Controversy creates cash in Paul Verhoeven’s ultra-violent sci-fi classic, an indictment of greed, corruption and the struggle for basic human freedoms

Robocop was something of a baptism of fire for filmmaker Paul Verhoeven. Before making the switch to Hollywood in search of the American dream, the Dutch filmmaker was renown for art house projects that were very much grounded in reality, 1973‘s romantic drama Turkish Delight bagging a Best Foreign Language Film nomination at the 45th Academy Awards. His first film on US shores, 1985‘s Flesh and Blood, was a low-budget historical adventure that did pitiful numbers, but Robocop was a different prospect entirely; the antithesis of all that went before both creatively and commercially. That’s not surprising given the fact that the movie’s protagonist is a half man, half machine with a spectacularly gaudy 80s costume design, a clunky Rob Bottin creation that would immobilise actor Peter Weller to such an extent that it determined the nature of the Robocop character.

Orion Pictures, who had a reputation for being hands-off during productions, were always open to ideas and very trusting of its employees, but they began to worry when shooting was set to begin and the Robocop costume still hadn’t arrived on set. Things got worse, particularly for star Peter Weller, when he realised he not only had to wear one suit, but two, which became a long, laborious process that hindered the schedule even further. “And then the suit came in… there’s a wetsuit and an inner suit. It took me three hours, while shooting, to put on the inner suit. And then another seven hours to put on the outer suit. That’s ten hours,” Weller would lament. “And it was on a Friday…I lost my mind.” To make matters worse, the design was hugely flawed, almost impossible for the actor to adapt to. “Rob Bottin was extraordinarily nervous because the thing was not working; looked great but was not working. We shot one little scene… I don’t have control of the arms yet. I really didn’t know how to work the suit. It’s not really light so I’m trying to fight it. It’s a mess. We all kind of fell apart.”

The suit’s awkward design became such a problem that Verhoeven, who didn’t have a great relationship with Bottin to begin with, threw a “shitfit”, threatening to fire everyone involved. He was serious too, so much that Orion, who were now envisaging another big financial blow in a notoriously spotty era, almost pulled the plug on the project. In their desperation, Orion flew in Israeli mime artist and movement coach Moni Yakim, who Weller credits for saving the entire picture. “[Moni] is the only voice of reason. And he really saved this film… because while [the crew] are flipping out, Moni goes up to Rob and Paul and says, ‘What can we [cut out]? Can we cut out the elbows? Can we cut out the wrists, all the joints? Cut out the rubber, just tear it out.’ And then he started removing pieces of the [titanium plastic]. Then he pulled out the bottom of the shoes… and the backs of them. And finally he made something I could barely start to move in.”

Moni remained a beacon of calm as the first day of shooting approached, his experience as a visual artist proving essential to the character’s mannerisms. As Weller would recall, “[Moni] took me aside… every crisis is an opportunity… and said something that made this more organic for me… Moni’s just calm, man…he said, ‘listen, you have to slow everything down. You have to make it really, really exaggerated. Don’t fight this thing. It’s never gonna be liquid… You have to make each one of these moments really slow, like a big head-turn. And I said, ‘Man, it just feels so phoney. It doesn’t feel hip. It feels like bad opera. And he said, ‘Do it. Even bigger…Pulling the gun: bigger. Head: bigger… And we shot 40 minutes of tests: walking, turning, pulling out the gun. I go out of the place and say, ‘I don’t know, Moni. He said, ‘Peter it’ll be absolutely perfect.’ Much like Stan Winston’s equally iconic Predator, Robo was originally pitched as an elusive machine with snake-like abilities. The character’s movements have since become so iconic that it’s difficult to imagine any other visual conception.

You call this a GLITCH? We’re scheduled to begin construction in six months. Your “temporary setback” could cost us fifty million dollars in interest payments alone!

The Old Man

The movie’s overtly comic tone was something else that was partly determined by outside forces. Robocop is excessively violent, and in an era of cinematic censorship it was only inevitable that the censors would come calling. Most disconcerting was a scene in which the movie’s protagonist is systematically mutilated by a series of highly graphic shotgun blasts and the director’s overt ‘concentration on pain’. Even today that scene is shocking to behold, not just for its vindictive acts of violence and perverse sense of degradation, but for its wild west lawlessness and sense of unbridled anarchy. It was nothing new to see cops gunned down with such insouciance, but those characters were generally faceless extras, or at the very least died honourably. Murphy’s savaging at the hands of the movie’s villainous rabble is an act of inhuman disdain that chills you to the bone. The film was rejected for an R rating an incredible eight times before finally shedding enough gore to please the Motion Picture Association of America, a fact that caused Verhoeven’s artistic vision to become somewhat compromised.

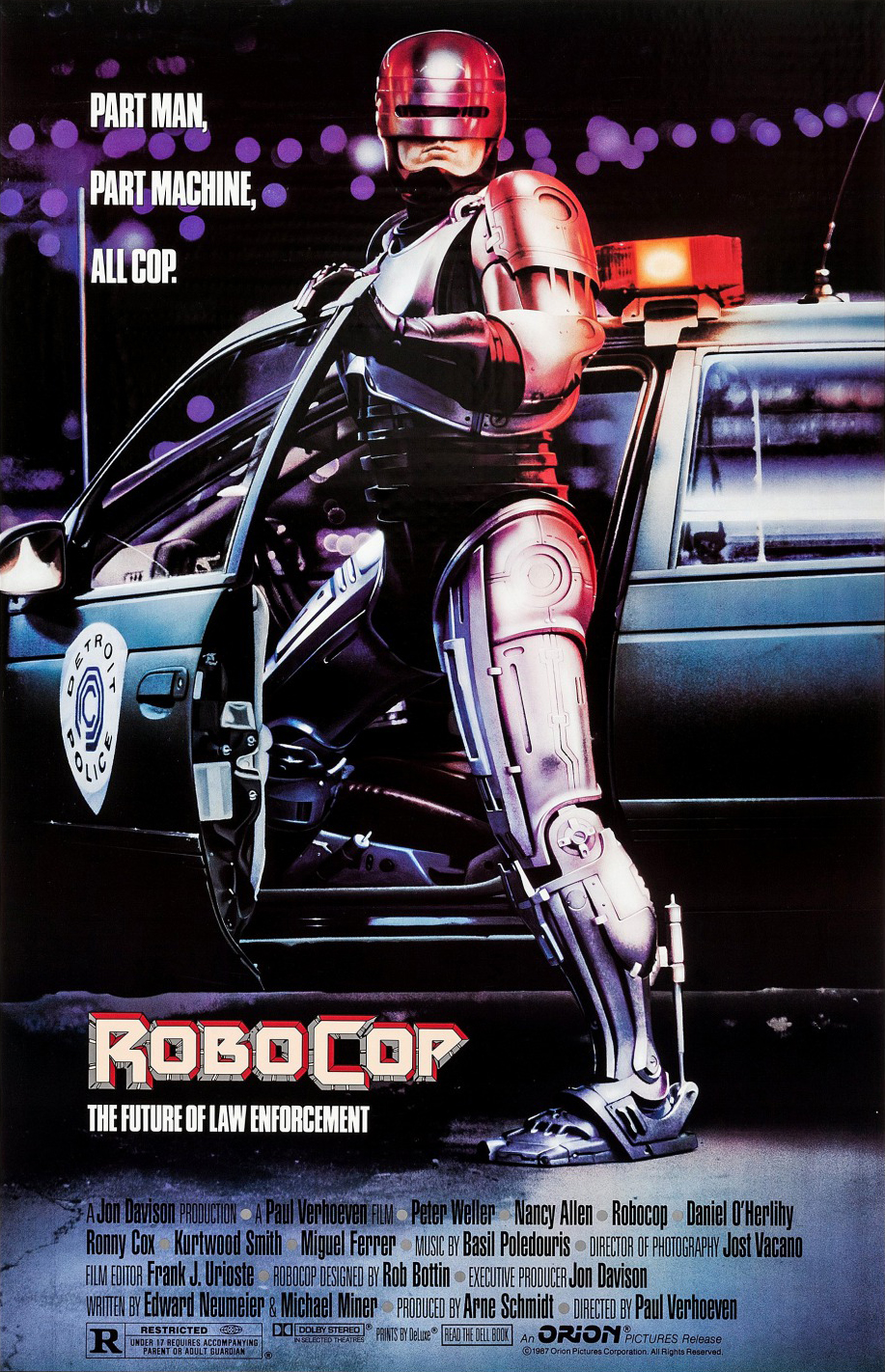

What remains is still incredibly graphic, even by today’s standards, but Verhoeven’s cartoon approach and deftly woven subtext softens the movie’s extreme nature, not just aesthetically but politically, transforming the movie into a Cyberpunk gorefest similar in tone to the 2000 AD comic book series, from which, one suspects, it drew at least a modicum of inspiration. The Robocop character is a marvel of costume design, the kind of emblematic figure that was destined to wow watching kids the world over, the character’s eventual dumbing down for the tween demographic ultimately lampooned in the largely disappointing Robocop 2, but in the mind of Verhoeven this was a strictly adult affair, a conscious exploitation of our most primal urges and the commercial blueprint for all future US productions.

Unsurprisingly, the theatrical cut was not violent enough for the director, who felt that the film’s graphic extremities punctuated its transparently fictional nature in a way that set it apart, providing an ironic commentary on 80s movie violence through overindulgence. Perhaps the most notoriously graphic set-piece featured in Robocop — asides from Murphy’s O.K. Coral style mutilation — comes at the beginning of the movie when an executive meeting unveils Robocop’s mechanical nemesis, ED-209, a problematic machine whose unfortunate malfunctioning sees a boardroom lackey blasted into oblivion as heartless corporate ambition stumbles for self-preservation.

ED-209 is the ultimate symbol of corporate oppression, a colossal wonder of stop motion model work which enforces the will of private power with a single-mindedness that can only lead to disaster, though its propensity for malfunction highlights the hypocrisy inherent. The machine is the very embodiment of autocratic control, an irrepressibly destructive purveyor of death who dishes out cold, hard justice with the unflinching gusto of a Dickensian poorhouse owner. A set-piece that would see actor Kevin Page fitted with an incredible 200 blood squibs was deemed far too explicit for general consumption, several cuts made in order to make the scene more palatable, but for many the screenplay’s observational ironies are enough to justify the all-out bloodbath, are in fact part and parcel of Verhoeven’s delectably immoderate assault on Reagan-era sensibilities.

Most of those ironies come in the form of the movie’s sociopolitical commentaries, which were strikingly innovative back in 1987. Robocop may give us thinly-drawn stereotypes of black-and-white delineations, but the cartoon rampage of Clarence J. Boddicker and company is a byproduct of corporate greed and political corruption, giving us a United States entrenched in nuclear threat and a society squirming under the thumb of mega corporation Omni Consumer Products. Their goal is to privatise law enforcement and turn Detroit into a police state known as Delta City, an authoritative stronghold that threatens to shield high-level corruption from any and all consequence while the common man squirms in a cesspit of poverty and unrepentant violence. It’s a dead-on critique of not only modern society, but the era in which Robocop was forged.

In 1987, this was all a thinly-veiled commentary on Reagan’s America, whose privatization revolution would see trillions of dollars’ worth of state-owned enterprises end up in the hands of investors. Oliver Stone’s Wall Street would explore similar territory that same year, Michael Douglas’ unscrupulous stock market player Gordon Gekko manipulating unions in an attempt to dissolve an airline and sell off its assets. The 80s promoted greed and personal advancement, an attitude that would lead to great financial disparity, unemployment, poverty, homelessness and street crime, and with the wholly hypocritical ‘War on Drugs’ putting more low-income minorities in jail, what hope did the next generation have of carving out a future for themselves?

Though Kurtwood Smith’s wonderfully malevolent Boddicker provides the face of Detroit’s city in dissolution, it’s Ronny Cox’s Dick Jones who rules with an iron fist. Jones is next in line for the executive throne, and when smug upstart Bob Morton (Miguel Ferrer) challenges his position following the Jones-led ED-209 debacle, rushing through his innovative and wholly inhumane Robocop project, Jones turns to the very streets that he publicly condemns in order to deal with the problem, offering Boddicker the keys to the city’s criminal underbelly in return for straight-up muscle. Boddicker’s gang are a pack of crazed hyenas running roughshod over a city teeming with all-out rebellion, the kind of savage grunts Jones wouldn’t wipe off his designer boot heel, but every war needs a public enemy, and Clarence’s ragtag gang of sociopaths are more than happy to take the lucrative bait.

As a sociopolitical satire, Robocop delves even deeper, lampooning the tenuous nature of global relations and the surreptitious influence of a privately-owned media, smiley, matter-of-fact newsreaders reporting on accidental disasters caused by a US satellite dubbed The Peace Station, a ‘Strategic Defence Peace Platform’ which fires on America’s own and leaves downtown Santa Barbara engulfed in flames. It is George Orwell with an 80s twist. All of this is echoed by misogynistic TV shows and brazen advertisements selling nuclear war-based board games, the film’s nightmarish vision woven into the very fabric of its fictional society. So commonplace is the threat of all-out destruction that news coverage has become blasé, in-your-face family entertainment. It’s somewhat ironic that Robocop would spawn its own toy range and animated TV series.

Can you fly, Bobby?

Clarence Boddicker

For those who are familiar with his US body of work, such themes are all very Verhoeven, but the filmmaker often works on existing material that he doesn’t write himself, and Robocop falls into that category. In fact, Robocop was first pitched all the way back in 1982 after screenwriter Edward Neumeier saw the iconic poster for Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner and was told by a friend that the movie was “about a cop hunting robots”. Neumeier had already written an unrelated treatment about a robotic police officer which would later develop into the story of a robot with a computerised mind that developed human tendencies. In 1984, Neumeier met music video director and eventual co-writer Michael Miner, who had been working on a similar idea. He even had a rough draft of a project entitled SuperCop about a severely injured police officer who becomes a donor for a cybernetic organism.

In a Q&A session with The Film Society of Lincoln, Verhoeven admitted to having very little to do with the movie’s political content. Having only arrived in the US in 1985, the Dutch filmmaker “jumped into the movie”, and was almost completely unfamiliar with the American politics of the day, attributing much of the screenplay’s content to the movie’s writers. Naturally, the concept seemed just a little silly to potential investors, until Orion, fresh off the heels of unbridled Arnie smash The Terminator, decided to take a punt, a risk that paid off for everyone involved. Made on a budget of approximately $13,000,000, Robocop would open at number 1 at the US box office, an opening weekend of $8,000,000 topping Stanley Kubrick’s late to the party Vietnam epic Full Metal Jacket and Cannon’s ill-fated mainstream splurge Superman IV: The Quest for Peace. The movie would go on to gross $53,400,000 during its initial North American run, with a further $24,036,000 in VHS rentals the following year, leading to a decade of unbridled success for Verhoeven.

Verhoeven, who was comfortable in his European bubble, had never envisaged or even entertained such a career path. In fact, it was something of a surprise when producer Arne Schmidt approached him after both Repo Man‘s Alex Cox and Kenneth Johnson, creator of the hugely popular sci-fi series ‘V’, turned down the project. Verhoeven was similarly perplexed, throwing the first screenplay he received straight in the trash. The filmmaker wasn’t keen on such high-concept action fare, only reconsidering after his wife pointed out that there was much more to Robocop than meets the eye.

Speaking to Esquire in 2014, Verhoeven would explain, “I was feeling insecure at first about RoboCop as it was unlike anything I’d done before. My wife and I were on holiday in the Côte d’Azur, and I read a page or less of the script. I felt that it was very, how shall we say, Americana, not so much for me. I went for a long swim, and my wife had been reading the script all that time. She said to me, “I think you’re looking at this the wrong way. There’s enough there, soul-wise, about losing your identity and finding it again.” I didn’t recognize that in the beginning. That was the main issue: finding the philosophical background to the film, because I couldn’t find it. It was so far away from what I was accustomed to making.”

Verhoeven would find inspiration in the works of Dutch artist Piet Mondrian, a pioneer of abstract art who would claim that “Art is higher than reality, and has no direct relation with reality,” a quote that sums up the movie’s presentation as a whole. Mondrian’s Composition with Yellow, Blue and Red shows black horizontal and vertical lines cutting through colourful geometric shapes, an image which would form the basis of the film’s abrupt depiction of the modern media. Discussing the various media-based social commentaries that permeate Robocop‘s central narrative, the director would claim, “The elements were already [in the script], but I felt they should be there as abruptly as possible… cut right into the main narrative. Interrupt the main narrative.”

Made during the ‘bigger is better’ era of yuppie America, Verhoeven’s amped-up formula was just the ticket, fuelled by the kind of unabashed controversy that invariably sells tickets. That formula would become increasingly prevalent in the director’s subsequent movies, including ultra-violent Phillip K. Dick adaptation Total Recall and highly sexualized efforts Basic Instinct and Showgirls. Those films were developed with controversy in mind, leading Verhoeven to conclude that, “These two elements [sex and violence] are the most important of everything.” At its heart, Robocop is exploitation cinema masquerading as big-budget extravaganza, a movie elevated by superior storytelling and production values, but one lubricated with the kind of cinematic sleaze that would have most films dismissed as B-movie trash.

Of course, there is much more to Verhoeven’s US debut, the violence a commercial wrapper for something more cerebral. A family man left for dead while attempting to apprehend a gang of criminals, Verhoeven would describe protagonist Murphy’s journey as a “Christ story” during an interview with MTV in 2010, even going as far as dubbing the Robocop character as “the American Jesus”. “It is about a guy that gets crucified after 50 minutes,” he explained, “then is resurrected in the next 50 minutes and then is like the super-cop of the world, but is also a Jesus figure as he walks over water at the end.”

What’s the matter officer? I’ll tell you what’s the matter. It’s a little insurance policy called “Directive 4”, my little contribution to your psychological profile. Any attempt to arrest a senior officer of OCP results in shutdown. What did you think? That you were an ordinary police officer? You’re our product, and we can’t very well have our products turning against us, can we?

Dick Jones

Murphy certainly has something of the Martyr about him. Transformed into an indestructible machine, he still retains much of what makes him human as he becomes OCP’s flagship product, their ownership of his salvaged spirit symbolising corporate America’s grip on free will in a modern capitalist society. Scenes in which a newly transformed Murphy is gawked at by suits and lab coats as they toy with his very soul are heartlessly condescending and overbearingly claustrophobic, his man-made psychological profile installed with a series of convenient ‘product violations’ that leave him powerless when confronting senior officials at OCP. In an era of online censorship, systematic propaganda and political absolutism, the themes that drive Robocop are as relevant as ever.

Inevitably, Murphy begins to recall scenes from his old life, not only regarding his former wife and son, but also the gang of miscreants who altered his life irrevocably, starting him on a path of anarchic destruction that will ultimately lead to OCP’s top brass and a battle to salvage his last lingering thread of humanity. Though both Verhoeven and Neumeier are left-leaning politically, many of the latter’s friends saw Robocop as a fascist movie, and in some ways the character is a walking irony, violently enforcing the law with pre-programmed edicts that read like a public information film. Looking to integrate their multimillion-dollar investment into everyday society, Murphy’s high-tech incarnation is quickly transformed into an overnight celebrity as OCP’s propaganda model pollutes the airwaves, ‘Robo’ posing as their poster boy for a safer future.

This raises the kind of moral questions that establish our protagonist’s true sense of conflict: an internal struggle between Robocop’s pre-programmed command system and the dying embers of Murphy’s own freewill. This is beautifully highlighted during a scene in which Murphy’s only ally, Officer Anne Lewis (Nancy Allen), helps him rediscover his human touch after his target system falters, resulting in a quasi-romantic scene that sees Murphy liberate himself by blasting containers of the very baby food that symbolise the character’s total degradation at the hands of his corporate parents.

Stripped of its comic book storytelling and violent overtones, it is this internal conflict that makes the Robocop character such an enduring one. Murphy has lost his own version of the American dream to those who build their empires on the misery of others, and in the ultimate irony it is the semi-automated will of OCP’s most imperial creation that is left to sift through the hostile garbage and hit corporate ambition with a heavy dose of hard-earned humanity.

Your move, creep!

Director: Paul Verhoeven

Screenplay: Edward Neumeier &

Michael Miner

Music: Basil Poledouris

Cinematography: Jost Vacano

Editing: Frank J. Urioste