A New Age Bond, Blockbuster Action Sequels & the Death of Paramount-era Jason… VHS Revival Brings You All the Retro Movie News From July 1989

July 5

The summer of ’89 was both a fond farewell and a long-awaited goodbye to the decade of decadence, dynamic action blockbusters and influential rom-coms reminding us just how great the 80s were in cinematic terms. The rise of the numbered sequel, while viewed as part of a wider trend of creative stagnation by past generations, would remain a staple going forward, and in July 89′ it delivered one of the greatest ever produced. It would also deliver one of the poorest ever produced, the 80s horror boom finally feeling the strain of oversaturation in an era of bloodless censorship.

July 5 was also a reminder of the dreary lows of 80s Hollywood with one-note comedy Weekend at Bernie’s. Starring ‘Brat Packer’ Andrew McCarthy and bad movie magnet Jonathan Silverman as two struggling execs looking to get a leg-up on the corporate ladder, the movie takes place at the summer home of boss Bernie (Friday the 13th Part VII: The New Blood‘s Terry Kiser), who plans to have the desperate duo killed after they stumble upon some fraudulent business activity, which they believe will land them in his good books. Problem is, Bernie is the thief in question, and after they arrive to find his still warm corpse, the two are forced into a grotesque charade that attracts the attention of the same hitman who whacked old Bernie in the first place.

Not the worst set-up, but the delivery is painful to say the least. First Blood director Ted Kotcheff fails to prop up an already moribund script that focuses on black, sometimes perversely sexual gags that crash-land like a Boeing 747, and prove about as funny as lost bags at a tropical airport with faulty air conditioning. The movie drips with bad taste in its attempts to tackle a comedic idea that has always proven problematic. Put succinctly, dead bodies and comedy don’t mix, particularly in such a claustrophobic, drawn-out manner that makes complete idiots out of the entire cast (during one scene, Bernie’s mistress even attempts to instigate sex while remaining none the wiser). The movie is charmless, wearisome and incredibly dumb. Another John Hughes alumni, Jon Cryer, was originally considered for McCarthy’s role. He viewed it as a bullet dodged, I’m sure.

On the subject of sequels, against all odds, Weekend at Bernie‘s managed a belated one. 1993’s Weekend at Bernie’s II would move the action to the US Virgin Islands in search of Bernie’s embezzled riches, proving beyond a shadow of a doubt that there is no geographical solution to a creative problem, though you do have to appreciate the delicious irony of the movie’s tagline: Bernie’s Back… And He’s Still Dead. We could have told you that the first time around. The reason for the sequel, which failed to break even, was the original movie’s fairly healthy box office returns, Weekend at Bernie‘s managing $30,000,000 on a budget of approximately $15,000,000. Fool me once, shame on you, but you ain’t fooling me twice.

July 7

The summer got underway in style on July 7 with Richard Donner’s high-octane action sequel Lethal Weapon 2, which many believe to be superior to 1987’s alternative yuletide thriller Lethal Weapon. The original Lethal Weapon was a dynamic, buddy cop action classic which introduced audiences to arguably the genre’s most lovable pairing in Mel Gibson’s widowed Vietnam vet with a death wish, Martin Riggs, and “too old for this shit” family man and supposed retiree, Roger Murtaugh (Danny Glover). Against a backdrop of modern-day loneliness, loss and festive reconciliation, the movie forged a reluctant friendship that would only blossom as the series unfolded.

Originally scripted as a much darker outing titled ‘Play Dirty’, Donner described his vision for Lethal Weapon 2 as an action piece of a continuing saga in (the characters’) lives, the movie placing a bigger emphasis on comedy by introducing Joe Pesci’s lovable conman Leo Getz as the third Stooge, adding an extra element of dynamism to our already flourishing duo. Despite Riggs being more of a domesticated animal by this point, becoming an extended member of the Murtaugh homestead in a move that took away some of the character’s raw edge, Lethal Weapon 2 is still plenty dark, owing to developments involving Riggs’ deceased wife and new love Rika Van Den Haas (Patsy Kensit), along with two first class villains in the form of cold fish assassin Vorstedt (Derrick O’Connor) and the diplomatically immune Arjen Rudd (Joss Ackland). An alternate ending, shot by Donner, even had Riggs dying, something that critics of those later sequels may have preferred, particularly original Lethal Weapon 2 writer Black, who was ultimately usurped by Jeffrey Boam.

“The problem was that with Lethal Weapon 2 they did a lot of comedy,” Black would tell Empire Magazine. “My draft had one scene with Joe Pesci’s guy. He had a few lines. In their version, they had essentially the same character but throughout the entire script. It’s all about edge to me. This guy who was gradually brought back to life and brought back into the real world, and he can let his guard down and learn to accept the love of real people, and in my version of the sequel that’s the very love for that family that makes him say ‘ok, now I gotta go back and die, basically, to protect them’. And they didn’t like that idea.”

Personally, I’m glad Riggs stuck around. Few action films are as warm, funny and action packed as the Lethal Weapon series, a formula that would continue on into the late 90s. Sure, there was a notable drop-off in quality in Lethal Weapon 3, the series entering action sitcom territory by the unnecessary, if somewhat unfairly maligned Lethal Weapon 4, but there was always the dependable axis of Riggs and Murtaugh to lean on, with an ever-expanding cast of lovable characters who quickly became like family. Despite exhibiting the typical symptoms of sequelistis, those later instalments are still superb action films that have aged surprisingly well.

The great thing about Lethal Weapon 2 and the Lethal Weapon films in general is that Gibson and Glover receive almost equal billing, which speaks to the kind of chemistry that Donner described as “seventh heaven”. Sure, Gibson is the blue-eyed heartthrob and titular lead, but Glover wasn’t your typical black partner riding the coattails of a white saviour, the third and fourth movies placing Roger firmly at the heart of the story. One of the finest scenes of the franchise, Lethal Weapon 2‘s famous bomb on a toilet scene, displays the perfect blend of heart, humour and intense action that became its hallmark. The magic was in the camaraderie. As Donner would recall, “[Gibson and Glover] found innuendos; they found laughter where I never saw it; they found tears where they didn’t exist before; and, most importantly, they found a relationship — all in just one reading.”

Audiences were already spellbound by the time Lethal Weapon 2 hit theatres, the movie becoming the third highest-grossing of 1989 in the US, with a box office of $147,253,986. Third place may not sound too impressive, but bear in mind that they were beaten by two of the cinema’s biggest draws in Tim Burton’s hugely anticipated Batman and Indy sequel Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. Lethal Weapon 2 was also partly to blame for the poor performance of yet another huge franchise returning to the big screen on July 14…

July 14

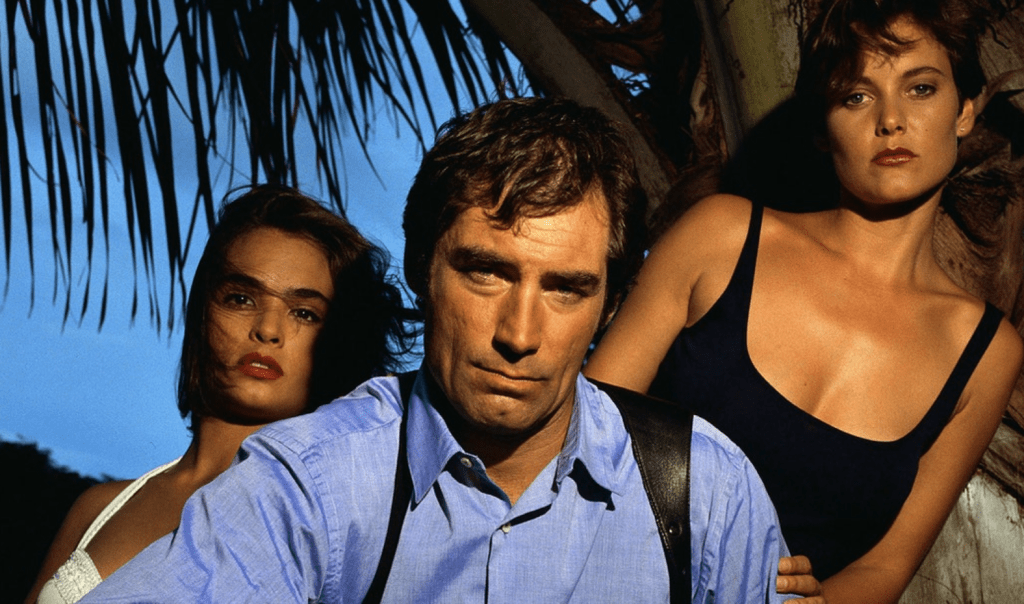

When Timothy Dalton was finally announced as Roger Moore’s successor as the irrepressible James Bond (he had been flirting with the role since way back in 1981 for the suitably cold (For Your Eyes Only), eyebrows were immediately raised. In an era when black and even female actors are being considered as the next 007, it’s crazy to think that many were upset by the fact that Dalton was Welsh. Of course, that was one of many complaints made by fans who had grown accustomed to the eyebrow-raising quips of one Roger Moore, who, a handful of meaner moments notwithstanding, had taken the series firmly into superhero territory. In 1973, when Roger debuted in quasi-blaxploitation effort Live and Let Die, the previous generation had lamented Moore’s relatively wimpish, cosmopolitan demeanour. The Bond you grew up with will always be special. It’s only natural that audiences find it hard to let go.

Pulitzer Prize winning critic Roger Ebert initially agreed that Dalton seemed like an ill fit for the role of Bond. In his two-star review of Dalton’s debut, 1987’s The Living Daylights, Ebert would write, “The raw materials of the James Bond films are so familiar by now that the series can be revived only through an injection of humor. That is, unfortunately, the one area in which the new Bond, Timothy Dalton, seems to be deficient. He’s a strong actor, he holds the screen well, he’s good in the serious scenes, but he never quite seems to understand that it’s all a joke.” After seeing Dalton’s second outing as 007, 1989’s License to Kill, Ebert would have a complete change of heart, writing, “On the basis of this second performance as Bond, Dalton can have the role as long as he enjoys it. He makes an effective Bond – lacking Sean Connery’s grace and humor, and Roger Moore’s suave self-mockery, but with a lean tension and a toughness that is possibly more contemporary.”

Unfortunately, US audiences had already made up their minds. Though the film would gross (a reasonable by Bond standards) $156,167,015 worldwide, it would only manage $34,667,015 in the US and Canada, and while Dalton was set to return for a third Bond instalment, a four-year legal battle involving the rights to the franchise delayed production beyond the actor’s contract. In an era of high-octane action and dynamic, cutting edge movies such as Lethal Weapon and Die Hard, the same old Bond formula was beginning to feel just a little stale by the latter part of the decade. In the US, especially, there was a feeling that Bond had in many ways been left behind.

This is ironic since License to Kill was very much a high-octane, atypically violent anomaly in the series that still proves hugely divisive among Bond fans, many traditionalists believing that it strays too far from the beloved original formula. Contrarily, others view Dalton’s final outing as a movie that was ahead of its time. In 1989 it seemed that License to Kill was scurrying to keep pace with action movie trendsetters, but it also laid the groundwork for 21st century Bond, which was still many ludicrous Pierce Brosnan instalments away. The film’s violent modernisation also contributed to its disappointing box office, the movie lumbered with a PG-13 rating in the states and an 18 certificate in the UK, cutting out a huge chunk of Bond’s typically broad demographic.

License to Kill‘s plot is also an unusually dark one. Taking influence from Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo, the film sees Bond go rogue and embark on a personal revenge mission following the torture and murder of a fellow agent and his wife on their wedding day. It’s a fittingly cold premise for the world of international espionage after almost two decades of cartoon hijinks, but perhaps one that audiences were not quite ready for. Dalton is utterly compelling as he infiltrates the operations of drug lord and General Manuel Noriega clone Franz Sanchez, played by an effortlessly devilish Robert Davi, even if the character’s incautious recruitment of Bond is laughably stupid. Cocaine is a powerful drug, I guess. Albert Broccoli’s daughter, Tina, had suggested Davi for the role.

The film also benefits from great female casting in the form of Sanchez’s smitten-with-Bond girlfriend-come-prisoner, Lupe Lamora (a positively smouldering Talisa Soto) and Carey Lowell’s plucky ex-army pilot and DEA informant Pam Bouvier. Arguably the greatest pure actor to don the famous tuxedo, thespian Dalton was unwilling to commit to a long-term Bond contract, even after those pesky legal disputes had been put to rest. Sometimes it’s better to burn out than to fade away.

Rob Reiner continued his incredible 80s run with iconic, best-in-class romcom When Harry Met Sally, also released on July 14. Coming off the back of 1984’s innovative mockumentary This is Spinal Tap, cult teen comedy The Sure Thing (1985), cherished Stephen King adaptation Stand By Me (1986) and 1987’s similarly adored fairy tale adventure The Princess Bride (1987), the film was nominated for an Academy Award for best screenplay. Though he has never been nominated for an Oscar himself, the magic would not end there for Reiner, 1990’s Misery bagging an Academy Award for best actress (Kathy Bates). His next film, 1992’s acclaimed legal drama A Few Good Men, would bag another four Academy Awards nominations, though Clint Eastwood’s superlative western Unforgiven would understandably dominate the gongs.

Starring Billy Crystal and Meg Ryan, When Harry Met Sally revolves around a series of chance meetings over a period of twelve years and explores the idea of plutonic relationships and whether they are possible, a concept inspired by Reiner’s real-life divorce from actress and fellow director Penny Marshall. Harry was in turn inspired by an interview with Reiner conducted by the film’s writer, Nora Ephron, who based Sally on herself and her friends. Crystal would also make contributions to the script. In 2022, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant”.

When Harry Met Sally — arguably the quintessential romcom of the 80s and a massive influence on the genre going forward — is of course best remembered for its racy, simulated orgasm scene, filmed at New York’s world famous Katz Deli, and the oft quoted line of a seemingly prudish bystander, delivered with deadpan brilliance by the late actress and jazz singer Estelle Reiner, which if you haven’t already presumed was the mother of director Rob. Estelle was very much a bit-part actor, with small roles in only five movies, including 1980’s Dom DeLuise-led comedy Fatso and off-the-wall Steve Martin vehicle The Man With Two Brains (1983), but she was forever immortalised by her offspring, the “I’ll have what she’s having” quip ranked 33rd on the American Film Institute’s list of the Top 100 movie quotations, just behind Casablanca‘s “Round up the usual suspects” no less. Quite the legacy for a relative part-timer.

When Harry Met Sally is one of those special films that continues to be embraced generation after generation, thanks in large part to a razor-sharp script, universal themes that transcend eras and the magical chemistry of its lead actors. “It’s actually more important as time goes by because people fall in love every day,” Crystal would tell The Hollywood Reporter. “People fall out of love every day. People find each other, they lose each other every day. And new generations keep finding When Harry Met Sally. We’re forever young in that movie, and we represent them. They relate to us.” When Harry Met Sally was a huge smash for Reiner and Castle Rock Entertainment/Columbia Pictures, raking in a formidable $92,800,000 on a budget of only $16,000,000.

July 21

Released internationally as The Vidiot, “Weird Al” Yankovic vehicle UHF sluiced into theatres almost unnoticed on July 21, a slew of blockbuster hits, including resilient June releases Batman, Ghostbusters II, and Honey, I Shrunk the Kids, and even May’s franchise adventure sequel Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, a universally recognised property that continued to pull in the punters, reducing the film to the shadows of obscurity.

Primarily a musician who achieved international fame with puerile parodies of notable pop songs by artists such as Michael Jackson, Queen and Nirvana, ‘Weird Al’, real name Alfred Matthew Yankovic, peaked in the mid 80s and again briefly in the early 90s with hits ‘Fat’ (based on Jackson’s ‘Bad’), ‘Smells Like Nirvana’, and ‘Amish Paradise’, a parody of Coolio’s ‘Gangster’s Paradise’, itself a loose cover of Stevie Wonder’s ‘Pastime Paradise’ and the marquee hit for ‘white saviour’ classroom drama Dangerous Minds, starring Michelle Pfeiffer. Yankovic would even parody himself in 1994’s Naked Gun 33⅓: The Final Insult, a self-mocking cameo that spoke for itself.

Co-starring future Seinfeld favourite Michael Richards, UHF is a satirical anthology about an indolent dreamer named George Newman (Yankovic), who fortuitously finds himself managing a moribund local TV station, hiring former janitor and friend Stanley Spadowski (Richards) to help him turn around the station’s fortunes, even giving him his own show as part of an off-the-cuff rejig that replaces old re-runs with, you guessed it, a series of self-contained parodies, which run out of steam rather quickly when stretched beyond the star’s typical, 3-minute pop video format, which mostly relied on juvenile wordplay at the expense of others.

Capitalising on his unexpected rise to prominence in the mid 80s, Yankovic’s manager, Jay Levey, who would co-write UHF, pitched the idea of a movie as early as 1985, sketching several parodies before dreaming up a plot to attach them to, aiming to emulate the superb Zucker, Abrahams, Zucker spoof Airplane (1980), and, like pretty much everyone who has attempted to hijack their Police Squad formula, they failed miserably. Caught up in ‘Weird Al’ fever, the now defunct and famously haphazard Orion Pictures agreed to fund the picture, imagining healthy returns for their $5,000,000 outlay.

Alas, reviews for UHF reflected its woeful box office returns, the movie barely breaking even with an estimated gross of $6,100,000. The occasionally scornful Roger Ebert would call the movie “…the dreariest comedy in many a month, a depressing slog through recycled comic formulas,” adding “I did not record a single laugh during the running time of the film, and although I admittedly saw the movie at a press screening and not on a Saturday matinee at the multiplex in the mall, I wonder how many laughs there will be when the movie does go public. It’s routine, predictable, and dumb – real dumb.”

July 28

Despite kicking off its unrelenting 80s run of diminishing sequels with one of the most successful indie movies of its era, the Friday the 13th series, triggered by a glib phone call from series producer Sean Cunningham, during which he told eventual writer Victor Miller, “Halloween’s doing really well at the box office, let’s rip it off”, was never likely to win any critical plaudits, but 1989’s Friday the 13th Part VIII: Jason Takes Manhattan, released on July 28, was, and still is, the very worst of the bunch.

To be fair, the series had its fair share of problems to contend with, mostly relating to the judgemental eye of the MPAA (Motion Picture Association of America), who set out to castrate the franchise almost from the very beginning, but more so following 1984’s dubiously titled Friday the 13th Part IV: The Final Chapter, which coincided with America’s peak obsession with the slasher boom and the moral outrage of critics and parent groups, both of whom successfully petitioned to have Charles Sellier’s infamous yuletide slice and dicer Silent Night, Deadly Night pulled from theatres. Ironically, this benefitted Wes Craven’s vastly superior A Nightmare on Elm Street, a movie which sidestepped the anti-slasher onslaught by turning to the supernatural, a route that Jason himself would soon adopt to no avail.

Mostly sticking to a bog-standard, rinse and repeat, summer camp formula, with a few superficial twists along the way, this was the death knell for the series going forward, each instalment proving more bloodless than the last, which essentially robbed the series of its most potent selling point. Parts V to VII, while upping the self-awareness in a way that maintained a loyal fanbase who, though self-censoring and ashamed of their product, Paramount Pictures would continue to serve, were so heavily edited you’d be forgiven for assuming that whole reels had been accidentally lost along the way.

Inevitably, Paramount’s final foray with one of their most dependable low-budget properties suffered most. Originally set to have several scenes featuring iconic locations in the titular ‘Big Apple’, including one in which Jason leapt off the Statue of Liberty and engaged in a bout of fisticuffs in the world famous Madison Square Garden, the movie was primarily shot in Vancouver, British Columbia, with additional photography in New York’s Times Square and Los Angeles, most of the action confined to a boat.

With unions looking to castigate films with violent sounding titles, especially those with marketable villains, Jason Takes Manhattan even ran into trouble pre-release thanks to the New York tourism committee, who didn’t take too kindly to the above poster, which was replaced following a direct complaint to Paramount, who by that time had decided enough was enough. Jason would live on after Fred Krueger creators New Line Cinema purchased the license with a view to finally pitting Freddy vs Jason, an idea initially pitched by Paramount back in 1987 that wouldn’t see the light of day until 2003. Though that particular movie would prove to be Jason’s most fruitful to date with a worldwide gross of $114,000,000 , Jason Takes Manhattan would perform the poorest, managing $14,300,000 on a budget of approximately $5,000,000. Not a devastating return on what had proved a low-risk nugget, but enough for Paramount to close the doors of Camp Crystal Lake, and the various other locations it took a punt on, for good.

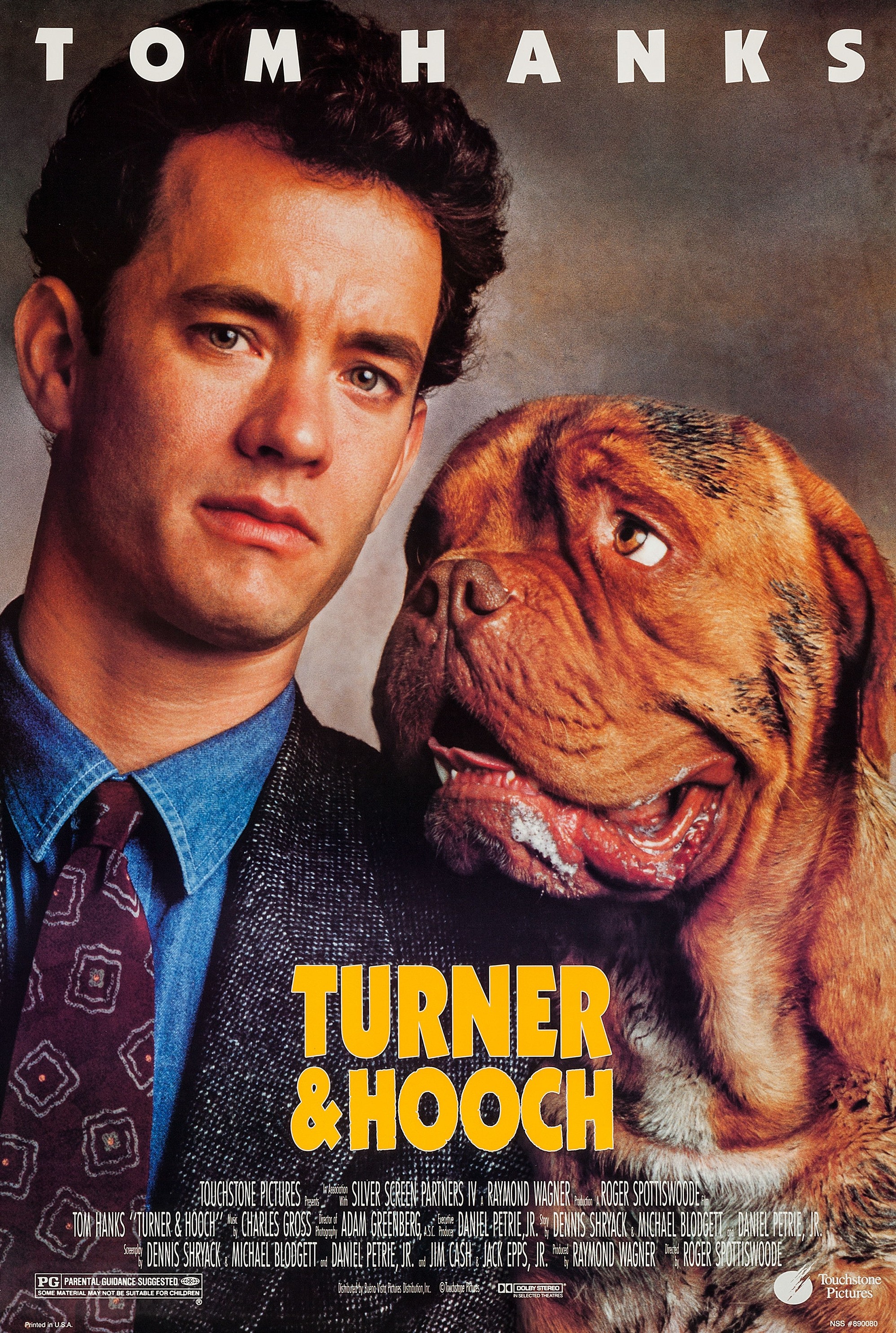

Tom Hanks would continue his rise to the top of the box office with yet another likable performance in 1989’s odd couple, buddy cop comedy with a twist, Turner & Hooch, which, conceptually speaking, was an almost carbon copy of the vastly inferior K-9, starring the late John Belushi’s brother, Jim. Though many believe K-9 to be the plagiaristic culprit, presumably due to its inferior quality, the film was actually released just prior to in April, though both movies were in production at the same time.

Hanks stars as meticulous, set in his ways police investigator Scott Turner, who becomes the reluctant, seemingly temporary carer of a drooling, destructive Dogue de Bordeaux named Hooch after the dog’s old and quite frankly negligent owner and long-time Turner chum, Amos Reed, is murdered by local seafood mogul Walter Boyett (J. C. Quinn) after investigating a disturbance. Though craving more than his quiet, Cypress Beach community has to offer, this forces Turner to put his big city transfer to Sacramento on hold, which results in an everlasting bond with Hooch and even a circumstantial romance with fellow dog owner and veterinarian Dr. Emily Carson (Mare Winningham).

Original Turner & Hooch director and former sitcom star Henry ‘The Fonz’ Winkler was replaced by Terror Train director Roger Spottiswoode during filming after tensions between Winkler and Hanks reached breaking point, a fact that was later confirmed by Winkler’s Happy Days co-star and fellow filmmaker Ron Howard. “It was disappointing,” Howard would tell The Guardian. “I’m friends with them both and both men felt compelled to come to talk to me about it. It was just one of those unfortunate things where they really had a working style that did not fit. I know it was painful for both of them and I was able to lend an ear, if not offer any solutions.” “Let’s just say I got along better with Hooch than I did with Turner,” Winkler would later quip.

Hanks, who had made a name for himself following his star-making turn in Penny Marshall’s 1988, coming of age fantasy comedy Big, is effortlessly relatable in a series of humorous and touching animal domestication scenes that solidified his box office prowess after a less successful lead role in Joe Dante’s hilarious but less mainstream offbeat comedy The Burbs. The actor would become a dependable romcom mainstay in the ensuing years until a career altering turn in 1993’s controversial legal drama Philadelphia, for which he would bag the 1994 Best Actor Oscar. Philadelphia was one of the first mainstream Hollywood films to openly address homosexuality, homophobia, and AIDS/HIV, which had rapidly spread during the 1980s, becoming very much a taboo subject thereafter.

Hanks, who would grow into one of Hollywood’s most versatile actors, is still fondly remembered for his early mainstream comedy period, Turner & Hooch becoming a childhood favourite for 80s kids. Though it didn’t quite match Big at the box office, the movie would prove Hanks’ last big hit for a while, raking in approximately $71,000,000 on a budget of $13,000,000. Hanks’ stock would quickly plummet following a series of mega flops that saw him turned down for the role of Mario in yet another mega flop, 1993’s Super Mario Bros., which proved a lucky escape before his eventual reinvention as a more serious actor.

Top 10 US Domestic Box Office For July 1989

| Movie | Gross | Total Gross | Release Date | Distributor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Batman | $125,186,597 | $251,188,924 | Jun 23 | Warner Bros. |

| Lethal Weapon 2 | $87,404,098 | $147,253,986 | Jul 7 | Warner Bros. |

| Honey, I Shrunk the Kids | $66,736,254 | $130,724,172 | Jun 23 | Walt Disney |

| Ghostbusters II | $35,045,438 | $112,494,738 | Jun 16 | Columbia |

| Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade | $34,542,317 | $197,171,806 | May 24 | Paramount |

| Dead Poets Society | $33,077,748 | $95,860,116 | Jun 2 | Walt Disney |

| The Karate Kid Part III | $30,763,221 | $38,956,288 | Jun 30 | Columbia |

| Licence to Kill | $23,784,818 | $34,667,015 | Jul 14 | United Artists |

| When Harry Met Sally | $23,204,887 | $92,823,546 | Jul 14 | Columbia |

| Weekend at Bernie’s | $21,430,624 | $30,218,387 | Jul 7 | 20th Century Fox |