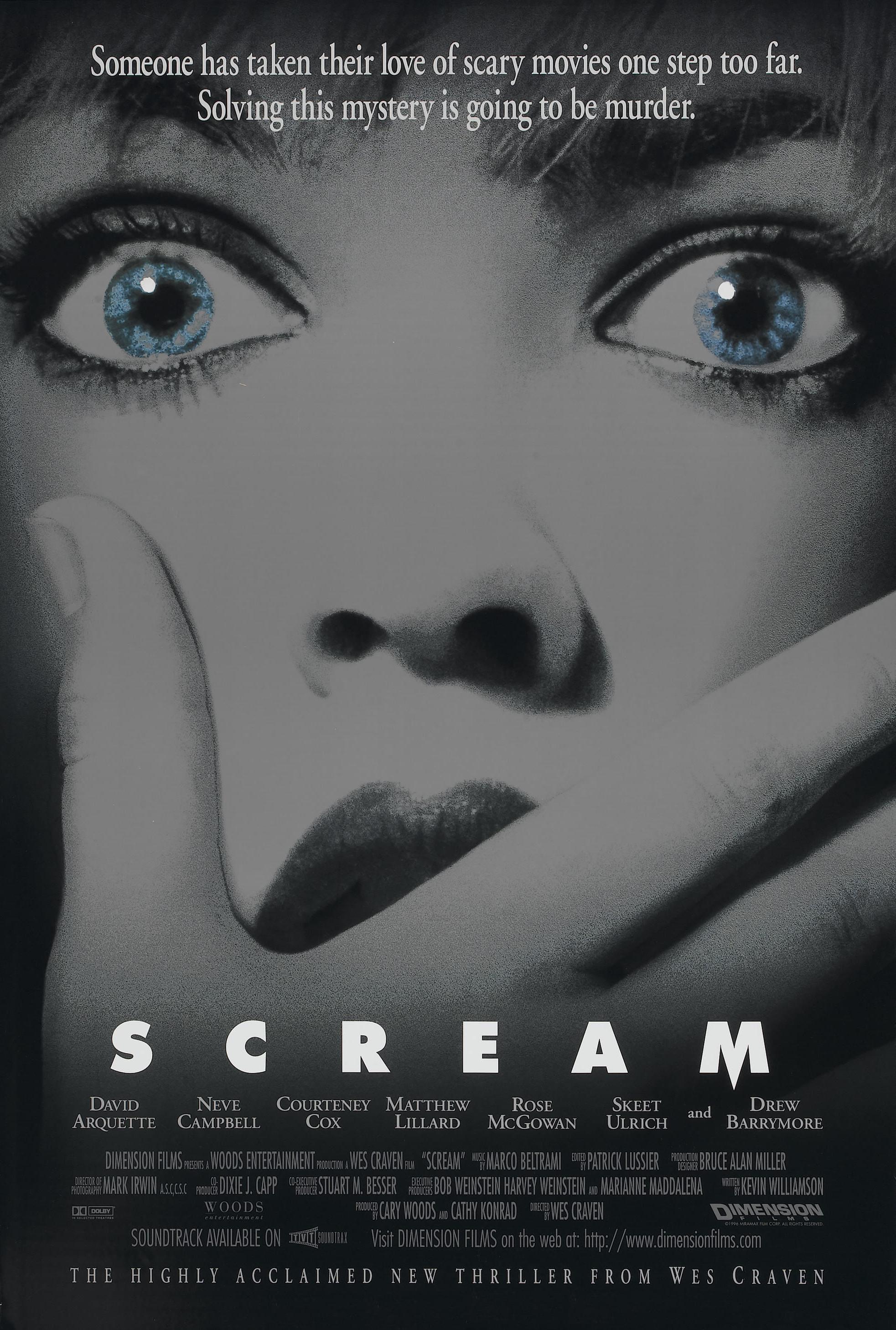

Wes Craven shapes a generation with a self-reflexive masterpiece

Every generation has a defining horror movie, and for millions of teenagers looking for scares in the mid-90s, Scream was that movie. Wes Craven’s second commercial eureka in as many decades wasn’t your average innovator, partly because of the state of the horror genre as a whole. Unlike previous decades, each boasting several horror movies that might be considered defining, the anemic early 90s was feeling the after-effects of the 80s home video boom as the oversaturated genre finally sputtered to a crawl. The sheer abundance of sub-par productions cashing-in on the emergence of VHS as a widely accessible format led to a huge drop in standards based on output alone.

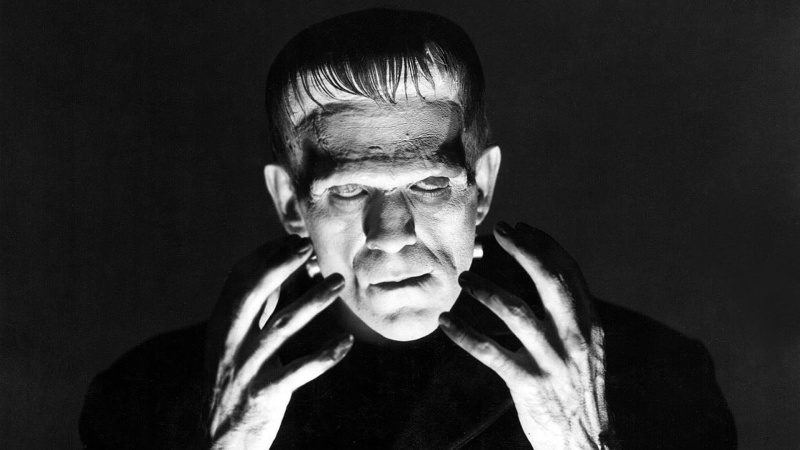

The 80s is still one of the most memorable decades for horror, boasting huge innovations in the field of practical effects and delivering such classics as The Shining, The Thing, The Evil Dead, The Fly and Wes Craven’s own A Nightmare on Elm Street. With films such as The Lost Boys, Fright Night and Near Dark, the decade would also reinvent the age-old vampire genre for post-modern sensibilities, but you were more likely to stumble upon something naff in an industry that was much more accessible to filmmakers of all abilities and intentions. That was a positive in some cases, allowing an open canvas for talented indie rookies who would go onto bigger things (think Peter Jackson), but audiences weaned on horror of previous decades couldn’t help but notice a certain degree of degradation.

There was also the subject of horror movie censorship. In a post-Satanic Panic era reignited by the inexhaustible Summer of Sam case and ex-Beatle John Lennon’s high-profile assassination, a backlash against onscreen violence reached almost puritanical levels during the mid 1980s. Horror would come of age during the 1970s, depictions of graphic rape, the torture and degradation of women, real-life animal cruelty and what at the time were very realistic portrayals of murder quickly replacing the fantastical monsters of yore. The 80s carried on those traditions. Leading the way was the hugely popular slasher sub-genre, innovators such as Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and John Carpenter’s Halloween replaced by sleazy Sean Cunningham style clones that established a very strict template, replacing novel characters with lazy stereotypes and establishing a series of universal tropes that audiences could easily identify with. Watching teenagers slaughtered by masked killers, punishment for unseemly indiscretions, became a generation’s favourite pastime, though not everyone was so enamoured with the lure of unprecedented onscreen violence.

Respected critics Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel were front and centre for society’s slasher backlash, even reading out the names of those behind 1984’s festive slasher Silent Night, Deadly Night, a film that was quickly pulled from theatres after initially outperforming Craven’s A Nightmare on Elm Street, the latter avoiding a similar backlash due to its superior craft and supernatural persuasion. Thanks in large part to the commercial desecration of a wholesome figure like Santa Claus (and I’m not referring to the Coca-Cola corporation), ’84 was the apotheosis for moral outrage, the straw that broke the reindeer’s back, but Ebert’s distaste was apparent from the very beginning. During his 1979 review of When a Stranger Calls, a film which employed the telephone motif later utilised in Scream, Ebert would say, “I think a lot of people have the wrong idea. They identify these films with earlier thrillers like Psycho or even a more recent film like Halloween, which we both liked. These films aren’t in the same category. These films hate women, and, unfortunately, the audiences that go to them don’t seem to like women much either… To sit there [in the theater] surrounded by people who are identifying, not with the victim but with the attacker, the killer – cheering these killers on, it’s a very scary experience.”

Another slasher icon, Friday the 13th‘s Jason Voorhees, would ultimately become Siskel and Ebert’s poster boy for moral outrage. So indignant was their dressing-down of the dubiously titled Friday the 13th Part IV: The Final Chapter that they helped trigger a tonal shift for the series and the slasher in general. The fact that horror’s ignominious descent into self-parody coincided with an explosion in the numbered sequel didn’t help affairs, and no one was safe, particularly Craven’s once genre-reviving Fred Krueger, who followed in Jason’s footsteps before usurping the character’s silly meta incarnation to become the genre’s new commercial king. Not only would Krueger jump the shark during the late 1980s, he’d devour the ocean and every last morsel of crappy merchandise within, becoming horror’s first bona fide rock star with a series of MTV tie-ins while indulging in the kind of perverse, youth-oriented marketing that saw New Line Cinema and its subsidiaries flog Krueger dolls and even Freddy brand pyjamas. For a character who stalked and murdered kids in their dreams, it was nothing short of unconscionable.

Never say “who’s there?” Don’t you watch scary movies? It’s a death wish. You might as well come out to investigate a strange noise or something.

Ghostface

A seemingly endless parade of sub-par and increasingly dubious franchise instalments would lay waste to the likes of Krueger, Jason, and even sub-genre inspiration Michael Myers by the early 90s. Fans had grown weary of the same old formula, sequels such as 1991’s Freddy’s Dead: The Final Nightmare and 1993’s Jason Goes to Hell: The Final Friday, New Line Cinema’s first fling with the Friday the 13th series having purchased the rights from Paramount with a view to producing a Freddy vs Jason crossover, both creative disasters that turned the majority of fans cold. Myers plundered on even further, Halloween’s cult of Thorn debacle leading the series down a similarly dismal path commercially. The slasher, and those emblematic figures who had become so hopelessly synonymous with it, were looking decidedly passé.

Enter Craven, who for the second time in a decade set out to breathe new life into a genre that was on life support and reaching for the off dial. Horror’s stock had arguably never been lower than it was in the early 90s, with only a smattering of classics for fans to cling to. Craven’s first attempt at reinvention came in the form of 1994’s New Nightmare, a precursor to Scream‘s meta shenanigans. A movie that revived the moribund Krueger by acknowledging him as a fictional creation while presenting us with a familiar re-imagining known as the Entity, the film blurred the lines between fiction and reality, series cast members appearing as both themselves and as their characters, the concept working as a multifaceted commentary on the series that preceded it. It also broached the kind of censorship mania that had transformed Robert Englund’s once wicked creation into a pantomime villain, or as Craven himself put it, “this whole idea of censorship and whether horror films are good or bad and whether they cause people to do things.” While the movie failed to make any serious commercial waves, it restored the integrity of one of horror’s most indomitable icons and sowed the seeds for the late-90s horror revival.

The catalyst for that revival was Scream, a film that took New Nightmare‘s self-reflexive fancies to new creative and commercial heights, leaving a new generation head over heels with both the slasher genre and horror in general. A Nightmare on Elm Street was similarly influential more than a decade prior, inspiring a whole host of imitators, but Scream was a transformative phenomenon, the horror equivalent of Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction in terms of capturing the cultural zeitgeist. Anyone old enough to have witnessed its release will attest to its popularity. The film raked in a whopping $173,000,000 dollars on a budget of only $15,000,000 for Dimension Films, whose days of wallowing in the bargain-basement Halloween doldrums were well and truly over. Critics were just as invigorated by Craven’s breath of fresh air. Even Roger Ebert was excited about the movie, writing, “As a film critic, I liked it. I liked the in-jokes and the self-aware characters. At the same time, I was aware of the incredible level of gore in this film. It is really violent. Is the violence defused by the ironic way the film uses it and comments on it? For me, it was.”

Like New Nightmare, at its core Scream acts as a commentary on the influential properties of onscreen violence, the very protestations that underscored the previous decade’s ‘video nasty’ furore, but censorship was around long before movies existed. Monarchies, religion, governments and various other forms of concentrated power have been ‘protecting people from themselves’ for centuries. In 1933, more than 25,000 books deemed offensive were burned in Germany, many more banned outright in the ensuing years based on ideological beliefs. In the 1950s, rock and roll was deemed the devil’s music, as was rock in the 1970s and 80s, around the same time that some horror movies were banned outright for their supposed influence on violence. In reality, the ‘video nasty’ hubbub was yet another in a long line of attacks on civil liberties, but where there is doubt there is justification, and as Scream‘s Billy Loomis, named after Donald Pleasence’s legendary character Dr Samuel Loomis from Halloween suggests, “Movies don’t create psychos. Movies make psychos more creative!”

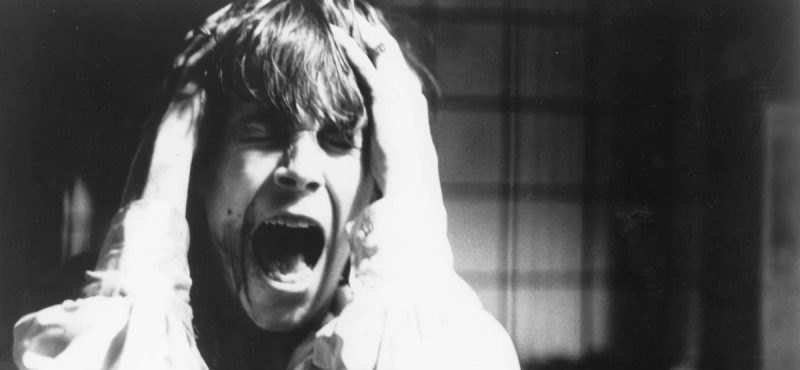

A fitting choice of words as Scream is one of the most creative and expertly executed horror movies of not only the 90s, but of any era — it’s that damn good. The film’s opening salvo, a beautifully orchestrated sequence that sets the self-reflexive tone while proving as violent, tense and genuinely frightening as anything that came before, is both an ironic deconstruction and a joyous celebration of the decade that preceded it. Every meticulous jump scare and revelation expertly dissects the horror movie rule book, reminding us exactly why we were sucked in in the first place. The scene in question shocks, thrills and subverts like very few openings in the genre’s history. Drew Barrymore’s Casey Becker is stalked by a nuisance caller beset on playing a game of ‘guess the movie’, her answers determining whether she lives or dies. A plethora of horror’s most iconic characters are central to the game in what is a breathless introduction to such a novel concept, one that, despite its heady meta overtones, is so user-friendly and relatable, presented as pure escapism of the highest order. The fact that Williamson pulls a Hitchcock during the scene’s closing moments, offing the movie’s biggest star before we’ve even had a chance to exhale, is the icing on a multi-tiered cake of endless delights.

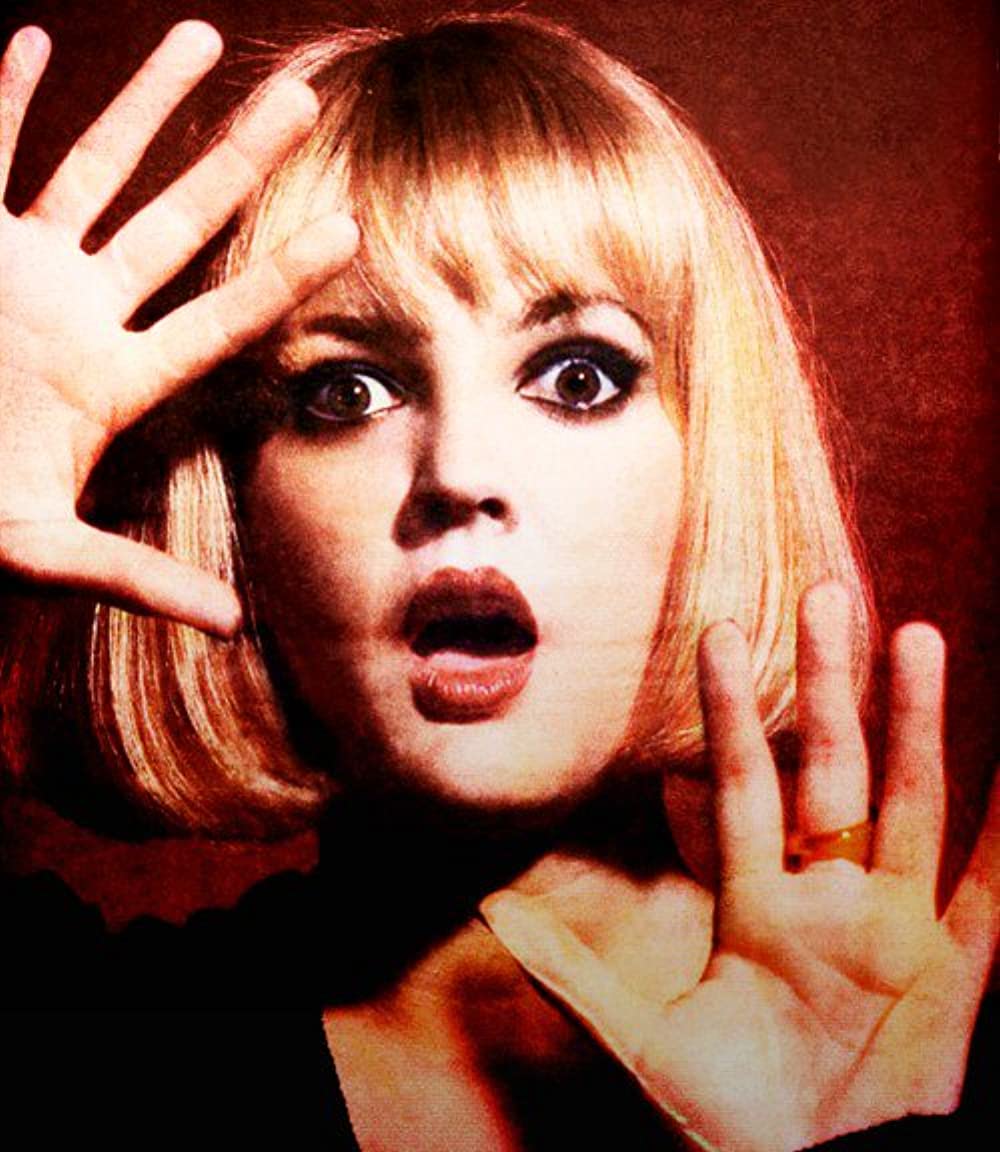

The fact that Scream elevated Barrymore’s career with little more than a cameo role, allowing her a second headliner stint after years on the sidelines, is further testament to the film’s potency, but also to Barrymore’s commercial savvy. Barrymore was originally set to play the role of protagonist Sidney Prescott but after reading the script had a change of heart. Alicia Silverstone of Clueless fame was originally considered for the part of Becker, but that changed after Barrymore approached Williamson and admitted, “The thing I love about this movie is the opening scene. I want to play Casey. That’s who I want to be.” Courtney Cox, a relatively new star just prior to the airing of Friends season 2, was equally beguiled by Williamson’s screenplay, actively seeking out the role of bitchy reporter and eventual heroine Gale Weathers, a character who would become a franchise mainstay. “I wrote a letter to Wes Craven,” Cox would recall. “I think I was always known as being so sweet, and I said, “I really can be a bitch!”

As well as Barrymore and Cox, Scream utilised a cast of relative unknowns who would all become instantly famous, and in a celebrity-obsessed era to its credit. David Arquette, a sibling to Patricia and Rosanna who would find romance with Cox both onscreen and off, would become a household name for a brief period, as would Skeet Ulrich, Charmed star and future Marilyn Manson muse Rose McGowan and the unknown quantity who would ultimately land the role of Sidney: scream queen and Jamie Lee Curtis of the 90s, Neve Campbell. “We were all at the beginning of our careers,” the actress would recall. “It was really new for all of us. At the time we could see there was talent around us and we knew the writing was good and we knew that people were having fun with the script and it felt very elevated, but to us it wasn’t a star cast. It became a star cast later.”

No, please don’t kill me, Mr. Ghostface, I wanna be in the sequel!

Tatum

As far as slashers go, Scream features one of the most memorable casts, as well as some of the most endearing characters, but the true star of the show comes in the form of the film’s inimitable villain, Ghostface, a near-parody of the masked killers who inspired the character that still proves as ominous, terrifying and visually iconic. A killer’s aesthetic is absolutely vital to the success of any horror franchise, and it doesn’t come easy. A gaudy, ineffective design is enough to sink any character along with the film that it represents. The most iconic masks are generally the product of sheer good fortune. Jason’s Hockey mask, stumbled upon during Friday the 13th Part 3‘s production, was initially a temporary aid provided by hockey fan and 3-D effects supervisor Martin Sadoff. John Carpenter went through a whole plethora of underwhelming designs before cutting the eyes out of a rubber William Shatner mask and spraying it white. Fred Krueger’s facial design was another happy accident, one first conceived by make-up artist David Miller as he played with a pizza while working on James Cameron’s Aliens, but the conception of Ghostface was a much more concerted effort.

First developed for Halloween novelty stores in the early 90s as part of Fun World’s “Fantastic Faces” collection, the mask, originally dubbed “The Peanut-Eyed Ghost”, was discovered inside a house by producer and one half of Craven/Maddalena Films, Marianne Maddalena, while out scouting for locations. Craven initially tasked practical effects magicians KNB Effects with producing a mask based on the design but eventually settled on the original after finally obtaining the rights. The KNB Effects version, which Craven wasn’t a fan of, still appears in scenes involving the murder of Casey Becker and Principal Himbry (former Arthur Fonzarelli Henry Winkler in a priceless against-type turn), the filming of which completed prior to the finalization of the deal between Fun World and Dimension Films (just imagine the money Fun World made off the back of that discovery!).

Bearing an uncanny resemblance to Edvard Munch’s expressionist masterpiece ‘The Scream’, our killer’s disguise boasts a perpetual expression of anguish, the character’s head cocking like a perplexed puppy as he stalks his self-assured prey. Not only is it symbolic of a generation warped by the extravagances of creative violence, it captures the almost childlike inquisitiveness and lack of empathy found in the likes of Jason Voorhees and Michael Myers. The character also boasts a similar omnipotence, possessing the ability to be everywhere at once, but anyone who’s had the pleasure of experiencing Scream will know that this isn’t the result of the kind of quasi-supernatural abilities found in his peers. Ghostface is a truly post-modern creation; frenetic, vulnerable, distinctly human. He’s a mortal projection of man’s fascination with gallows human and the grossly immoral. He’s Wes Craven.

Kevin Williamson’s stock would soar after his game-changing screenplay, the former TV writer delivering a series of like-for-like vehicles in the wake of Scream‘s success, but Craven is just as important to the movie’s impact and legacy. Not only had he explored themes in New Nightmare that Williamson expanded upon, his craft and ingenuity keep us on our toes in a film that otherwise plays out like a self-fulfilling prophecy. We know what should happen, but in a purely meta environment Craven’s an expert at raising doubts from a directorial perspective. He also adds a sense of fun to a concept that could easily have proven too cerebral. The film is excessively violent, featuring a graphic disembowelment and a brutal hanging before the credits have even rolled. In a lesser movie, the image of Barrymore’s Casey Becker hanging from a tree like a skinned animal would have left a bad taste in the mouth, but the movie never resorts to such dead-eyed cynicism. Through sheer, childlike energy and enthusiasm for the genre, Craven crafts a purely joyful experience, orchestrating events like a kid in a candy store. He even pops up in a pseudo-cameo as a school janitor named Fred who bears a striking resemblance to his most famous razor-fingered creation, clearly relishing in the transparencies of the whole concept. In terms of understanding the genre and its audience, Scream may be Craven’s greatest ever achievement. It is an absolutely masterful turn from one of horror’s true innovators.

Not only did Scream appeal to a new generation of horror fans, it delighted fans of old with its cute genre nods and delicious sense of self-mocking, playing out like a horror movie encyclopedia with a meticulous index. A brief glance at Scream might suggest that there’s nothing new at play. It delivers the same tropes and stereotypes, featuring a cast of beautiful teens, familiar high school and suburban settings, a marquee villain, a kill count to die for, and countless other conventions that audiences have witnessed a thousand times before, but look closer. There may be a sense of déjà vu at play but that is precisely the point. Not only does Williamson’s similarly transformative screenplay deconstruct horror movies, it deconstructs itself, foreshadowing each reveal so transparently that you know exactly what’s coming, even down to the finale’s inevitable ‘one final scare’. Existing horror characters are referenced through cameos, dialogue and narrative developments, even determining the plot at times. The film’s characters provide what’s almost a running commentary, explaining what will happen moments before it does, the irony being that they’re still prone to error, doomed to live out the painfully inevitable. Quoting various fictional villains, Scream‘s copycat killers are determined to direct their own real-life slasher right down to the finest detail, using corn syrup as a visual aid for their convoluted plot — the same used for pig’s blood in Carrie. Ultimately, the film works within a familiar construct in order to subvert it.

The characters in Scream know they’re in a horror movie, and having been exposed to so many they know what to do in order to survive — at least in theory. As the students of Woodsboro are picked off by a mysterious masked killer on the anniversary of a former resident’s murder, a very familiar pattern emerges, but it’s our ability to identify with the finer details that proves so much fun, our participatory role as smug insiders that sets Scream apart as a truly unique experience. The film reinvigorates tropes that had become dull and tedious. As the rules are explained they very quickly become a realisation. People who drink and have sex inexorably fall victim, and there are things one should never say if you expect to survive proceedings. ‘I’ll be right back,’ is a definite no-no, while venturing to the garage for illegal libations is a sure-fire way to end up dead. These are the kind of risible moments that have left horror fans screaming at theatre screens for decades. Why rest next to a seemingly dead body instead of finishing the job?! Why split up when you can stick together and have strength in numbers? Why go outside to investigate a strange noise or run stumbling into the woods in a pair of high heels? It all seems so obvious.

The police are always off track with this shit! If they’d watch Prom Night, they’d save time! There’s a formula to it. A very simple formula!

Randy

The cast of Scream are much more sophisticated than the legions of braindead victims that preceded them. They’re well-schooled in a genre that has become risibly predictable, blasé about our killer’s typically hegemonic powers, supercilious to the whole ordeal, and mostly to their detriment. When Rose McGowan’s Tatum is cornered by an assailant who she assumes is playing a prank, she snarkily begs him to spare her life so she can star in the sequel, but when she senselessly attempts to crawl through a cat flap on a remote-controlled garage door, she becomes the crudely squished victim of her own conceit. When final girl Sidney Prescott, the movie’s Snow White virgin, is asked for her opinion on scary movies, she dismisses them as insulting, telling our killer, “What’s the point? They’re all the same. Some stupid killer stalking a some big-breasted girl who can’t act who’s always running up the stairs when she should be running out the front door.” Later in the movie, pursued by that same killer, guess where she ends up running… Then there’s Woodsboro’s resident geek Randy, a part-time video store clerk who spells out the rules for survival in no uncertain terms before inevitably running into trouble. Later, after avoiding death by the skin of his teeth, the character says, “I never thought I’d be so happy to be a virgin”. In case you didn’t know, virgins generally don’t die in slasher movies.

Scream‘s legacy and influence on the horror genre during the late 90s and beyond cannot be underestimated. Like Halloween before it, it forged an era that it would ultimately transcend, becoming a cultural phenomenon that was often imitated but never bettered. Inevitably, the film would inspire a mostly stellar franchise, Scream 2, a movie which poked fun at the tropes inherent in sequels and the many symptoms of sequelitis, feeling almost necessary. Kevin Williamson would recycle the Scream formula numerous times before the decade was up, movies such as I Know What You Did Last Summer, The Faculty and Teaching Mrs. Tingle treading similar ground but lacking the acerbic bite, descending into the very formula that inspired the whole Scream concept. In the ultimate irony, Williamson was even the uncredited driving force behind Scream derivative Halloween: H20, turning original slasher template Michael Myers, a character at odds with the decade’s hip, self-aware style, into a veritable Ghostface clone. If nothing else, it spoke to the power of the character and the movie that forged him.

Today, meta horror that wears self-deconstruction on its sleeve is everywhere, has grown even more adventurous and self-reflexive, but it explores land that was founded by Craven and Williamson. Self-aware horror existed long before Scream, Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom being a case in point, but never was it delivered with such scholastic precision in such an accessible and universal fashion. It placed a microscope on a genre that was experiencing severe burnout, reigniting the flames of audiences who had been turned off by tepid horror sequels, censor-appeasing silliness and franchise stagnation. It was invigorating, dynamic, years ahead of its time, and remains one of the most prescient and important horror movies in history.

The same can be said of the late Wes Craven, who had a knack for rescuing horror from out in the cold, who always seemed to probe further, bringing unique insights and refreshing twists to the genre in the most infectious way. He had a few stumbles along the way, a few executive-led disasters and over-zealous misfires, but he was never afraid to take risks, to venture where others dare not, and his finest movies would make even the most distinguished horror CV. I sometimes wonder what he would be doing if he was alive today, because filmmakers like him always seem to have something revolutionary up their sleeve, a concept or a philosophy or a character to ignite the imaginations of a new generation. The world is a sadder place without him.

Director: Wes Craven

Screenplay: Kevin Williamson

Music: Marco Beltrami

Cinematography: Mark Irwin

Editing: Patrick Lussier