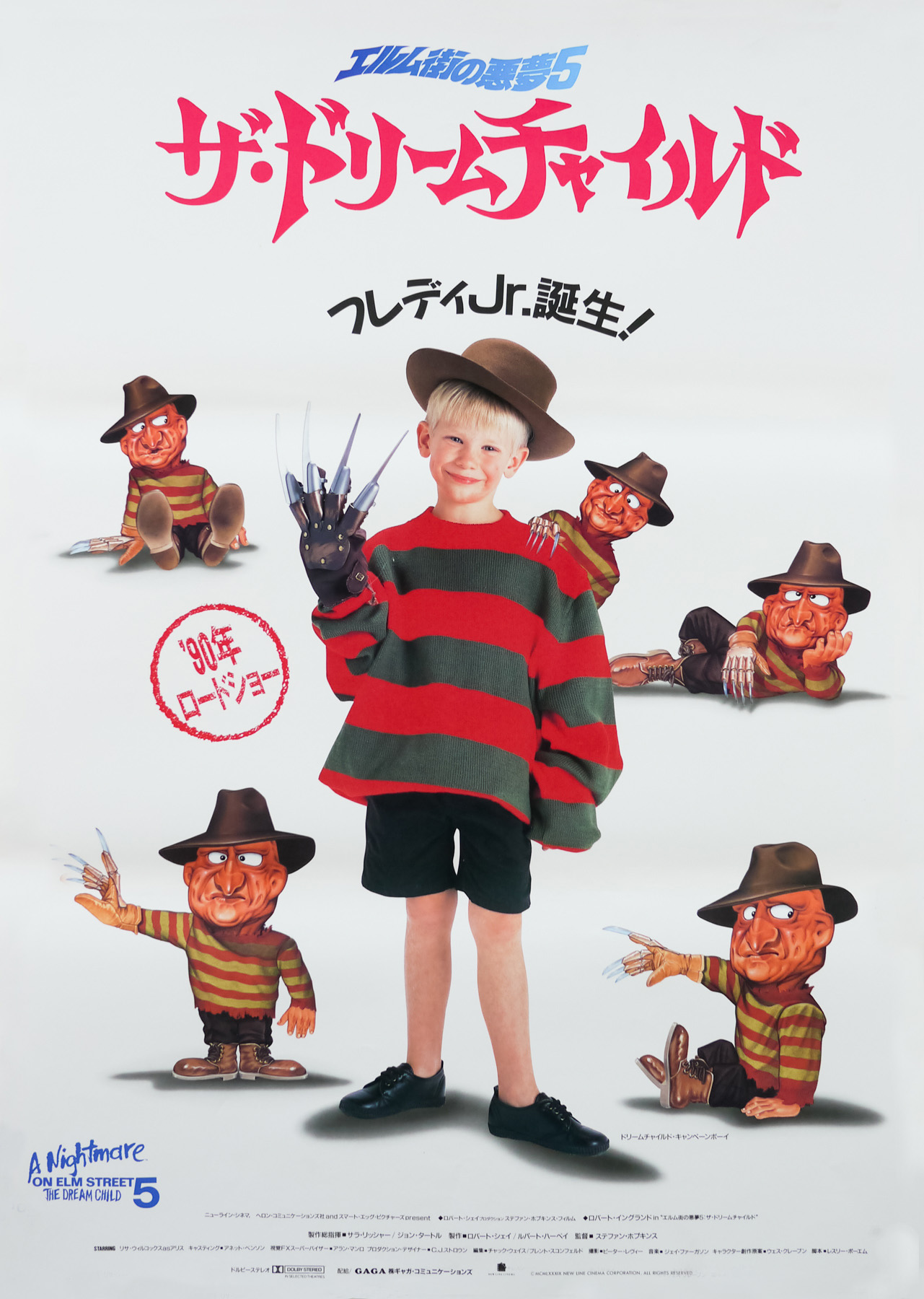

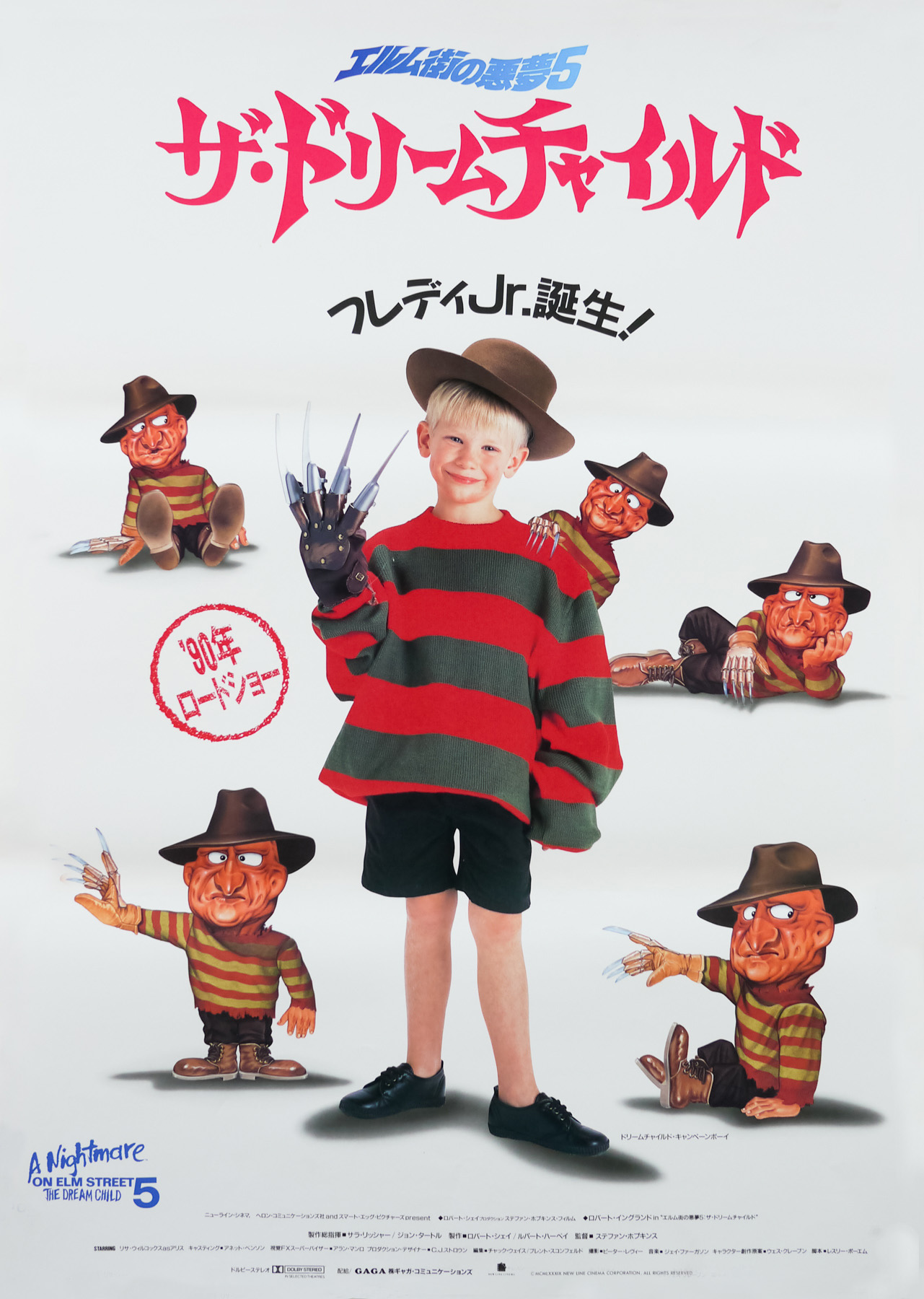

It’s a boy!

Fred Krueger

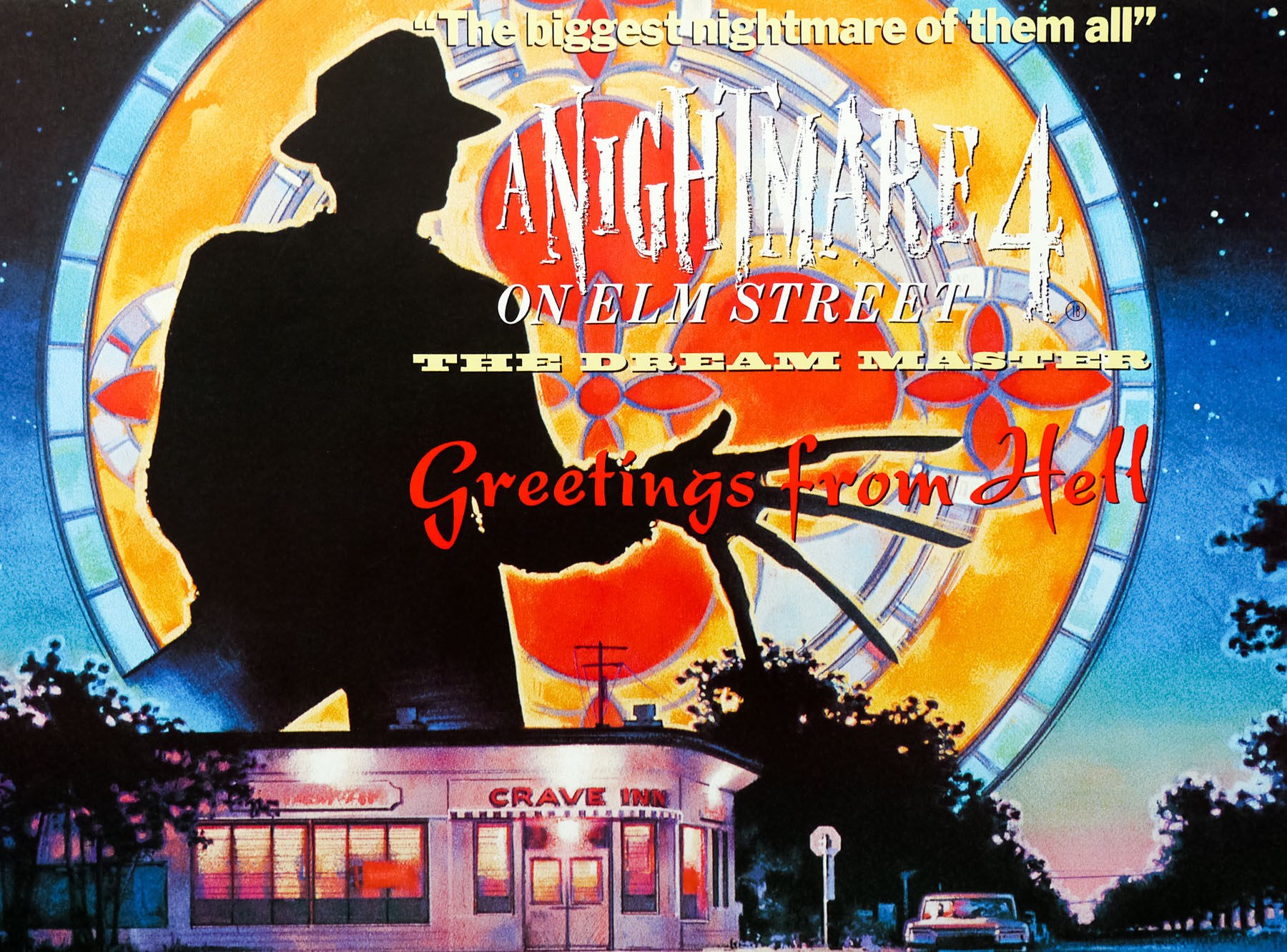

While Carpenter’s original Halloween formula was run into the ground by an abundance of sleazy, Sean Cunningham style clones, the A Nightmare on Elm Street series only had itself to blame, Shea and a plethora of writers and directors jumping the shark like Fonzie on a crystal meth infused cash grab following 1988’s A Nightmare on Elm Street 4: The Dream Master, a movie that, while posting the best box office returns up to that point, embraced commercial avenues that all but killed the series creatively (for those who don’t know, the term ‘jumping the shark’, defined as ‘a television series or film that reaches a point when far-fetched events are included merely for the sake of novelty, and are indicative of a decline in quality’, was coined in 1985 by radio personality Jon Hein in response to a 1977 episode from the fifth season of the American sitcom Happy Days, in which the character of Fonzie (Henry Winkler) jumps over a live shark while on water-skis).

Whatever audiences think about a mostly sub-par franchise, the A Nightmare on Elm Street series has always been a unique beast. While something of a commercial success owing to the popularity of the original, Jack Sholder’s controversial sequel A Nightmare on Elm Street Part 2: Freddy’s Revenge almost put the series on the shelf as early as 1985. Later ousted as a ‘gay panic’ movie, Freddy’s Revenge got many things right, not least the casting of ‘final boy’ Mark Patton, the film’s gay subtext in a homophobic, AIDS-scare environment the perfect recipe for Krueger, a character who feeds on fear and isolation. It also got a lot wrong in the eyes of many, the movie neglecting to explore Craven’s original dreamworld concept in any great detail, becoming more of a straight-up possession movie. As A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: The Dream Warriors director Chuck Russell would say, “The studio rightfully felt that Nightmare 2 was a bit of a misfire… At that point, they were uncertain [the series] would continue. I thought in Nightmare 2 Freddy became almost less personable… more of a typical slasher than a dream demon.”

Ironically, The Dream Warriors would trigger Krueger’s descent into the realms of mystique-crushing caricature, the line “Welcome to prime time bitch”, famously ad-libbed by Englund as he grew further into the role, a precursor to the overbearing celebrity that would drain the series of any semblance of genuine horror. Fully embracing and expanding upon Craven’s dreamworld vision, Russel’s threequel, which remains the favourite instalment of many fans, focused on the kind of lavish practical effects that became the sole selling point of future instalments. Though the movie trod a fine line between horror and self-aware comedy, occasionally overstepping the mark with its pantomime antics and cute one-liners, it was a mostly winning formula that rescued the series out from the cold in emphatic style. It also secured the chances of yet another sequel as Freddy fandom reached fever pitch.

While A Nightmare On Elm Street 4: The Dream Master proved to be the most financially successful instalment yet, securing New Line Cinema’s future and then some and catapulting Freddy and Robert Englund to a new celebrity stratosphere, Die Hard 2 director Renny Harlin’s sequel started a creative rot from which there was no coming back. Wes Craven’s New Nightmare, a comparatively low-key, conceptual forerunner to the more commercially viable Scream, would go some way to restoring Krueger’s credibility as a genuine horror icon, but Harlin’s hyper self-aware assault, which set out to make Krueger an action hero, left future writers and directors picking up the pieces like razor-gloved architects sifting through the creative rubble. With nods to Jaws, a paper-thin cast that immediately undid the mostly stellar work of The Dream Warriors, and a ceaseless array of one-liners that left the likes of Schwarzenegger shrinking in the shadows, the film’s one saving grace was its practical effects set-pieces. Legendary SFX artist Screaming Mad George worked wonders on occasion, but a poorly handled budget meant that some set-pieces were ditched entirely, others replaced with lame scenes like Rick’s karate showdown with an invisible Freddy. If that wasn’t enough to offend traditional horror fans, The Dream Master even buried an absurd Krueger rap in the end credits, his descent into pop culture farce complete.

Robert Englund would cite the fourth instalment as his favourite – unsurprising given his larger than life performance and massive celebrity status in 1988 – but despite the movie holding a massive degree of nostalgic power for 80s kids who were caught up in the sheer madness of the character’s popularity, which even extended to children’s toy lines that irked religious groups with their dark, amoral sense of irony, it’s pretty shallow and ineffective in hindsight. For all of its many flaws, and despite writers strikes that to some extent effected a movie that was often scripted on the fly, at least Harlin had a sense of purpose in regards to Krueger. On his handling of the franchise, he would later explain: “It’s hard to scare [the audience] with, you know, a surprise: Freddy comes around the corner. Wow! I felt that we had to make him the hero. He is like the good guy of the story ― in a way though, he’s the bad guy ― but he is kind of like the person we root for. He is Rambo. He is James Bond. And why I use James Bond as an example is, he was not only heroic but he was like… really cool. He’s like the guy who has the Martini and the cigarettes and the women. I wanted [Freddy] to be like the coolest guy there is.”

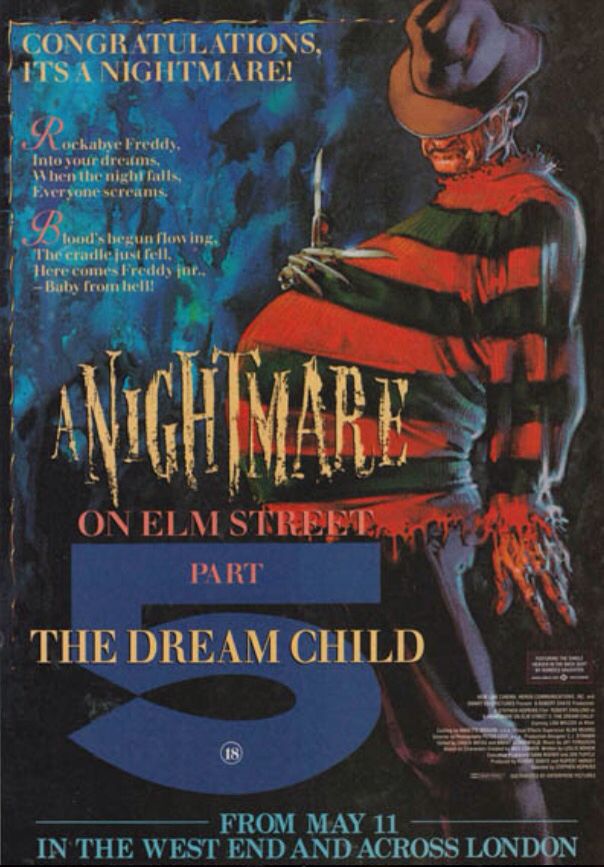

The same does not apply to 1989’s A Nightmare On Elm Street 5: The Dream Child, which arguably did more damage to the franchise than an other instalment; even 1991’s Freddy’s Dead: The Final Nightmare, a film whose lack of budget, further descent into celebrity self-parody, and gimmicky 3-D finale sealed the deal for the franchise’s original run. The movie is so far detached from Craven’s original, so steeped in self-parody and mired in ludicrous attempts at establishing unnecessary mythology, a trend that would continue in the instalment’s successor, that you’re left scratching your head for the most part, wondering who on Earth this movie is for. There’s still an overriding sense of peewee product marketing, of flogging a dying horse to gullible kids the world over, but jarring moments of sexually-orientated darkness rest awkwardly as a consequence. This movie was considered a creative disaster almost four decades ago, but today it is almost unwatchable save for the perverse intrigue of witnessing a franchise implode in the most perplexingly off-key manner.

It’s well known that, much like its predecessor, The Dream Child‘s script, unfinished as New Line neared production, was part-written and tinkered with on the fly. The film’s basic storyline, first pitched back in 1986 for the third instalment, was the product of three different writers, leading the Writers Guild of America to intervene when it came to the movie’s credits. The MPAA also made life hard, demanding significant cuts that resulted in arguably the least violent entry in the series. Cast and crew members were disappointed with the theatrical cut of the movie, citing a lack of violence in what was supposed to be a horror movie. Given Krueger’s upspoken but transparently obvious demographic, namely tweens and teenagers, the MPAA’s concerns are understandable, but the film’s sexual references remain up in bright lights. It’s such a mess.

The movie wastes no time embracing its icky intentions. A Krueger-less dream sequence starring Robert Englund out of makeup, presumably as Freddy’s father, reminds audiences of the character’s origins. Freddy, dubbed the bastard son of 100 maniacs in The Dream Warriors, was born after mother Amanda Krueger was accidentally locked in an insane asylum, where she was subsequently raped by 100 men, leading to the future monster’s not-so-immaculate conception. Soon he will be reborn into the subconscious of returning former foe Alice (Lisa Wilcox), and, if his nefarious and wildly elaborate plan plays out the way he intends, back into the real world to wreak havoc all over again. It’s another tenuous set-up for a series of rinse and repeat dream sequences that our latest batch of kids are somehow unprepared for, even with two former victims in their midst, who themselves seem awfully glib when echoes of ‘ol pizza face begin to reverberate on the fringes of a high school graduation.

Thanks to Renny Harlin’s previous overindulgences, buying into the whole Freddy concept a fifth time is nigh-on impossible. The paper-thin characters, increasingly elaborate set-pieces, and wisecracking anti-heroics already a stale formula that has been stretched as far as possible. The skipping children, that infamous nursery rhyme, the screeching scrape of Krueger’s finger knives have evolved from novel and creepy to pleasingly familiar to overbearingly stale. By this point, ‘bitch’ is less a clever pun, more a lazy catchphrase repeated ad nauseum for the sake of it. At times it feels like a sitcom ghosting its way through a final season, all past glories and absurd plot developments that betray the essence of what originally made that show great. Krueger’s first words, after evolving from a wretched looking newborn into a fully grown monster, confirm our worst fears before we’ve even got going. “It’s a boy!” Strap yourself in folks, there’s a long, perplexing ride ahead, though morbid curiosity will no doubt keep you watching until the very end.

The same criticisms can be levelled at the movie’s dream sequences. There are a couple of impressive practical effects set-pieces, but it feels like the best is already behind us, the novelty diluted to a thin gruel. There are no clever, Craven-esque dream delineations. There is no uncertainty, no blurred margins between dreams and reality. Instead we’re greeted with abrupt and obvious signifiers, the skipping children, the Freddy nursery rhyme, or big, almost operatic set design with a gothic flavour, footage inserted by Hopkins after the fact. It was visually impressive for the time, but more fantasy than horror. It’s like Freddy has wandered onto a reject set for Batman Returns, evil baby strollers wandering the hallways of Alice’s subconscious as the film’s ludicrous plot takes shape. Hopkins is a stylish, effective director, but the script and basic concept don’t give him or anyone else a chance, including Wilcox and Englund, who both deserve better.

The Dream Child‘s basic premise is hard to stomach. If religious groups were worried about the prospect of Freddy Kruger dolls and emblazoned pajamas, then a movie that sees a demonic rapist and serial child killer entering the mind of a high school graduate’s unborn child with the aim of returning to the real world would have been enough to send them to an early grave. It’s hardly offensive given the movie’s otherwise tepid nature, but it’s bizarre nonetheless, as bad a case of sequelitis as you’re likely to witness. Alice spends much of the movie in dreamworld dialogue with her future child, Jacob, whose nightmares from the womb offer her some insight into Krueger’s nefarious, long-winded plans. This leads to some rather brilliant practical effects inside Alice’s womb that make absolutely no sense until a blunt and absolutely necessary bout of exposition on our protagonist’s part informs us that Krueger is somehow trying to pollute her unborn child with the souls of her fallen comrades so he’ll grow up to be just like him. If Alice survives this whole ordeal, she may consider a career as a super sleuth detective, or, even better, a psychic medium.

Alice, who retains the ability to enter her friend’s dreams, or at least abstractly witness them as they’re happening, watches as they succumb to Krueger’s twisted ironies in a fashion that is far less inspired than previous entries. Krueger, who true to his nature orchestrates his kills in a way that makes them seem like accidents, is a pale shadow of his former self. You can’t fault Englund, who throws himself into the role like never before, but his strength was always his ability to add a touch of dark humour to horrific events. Here, he’s a one-man band of inane wisecracks that flood the film’s running time like endless guitar solos on an overproduced cocaine album.

Even the most impressive set-pieces, like a returning Dan’s nitro-induced, body horror bike death, are ruined as the movie’s child-slaying prankster indulges in endless pantomime shenanigans, even tearing his own arm off to use as a seatbelt at one point. Krueger is no longer frightening, he’s a walking stand-up act, who, even when force-feeding bulimic victim Greta, fails to convey the dark manipulation that made his victims, and as a consequence the audience, feel so helpless and isolated. Put succinctly, Krueger is no longer the all-too effective monster who struck fear in the hearts of a generation. He doesn’t linger in the shadows, tease the subconscious, or delight in the slowly delivered wickedness, he’s front and centre, rolled out in stocks for the custard pies, with make-up design that is more fun than fearsome, the result of an aesthetic that was designed to cut down on make-up application. There’s absolutely nothing to fear beyond a plethora of cheap wisecracks, vaudevillian theatrics and an endless supply of mock costumes, not least the infamous Super Freddy, the personification of all that is wrong with a post-Dream Master Krueger.

Do unborn babies dream?

Alice Johnson

Aspiring comic artist Mark, a lovelorn nerd who buys into the whole phantom killer concept based on his obsession with fallen beauty Greta, wanders into a beautifully constructed A-ha video, only to come up against a beefed-up Krueger caped in superhero lore. The whole scene is a perfect example of how much the series had lost its way based on commercial intentions that, while securing the future of New Line, all-but destroyed the reputation of the monster who made them. The sequence is clearly aimed at kids, a precursor to the planned comic book series that never was. When you market an R-rated horror franchise so transparently at children you get a hodgepodge of violence, the inappropriately sexual, and tepid, cartoonish ideas that are completely at odds with each other. Make no mistake about it, tonally, this movie is all over the place. It’s gobsmackingly dissonant at times.

With a disappointing gross of approximately $22,000,000, The Dream Child was the poorest performing box office entry of the series up to that point, an indication of how far the Krueger character had been rammed down audiences’ throats in such a small space of time. Even Freddy’s Dead significantly outperformed it, owing to the draw of the sixth instalment indeed being the final nightmare, a ruse that worked for the Friday the 13th series back in 1984 when Friday the 13th Part IV: The Final Chapter falsely advertised Jason’s demise for a boost in returns, only to bring the series back with an impostor killer. Craven would salvage his exploited character with underappreciated meta innovator New Nightmare, but coming only four years after Freddy’s Dead, Freddy fatigue lingered long and hard, the movie tragically posting worse numbers than The Dream Child. Only years later would the film find an audience and the appreciation it deserved.

I’m sure plenty appreciate The Dream Child for what it is, and that’s totally fine, but I’ve always preferred my Krueger on the darker side, which in hindsight was a very brief period indeed. Even as a kid and bona fide Freddy fanatic, this movie disappointed me to the extent that I went into Freddy’s Dead with very low expectations. 35 years later and very little has changed. There’s some impressive imagery on display, an absolutely potty practical effects finale delivering on audience expectation amid the unrestrained madness, but the negatives far outweigh the positives. It may not have ignited its capitulation, but The Dream Child‘s tonal ambiguity and lack of conviction proved the death knell for the series as horror’s main course. Freddy’s Dead was merely the regretful second helping.

Director: Stephen Hopkins

Screenplay: Leslie Bohem

Cinematography: Peter Levy

Music: Jay Ferguson

Editing: Brent A. Schoenfeld &

Chuck Weiss

Although I also really enjoyed Dream Warriors, it was the start of a slippery slope creatively for the franchise, and Dream Child was the unfortunate culmination of that sharp decline. The Nightmare on Elm St franchise is a curious one really, hugely successful in so many ways, yet architect of its own demise in others. NOES Part 5 Dream Child has a few standout moments, but very little to recommend it really, and it’s kinda sad now looking back at how this iconic horror franchise became its own worst nightmare.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Indeed. Totally agree. By the time Freddy’s Dead limped into existence, the series was finished. Loved New Nightmare but the damage had been done, nobody cared. It did become its own worst nightmare. Damn! Should have ended the article with that line. 😁

LikeLiked by 1 person

SUPER FREDDY!

LikeLike

oh, sorry, didn’t mean to type SUPER FREDDY! four times in a row

i’m just very passionate about him!

LikeLike

I can see 😁

LikeLike