VHS Revival explores the history of Orion Pictures and the commercial bomb that was Robocop 3

Long before quadrilogies, prequels, reboots and whole cinematic universes, movie trilogies were often the subject of hot debate among movie fans. The likes of Jason Voorhees had already run the sequel concept into the ground by the late 1980s, the Friday the 13th series boasting seven by the decade’s end, but threequels were typically the cut-off point, very few making it that far. Back then the same old questions arose. Did you prefer the Lethal Weapon trilogy? The Die Hard Trilogy? The Alien Trilogy? Today those questions are much more complex, movies such as the Alien vs Predator series and 2013’s deplorable A Good Day to Die Hard considered black sheep by many, and with a fifth Lethal Weapon mooted after action dynamo Richard Donner’s passing, there’s every chance that the series will soon have an unwanted blotch of its own, and that’s assuming you’re a fan of Lethal Weapon 4.

Two huge action movie franchises that never entered that conversation were the Predator trilogy and the Robocop trilogy. The reason behind the first was simple. There was no Predator trilogy, the sorely underrated Predator 2, which swapped the South American wilderness for the sweltering concrete jungle of a dystopian Los Angeles, proving enough of a critical damp squib to put the series on the shelf. Conversely, the Robocop trilogy never really entered the conversation because Robocop 3 was… well, a bit naff. In fact, it became the series pariah for a number of reasons, all of it stemming from the financial misfortunes of a waning Orion Pictures, a production company that was on its last legs by the early 90s after an incredible 80s run that saw them go toe-to-toe with the major Hollywood studios in the action and sci-fi genres, even producing a series of Academy Award winning films during their 1978-1991 heyday.

Orion was founded in the late 1970s after three wantaway executives of the Transamerica-owned United Artists, Eric Pleskow, Arthur B. Krim and Robert S. Benjamin, decided to quit their jobs following a high-profile clash between the parent company and its subsidiary that even made its way onto the pages of Fortune magazine. When Michael Cimino’s epic western Heaven’s Gate tanked at the box office as the once-dominant genre fell into temporary obsolescence, all but condemning Transamerica to the commercial scrapheap, the company was sold to MGM and the rebellious trio cut a distribution deal with Warner Brothers. With a $100,000,000 line of credit, the newly formed Orion, quickly cutting deals with a host of stars that included John Travolta, Jane Fonda, Peter Sellers, James Caan, John Voight, Burt Reynolds and Francis Ford Coppola, were given complete autonomy over distribution and advertising. They also had contractual power over the type and number of films that they chose to invest in. Though this led to successes such as cult comedies Caddyshack and Arthur during those early years, it also led the company to pass on Spielberg’s unbridled smash Raiders of the Lost Ark.

Orion, who would split from Warner Brothers as early as 1982 after TV success with popular cop show Cagney and Lacey, would come into their own during the late 1980’s, though it wasn’t always plain-sailing. In fact, unstable finances would become a hallmark for the company as an independent entity and beyond. Their first year was more hit than miss. Orion would land the domestic distribution rights to Sylvester Stallone smash First Blood ($125,212,904), the first US movie to separate rights across different distributors, after Warner Bros., 20th Century Fox and Paramount Pictures declined due mainly to the Paris Peace Accords, but while ten of Orion’s first eighteen movies turned a profit, most paled in comparison, the closest being 1983’s comedy drama Class.

You know what Bertha says? She says that if we hold back the Rehabs for just two more days, they won’t be able to make us move.

Nikko Halloran

In 1984, Orion turned a corner thanks in large part to James Cameron’s sci-fi sleeper hit The Terminator, which managed a rather significant $78,371,200 on a budget of only $6,500,000, and the Oscar-winning Amadeus ($51,973,029), the latter allowing them an aura of prestige that was previously lacking, though true to Orion’s typical fluctuations in fortune, Francis Ford Coppola’s The Cotton Club was mired in legal troubles, the company losing $3,000,000 million of its investment, which would only add to the film’s woeful returns.

From there affairs grew worse, 1985 proving a horrible year for the company. Though disaster was abated by the hugely popular Madonna’s pop music tie-in Desperately Seeking Susan, Chuck Norris action vehicle Code of Silence and cult horror parody Return of the Living Dead, the year was littered with commercial duds that included the Rutger Hauer-led fantasy adventure The Falcon and the Snowman, Woody Allen’s critically acclaimed but commercially-snubbed fantasy romcom The Purple Rose of Cairo, and former James Bond director Guy Hamilton’s action-adventure film Remo Williams: The Adventure Begins, which, with paltry returns of $12,421,181 on a budget of $40,000,000, forced Orion to abandon what would have been their final production of the year, The Piece Maker. Rodney Dangerfield’s Back to School was also put on hold following the death of a co-producer, which left them without a release for the financially fruitful Christmas season. You could have forgiven the folks at Orion for feeling just a little snakebit.

1986 and 1987, Orion’s peak years, were much more forgiving. Though a slew of underwhelming films were par for the multi-bunkered course, Woody Allen’s next film for the company, Hannah and Her Sisters ($59,000,000 from $6,400,000), and the wildly successful, late-to-the-party Vietnam movie Platoon ($138,530,565 from $6,500,000) would both bag well-deserved Oscars, Back to School ($91,258,000) and Jean de Florette ($87,000,000), the latter picked up for US distribution, both considered huge financial coups for the company, but the movie that many associate with that old Orion Pictures logo, the one that had future franchise written all over it, was Dutch director Paul Verhoeven’s first picture on American shores, the ultra-violent, deliciously satirical Robocop.

Verhoeven, at that time an indie director most associated with arthouse films, wasn’t initially keen, his wife ultimately convincing him that there was much more to the Robocop script than the title suggested. Though drenched in Hollywood excess and very much a mainstream action vehicle, the movie was a scathingly amusing satire at heart, Alex Murphy’s tortured cop-come-authoritarian poster boy a symbol of corporate America’s grip on liberty in a modern capitalist society. The internal struggle between Robocop’s pre-programmed command system and the dying embers of Murphy’s free will allowed the movie an added depth and a novel sense of relatable conflict. Add to this some spectacular costume design from SFX legend Rob Bottin, a superlative score by composer Basil Poledouris, and a stellar cast that included Peter Weller, Nancy Allen, Kurtwood Smith and Miguel Ferrer, and you’re dealing with a bona fide sci-fi classic, a movie that represents the overindulgent, politically suspect 80s as uniquely as anything.

Portrayer Weller, who would become an overnight star following the release of Robocop, worked miracles in creating one of science fiction’s best-loved characters. This may seem like something of an overstatement considering that he spent the majority of the movie hidden beneath bulky, identity concealing armour, but believe me, once you see another actor attempting to pull off the role of OCP’s most noble creation, you tend to acquire an increased appreciation for Weller’s most definitive mainstream performance. In hindsight, it’s astonishing just how much he was able to convey with little more than a taut mouth and a prominent chin.

None of this came easy. Firstly, Weller was far from director Verhoeven’s first choice to play his titular mandroid. Both Arnold Schwarzenegger and Rutger Hauer were considered for the role but were passed upon due to fears that both would look too bulky stuffed into their laboriously fitted, oversized costume. Even Weller, slender and athletic in frame, struggled to squeeze into a suit that took an average of ten hours to fit, proving quite the ordeal for an actor who had no idea what he was getting himself into. Even after weeks of preparation and production-salvaging mime training, dancing around in heavy football equipment to adapt to the physical hardships, he struggled to move, a fact that resulted in the stiff and rigid motions that would come to define the character.

Three years later, Weller would return for Robocop 2, another ultra-violent satire in the Verhoeven mode that, while lacking the satirical refinement of its predecessor, proved something of a cult classic with its unconscionable peewee villains and unrepentant silliness. After Writers Guild of America strikes, potential director issues and a ditched alternate screenplay known as ‘The Corporate Wars’, directing duties would finally go to Irvin Kershner, who had wowed audiences a decade prior with Star Wars sequel The Empire Strikes Back, a much darker effort which many consider to be the finest entry in the ever-expanding franchise. Robocop 2 may have lacked the charm of its predecessor, but it still did more than enough to entertain, our leading man’s performance holding together an often screwy screenplay that saw him turn his back on the role when the opportunity for a third payday came calling.

You called for backup?

Robocop

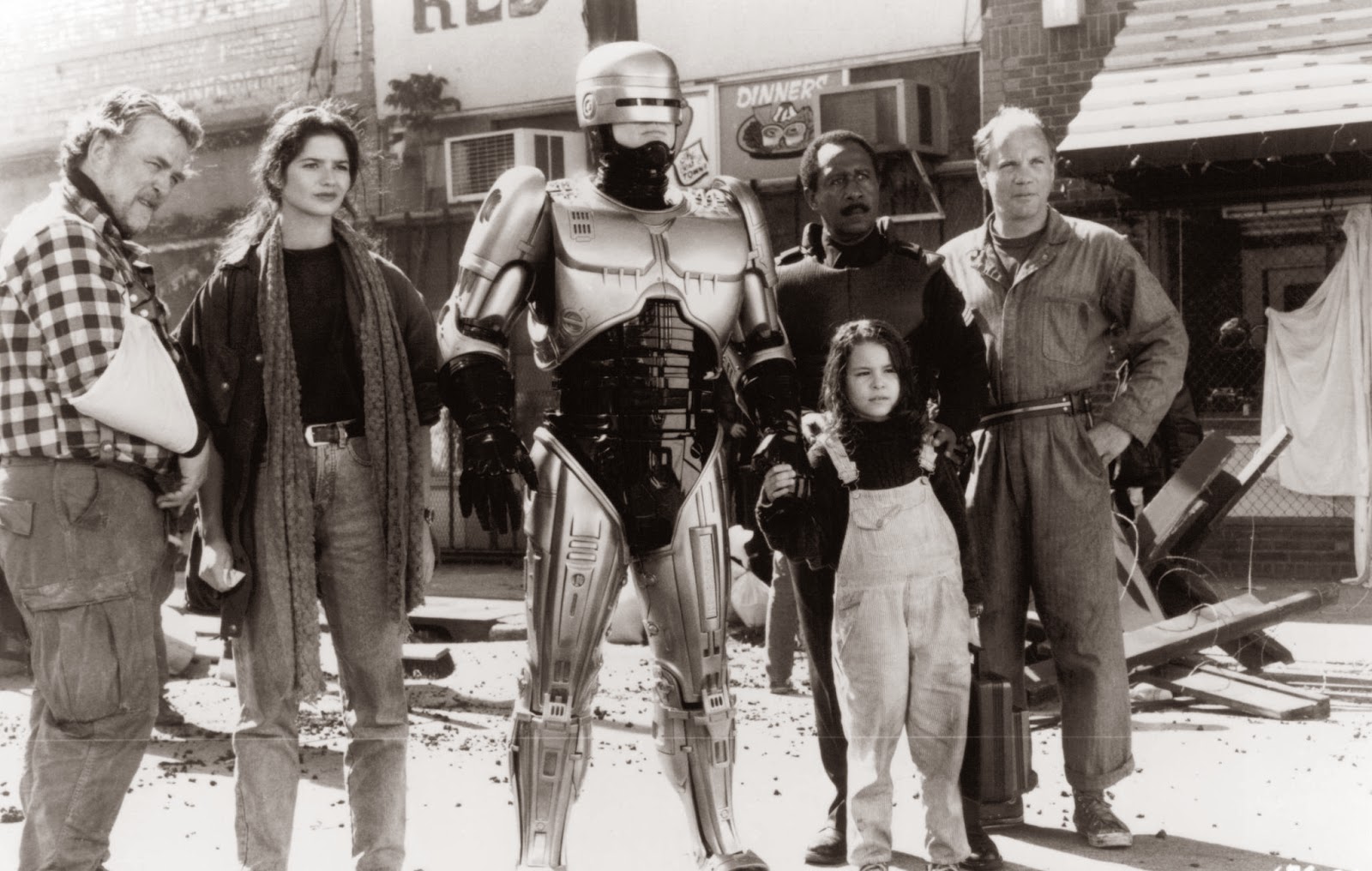

In his place, Orion cast relative unknown Robert John Burke. You may remember him as the eponymous Dust Devil in Hardware director Richard Stanley’s equally fascinating low-budget horror, or as a TV stalwart who has appeared in countless shows, including Blue Bloods and The Sopranos, something that doesn’t happen by chance. That said, I struggled to accept Burke as Robocop. Robocop 3‘s muddled tone and creative lethargy didn’t help matters, and though I have no particular criticisms of Burke as an actor, it just felt off, as if the concept, which many believed had already run its course, had had its heart ripped out. The two have something of a physical likeness, particularly around the all-important jawline, but sometimes it’s hard to separate an actor from a character, and from a personal perspective Weller and Robocop are one and the same.

The second most important actor of the Robocop franchise, Nancy Allen, does return as the ever dependable Officer Ann Lewis, though a part of her would ultimately regret it. Allen had already clashed with Kirschner throughout Robocop 2‘s hectic production, calling it the “worst experience of my life” and citing the director’s script revisions as the reason why the first sequel failed. “The only reason I did Robocop 3 was because the character had such a big fanbase and you feel sort of loyal to the character. I really feel bad for Fred Dekker in a way because I came onto the film after such a terrible experience on the second film and I was very guarded and really not looking forward to doing it.” Cult director Dekker, synonymous with fun, schlocky horrors with a comedic edge, seemed like the perfect choice to lead Robocop’s make or break threequel, particularly with comic book writer Frank Miller returning as co-screenwriter, but the film’s commercial aspirations, designed to tap into tween merchandising, proved to be the movie’s ultimate obstacle.

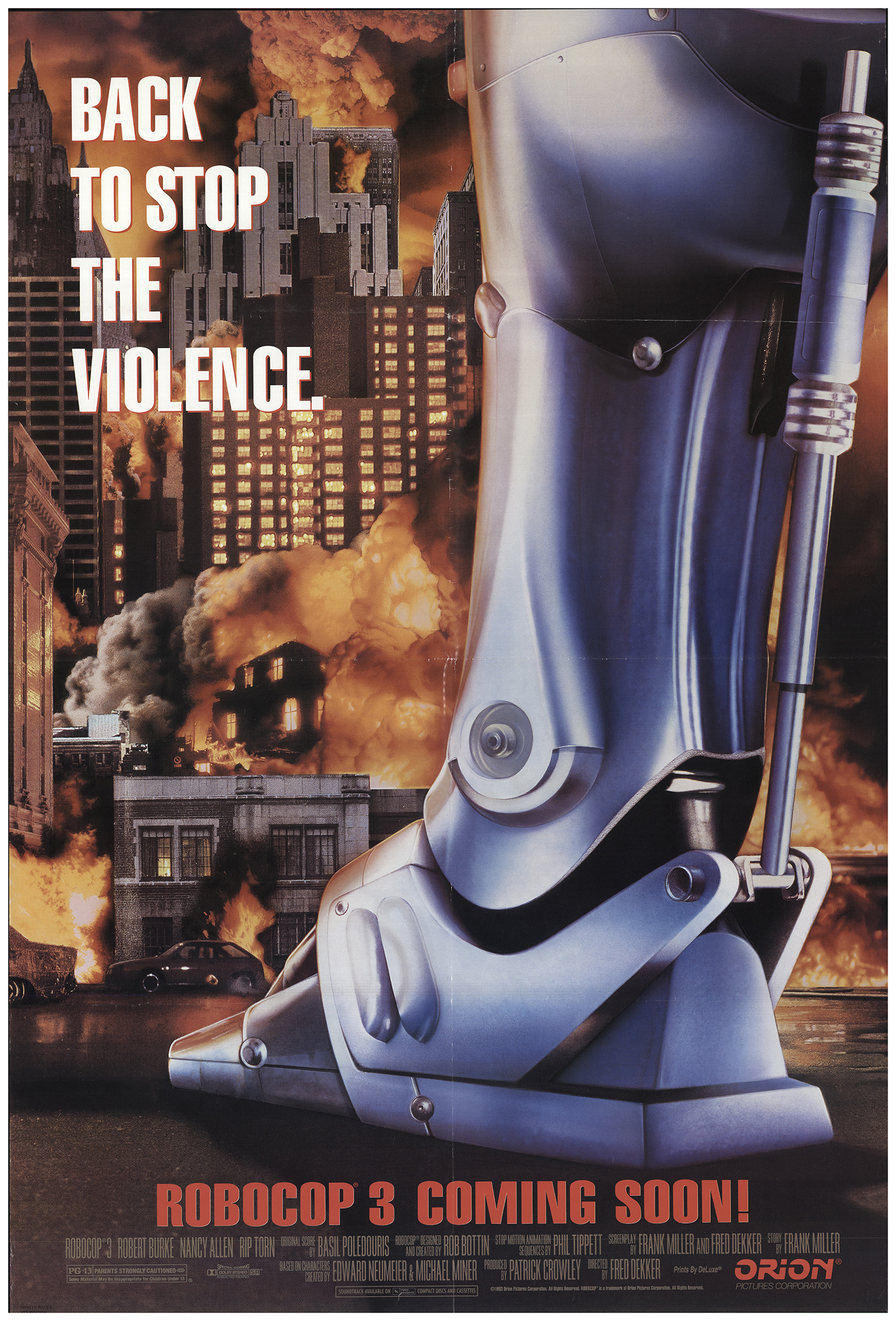

Tonally, Robocop 3 is deeply confused — at least it felt that way to audiences carrying certain expectations. Part of Robocop‘s inimitable charm was its full-throttle, comic book splatter, the kind so hyperbolic that it managed to transcend moral outrage. Sure, it suffered the usual cuts in an era of pedantic censorship, but much like Evil Dead II, released that same year as a response to the previously banned The Evil Dead, most of the violence was able to sluice through based on tone and presentation. This was wisely carried over to the equally violent and self-aware Robocop 2, which while not in the same league as its predecessor, at least understood the essential ingredients that allowed for a somewhat loyal franchise experience. The fact that Robocop 3 was ultimately released with a PG-13 certificate should tell you everything you need to know about the third instalment going in.

The gothic, steampunk qualities that gave the first two Robocop movies their comically sinister vibe and darkly satirical clout are almost completely absent from the third instalment, which attempts to transform our eponymous protagonist into a more conventional superhero courtesy of some toy range-appropriate cosmetic add-ons, most notably the infamous flying Robo, who proves so camp and out of character that he makes Christopher Reeves’ Superman look like Robert Pattinson’s Batman. Even the once fearsome ED-209 is reduced to a comic sideshow, his furious commands wilting under peewee hacker Nikko Halloran’s questionable skills. In one of the movie’s various attempts at a considerably watered down brand of humour, ED, barking his usual repertoire of no-nonsense demands at a gang of underground rebels, is programmed to become ‘as loyal as a puppy’ and duly complies without so much as a circuitry glitch. It’s a sad, glossed-over end for one of the most indomitable villains of the 80s.

In Ed’s place we get the ultra gimmicky,”Otomo” a ninja android developed by the CEO of the Kanemitsu Corporation, an OCP investor who falls into the 80s trend of Japanese bashing seen in films such as Ridley Scott’s Black Rain and even Blade Runner at a time of dwindling American manufacturing and Japanese prosperity. Having acquired the city of Detroit through bankruptcy, OCP’s long standing plans to create the uber corporate, wholly gentrified Delta City is plunged into turmoil. That’s where the Kanemitsu Corporation steps in by purchasing a controlling stake, replacing the morally conflicted Detroit Police Department with McDagget’s ‘take no prisoners’ mob, who begin forcibly removing the city’s residents, until the underground resistance and reprogrammed ally Robocop lead the fight. Otomo is no match for the truly terrifying ED-209, or even Robocop 2‘s deliriously malevolent RoboCain, but he sure had the makings of a cool action figure.

It certainly made sense for the Robocop series to go in that direction, particularly in light of Orion’s severe financial troubles, and to a less obvious extent it already had. The original Robocop may have been a strictly adult affair with absolutely no intent to market the character to kids, but one look at that shiny metal suit and movie-obsessed tykes the world over were instantly smitten. What followed, quite naturally, was a series of comic books, an earlier toy range and even a popular cartoon series beamed into households at a time when cartoons were being created with the sole intent of manufacturing colourful and instantly appealing action figure ranges. With themes of drugs and intense violence, Robocop 2 was again a strictly adult affair on the surface, but with juvenile villains and Robocop’s growing popularity with minors, you have to believe that they already had one eye on the corruptible peewee masses.

All of this pangs of executive meddling, but according to Dekker, whose career was seriously impacted thereafter, that simply wasn’t the case. “There’s a misconception about this movie that the studio steamrolled me into doing something I wasn’t comfortable with,” he would explain. “The truth is, anything wrong with it is entirely my fault. I had a great cast, a great crew, the support of my producers and the studio, and some of the greatest special effects wizards of all time (Phil Tippett and Rob Bottin, among others). I think it really comes down to the script. It was a story by the brilliant Frank Miller, who wrote the first draft—but in the final analysis, it was the wrong story and the wrong script for what an audience wanted from that character. The PG-13 rating didn’t help, since the character’s first two outings were extremely violent and satirical, and that’s really the arena that character belongs in—not a “family” movie.”

Elsewhere, Robocop 3 suffers from an inability to draw anything thematically unique from an already recycled concept. The key to a good sequel is to offer audiences something fresh and rewarding while staying true to the core ingredients that gave the original property its identity. While acting as a continuation of OCP’s nefarious endeavours, Robocop 3 is mostly regurgitation, reintroducing ingredients that have been diluted to resemble a calorie-free, off-brand gruel. Sure, Murphy’s internal battle with corporate edicts and his last lingering thread of humanity, this time unfurled by an underground resistance battling for survival during a period of police state brutality and heartless gentrification, unavoidably resurface, but aside from a host of new faces made up of some rather notable TV actors that include The Shield’s CCH Pounder, we’ve been here before. It’s difficult to blame Dekker and co. As brilliant as the original movie is, perhaps there’s little more that can be done on an emotional level with a character in Robocop’s rather specific and limiting predicament. If that isn’t the case, it has yet to be proven otherwise.

Other than gimmicky, toy-friendly villains, the one character who personifies Robocop 3‘s more child-friendly approach is preteen hacker Nikko. Much like Newt from Aliens, a character who raised the ire of Alien fans who saw her as a soppy commercial by-product, she acts as a plot device to unearth Murphy’s long-lost paternal qualities. While that idea worked wonders in Aliens, allowing the newly no-nonsense and distrusting Ripley to care for another human being, drawing maternal parallels between her and the xenomorph queen, here it just feels tacked-on and superficial, a dynamic that is completely at odds with what audiences had come to expect from the series. Conversely, Rip Torn is a hoot as a character simply credited as ‘The CEO’, exuding a slippery, obsequious arrogance that Robocop 3 could certainly have used more of.

As sex with a cybernetic organism would have proven problematic to say the least, there is no room for a serious love interest in Robocop 3, despite the casting of an impossibly beautiful Jill Hennessey as Dr. Marie Lazarus, one of the scientists who supposedly helped create OCP’s most conflicted hybrid organism, which makes the addition of a child ally almost inevitable, particularly in light of the departing Lewis, who is brutally, some would say mercifully, put out to pasture by Paul McDaggett and his ruthless army of Urban Rehabilitators or ‘Rehabs’, a somewhat unimaginative moniker that, a priceless corporate suicide from an OCP high-rise notwithstanding, recalls the wicked ironies of previous entries as much as anything that is on offer. Still under OCP command and unable to protect Lewis thanks to his ‘Fourth Directive’ programming, an excruciatingly maudlin, anticlimactic death scene ensues between Murphy and Lewis. It’s a tepid end for a once lovable character and an actor whose heart clearly isn’t in it. Despite the reappearance of Robert DoQui’s Sergeant Warren Reed and Felton Perry’s OCP executive Donald Johnson, once Lewis checks out, which is surprisingly early in the movie, Robocop 3 hardly feels like a Robocop movie in the traditional sense.

Let’s gentrify this neighborhood, build strip malls, fast food chains, lots of popular entertainment. Whadda you think?

The CEO

Despite the undoubted potential of one of the most iconic characters of the 1980s, Robocop 3 did pitiful numbers at the box office, managing a paltry domestic gross of $10,696,210 on a budget of approximately $22,000,000, putting the Robocop franchise on the shelf until 2014’s instantly forgettable reboot did the same. The failure of their most viable franchise punt further burdened Orion’s continued fiduciary concerns, but it was a small part of a much bigger problem. Robocop 3, which was shot all the way back in 1991 and set for release in the summer of 92, was famously delayed as the company attempted to eke out an existence. So bad and in the public spotlight were affairs in early 1991, about the time that Robocop 3 was entering production, that Academy Awards host Billy Crystal mocked the studio’s debt problems during his opening monologue, joking that “Reversal of Fortune [is] about a woman in a coma, Awakenings [is] about a man in a coma; and Dances with Wolves [was] released by Orion, a studio in a coma.” It was an ignominious time for a company that was once considered a major Hollywood player.

Following unsuccessful buy-out talks with a burgeoning New Line Cinema, Republic Pictures and the newly founded Savoy Pictures, Orion were at their lowest ebb. This was further compounded by the fact that The Silence of the Lambs, a movie developed and distributed by Orion, would sweep the 64th annual Academy Awards, which was too little too late for the company as key executives and valuable talent had already abandoned ship, making a miraculous comeback highly unlikely. Crystal, returning as host of the ceremony, would take another swipe at Orion, only this time you could sense a touch of sympathy in his delivery. “Take a great studio like Orion: a few years ago Orion released Platoon, it wins Best Picture. Amadeus, Best Picture. Last year, they released Dances with Wolves. Wins Best Picture. This year The Silence of the Lambs is nominated for Best Picture. And they can’t afford to have another hit!“

By the fall of 92, Orion had re-emerged from bankruptcy with an agreement that allowed them to produce and release films using outside financing, the studio purchasing the distribution rights after completion, but once again their output was more miss than hit during their four-year bankruptcy protection. Purchased by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in the late 90s, their existing library of classics central to the deal, Orion’s corporation status was kept in tact as a way to swerve MGM’s distribution agreement with Warner Home Video, Orion surviving in various forms until they were officially reinstalled as a standalone brand in 2017, becoming a theatrical marketing and distribution branch. In 2018, Orion Classics was revived as a multiplatform distribution label through the United Artists Releasing banner, their first such project being Lars Klevberg’s thematically updated reboot of Tom Holland’s horror classic Child’s Play.

On May 26, 2021, online shopping monolith Amazon announced the $8.45 billion acquisition of MGM, their vast video library an essential resource for their Amazon Prime Video catalogue, many of those classics emerging from Orion’s unpredictable but memorable past. While their distribution endeavours were brought to a swift end after Amazon closed the door on UAR’s operations in March of 2023, Orion’s movies live on. Some were terrible, others, like Robocop 3, were deeply misguided failures, but with multiple Oscars and some of the finest, most celebrated movies of the 20th century to their name, there is no denying their legacy, something that both MGM and Amazon clearly agreed with when mining their considerable contributions for audiences old and new. You’d certainly buy that for a dollar.

Director: Fred Dekker

Screenplay: Frank Miller &

Fred Dekker

Cinematography: Gary B. Kibbe

Music: Basil Poledouris

Editing: Bert Lovitt

The poor performance of Robocop 3 and the subsequent fate of Orion Pictures makes for fascinating reading. Great piece. The deck was really stacked against Robocop 3 from the start. Robert John Burke wasn’t a great fit to take over the role of Robocop, he was great in Dust Devil though, now there’s a great low budget horror film! The pacing of Robocop 3 is all over the place, it had some good concepts, but it all got so diluted in the production hell of the movie.

LikeLike

Hi Paul. Cheers!

Orion’s history is fascinating. Crazy that a company, responsible for so many classic films, can have such an unstable financial history.

Robocop 3 isn’t a classic film by any means. It was a complete misfire. Their attempts to transform the Robocop character into a superhero for kids was not what.audiences wanted, as Dekker himself theorised.

A poor end for the character (unless you count the utterly pointless reboot).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, totally agree. Robocop 3 was a bust, even the great concept of the whole jetpack thing ended up looking cheap and silly! Wasn’t there a 4 part TV mini series afterwards, as I recall. That was very watered down as well, but think it had two Robocop’s fighting or something? There was a really good Robocop comic series from IDW as well, that was really good, shame it didn’t last for long. I didn’t think much of the Robocop reboot either.

LikeLike

A TV series? Robocop vs Robocop? That’s news to me. It sounds like it would have been really watered down. I vaguely remember the comic books. I may have read a couple. I’m sure I liked them.

I was really into The Punisher and Judge Dredd comic-wise. Those were the two I bought regularly. The Punisher featured a mini series Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade comic strip around the time of the film’s release if I remember correctly.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah, the Robocop TV show was the family-friendly TV series from 1994. There was a 4 part mini series in Robocop Prime Directives in 2001 that was a move back to the grittier version of Robocop, that’s that one that had Robocop fighting another Robocop. It was pretty good as I recall. Think it was on Amazon Prime recently as well. The comic series was pretty cool, still have the whole run of those. I liked Punisher and Judge Dread as well, great characters!

LikeLike