Ranking the vile, often ridiculous exploits of one of horror’s most enigmatic figures

Fred Kruger has always been the stuff of nightmares, though the reasons for making us scream would range from innovative exploits in horror filmmaking to horrific acts of tween marketing. For many, Robert Englund’s ‘bastard son of 100 maniacs’ was one of the most memorable and enigmatic figures of the 1980s; for others he was a short-lived obsession as Freddy fever exploded in a powder keg of commercialism.

The character went from sadistic child killer to stand-up comedian in a series that lasted a decade, dividing fans into two main types: those who preferred the character’s distinctly evil incarnation and those who got their kicks out of his wisecracking horseplay and fantasy-led, practical effects extravagances, but you’d be hard-pressed to find a person on the planet who hasn’t heard of Fred Krueger, whatever their opinion of the character.

In this article, VHS Revival ranks one of the most notable horror franchises of the 20th century.

7. A Nightmare on Elm Street 5: The Dream Child (1989)

Some of you are perhaps wondering why Freddy’s Dead isn’t rock bottom on this list. Admittedly, that instalment was guilty of exacerbating its predecessor’s flaws on just about every conceivable level, diluting things even further while spreading the commercialism on thicker, but by that point there was no turning back; the series was already dead, and it was 1989‘s A Nightmare On Elm Street 5: The Dream Child that should be held responsible.

A year earlier, the franchise had hit its commercial zenith with A Nightmare on Elm Street 4: The Dream Master, putting Krueger on the kind of mainstream plateau rarely glimpsed in the horror genre, but like all commercial trends the bubble was growing too vast and distorted to maintain, and the inevitable pop would turn eyes red with disbelief. The movie also boasts the lowest kill count of the franchise with a record-equalling three victims, an indictment of a series which had descended into little more than a platform for silly practical effects set-pieces. Instead we are treated to a kind of Gothic fantasy, one so illogical it makes Joel Schumacher’s Batman and Robin seem insightful. All that’s missing is the canned laughter.

The Dream Child does irreparable damage to a character who once breathed new life into the slasher. Gone are Freddy’s gunslinger stance and sadistic cackle, replaced instead by a walking Christmas cracker packed with cheapskate jokes that would leave a giddy infant yawning. On the subject of Batman and Robin, it even throws in a Krueger variation known as “Super Freddy”, a shameless plug for Innovation Publishing’s short-lived comic series, which would lead the company to bankruptcy by 1992.

The movie’s premise is just ridiculous: Krueger attempts to possess Alice’s unborn child with the intention of being born back into the real world, a place where his powers and dreamworld omnipotence will no longer exist. If his only goal is to kill children, why not remain exactly where he is, a realm where he is above the law and seemingly immortal?

Ultimately, it’s difficult to understand exactly who this movie is for. Krueger was already a pop culture phenomenon in 1989, and though the movie is rated R and various anti-violence groups had made their presence felt, it is apparent by its fantastical tone and the kind of ruthless merchandising that resulted in Freddy dolls and kids pajamas that it was partly made with a preteen demographic in mind, even if it did visually elaborate on a backstory explaining Krueger’s birth as the result of the gang rape of a nun in a mental asylum. I mean, really?!

Ultimately, The Dream Child turns us into passive consumers motivated by manufactured buzz. It occasionally intrigues with its absurd plot developments and some admittedly impressive gothic imagery and practical effects, but 1989’s A Nightmare on Elm Street is a shameless brand with a faltering sense of identity.

6. Freddy’s Dead: The Final Nightmare (1991)

In many ways, New Line Cinema’s fifth Krueger-led sequel is the very worst of the bunch, though those of you who prefer Robert Englund’s sillier portrayal — and I know you’re out there — may see things differently. The movie also makes the mistake of trying to provide a humanising backstory for the kind of supernatural entity that suffers for it. We find out that not only did Krueger marry, he even fathered a young daughter named Katherine. Not only is this paternal notion queasy, it is handled with the subtlety of a rhino juggling tea cups on a circus tightrope.

By the time of Freddy’s Dead: The Final Nightmare‘s release in 1991, the series had been reduced to a micromanaged farce of shameless and horror-defying commercialism. Krueger had gone from gleefully sadistic to second-rate stand-up act in the seven years since we were introduced to a barely-glimpsed evil haunting the periphery of Tina Gray’s grungy boiler room nightmare. Back then he was all mystery. Here his past is laid out in mystique-crushing detail. Not only is this the cheapest and most transparently throwaway of the series, it belongs to the early ’90s, a time when horror’s stock had plummeted to its lowest level in decades.

Like The Dream Child before it, Freddy’s Dead is a fantasy-driven platform for a series of practical effects set-pieces that lack the visual ingenuity of previous instalments, though never have they been more flamboyant, and to the movie’s detriment. Among the slapstick crimes are a hyper-referential approach that would lampoon the likes of The Wizard of Oz with the puerile abandonment of Leslie Nielsen’s post Naked Gun exploits, Freddy even reaching for a push broom in the guise of a wicked witch in what is essentially a pantomime act.

The movie would also turn cinema’s most infamous child killer into Wile E. Coyote for a Road Runner inspired kill involving an air balloon and a bed of nails, but even worse is the sight of Krueger adorning a Nintendo-style power glove to commit the ultimate in horror buffoonery: death by video game. If all of that wasn’t enough to cheapen Freddy’s ostensible send-off, New Line even turned to the always desperate 3-D gimmick to fool punters into one last splurge, deeming us worthy of only 15 minutes of through-the-screen action. Oh, and there are celebrity cameos — lots of them. Roseanne Barr and Tom Arnold, anyone?

5. A Nightmare on Elm Street 4: The Dream Master (1988)

When it comes to the rose-tinted lens of horror nostalgia, The Dream Master inhabits the candy cotton clouds of pixie stick land. So anticipated was New Line’s third sequel that it became the most successful in the series until the release of Freddy vs Jason more than a decade later. Ironically, it was Friday the 13th producers Paramount Pictures who first approached them with the idea of a franchise crossover in 1987, though Jason’s waning stock presumably didn’t appeal to the decision makers over at New Line Cinema while Freddy was still hot property, leading Paramount to produce the faux Carrie crossover Friday the 13th Part VII: The New Blood.

For many Freddy fanatics who grew up in the late 80s, The Dream Master is the first movie that comes to mind. For those who weren’t around to witness it, it’s difficult to convey just how popular Robert Englund’s once-terrifying child killer had become, particularly with younger movie fans. In 1988, Krueger was everywhere: adorning teen magazines, starring in commercials, appearing on talks shows; he even fronted his very own pop video for the painfully corporate rap song “Are You Ready For Freddy?” by the Fat Boys. You couldn’t turn around without seeing pop culture’s flavour of the month partaking in some kind of commercial tomfoolery.

Having said that, The Dream Master is a marked improvement on those instalments so far included, and as a pop culture phenomenon there is no denying its impact. It also features some of the best practical effects set-pieces in the series, particularly a death sequence in which one unlucky victim is transformed into a cockroach, a spectacle that proved so expensive that other deaths had to be re-evaluated as a cost-cutting measure (this was the reason why Rick would test his karate skills against an invisible Freddy in a quite ludicrous scene). The movie was also directed by Die Hard 2‘s Renny Harlin, whose idea was to transform Freddy into a wisecracking hero in the James Bond mode, so there’s no lack of action, but as a horror flick it barely fails to qualify.

There is still much to denounce about the fourth instalment in the A Nightmare on Elm Street series. It is the first to feature a paper-thin cast who are almost surplus to requirements. It also eschewed the kind of perverse horror that had been central to the franchise for elaborate set-design and general buffoonery, embracing Freddy’s transition from sadistic monster to fast-lipped antihero and all-round merchandise machine. The movie was more concerned with commercial tie-ins and pop culture promotion than appealing to horror fans, and though it would launch the character to a mainstream stratosphere that would see an ever prosperous New Line dubbed ‘the house that Freddy built’, creatively it sacrificed sure-footing for a killer stroke.

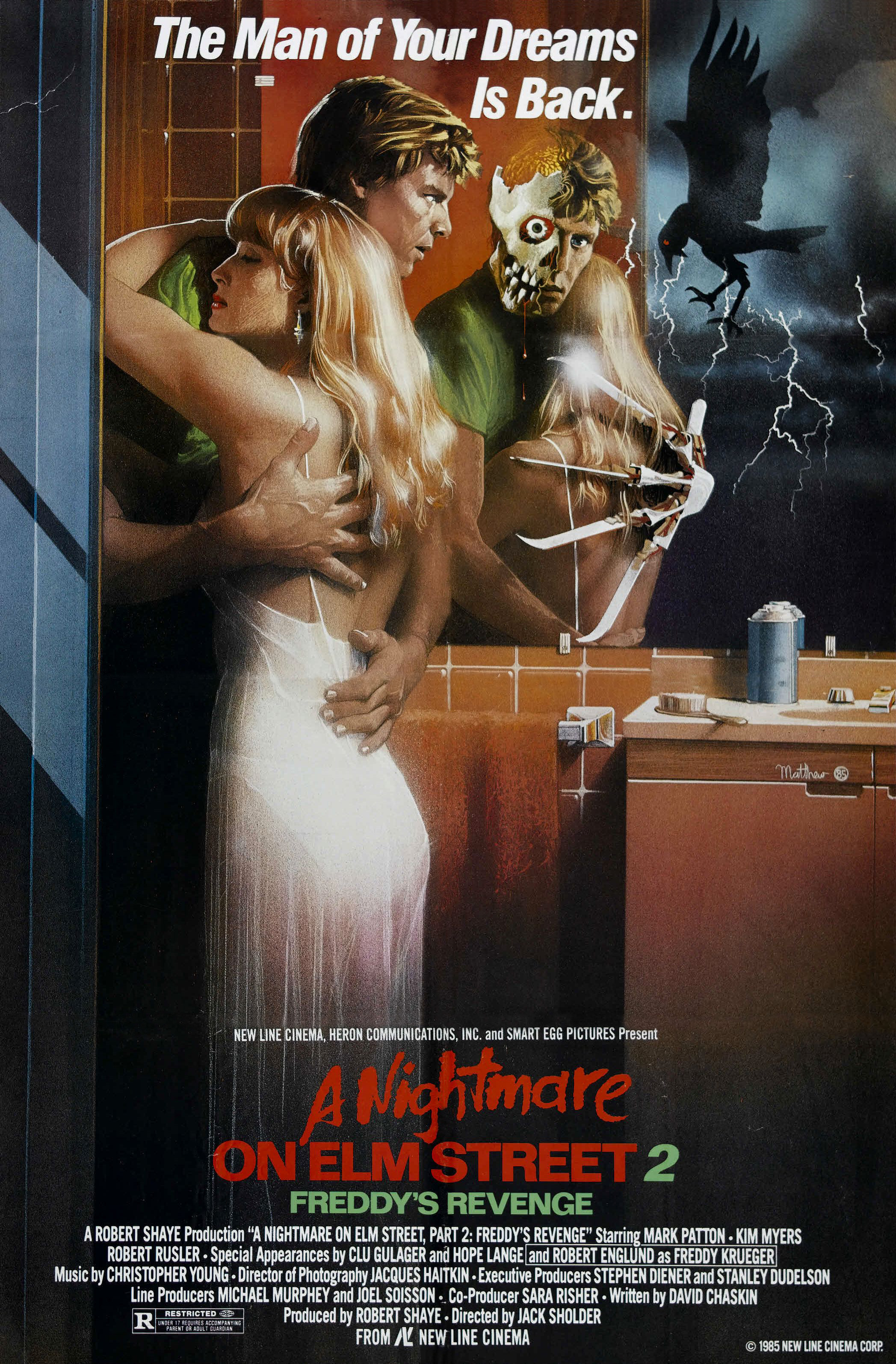

4. A Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddy’s Revenge (1985)

It’s safe to say that Freddy’s Revenge is the most divisive instalment of the A Nightmare on Elm Street series, so it seems only fair that the movie should land right in the middle of this ranking. Personally, I have something of a love/hate relationship with a movie which has garnered quite the cult following, not least because of the adverse effect it had on the fledgling career of ‘final boy’ Mark Patton, a closeted actor in an AIDS driven era of homophobia who somehow found himself in a ‘gay panic’ movie.

One thing you can’t deny about Freddy’s Revenge is its sense of intrigue. This is an anomalous franchise entry if ever there was one, but despite its silliness and inability to successfully tap into Craven’s dreamworld concept, or adhere to its own internal logic, it is never less than a fascinating curio, with a strong protagonist and a Krueger variation who has never looked scarier. Freddy almost looks feral in this one; rabid like a nicotine addicted bloodhound on an insane rampage. In fact, it is arguably the last time the character was truly terrifying.

There are other positives to be found in Freddy’s Revenge. First and foremost there is the film’s protagonist, Jesse, a hugely conflicted ‘final boy’ struggling with his own sense of sexual identity. Much has been made of the apparent gay subtext in Freddy’s Revenge, which for years was flat-out denied by the film’s writer, but it makes for the kind of inner conflict that Krueger thrives on as he sets about returning to the real world (will he ever learn?). There are also some stand-out moments that prove truly creepy. An opening nightmare sequence involving a school bus captures Krueger’s omnipotent evil beautifully, and Grady’s death, one that sees Krueger shed Jesse’s corpse like a silk gown, is one of the absolute best in the series. Also, a special shout-out to Robert Rustler as doomed confidant, Grady. That guy was infinitely watchable in everything he starred in.

Unfortunately, there are also some rather dubious decisions that make Freddy’s Revenge something of a misfire. Director Jack Sholder’s decision to ditch the original movie’s dreamworld concept for what is essentially a straight-up possession story didn’t make much sense from a creative or commercial standpoint, nor did ditching Charles Bernstein’s gut-wrenching original theme. Hellraiser‘s Christopher Young gives us a typically inspired alternative, but Bernstein’s scathing lullaby defines Freddy so well; it’s a fundamental part of the character’s identity. They even considered ditching actor Robert Englund for a cheaper alternative until a few takes convinced them otherwise, another sign that they didn’t quite realise what they had on their hands. Beyond those omissions, there are also numerous plot holes and some deeply unscary moments that are borderline silly. Something of a hodgepodge, but never less then fascinating, for better and for worse.

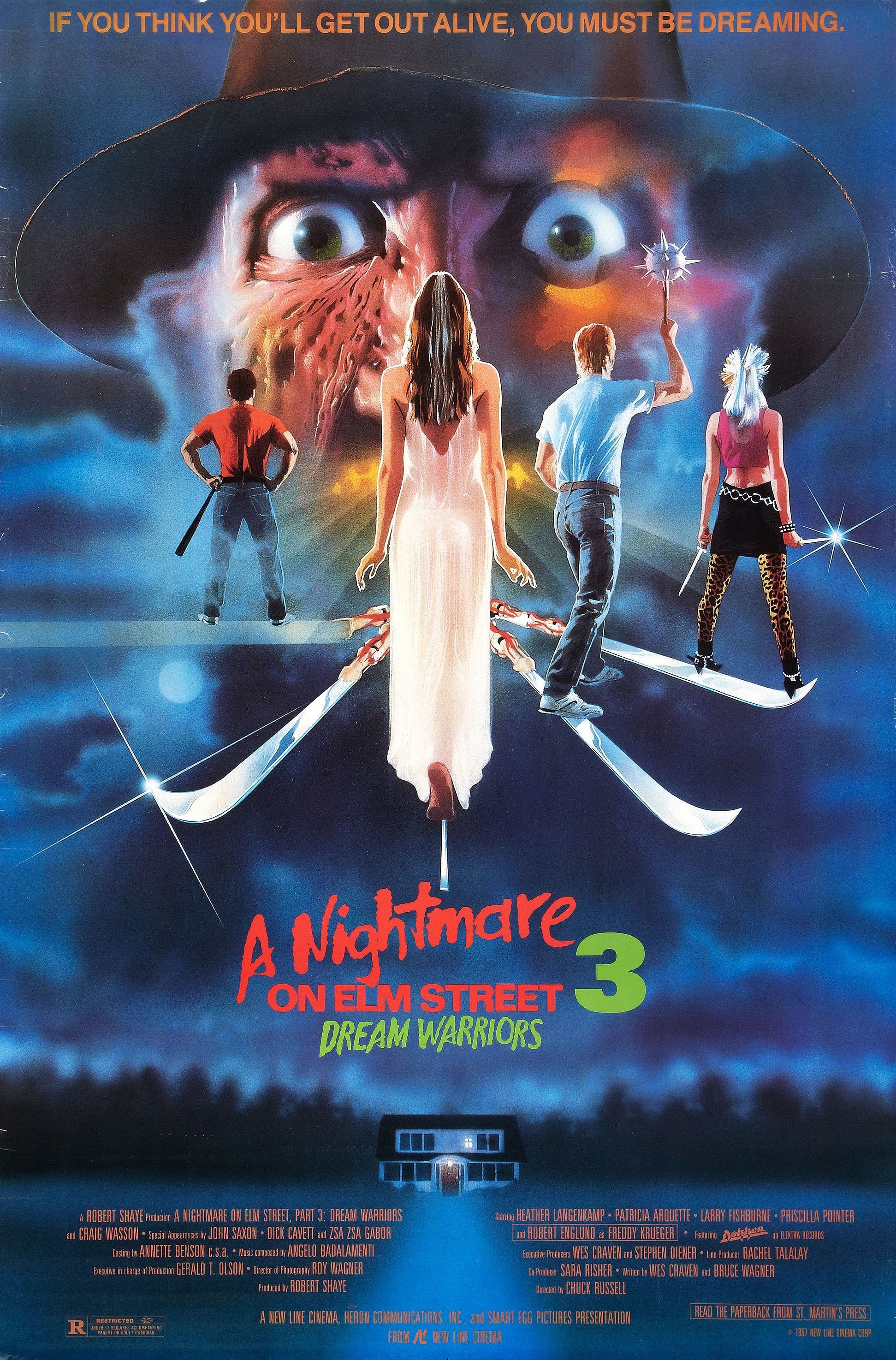

A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: The Dream Warriors (1987)

For many, A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: The Dream Warriors is the absolute pinnacle of the series. After the middling indecisiveness of Freddy’s Revenge, which almost put the series on the self as early as 1985, something was needed to revive a potentially money-spinning prospect that was at risk of slipping into slasher mediocrity, and after Wes Craven’s (apparently much darker) screenplay was subjected to heavy redrafts by director Chuck Russell and long-time collaborator Bruce Wagner, something magic happened.

Many feel that The Dream Warriors steered Krueger away from the darkness towards the realms of mystique-crushing celebrity, and there is no doubt that the third instalment set the franchise on a path to commercial glory and everything, good and bad, that went with it, but as a mediator that melds fans of Freddy’s evil and comical sides respectively, The Dream Warriors gets the balance right, resulting in a film that re-establishes Craven’s original concept and expands on it tenfold, allowing for an open canvas of dreamworld delights where anything and everything seems possible.

The movie is set in a psychiatric ward where original final girl Heather Langenkamp returns to the fray as a doctor who naturally specialises in sleep deprivation, Freddy no longer able to run the rule over a ward of insecure teens who tick all the right boxes as potential prey: young, disillusioned and consistently patronised for their wild claims of some barely-glimpsed boogeyman. This leads to a quite incredible series of practical effects and cute one-liners that would soon define horror’s most infamous degenerate. Welcome to prime time, bitch!

In a sense, The Dream Warriors began the rot by exploring commercial avenues that would one day exploit the series to within an inch of its life, American hair band Dokken penning the movie’s MTV-driven theme song, and though it may prove a little too fantasy-driven for fans of the character’s darker side, the third instalment gives us the best of both worlds and is the reason behind the character’s mainstream apotheosis. Ultimately, the movie both redesigns and rediscovers, which is more than anyone can ask for in a sequel.

Wes Craven’s New Nightmare (1994)

A decade after the release of the original A Nightmare on Elm Street, Wes Craven was fighting to salvage the integrity of his most iconic creation after submitting to New Line honcho Robert Shaye’s desire for a sequel, a decision that somewhat tarnished the original instalment’s potential as a true masterpiece, giving birth to one of horror’s most inexhaustible franchises. The filmmaker has to shoulder some of the responsibility, but as the indie production company continued to branch out, the character transcended his control, and big business tends to take on a life of its own.

At the time of its release, Wes Craven’s New Nightmare would slip under the commercial radar somewhat, becoming by far the least successful movie in the series. The film was a fresh and unorthodox meta experiment that would prove the blueprint for Craven’s more marketable 1996 smash Scream, but audiences — especially those weaned on a diet of Krueger’s sillier period — were distinctly unprepared for its unique perspective and, as a result, didn’t really care for it. Only years later was the movie reassessed as something of a conceptual innovator.

New Nightmare has aged incredibly well; yet another testament to the visionary qualities of the late Wes Craven, who would return to direct his most famous creation for the first time since the original instalment. Much like Scream, New Nightmare is a movie within a movie, one that sees the once imaginary Krueger cross over into reality as ‘the entity’, a demon who haunts members of the original cast as Craven pens his latest ‘sequel’, one that begins to spell out the fate of its stars before they’ve even signed up for the project.

Watching New Nightmare, it quickly becomes apparent just how important Craven is the integrity of the character. The antithesis of the haphazard instalments that inspired it, the director is in total control, once again blurring the lines between dreams and reality with an expertise that is positively spellbinding. There are so many parallels and cute nods between the ‘reality’ of New Nightmare and the fictional world of Fred Krueger that before long the two are almost indistinguishable. By the time this revamped version of the character crosses over into the realms of reality, he has reclaimed a terrifying aura long-since buried.

New Nightmare is still somewhat divisive among fans of the series, and though it admittedly loses its way during its practical effects heavy finale, after years of watching Krueger dwindle in the creative doldrums, Craven has finally got his baby back, and it’s an absolute scream.

A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984)

Slashers had become somewhat stagnant by the mid-1980s, but Charles Bernstein’s scathing lullaby teased something unique and terrifying as one of horror’s most indelible creations haunted the fringes of the subconscious. It’s incredible that Craven’s dreamworld concept had not been dreamt-up prior to 1984, but like all the best ideas they seem so obvious after the fact. This was grungy, cerebral filmmaking, the kind that would transform New Line Cinema from a struggling indie company into a mainstream giant that would one day produce the colossal Lord of the Rings franchise.

So many things set the original A Nightmare on Elm Street apart in an era of tired slasher clones. Its unique concept, the kind that would lead to an inexhaustible slew of worldwide imitators, would breathe new life into the horror genre. Craven’s scholastic attention to detail and ability to tap into the human condition, along with some inspired makeup and practical effects, gave that concept an air of authenticity which belied the film’s humble budget. The problem with many ‘Nightmare’ instalments is that they never really feel like a dream in a manner that we can relate to. That wasn’t the case with the original A Nightmare on Elm Street, Craven’s visual trickery plunging us into an ethereal realm of mind-bending uncertainty.

The characters Craven created were also a cut above your typical slasher fodder. Each of the Elm Street kids has conflict beyond the context of their peril and can all be easily identified with. When Jason’s latest victim wanders senselessly into the woods and begins tripping over, we perceive that character as stupid and look upon them with knowing derision. With A Nightmare on Elm Street it is different. The characters are drawn to their demise not by stupidity or contrivance, but by a universal weakness that we can all relate to.

Then there’s Krueger himself. On the surface, he may have been just another marquee attraction in the Michael Myers mode, but there was something very distinct about him. He wasn’t the kind of barbarian who would dispose of you with one brutish blow. For him the thrill was in the chase. The act itself was merely a form of ejaculation. Just as important to the Krueger character is the man who portrays him. Jason Voorhees has been continuously recast to varying degrees of success, but try separating Englund from Freddy at your peril. The actor lives and breathes the character. Without him, there is no Krueger.

How many other characters can claim to have built a Hollywood production company almost single-handed? How many fictional child killers have transcended the realms of horror to become an unlikely hero to kids the world over? That’s the universal appeal of one of the most iconic figures in genre history, and whether you like your Krueger tongue-in-cheek or of the darker persuasion, and even if you don’t care for him very much at all, you all know exactly who he is and where he came from. And, as always, sleep is just around the corner.

Sweet dreams, bitches!