The newly genericised slasher may have lead to creative stagnation, but when it came to realistic depictions of death, nothing was further from the truth

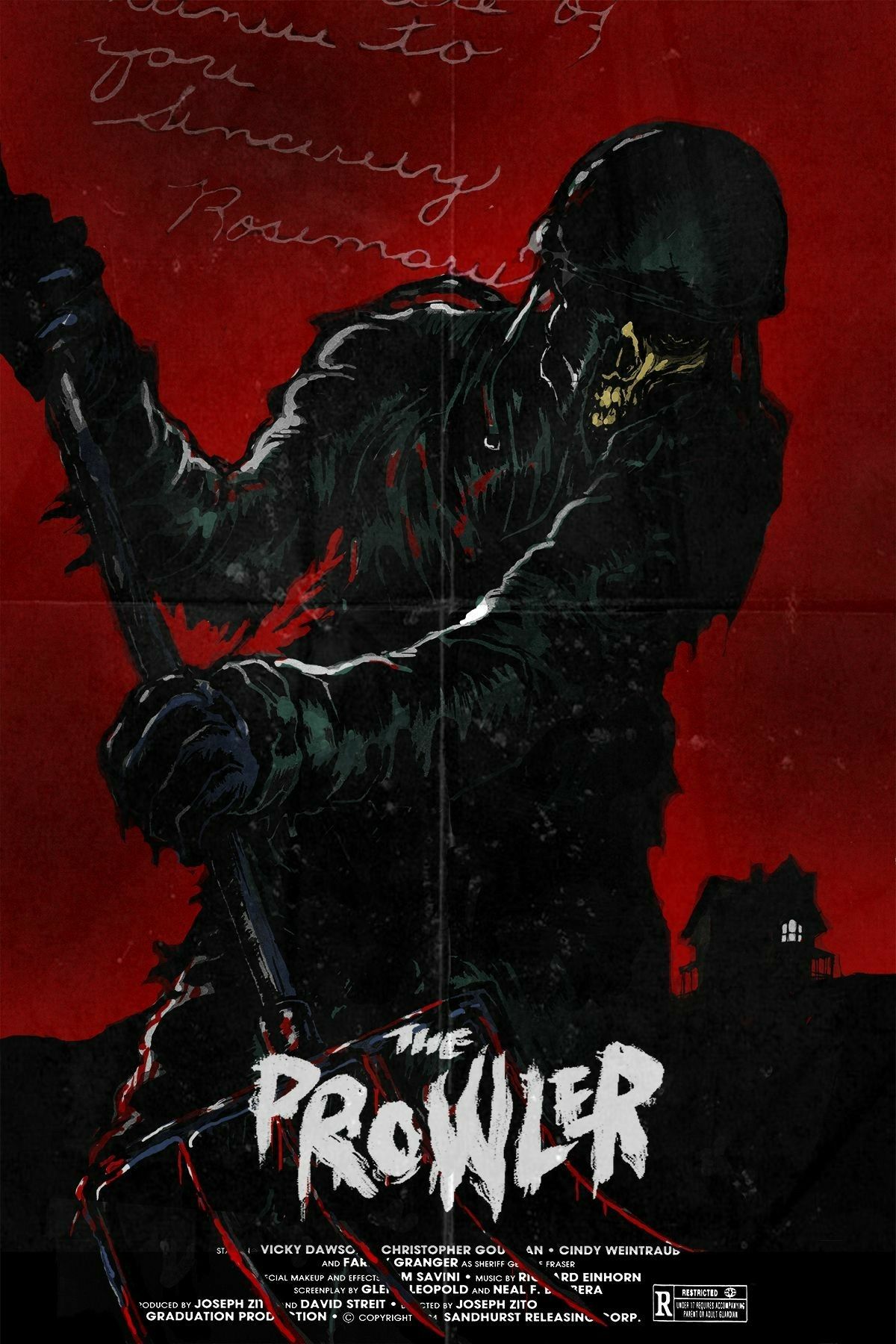

The Prowler begins rather curiously, a public service announcement welcoming home those brave American soldiers from the battle-torn trenches of the Second World War. Society is warned that it may take time for loved ones to re-adapt following a crash course in unspeakable horror, and when we suddenly cut to a narrated love letter in which a young girl named Rosemary informs her dear, departed soldier that she is no longer willing to wait for him, the typical slasher set-up is revealed, director Joseph Zito’s intentions laid bare. The movie’s killer inevitably exacts revenge on his ex and her new beau in a swift and brutal fashion, a precursor to a slew of anniversary killings 35 years in the making. It’s a somewhat fresh and intriguing opening that, purposely or otherwise, recalls the Uncle Sam ethics of a generation entrenched in ‘video nasty’ outrage.

For those who are unfamilar, the Italian giallo’s bastard offspring represented a generational shift in terms of what was acceptable as entertainment on British and American shores. Horror fans will be aware of the outrage that the sub-genre caused at its apotheosis and the almost puritanical reaction of parents worried about their children’s mental health and the terrifying degradation of a decenticised generation. At the turn of the 80s, just as the soon-to-be-infamous slasher was beginning to take off, an increase in highly publicised violent acts, including the assassination of former Beatles star John Lennon, led to a Motion Picture Association of America crackdown on creative violence.

In the UK, it was the ‘video nasty’ scandal that caught fire, a tabloid-driven crusade against independent filmmakers that saw 72 movies banned under the 1984 Video Recordings Act. Such widespread moral panic was pounced upon by a Conservative government looking to win favour during a time of economic and social upheaval, and for a while society closed the book on the kind of cynical violence that teenagers devoured in their droves, but that didn’t stop them from seeking out those fabled uncut versions.

Such movies took on an almost mythical status, whispered in playgrounds and rented under the counter in grubby VHS stores across the UK, establishments that were raided on a regular basis in what was a blatant attack on civil liberties. ‘Nasties’ such as the infamous Faces of Death, a ‘snuff’ movie that supposedly featured real-life acts of murder (in reality, most were staged, other scenes consisting of footage culled from accidents that had resulted in death), were absolutely shocking to audiences who’d been weaned on the Gothic and supernatural horror of yesteryear, particularly the slasher, which replaced the likes of Dracula and Frankenstein with suburban madmen that were much closer to home, channelling the energy of both real-life serial killers during the phenomenon’s peak years, and, something that is more closely reflected in The Prowler, the horrors of the Vietnam War, which thanks to advancements in the media were beamed into suburban households across the globe, giving everyday people access to atrocities that were mainly documented in print prior to World War 2.

I want you to be my date, Rose.

The Prowler

Some of those movies that were directly inspired by the Vietnam War and the nation’s serial killer boom, though no less controvertial and offensive to previous generations, have long-since been re-evaluated as innovative genre classics, Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, George A. Romero’s Dawn of the Dead and Bob Clark’s Black Christmas just a few filmic paraiahs that are now highly regarded among critics. But like any popular wave of innovation, such films would succumb to the marketing machine. If any movie is to blame for the abundance of cut and shut slashers that spewed out into the early 80s and beyond, it is John Carpenter’s equally lauded horror masterpiece Halloween, one of the rare violent horrors that was largely given its due upon release. But the real culprit is Sean S. Cunningham’s commercial eureka Friday the 13th, which was the first film on American shores to truly genericise what would soon become known as the Slasher.

During the early part of the 1980s, you couldn’t turn around without being confronted by yet another Friday the 13th clone looking to catch the public’s imagination on the same, money-spinning scale. Innovation and artistry would quickly give way to a very strict formula of vacuous stereotypes and masked killers, employing familiar settings, setups, and other endlessly regurgitated tropes. Even innovator Halloween was reduced to whoring itself to adhere to popular trends, Halloween II, a sequel that John Carpenter would later describe as “a horrible movie”, upping the graphic kills in an attempt to maintan Michael Myers’ commercial relevance.

Audiences would consume each violent offering like fast food as directors looked to outdo each other in the gore department, and while those earlier progenitors were in some ways a reflection of reality, slashers were seen as violence for the sake of it, many viewing the popular sub-genre as cause and motivation for potential real-life killers to set up shop. On the whole this was alarmist behaviour propogated by conservative values and media sensationalism, but there were stark instances of slasher related crimes that gave such opinions credence, especially in the UK.

In 1992, 16-year-old Suzanne Capper died from multiple organ failure arising from 80% burns after being deliberatley set on fire in Manchester, England. She had been kidnapped and tortured for seven days while rave music was played to her at maximum volume through headphones, specifically the track, “Hi, I’m Chucky (Wanna Play?)” by 150 Volts, which featured samples from Child’s Play. One of the perpetrators, 24 year-old Bernadette McNeilly, would begin each torture session with the phrase, “Chucky’s coming to play.” Director Tom Holland would later defend his creation, suggesting that a person could only be influenced in such a way if they were unstable to begin with, be that through nature, circumstance, or a combination of both. A year later, Child’s Play 3 was cited as an influence on the heinous murder of 2-year-old James Bulger at the hands of two 10-year-old boys, the details of which, much like the previous incident, are too disturbing to elaborate on. This would lead to a media campaign against ‘video nasties’, though UK police found no substantial direct influence other than a copy of the film at the house of the perpetrators and the use of paint.

In 1996, British serial killer and respected cinema manager Peter Howard Moore was sentenced to life in prison for the murder and mutilation of four young men. Dubbed the ‘Man in Black’, Moore was also found guilty of committing 39 sex attacks on men in North Wales and Merseyside over a 20-year period. When questioned by police, the deranged killer spoke of an accomplice named Jason. Only later did the authorities realise that he was referring to fictional serial killer Jason Voorhees from the Friday the 13th movies. It became clear that Moore was obsessed with the slasher, living out fantasies based on those movies, heinous acts that he admitted to doing “for fun”. The slasher may have been harmless fun for the most part, but for those with barely contained psychotic tendencies, they were a source of inspiration.

Despite being rough around the edges, The Prowler is certainly one of the more memorable, nastier efforts to come out of what fans lovingly refer to as the slasher’s golden age, and it’s all in the visuals. The film has a dreamy, almost woozy aesthetic that juxtaposes beautifully with sobering acts of explicit violence. It can be hypnotic at times. It also suffers from some pretty notable pacing issues, even with a scant running time of 89 minutes, but for pure, unabashed gore it is hard to top. In fact, if any slasher is deserving of the ‘video nasty’ label, it’s The Prowler, at least in its full, uncut form, which we’re now able to enjoy without fear of moral persecution. It’s right up there with Tony Maylam’s summer camp splatterfest The Burning and George Mihalka’s similarly dead-eyed My Bloody Valentine, movies which capture the era in all of its brutal glory. Of those movies, only The Burning made the video nasty grade, which speaks to the weirdly selective nature of the whole ordeal. All three were heavily cut for theatrical distribution in the US and Europe.

As with any government-imposed crusade, hypocrisy and petulance are par for the course, so The Burning wasn’t the only film to suffer such a fate. Trawling through some of those movies that did attain ‘video nasty’ infamy, it’s easy to deduce that much of the list was selected on a whim, the act of retribution more important than the details. Famously, the Friday the 13th series would later use working titles lifted from David Bowie songs in order to dodge the beady eye of the censors, who were known to target films based on titles alone. The fact that censorship proponent, Mary Whitehouse, who would label Sam Raimi’s The Evil Dead ‘the number one ‘video nasty’ after excerpts were screened in a special parliamentary session, later admitted to having never seen the film, speaks volumes. Ultimately, it was a case of the old guard fearing the new, an unwillingness to accept the changing times and tastes of the emerging generation. It’s a story as old as time.

Despite its cult status among genre fanatics, The Prowler is typical slasher fare. In fact, it’s rather underwhelming for the most part, even for a genre renown for being so rigidly formulaic, with characters who peruse a broken screenplay that plays out as if someone dropped the pages and hastily shuffled them back together. All the tropes are there ― an emotional trigger, a seemingly indomitable masked killer, a cast of archetypal teen victims and a softly lit, American-as-apple-pie final girl who will ultimately outwit our soon-to-be-unveiled menace ― but none of them are particularly remarkable. It’s textbook stuff that just happened to arrive during the sub-genre’s alluring peak. Not that slasher fans will care. Those who bask in the sub-genre’s dead-eyed cynicism aren’t looking for originality or even technical competence for the most part. The beauty is in the execution, quite literally, an area in which The Prowler excels and then some.

The Prowler, in its modern, uncut form, is unashamedly graphic. It delights in the icky details and relishes in its ability to push the visual boundaries. Despite a relatively low-output career, director Joseph Zito would leave quite the impression on the cult movie market, climbing aboard the Golan-Globus freight train to front exploitative Cannon classics Missing In Action and Invasion U.S.A., the latter causing quite the stir thanks to its reliance on gratuitous violence and casual xenophobia relating to real life events. The Prowler‘s eponymous killer, daubed in military garb and wielding a pitchfork and bayonet, is reminiscent of the kind of action character that Zito would later forge, with a few lock-and-load shots and a couple of firearms thrown in for good measure. The series of murders committed by his hand were some of the most brutal and ingenious ever witnessed back in 1981. Even by today’s standards they’re utterly convincing, more hands-on and tangible than anything achievable using CGI. At times it’s like watching a magician at work.

It may come as no surprise that the man responsible was practical effects icon Tom Savini, who used his experience as a former Vietnam War photographer to bring the horrors of conflict to the silver screen. Savini, who first came to prominence after bagging a Best Make-Up Effects nomination for his work on Romero’s Dawn of the Dead at the 7th annual Saturn Awards, would soon become synonymous with the slasher, working on such classics as Friday the 13th, The Burning, and Maniac, the latter he would describe as “The closest I have come to cold-blooded murder”, a fascinating insight into the morbid sense of reality that he aims for. Savini would also lend his inimitable skills to many non-slasher classics, working on such practical effects wonders as Creepshow and Day of the Dead, but even with such an astonishing resume, Savini would cite The Prowler as some of his best work, and he proves the absolute lifeblood of a movie that meanders through uneven spells like a POV presence begging to be let off the leash.

We haven’t had any trouble in that cottage for more than 30 years… now somebody has to start that damn thing over again.

Pat Kingsley

Legendary critics Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert, who were scathing detractors of the slasher phenomenom and its potential for societel harm, famously denounced Paramount for their commercial shenanigans surrounding the Friday the 13th series, the hugely popular Jason Voorhess becoming something of a poster boy for moral outrage. They would even go as far as giving out the names of the writer, director and producers of controvertial festive slasher Silent Night, Deadly Night on air as a form of retribution against money men with absolutely no moral fibre, but the slasher boom was also a postive window into the business for creatives who previously wouldn’t have stood a chance. As Savini would say about his time working on The Prowler back in 1981, “It was extremely exciting, an absolutely wonderful time because what it did was it accessed audiences in movie theaters all over the world for very low-budget films that could be made by people without a great deal of experience. And that’s a very, very tough thing to accomplish today.”

The Prowler, filmed in the ‘ghost town’ of Cape May, New Jersey, and shot with a grainy realism that had parent groups reaching for the flaming torches, is caked in so much blood that you’ll feel like you’ve been to an all-night Blade-style rave hosted by Lucio Fulci at his most shamelessly exhibitionist. Highlights include an ugly poolside throat slitting, a mind-blowingly authentic bayonet through the brain, an excruciatingly protracted incident with a pitchfork, delivered with a Psycho nod that lacks any semblance of subtlety, and an incredible exploding head via shotgun blast. Interestingly, it was often Savini himself inside the killer’s costume as he set about executing his gallery of cosmetic slaughter, which speaks to his dedication as an artist and his importance to this movie and the genre as a whole. Assistant director Peter Giuliano also chipped in for scenes in which our killer stalks the corridors of a college campus.

Shooting The Prowler‘s makeup effects was a long, laborious process, meaning that the schedule had to be built around them, and it shows. The film is mercifully short-lived and wastes little time on the Nouvelle hors d’oeuvres, slapping us in the face with a bloody T-bone, even if waiting times for some courses do threaten to turn us cold. Savini’s work on The Prowler was enough to bag him and Zito what was initially supposed to be the final Friday the 13th instalment. Friday the 13th Part IV: The Final Chapter, which many credit as the finest, most brutal entry, saw Savini return to the series for the first time since the original. This pleased him no end, despite the fact that his omission from Friday the 13th Parts 2 and 3 surely stuck in his craw. Not only had he given birth to Jason back in 1980, he would get to kill him for what was (supposed to be) the last time. Again, the movie would prove some of his finest work, and despite never reaching the heights of contemporaries such as the Oscar-winning Rick Baker, in horror circles he breathes the same air.

Despite featuring a killer who lacks the franchise-spinning lore of Jason Voorhees, an inferior cast, flawed structure and pacing, and, perhaps most crucially, a truly memorable final girl, The Prowler more than earns its reputation as one of the most infamous entries of the slasher’s golden age. Ultimately, it’s about the thrill and execution of the kill, and thanks to Savini’s dedication and morally questionable brand of magic, the film conjures the kind of startlingly authentic images that were rarely glimpsed in such a cheapskate sub-genre, incredible as the movie cost roughly $1,000,000. There’s obviously a ceiling when it comes to slasher fare, but if you’re in it for the practical effects, The Prowler is as good as it got back then, and it still looks amazing all these years later. When it comes to realistic depictions of death, Savini is a wizard of the grimmest variety.

Director: Joseph Zito

Screenplay: Neal Barbera &

Glenn Leopold

Cinematography: João Fernandes

Music: Richard Einhorn

Editing: Joel Goodman