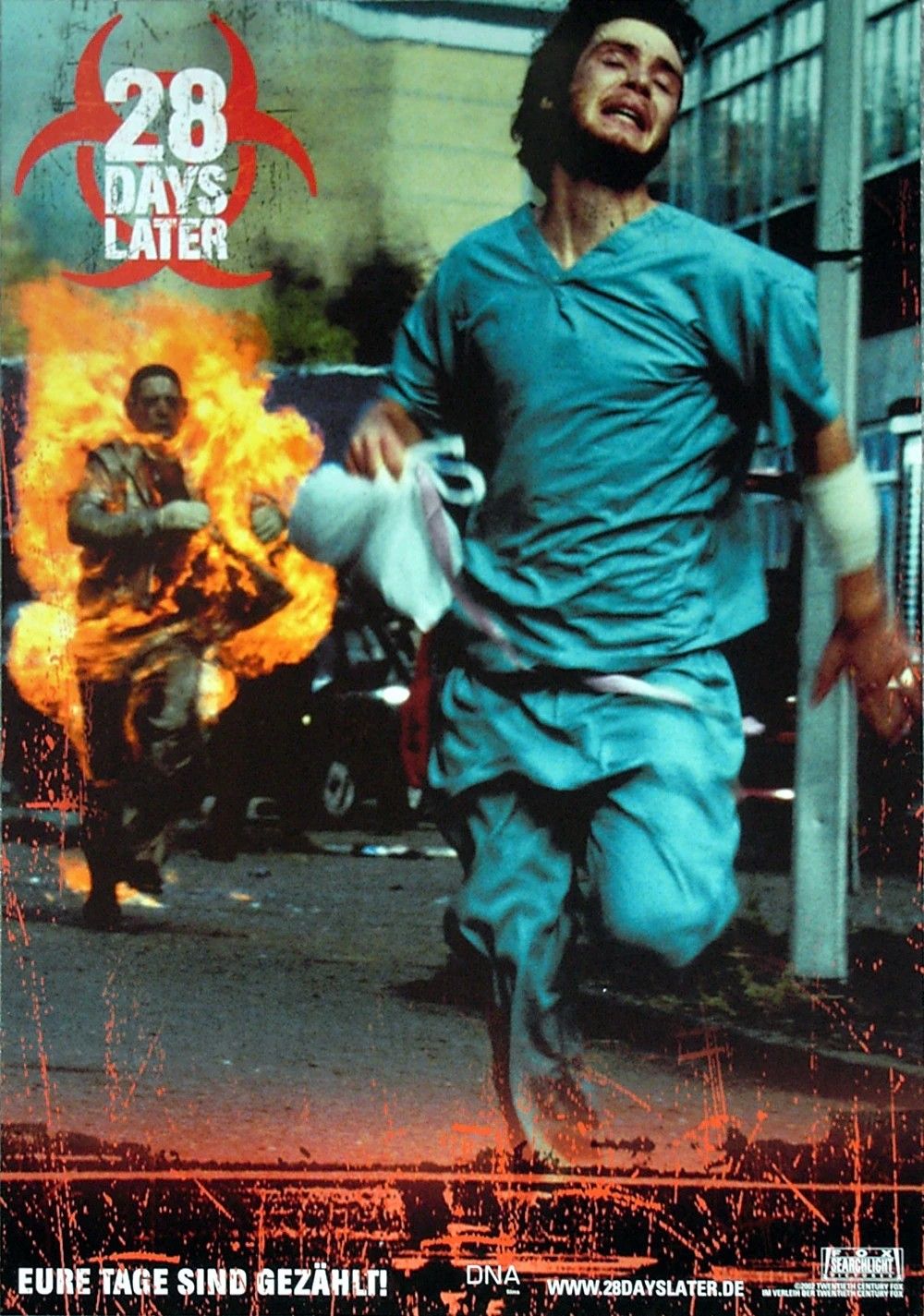

Director: Danny Boyle

18 | 1h 53min | Horror, Sci-fi

When it comes to quarantine viewing, you just can’t beat zombie movies. We can relate to the isolation, find hope with a group of strangers working together, and take comfort in that no matter how bad things are outside your door, at least no one is trying to eat you. Building the atmosphere of isolation is something zombie movies really excel at. From Romero’s early Dead Trilogy to last year’s Little Monsters, zombie flicks almost always involve a group either making their way through a deserted, dangerous environment or holed up for tenuous safety in a confined location. Often, it is a combination of the two.

Danny Boyle’s 28 Days Later is a sterling example, and the fact it is not technically about zombies only adds to its current relevance. By making his mindless fiends still-living humans suffering from a highly contagious virus, Boyle grounds his movie a little closer (though still not that close) to reality. For those who don’t know, the film shows the aftermath of a pandemic caused when animal rights activists break into a government biological testing lab, unwittingly releasing the Rage virus into the human population (thanks PETA). A single drop of infected blood can—within seconds—turn a person into a super-agro killing machine. The Infected lose all rational thought, feel no pain, have zero self-preservation instinct, very little regard for hygiene, and go after uninfected folk like a heat-seeking missile. For all intent and purpose, zombies. In some ways, though, their motives are even purer. They don’t want to munch you guts or eat your brain, they just want to beat you down.

The most famously eerie part of the movie is the beginning, as Jim (Cillian Murphy), freshly awoken from a coma, wanders the empty streets of London. It’s always impressive when a production transforms a bustling city into a ghost town, as Night of the Comet did with Los Angeles, The Walking Dead did with Atlanta, or The Quiet Earth did with, uh, all of New Zealand. It is particularly impressive that Boyle was able to close down some of London’s most famous locations, like Piccadilly Circus, for such a comparatively low-budget film.

Such scenes produce a psychological dissonance; we’ve been wired to picture those cities teaming with life, with their own personalities and character. Nothing pounds in the feeling of isolation more than watching a lone survivor quietly roaming the abandoned streets in broad daylight. This is why when I watched the recent footage of drones silently hovering down the empty streets of New York, Paris and other quarantined cities around the world, I immediately thought of 28 Days Later. I wonder how long it will be before we start seeing those same clips show up as stock footage for future apocalypse flicks.

Boyle’s questionable decision to shoot on shitty looking DV tape and the modest scope of the script cannot hide the director’s talents. The movie is both tightly paced and emotionally engaging, which can be a tricky balance with this sort of thing. Murphy does a fine job as the awkward hero, and Brendan Gleeson is about as lovable as he as ever been as a dad just trying to keep his daughter safe and happy. Top marks go to Naomie Harris for her knockout performance as tough-as-nails survivor Selena, who slowly learns to let down her shield and connect with her new, makeshift family (while remaining a total badass). Cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle pulls off some surprisingly arty shots, playing with reflections, lighting, and perception to get around the limitations of the cheap format.

28 Days Later occupies the rare position of being both heavily influenced and influential. Avoiding the literal undead freed Boyle from being so slavish to the Romero model, but the structure itself dips heavily into his original trilogy. The third act is practically a pocket-sized Day of the Dead with less overacting. The abandoned streets also harken to the various incarnations of I Am Legend, as does the suggestion that the Infected don’t dig the daylight.

Not that there’s anything wrong with imitation, but Boyle gives as good as he takes. 28 Days Later reinvigorated the zombie genre practically overnight. Fast zombies, while not new (Return of the Living Dead featured zombies that could not only run, but direct traffic) became all the rage. The opening to The Walking Dead, both the comic and the show, is almost a direct lift from this movie. More importantly, though, Boyle’s use of ugly but cheap DV inspired a generation of amateur filmmakers to pick up consumer grade cameras and start shooting.

Of all the plague movies we are reaching for in the time of the coronavirus, 28 Days Later is perhaps the most genuinely reassuring. This is because, in the theatrical ending, at least, there is a light at the end of the tunnel. The epilogue jumps several weeks after Jim’s awakening, where we see the single-minded Infected have begun to starve to death. A jet plane also flies by, suggesting some part of the civilized world still functions. For the survivors, life can begin to get back to normal. Until the sequel, at least.

Rock-On

One of my favorite marriages of scene and score comes from the movie’s climax, where Jim sneaks into the refuge of some rape-minded soldiers in order to save Selena and Hannah. John Murphy’s “In the House – In the Heartbeat” begins slow and quiet, but as the chaos in the house grows, so does the intensity of the droning guitars. By the time Jim gives the vile Corporal Mitchell a well-deserved and shockingly gory eyeful, the emotional wall of sound is so powerful the distinction between infected and human behavior is virtually gone. It’s one of those moments that leaves you needing to catch your breath.

Light At the End of the Tunnel?

What is the suicidal allure to a highway tunnel in apocalyptic movies? They are dark, claustrophobic, and 100% certain to contain the exact kind of nasties that you are running away from. Still, Brendan Gleeson’s Frank somehow decides it to be the best route out of London, despite Jim plainly stating that it is a terrible idea. Against all reason, Frank not only enters the gaping maw of death, but races his taxi through the debris-clogged path like he’s whizzing around a fucking go-kart track. At least until he blows a tire halfway in and almost gets the whole group—including his teenage daughter—mobbed by a stampede of Infected. Leave the navigation to cooler heads, mate.

Artistic Licence

As seen by Jim, painted on the wall of a church turned makeshift morgue: “The End Is Extremely Fucking Nigh.”

Who says the faithful don’t have a sense of humor?

Expertly directed and completely engrossing,

Chris Chakais just the film we need these days. It emphasises the need for proper social distancing, shows that we all need to look out for each other in a crisis, and above all, reminds us not to be a dick. Highly recommended viewing inside or outside of quarantine.